Editorial Note: As I typed up my sixth page of material on Rocky II, intended to be but part of the preface for my Rocky IV review, I realized I was insane. That was the only explanation for writing a ‘preface’ that was as long as the review itself. In any case, please feel free to jump over to the second page of this review by clicking on the link provided at the bottom of this page.

In 1976 a truly storybook show biz story came along. Its central character was one Sylvester Stallone, a largely unknown actor who had been pursuing a film career without overmuch success. Already past the age when most actors have been discovered by the public, he decides to take a long shot chance and write a screenplay. The script is about a two-bit and slightly over-the-hill Philadelphia boxer who never made of his talents what he might have, but who out of nowhere receives one last, improbable shot at the big time.

The script becomes a hot property, and the all but literally starving Stallone is offered a large amount of money for the rights. However, he steadfastly refuses to sell the screenplay unless he himself is allowed to play the main character. It’s a meaty role, and the producers know they could attract a big star with it. They offer more money, but the actor remains adamant. In the end, the power of the script wins out. The movie is put into production, albeit with a rather more conservative budget than it might otherwise have gotten. Eager to make the film, Stallone basically sells the script for a song.

The film has, in contrast to many of the more dour films of that decade, a triumphant tone. For the more cynically minded, however, there is a saving grace. In the end, the boxer loses the big fight, yet in a way that vindicates him beyond any of his earlier dreams. It’s a fairy tale ending, but the fancifulness is restrained by a soupcon of reality.

The end of the real life story, meanwhile, proves even more upbeat. The movie is not only a smash hit, but a bonafide cultural event. Stallone finds himself nominated for both the Best Actor and Best Screenplay Oscars. Much like his fictional counterpart, he loses, yet is still vindicated beyond his wildest dreams. While Stallone takes neither of statuettes he was nominated for, the film itself wins both Best Director (John G. Avildsen) and Best Picture, beating such instant classics as Network, All the President’s Men and Taxi Driver. Moreover, while he would never again receive such critical validation, Stallone would go on to become one of the most famous and well-paid movie stars in the world.

However, in the shorter term things don’t go as planned. Stallone strove to separate himself from the punch-drunk boxer who otherwise paralleled him in so many ways, while working to establish an intellectual image that he would vainly (in both meanings of the word) attempt to sell to the public. In pursuance of this, Stallone took a year off from filmmaking before coming back with what was patently intended to be an Important Film.

His follow-up was F.I.S.T. (1978), a movie set against the often corrupt Teamster union agitations of the 1930s. The project fails at the box office, however. So does his next picture, Paradise Alley, a seriocomic period wrestling movie that sought to josh (yet hopefully replicate) his star-making role in Rocky. The film was a pivotal one for Stallone, in that it was here that he first failed at things he would continue to fail at for decades to come; successfully directing a movie and doing comedy.

With only one well-received film under his belt, and his career quickly losing steam, Stallone conservatively returned to the role that made him a star. Taking his best, if easiest, shot at directing a film, he made the solid if unspectacular sequel Rocky II (1979). The film casts Rocky back in the role of the underdog, as he discovers that his (largely moral) triumph in the first movie hasn’t magically changed his life for the better. Again tracking with his alter ego’s experiences, Rocky learns that success in one thing doesn’t necessarily translate to success in others. As with Stallone himself, the film finds Rocky in imminent danger of returning to his former has-been status.

Stallone again wrote the screenplay, and the film contained many touching character moments of the sort that had elevated the first film into being more than the 100th boxing programmer. The sweet love story between the awkward and socially inept duo of Rocky and Adrian, especially, continued to enchant audiences.

However, the series was already starting to become more cartoonish. Desperately needing another hit, and with only one real direction for a sequel to go in (at least a sequel designed to make money), Stallone acquiesced and gave the audience what they wanted. Reality be damned. This time, underdog Rocky, against all logic, wins the Big Fight. In return, the audiences returned the favor, and the film was a major success.

His career rejuvenated by this second smash hit, Stallone once more sought to prove that he wasn’t a one trick pony. He next played a cop in the violent action thriller Nighthawks, and mixed up his image with a beard and by wearing glasses. The film is fairly decent, and garners similarly solid critical response (albeit mostly for Rutger Hauer’s star-making role as the film’s psychopathic villain). The box office results, however, are more mixed.

The same year also saw Stallone take part in the ensemble WWII POW soccer epic Victory, opposite Michael Caine and Max von Sydow. Although directed by John Huston, boasting a big-name cast (including real life soccer sensation Pelé), and being another attempt at a sports-themed movie with an outsized triumphant ending, Victory also failed to draw large audiences.

His career once more in danger of stuttering, Stallone perhaps reluctantly returned to the well for another dip with Rocky III (1982). Again writing and directing the film, Stallone had little choice but to push the series further in the increasingly ridiculous, outlandish direction that was popular with film audiences in the ’80s.

Now relying on the death of a beloved supporting character to keep the audience’s emotions engaged, the film also replaced Rocky’s boxing opponent. Instead of the man he displaced as the Champ, the classy, urbane Muhammad Ali-analogue Apollo Creed, the film found Rocky himself faced with a hungry, younger, upcoming boxer. Rocky’s foe in this chapter would be the comically exaggerated Clubber Lange. “You can’t beat ‘im, Rock!” Rocky’s loveable old manager Mickey famously exclaimed. “He’s a wrecking machine!“

Clubber Lange was such an absurdly cartoonish thug that he was barely short of being a James Bond henchman. This is the role that introduced Mr. T to stardom, although it wasn’t until the following year, as a member of TV’s The A-Team, that Mr. T’s immortality was ensured.

Rocky III early on signals that the series’ previous attempts at kitchen sink realism were completely out the window. One sequence revolves around a charity match starring Rocky, a beefy but (in the person of Stallone) hardly gigantic individual, facing a veritable goliath. The latter was played by Hulk Hogan, and brought him for the first time to the attention of non-wrestling fans. Hogan and Mr. T actually started hanging out, and T even had a brief stint as a wrestler. The pair was temporarily popular enough that they co-hosted Saturday Night Live together.

Although critics suspected that the Rocky series would start losing box office juice with this more ludicrous chapter, it again proved hugely profitable. However, some of this success was undoubtedly due to the movie’s phenomenally popular theme song, Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger.” The constant radio and TV airplay captured by the song and the band’s music video kept the film in the public’s mind and proved a spectacularly fecund source of free publicity.

And then, with one smash hit already under his belt, that same year finally saw Stallone break the Rocky curse. That occurred with the release of a small action film entitled First Blood. In the role of John Rambo, Stallone finally had a successful character who wasn’t the increasingly aging and ludicrous Rocky Balboa.

This second success occurred at just the right time, though. While First Blood finally proved that audiences would accept him as something other than a one-trick pony, it would sadly only be as a two-trick pony. The paired double smash hits of Rocky III and First Blood pushed his star about as high as it could go, but they were followed by the one of the worst stretches in Stallone’s career.

The first stumble came as Stallone again attempted to establish himself as a director, this time by helming a film that he didn’t star in. Unfortunately, this project proved to be the hilariously inept musical Staying Alive (1983), which was moreover a failed sequel to one of the most critically beloved films of the prior decade, Saturday Night Fever. As much of the pre-release publicity centered on Stallone helping John Travolta to develop an exercise program to build himself up into a megabuff mini-Stallone, it’s perhaps unsurprising that the film was as horrible as it ultimately proved to be. If not for my doing Rocky IV for this roundtable, Staying Alive easily could have been my subject.*

[*Actually, you can sort of see where they were going with this idea. The original Rocky has a lot in common with Saturday Night Fever. Both films centered on a somewhat dim lower class protagonist, who yet yearned for something better. Each closely observed the protagonist’s relationship with the parochial, heavily Italian neighborhood in which he’s lived his entire life. Sadly, though, the Stallone who signed on to Staying Alive was the Stallone of Rocky III & Rambo: First Blood Part 2, not the one who wrote the original Rocky. Staying Alive boasts all the worst aspects of the later Rocky films, without exhibiting any of the saving graces that remained to that series.]

Staying Alive proved a critical and financial disaster. It certainly put paid to Stallone’s directorial career. Except for Rocky IV, he would not helm another film for 23 years. (And that was the recent Rocky Balboa.) Licking his wounds from that debacle, and with his star in danger of being eclipsed by fellow action hulk Arnold Schwarzenegger, Stallone once more attempted to experiment. The result was the truly dreadful ‘comedy’ Rhinestone (1984), a Pygmalion tale in which country singer Dolly Parton (who quite simply blows Stallone off the screen) tries to make a vocalist out of New Yawk cab driver Stallone.

With his career nearly dead, Stallone again retrenched with the comically titled Rambo: First Blood Part 2 (1985) and our subject for today, the same year’s Rocky IV. This was his last gasp of superstardom, as he otherwise continued to churn out increasing awful and financially unsuccessful films, many of them outright bombs.

Rambo III (1988) was his last huge hit, although he would finally achieve some level of non-Rambo and Rocky box office success with later films like Cliffhanger and Demolition Man (both 1993). However, those occasional minor successes could not make up for a continuing series of turkeys such as Cobra (1986), Over the Top (1987), Oscar (1991), Stop! Or My Mother Will Shoot (1992), The Specialist (1994), Judge Dredd (1995), Assassins (1995), Get Carter (2000) and Driven (2001). Most ominously, perhaps, 1990 saw Rocky V fail at the box office, proving that Stallone’s workhorse roles could no longer keep his career afloat.

Eventually, Stallone’s films started going direct to video—remember titles like D-Tox? Avenging Angelo? Shade?—as he only occasionally resurfaced in the public eye with films like Cop Land (1997) and 2006’s well reviewed sixth (!) Rocky picture, Rocky Balboa. Even for that film, however, audiences were largely absent, and the now 60 plus-year-old Stallone’s last slim hope for another hit movie is (should it actually get made) the forthcoming Rambo IV: Pearl of the Cobra.

*****

Time for a confession. While I have seen the first four Rocky movies, I saw them during their initial theatrical runs, and haven’t viewed them since. In other words, I last saw the subject of this review about 22 years ago. So let’s hope it isn’t better than I remember, because otherwise I’ve screwed the pooch here.

Moreover, in that this is a bad sequels roundtable, I guess it behooves me to actually watch the movies that precede Rocky IV. In retrospect, perhaps I should have picked something that didn’t require me to watch four films. Ah, well. In any case, my thoughts on the series’ drift, as found above, were just my riffs on the films as I remember them these decades later. So let’s at least give each of the previous films a quick run down.

*****

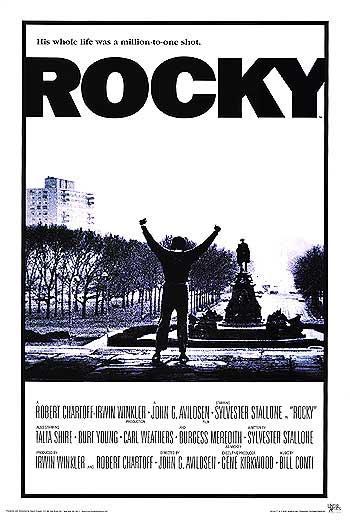

Rocky opens with the title scrolling across a black background and accompanied by a trumpeting fanfare. This will prove an ironic counterpoint to the bulk of the film itself, which really is largely a kitchen sink drama. We open on a prize fight taking place in a small, grubby gymnasium. Rocky Balboa is one of the contestants, and the action is largely desultory. Although a professional fight, it’s obviously not a highly ranked one. Rocky looks uninspired and takes a pretty good beating, at least until his opponent fouls him. Rocky reacts with a burst of irate energy, and quickly beats the guy down. In the dressing room, as the boxers kick back with cigarettes and beers, the purse is divided. As the winner, Rocky collects the larger sum, about forty dollars.

Rocky’s chance at greatness arrives, unbeknownst to him, when the contender in an upcoming heavyweight championship match is forced to drop out. This leaves the current title holder, the brash and erudite Apollo Creed (Carl Weathers), with a hugely publicized event scheduled for the upcoming July 4th Bicentennial, but no opponent.

After being ducked by all the other ranked contenders, Creed has a brilliant idea. He’ll celebrate America’s greatness by offering a local unknown a shot at the championship. Moreover, his opponent will be white. (The film is thus nicely cynical about racial issues, without beating the subject to death.) In the end, Creed, who basically views the whole thing as a lark, picks Rocky pretty much solely for his self-given nickname, the Italian Stallion. This despite his manager’s concerns about his fighting a southpaw, which Rocky is.

Playing out at just about two hours, the amazing thing about Rocky is, first, how little the boxing has to do with things, and second, how naturalistic it is. The latter is especially weird, because in many ways the film is a veritable cliché fest, emulating every boxing picture Hollywood had made since the ’30s. Rocky himself is definitely an old-style palooka, a kind-hearted but rather dense mug. He even walks like a movie boxer, constantly rolling his shoulders and tossing jabs around. However, after a while this actually begins working. You start to believe in Rocky (which, it must be said, is a credit to Stallone), perhaps as a guy who learned to be a boxer from watching old movies.

Growing old for the penny ante fights he can still get, Rocky’s day job is as an enforcer for a local small time loan shark (who still is the most glamorous guy seen in the neighborhood). The problem is that Rocky isn’t very good at his job, as his heart isn’t in hurting people. Even so, his occupation draws the scorn of Mickey (Burgess Meredith, all wrinkles and a painfully raspy voice), the aged former boxer who runs the gym Rocky trains at. Irate to find that he has lost his locker privileges, Rocky soon is subjected to a tongue lashing from Mickey, who berates him for wasting his very real fighting talent.

The core of the film, however, is Rocky’s pursuit of Adrian, the painfully shy sister of his mean and nearly retarded-seeming friend Paulie. It’s this relationship that really buoys the film and makes it work. Living a grim existence built around a crappy job and a home life that solely involves taking care of her brutish and verbally abusive brother, Adrian reacts to Rocky’s halting attentions with something approaching panic, so unused is she to simple affection and respect.

The scene where Adrian allows Rocky to seduce her is terrific, as she finally overcomes her fears that he’ll do something to hurt her. (This is cannily followed by a parallel scene in which Rocky is first offered the Creed fight. Similarly afraid that nothing good can come of such a bewildering stroke of luck, Rocky’s initial reaction is to turn the fight down.)

Anchored by a completely believable performance by Talia Shire, this relationship achieves many things. First, it shows that for all his fears, Rocky hasn’t given up on improving his life. Patently no Lothario, Rocky obviously sees something in Adrian that nobody else does, and is dogged but sweet in pursuing her. Their first date at a closed-up skating rink, as he attempts to use his sense of humor to get past her emotional barriers, is exceedingly well observed.

Only after we spend the bulk of the movie getting to know Rocky and his world does the boxing plot really come into play. The film’s famous training montage, set to the soaring, Oscar-nominated song “Gonna Fly Now,” takes place after the movie is three fourths over with. One thing that really makes the sequence pop, by the way, is the paucity of music up to this point. Unlike today’s movies (and the later Rocky entries), this picture isn’t a series of music video moments. Much of the film is sans music entirely, and the rest uses music but sparingly. As a result, when the theme song bursts loudly out of nowhere after an hour and a half of comparative silence, it’s genuinely exciting.

It’s a rousing, triumphal scene, but quickly followed by Rocky’s coming to realize that Creed is just out of his league, and that he can’t possible beat the man. In a nice touch, when he confesses this to Adrian, she doesn’t attempt to convince him otherwise, but simply asks, “What’ll we do?” She learns that his real goal is simply to go the distance in the fight, something that no one else has ever done before when fighting Creed. Even if he can’t win the fight, he wants to prove that he isn’t beaten, either. He wants to show that he can take everything life can throw at him, and still remain standing.

When the fight finally does occur, it is a bit oversized, but not in a ridiculous way. Rocky is big and well-muscled, but Stallone isn’t as grotesquely ripped as he’d get later in the series. The action is fairly restrained, and the punches aren’t the sort of lethally superhuman, cannon-like blows that we see Rocky and his opponents trade and absorb for ever-increasing lengths of time in the later entries.

The fight was partly inspired by a bout between Muhammad Ali and white boxer Chuck Wepner. Like Creed here, Ali didn’t take the fight seriously, and for the first and last time as the world champion, found himself ingloriously knocked onto his ass. After that, Ali went to town, and unlike Rocky, Wepner failed to go the distance, being knocked out in the 15th round.

Here, however, the final bell finds the two battered, exhausted fighters hanging off one another. “There won’t be a rematch,” Apollo gasps. “I don’t want one,” Rocky replies. Rocky has achieved his moral victory, and calling out for Adrian (he has been half blinded by his swollen eyelids), he embraces her and savors his greatest moment, captured forever in a freeze-frame.

Rocky succeeds best during its more painful moments. Rocky fears that he is, in fact, doomed to become a bum. Adrian’s initial inability to trust Rocky’s evident feelings for her I’ve already mentioned, but it’s really one of the best things the film offers. (Equally credible, however, is her transformation after taking the chance. She’s like that once ramshackle Christmas tree in A Charlie Brown Christmas, blooming after it receives its first taste of love.)

And then there’s gym owner Mickey. Meredith was nominated for a Best Supporting Oscar here, but again, his role is fairly small. Mickey’s central scene is when, literally hat in hand, he shows up at Rocky’s apartment, offering to train him for the big fight. Mickey’s naked hunger for his own last chance at the big time is palpable, as is his confused, bitter awareness that he might well have screwed himself with his recent rebuking of the boxer. And sure enough, Rocky treats him with icy and clearly disinterested politeness, clearly resenting the years of derision he’s received from the old man. Unable to paper over this chasm with unconvincing stabs at bonhomie, Mickey eventually shuffles out of the apartment, defeated.

Only when Mickey is out of sight does an enraged, shouting Rocky let go, spewing forth at last an angry litany of complaints about his life. (In a way, this parallels John Rambo’s big speech at the end of First Blood, although here it seems more honest.) Yet once Rocky has finally purged himself of this poison, he immediately runs outside and takes Mickey up on his offer, clearly as much for Mickey’s sake as for his own. It’s moments like this that successfully sell Balboa, whatever his flaws and limitations, as a truly big-hearted person.

Cinema buffs might well sniff at Rocky beating out Network and especially Taxi Driver for that Best Picture Oscar. Still, there no doubt this is an iconic piece of work, and with a very real integrity. Sadly, though, Rocky and Creed would both prove wrong. There would, in fact, be a rematch, and the loser would be the series’ credibility.

*****

In my Jaws II review, I listed the Elements Indicative of a First Sequel:

o A discernible slip in quality from the parent film is already evident. A superlative film is followed by a pedestrian one.

o A significant number of people involved in crafting the original film are conspicuous by their absence.

o In areas in which its predecessor was accomplished, the follow-up will range from competent to ludicrous.

o Various plot devices and stylistic elements from the earlier movie are simply rehashed, only with much less verve, panache and, obviously, originality.

o Other aspects are souped up, often counterproductively, to compensate for this fact. Material introduced to emulate other contemporary films proves inappropriate.

o The unlikeliness of the initial picture’s premise will be substantially magnified by its reoccurrence here. Suspension of disbelief is therefore less readily granted.

o Some films are designed to have an ‘open ending,’ allowing for the smooth transition to a sequel. Others, such as Jaws, are not. This generally results in a greater artificiality and pronounced awkwardness in the second film’s proceedings.

o There’s little apparent reason, other than the lure of box office lucre, to justify this film’s existence.

o The result is a film that’s watchable, but mediocre and often flaccid.

These tenets don’t uniformly hold true for Rocky II, but most of them do. The most pertinent exception, however (and definitely in contrast to Jaws II), is that there is an actual, arguably legitimate plot rationale for the second Rocky film. This, aside from the obvious hope of making a ton of box office lucre, was to provide fans of the first film with the full-fledged, flat out fairy tale ending the initial movie forewent.

The pivotal moment of the first film is when Rocky comes to grip with the fact that he can’t possibly beat the world champion. In lieu of this, his goal becomes to “go the distance,” to take all the champ can dish out and walk from the ring under his own steam. This cannily lent the film a touch of realism, while still allowing the audience to experience a feel-good ending.

However, the hallowed ’70s, the second golden age of Hollywood filmmaking, was drawing to an end. Coming in its place was an era of sequels and outsized blockbusters. The continued box office success of the Rocky films was no doubt due to the fact that the series moved from a small scale ’70s sensibility (as exemplified by the first film’s less than fully triumphant ending) to a more cartoonish and overblown ’80s tone.

Rocky clearly wasn’t made with a sequel in mind. In fact, having Apollo Creed actually exclaim that there wouldn’t be a rematch, followed by Rocky’s reply of “I don’t want one,” seemed designed to rule one out. (Of course, nobody knew how much money Rocky would make, either.) Yet with both hungry studio coffers and Stallone’s faltering career demanding a follow-up, the only possible internal justification for such a thing was to be The One Where Rocky Wins. This arguably cheapens the first film, and, in fact, I would so argue. However, quite apparently legions of ticket buyers didn’t care overmuch. Certainly neither Universal Studios or Stallone himself was complaining.

Still and all, if Stallone was going to prostitute himself and his greatest creation in order to rejuvenate his career, he was going to have as much control as possible. He not only wrote and starred in this chapter, as he did the first time around, but took over the directorial reigns from John Avildsen. (One must wonder if Stallone, nominated for two Oscars for Rocky but winning neither, rankled when Avildsen did take home a statuette for the film.)

The change is telling, as Avildsen’s low-key direction is replaced by Stallone’s clunkier and more obvious technique. The first film is so naturalistic that it often seems like a documentary. Rocky II, in contrast, never seems anything but a movie. The blunter ‘happy ending’ is but the most obvious sign of this.

Stallone, for example, throws in a couple of gags that are right out of the “Punch Line Ahoy!” joke book. At one point, a character suggests that Rocky invest the money he won from the first fight in condominiums. Looking abashed, Rocky confides, “Condominiums? I never use them.”

Later, when he instead goes on a spending jag and blows his admittedly modest winnings (to help explain why he’ll later break his promise to Adrian not to fight again), he buys himself a sports car. The more sensible Adrian frowningly wonders if they need a car, and repeatedly asks him if he even knows how to drive. He assures her he drives like an ace, and then we jump to a shot of the car humping down the street in an awkward stop-start-stop-start fashion. These ‘comic’ moments, I must admit, failed to endear the film to me.

Even so, to the extent that he could while betraying the fundamental heart of the first film, Stallone took care to tie this chapter into the initial movie as much as possible. As the series became more cartoony, and Rocky more of an all out action hero, the running times became stripped down and the increasingly ridiculous boxing matches began to take center stage.

Here, however, as with Rocky, the fully two-hour running time spends a lot more time on the normal lives of Rocky and his Friends, and again it’s not until the final half hour that the Big Fight fully takes over.

Even so, because this entry is centered on Rocky winning the fight, the climatic bout drives the plot more. Apollo becomes more of a presence throughout, as opposed to the distant, almost god-like figure he cut in the first movie, in which he embodied Rocky’s wildest dreams. We even see a little of his home life, and meet his wife, previously unmentioned. Luckily, Carl Weathers is an interesting actor in his own right, and we don’t begrudge him his larger role here.

Even better, Burgess Meredith’s role as Mickey is greatly expanded. Meredith, nominated for Best Supporting Actor for the previous chapter, chews the scenery with even greater relish here. He’s a delight whenever he’s onscreen, and certainly brings a lot more juice to the proceedings than Stallone’s mumbling, ersatz method acting technique.

Adding to the sense of continuity, Stallone clearly strove to bring back just about every actor who appeared in the first film. (Although whether it was strictly necessary to bring back his brother, Frank Stallone, as a neighborhood street singing dude, is debatable.) Indeed, except for actor Thayer David, who sadly had recently passed away at the age of 51, I don’t particularly recall anyone of importance in the first movie who isn’t seen here.* Considering that there was a three year gap between the two pictures, this is fairly impressive.

[*Oddly, Stallone is the one who looks the most different. I guess we can chalk that up, though, to the beating his face took in the first movie.]

Stallone also took evident pains to reference and carry over as many plot elements from Rocky as possible. Paulie still hectors for Rocky to get him a job with Gazzo, his former loan shark employer. Rocky’s nose, proudly unbroken up until the Creed fight, is referenced several times. Aside from human characters, we see Rocky’s various pets (purchased as an excuse to hang around Adrian, who worked in a pet store). Rocky’s dog Butkus (in actuality Stallone’s real life pooch of the same name), his turtles Cuff and Link, and his gold fish Moby Dick all make appearances.

He also mitigates the plot surgery as much as possible. The first five minutes of the film is a replay of the climatic fight from Rocky,* only here it’s recut and with additional footage added. (This seems like excess footage left over from the original shoot, and not freshly shot inserts.) Here for the first time it is suggested that Rocky was but seconds away from actually beating Creed, before the fight was ended by the final bell. This is a markedly different take on events, and is clearly meant to substantiate the idea that Creed’s victory was a close-cut thing, and perhaps even an unearned one.

[This device, of starting each sequel with a filmic recap of Rocky’s most recent Big Fight, is employed in each of the first three sequels.]

Rocky II isn’t a failure by any means. However, even at its best it generally just provides a second serving of stuff we already got the first time around. When Rocky proposes to Adrian, he does so in a cold, deserted zoo. This, presumably, was meant as a call back to the couple’s whimsical first date at a deserted ice skating rink. The scene itself is sweet, but again maybe just tries a little too hard.

And when second helpings aren’t the order of the day, the sequel’s more overt artifice comes to the fore. Rocky was very sparing in using music, especially before the big training montage that didn’t even appear until an hour and a half in. Here we get a more standard opening credit sequence, as Rocky’s ambulance goes through the city following the Creed fight. This sequence is accompanied by a rather standard orchestral score, again provided by composer Bill Conte and featuring riffs on his music from the previous movie.

At the hospital, an enraged Creed (both fighters have been taken there due to the severe beatings they exchanged) angrily and publicly accuses Rocky of getting by on pure luck. Only later, in private, does Creed assure Rocky that “I gave you my best.”

Rocky heals up, and putting the fighting game behind him, begins his new life. He’s assured that he’ll make a killing doing advertisements, proposes to and marries Adrian, and less helpfully, blows all his money from the fight. (An at-that-time hefty, although hardly gigantic, $37,000.)

During this, Adrian stands on the sidelines and frowns, which sadly will become her major role in the remaining movies. She will often be seen frowning and fretting and crying when Rocky decides to fight again…at least when she isn’t encouraging him to do so. [See Rocky III coverage below.] However, it all starts here as she worries about the future and whether her husband should be so cavalier with his one-time nest egg.

Her fears prove prescient, as Rocky’s career as a spokesman is quickly derailed. Not only can he barely act (a situation exacerbated by nervousness, as well as the hostile reaction that greets his initial floundering), but he is barely literate, and thus has trouble reading his cue cards.

With that option forestalled, and with fighting off the table due to his promises to a now pregnant Adrian, Rocky can only get a job at the meat packing plant where he once trained. A brief montage indicates that this is pretty gross work. Still, it’s honest toil, and he’s content to be bringing home a paycheck. Sadly, though, hard times force the plant to lay him off, and things really hit the fan.

During this, we cut to Apollo, who in contrast is living the American Dream, with a gorgeous home and beautiful wife and children. However, he remains in a stew of humiliation and rage over the fight, which he had intended merely to be a showboating publicity stunt. Now he broods over a flood of letters accusing him of all but throwing the fight, or instead of actually losing it and only being awarded the victory because of his pull. (Which, as mentioned, the recutting of the fight recap at the beginning of this film would seem to indicate.) His pride challenged, he becomes obsessed with drawing Rocky back into the ring, by hook or by crook, and even engages in a smear campaign designed to goad Rocky into action.

These factors, along with Rocky’s elemental need to box—well, and the fact that this is a Rocky movie—all contrive to force Our Hero’s glove. As noted, this creates a bit of a thing with Adrian. Aside from the normal concern that her husband will be humiliated not to mention be beaten to a pulp on a national stage, she must worry that he will be blinded, as his eye was injured in the first fight. (Actually, despite a lot of lip-service to the eye issue, it’s basically forgotten once the boxing starts).

I again must stress how ill-served Adrian is by the series’ ever-escalating sense of melodrama. Here, Rocky risks being blinded. As the series continues, assuming memory doesn’t play me false, he is similarly threatened with being crippled or even killed, should the latest My Last Fight go awry. This serves to rather unfairly sabotage Adrian’s likeability, as much of the time we see her she’s engaged in another hectoring attempt to keep her husband from doing What A Man’s Gotta Do. Which, after all, is what the ticket buyer paid to see.

Anyway, Rocky decides he’s gotta do etc., and begins training. There’s a problem, though, as Mickey realizes that Rocky’s heart just isn’t in his conditioning.* This is due, we intuit, to his lingering guilt about going against Adrian’s wishes.

[*This is too bad, as the training sections of the films are always a highlight. During these, we marvel at Stallone’s admittedly amazing physical condition and strength. It’s even better here, as this is also the most Mickey-rific section of the movie. As usual, while his opponent is seen training in luxury, Rocky must use bargain basement training equipment (here he pounds junk at a dump) and methods. For instance, Mickey works to increase Rocky’s foot speed by having him chase a chicken. Really. It’s stupid but marvelous at the same time.]

The whole ‘not really training’ subplot is disastrously bad, and emphasizes exactly how this movie mucks up the first one. The first time around, Rocky knew he couldn’t beat Apollo, and decided that victory involved not being directly beaten in turn. However, the thin reed of plausibility for even that rested on the idea that Creed was treating the whole match as a joke. After all, when you get down to it, the fight was between the world champion at the peak of his form, and a lug with a lot of heart but not much else.

Here, the situation is completely different. A humiliated Creed makes it clear that he intends to answer his critics, and his own inner doubts, presumably, by beating the holy hell out of his opponent and knocking him out as soon as possible. We see Creed’s intensity and focus throughout, and frankly speaking, he should mop the floor with Rocky from the get-go.

However, we are clearly now in fantasy land. Not only will Rocky beat a Creed who is at the very top of his game, but in classic action movie fashion, do so with both hands tied behind his back. This is like the lame cliché of the action hero who can only face his Most Powerful Nemesis after sustaining some wound. The idea, of course, is to make his victory even more improbable and thus, at least theoretically, more impressive.

This is the same sort of thing. Rocky must not only face a fully engaged Creed, one twenty pound heavier and with a patently longer reach, but do so with a bum eye and after diddling away a significant portion of his training period, during which his foe is seen preparing like a madman. However, this doesn’t make Rocky’s upcoming victory (oops, sorry) more impressive, it makes it more retarded. I guess I’m just not getting into the spirit of the thing, but I just can’t buy Rocky beating Creed. So this heaping-on-of-burdens stuff ain’t exactly helping.

Speaking of melodrama, Adrian about this time goes into labor. She manages to deliver her baby, but goes into a coma. She eventually comes out of it after a long, ‘suspenseful’ hunk of movie—supporting characters didn’t actually start tragically dying start until Rocky III—whereupon they greet their son, and Adrian saves the day by looking up from her sickbed and suddenly commanding her husband to “Win!” Gee, that’s handy.

Now safely Pure of Heart again, Rocky begins the anticipated training montage, again set to the rousing “Gonna Fly Now.” He once more jogs through the city only to end things by scaling the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. This time, however, he’s joined as he runs by dozens and then seemingly hundreds of small children (!!), who all hop around in ecstasy with him as the song reaches its triumphant crescendo. I mean…yeesh. And so another piece of the series’ credibility bites the dust.

The fight finally gets going, again during the final quarter of the movie, but is rather more bombastic than in the previous movie. (Although nothing compared to those in the later films.) In pretty much any boxing movie, punches inevitably land with more, and more consistent, authority than in real life. Even so, they really push things here, as Apollo and Rocky absorb a laughable amount of pummeling from each other. Clearly, both these guys should have been dead by the second or third round, had they managed to last that long.

As if vying to make Rocky’s already ridiculous victory as epically moronic as possible, the bout ends at the very finish of the 15th, with Creed slightly ahead on points (he could have won the fight just by staying away from the staggering Rocky, you see, but A Man’s Gotta blah blah). Landing their last blows, and with the ringing of the final bell just moments away, both men drop insensible to the floor. Who will rise to claim victory in the final seconds?! Oh, the suspense! THE SUSPENSE!!

It’s Rocky.

And..Joyous Victory Freeze-Frame, and see you next time.

*****

Rocky III opens with the now familiar fanfare as the title again scrolls across the screen. Only now, instead of the lettering appearing over a black screen, it moves over the Heavyweight Champion’s belt. Next, as with Rocky II, we are afforded footage from the previous movie’s climax, to remind the audience of how things ended. Remember, this was back before you could just rent the last movie on home video. (Also, and forgive my cynicism, but it’s pretty cheap to pad out your new film by cramming in a hunk of footage from the prior one.)

As previously indicated, the ultimate climax of Rocky II is outrageously cheesy and forced. Here, however, and given the direction that the series more forthrightly takes with the third chapter, that’s only appropriate. We get to relive for several minutes the (to most) pleasing triumph of the second movie, and then move confidently into the cinematic ’80s as the film proper begins.

This is cued by opening notes of the movie’s theme song, Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger.” This was a hugely successful tune. It not only received near-constant radio airplay, but the inevitable music video was lodged in MTV’s heaviest rotation cycle for a long stretch of time. Back before IPods and such, such things guaranteed mass awareness and represented incalculable amounts of free publicity.

Given this, one really has to wonder how much of Rocky III‘s success was due to this lucky fluke. Certainly the series had been blessed by the theme song gods, since “Eye of the Tiger” proved an even huger hit record than the first film’s “Gonna Fly Now.” And that’s saying something.

As noted, it quickly becomes clear that the Rocky series has left the ’70s ‘small film’ mentality behind to fully embrace ’80s-style oversized filmmaking. The previous two films featured but one musical montage sequence apiece, as Rocky trained to the soaring lilt of the inspirational, nearly gospel-inflected “Gonna Fly Now.” Those sequences occurred after each film was three-fourths over, and following a deep, prolonged focus on the personal lives of Rocky and his supporting cast.

In contrast, the aggressively percussive beat of “Eye of the Tiger” accompanies a montage that literally starts the new film off. [Note also that “Gonna Fly Now” is basically interior, a song about self-actualization and being all that you can be. “Eye of the Tiger,” in contrast, is about proving your superiority by the besting of others.] Again, the increased use of music in this film is very ’80s, and a mark of how influential MTV was at that time.

As the sequence continues, we see Rocky continue his championship ways as he defends his belt in several matches. I have to say, the political incorrectness of the Italian Stallion beating on a succession of larger black opponents doesn’t really bother me all that much. However, the credibility of such a thing is another matter. It’s not like we’ve had a parade of dominating white (and small) heavyweight champions over the last several decades.

With this, the boxing elements grab the early center stage for the first time, as Rocky morphs more or less into a largely cartoonish superhero type of character. Meanwhile, as the montage continues to tell its tale, we get what was for the vast majority of the public our very first at the soon-to-be famous Mr. T, here seen to be a glowering onlooker at several of Rocky’s matches.

I should note that, although watching the films in a compressed time period really emphasizes how significantly the latter movies stray from the slice of life sensibility of the first film, this is an exciting sequence. As “Eye of the Tiger” pounds away, the montage ably manages to suggest that Rocky’s victories seem entirely and increasingly too easy, especially in contrast to his brutal bouts with Apollo Creed.

It’s thus a canny moment when the focus shifts and the song starts accompany a typically low-tech Rocky-style training montage, only one centered on Mr. T’s Clubber Lang. As a lighthearted Rocky effortlessly disposes of a series of foes, Clubber is seen rising through the boxing ranks, only while dispensing far more ferocious maulings.

As Rocky slides into a fat and effortless existence of easy victories, easy money (apparently he’s surmounted his previous difficulties in the advertising game) and mass public adoration, the single-minded Lang is seen viciously climbing over the bodies of his opponents, forging the way to his own meeting with destiny.

Before the montage is even over—it’s a remarkably efficient piece of work, and could easily be the focus of any class on film editing—we observe how cannily Rocky III hits its targets. One can easily argue that the series’ lowered goals of moving purely into audience-pleasing entertainment are a little crass. Even so, and unlike Rocky II, which desperately sought to only become a little bit pregnant in terms of giving the viewer the sort of pure wish fulfillment the original Rocky avoided, here the series fully embraces its new direction.

This new focus might be a tad vulgar, but there’s no doubt that Rocky III more honestly and effectively achieves it, and occasionally with great skill and panache. It’s junk food, but well made junk food. Mourn the lost and subtle gourmet delights of the first film if you wish. However, the fact remains that Rocky III unabashedly serves up the comfort food (sorry, am I overplaying this metaphor?) its audience wants, and with less hypocrisy than the conflicted second entry.

As the montage continues, we shift from an angry looking Clubber watching Rocky’s matches to a worried looking Mickey watching Clubber’s. Then, as the intro fades, we catch up again with Paulie, who himself is patently angry and petulant over all the (real-life) Rocky paraphernalia he sees everywhere. (Has there ever been a non-villainous regular character in a major movie series who’s a bigger jerk than Paulie?) Finally he goes a bit berserk and shatters a (real-life) Rocky pinball machine. This, naturally, he sees as he wanders through a packed video arcade. Rocky III was made in 1982, after all, when there were laws mandating that every movie had a scene in one of those.

Rocky, appearing newly sleek with his tailored suit, swept-up coif* and camelhair coat, comes to bail Paulie out. They argue and even fight a bit (well, Paulie does), but soon patch things up and establish that Paulie will join Rocky’s ring crew.

[*Since the Rocky series was at least semi-autobiographical, Rocky’s newly sophisticated image at least partly reflects the changes in Stallone’s life following his success playing the boxer. Sort of like the Roseanne TV show, in which the character eventually wins the lottery to better follow the changes in her portrayer’s life. As for the poofed-up hair, one suspects it was intended to allow Stallone to ‘legally’ misstate his height. For instance, he’s listed on the IMDB as being 5′ 10″. Even to the extent that it’s accurate, I think an inch or two of that might be hair.]

We spend some time with Champion Rocky. Whether as a result of the series’ new focus, or perhaps rather a cause of it, the personal stuff in this movie often seems, for the first time, a trifle stale and precious. It may simply be the case that ‘happy, satisfied, loved Rocky’ just isn’t that interesting. For the first time in the series, however, the viewer finds himself wishing they’d just get to the boxing already.

Here we also get the series’ first descent into outright camp, as Rocky engages in a charity bout with the world wrestling champion, as played by the then largely unknown Hulk Hogan. Hogan literally dwarfed Stallone by maybe a foot, and nearly two hundred pounds, and the match is played for laughs. Unprepared to be actually assaulted, Rocky takes a beating from “Thunderlips,” until Our Hero strips off his gloves and takes care of business. The scene is enjoyable, but really puts paid to any remaining slivers of reality the series still had.

Then it’s back to the plot. We join Rocky and the family at the dedication of the real-life, 8′ 6″ Rocky statue on the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where the character famously and triumphantly ended his training montages in the previous two movies. (After filming was wrapped, Stallone actually donated the statue to the museum, resulting in a continuing, now decades-long controversy.)

To the shock of the crowd, but the visible relief and approval of Adrian and Mickey, an emotionally overcome Rocky announces his retirement from boxing. However, the moment is ruined when Lang, now the number one contender for the heavyweight belt, emerges from the crowd and issues an angry, insulting challenge. He charges Rocky with only fighting pre-selected losers, all while cravenly ducking a bout with Clubber. Rocky is angered by these charges, and nearly accepts Lang’s challenge, but is interrupted by a visibly frantic Mickey, who pulls him away.

Back to the Rocky Mansion. Paulie has recently moved in, joining Rocky, Adrian, the couple’s young son and, as it turns out, Mickey. (!!) It’s a virtual clubhouse they’re running there. Anyway, disturbed by Lang’s charges, Rocky confronts a frail-looking Mickey, who he finds packing his belongings. Mickey snarls that if Rocky fights Lang, it will be without his help.

When Rocky pushes the matter, Mickey confesses that he has indeed been working behind the scenes to keep Clubber out of Rocky’s path. He assures Rocky that his previous opponents have been good fighters, but admits that they were nothing like Lang. In the film’s most famous line, Mickey warns, “He ain’t just another fighter! This guy’s a wreckin’ machine!” Moreover, he confesses that Rocky has lost his edge. “The worst thing that happened to you, that can happen to any fighter: you got civilized.”

His vanity stung, Rocky demands to fight Lang, and jollies Mickey into training him again. However, despite his promises, when we see Rocky training, we find that he (paralleling Creed’s reaction to him in the first movie) isn’t taking Lang seriously. Rather than retreating to their old gym to train, Rocky has rented a lavish public hall, where he spends his time ignoring Mickey and mugging for the fans. The hall is also full of Rocky kitsch and merchandise, including a gigantic LeRoy Nieman Rocky painting.*

[*We see more Nieman work under the closing credits, and the artist even has a cameo as a ring announcer. Stallone gained a reputation as an art collector during this period, and I assume Nieman had become a friend of his.]

Meanwhile, Clubber is training in much less luxuriant surroundings. If the Rocky movies teach us anything, it’s that he who trains in the scuzzier (i.e., more ‘authentic’) facility will win the fight. (Yeah, because I’m sure Muhammad Ali and George Foreman at the peak of their success trained in vile rat holes.) So Rocky’s fate is pretty much sealed already. On the other hand, since this scene also features the series’ third opportunity for Sly’s famously untalented brother Frank to croon a song at us, I figure Rocky deserves a healthy beat down.

Rocky indeed emerges from training with a more ripped form. This reflected the ethos of the time, when all action heroes needed to be heavily veined and overly ‘cut’ muscled hulks. Still, is he easily physically overmatched by Lang, who outweighs him by nearly 40 pounds of bone and muscle.

As they prepare to enter the arena, Rocky and Lang nearly come to blows in the hallway. Mickey is tossed aside by Clubber and afterward is in much apparent distress. (They’ve been playing up his health issues throughout the movie.) Once in the ring, moreover, Clubber dares to publicly diss Apollo Creed, who is attending the fight as a commentator. To the modern eye, the two have a definite Muhammad Ali / Mike Tyson dynamic going.

Angry and arrogant, Rocky ignores Mickey’s advise and stands there trading blows—sledgehammer punches of the sort only seen in movies—with Lang, who again is younger, fitter and quite a bit bigger. In the second round, a staggering Rocky is knocked out, and Lang is the new champion.

A chastened Rocky goes back to his dressing room, where he finds Mickey moments from death. (Yeah, like they wouldn’t have taken him to a hospital.) Rocky misleads the failing Mickey into thinking that they won the fight, and as he expires, Mickey tells Rocky that he loves him.

As you can imagine, the schmaltz here is pretty thick, but effective nonetheless. Kudos especially to Meredith, who took the utterly cliché part of the gruffly irascible yet loveable old trainer and really made it work. As you might expect, with the third movie being so exaggerated, Meredith was encouraged to chew the scenery with even greater gusto than before. I have to say, I think he remains the best thing in the series, and his absence following this was definitely felt.

In the end, it’s Apollo who steps in to convince Rocky to challenge Lang to a rematch (presumably because Clubber publicly punked him). Having Rocky’s old rival step in as his new trainer is more ‘movie logic’ than anything that would make sense in real life, but there you go. It’s Creed, by the way, who urges Rocky to reclaim “the eye of the tiger” (what came first, the song or the scripted line?), and he uses the phrase often enough throughout the rest of the movie that you could easily make it the subject of a drinking game.

In order to make sure he’s better prepared this time around, Apollo and Rocky fly out to L.A., where they will train at the gym that Apollo himself started at. This is even scuzzier and more dilapidated than Mickey’s old gym, so you know, it’s a good sign. As in the previous movie, however, Rocky is even now half-hearted in his training, to Apollo’s increasing frustration. This time, it turns out, it’s became he’s suffering from PTCLAWS (Post-Traumatic Clubber Lang Ass-Whoopin’ Syndrome).

In the end, it’s Adrian who convinces him to fight again. This is clearly solely so that Talia Shire has a ‘big scene’ in the movie, but it makes little sense. Lang is clearly more dangerous than Creed, who she didn’t want her husband fighting in the last movie. So why encourage him here? By the way, the big plot point last time was that Rocky had a bum eye and could have been permanently blinded if he fought again. Yet the eye isn’t even mentioned this time around.

We know things are back to normal when the strains of “Gonna Fly Now” start playing over another training montage. The orchestration has been slightly remixed, though, with a bit more of a disco beat. Needless to say, the whole magilla finally wraps with the now obligatory Rocky Triumphant Freeze-Frame.

During the sequence, Rocky and Apollo (in a midriff baring shirt) are shown training and sweating together, with many straining, heaving slo-mo shots. Although I’m not one to toss around the phrase ‘homoerotic,’ well, it’s hard to avoid right here.

The sequence ends when Rocky beats Creed in a footrace, because if there’s any area in which whites have even more of an edge over blacks than in boxing, it’s in track. Watching the runty Stallone outpace Creed literally had me laughing aloud. Meanwhile, they celebrate by, and I’m not kidding, having the two half-naked, glistening men embrace in the surf (Apollo in his half-shirt), and jump up and down in each other’s arms. In slow motion.

Anyhoo, Lang quickly accedes to a rematch (of course he does), in which he promises to wail on Rocky even more severely. It’s in an interview here that Mr. T first unleashed what would quickly become his trademark line. When asked if he hates his opponent, he shouts, “I pity the fool!” And a Star was Born. Another great Mr. T moment quickly follows, when he is asked for his prediction for the fight. Glaring into the camera, he responds with a growled “Pain!”

Meanwhile, we get a Big Moment during the pre-fight scene when Apollo gives Rocky his [Apollo’s] old red, white and blue boxing trunks (!!)—yeah, like they’d fit—while also reminding Rocky that he’ll owe Creed an unstated something should he win the fight. This is a running gag in the movie.

The fight goes about how you’d expect. Rocky counterintuitively has shed another ten pounds, which might make him faster, but gives Lang a nearly 50 pound weight advantage. The two trade enough blows to kill half a dozen real people, each of which lands squarely.

However, Rocky apparently is using his +20 Boxing Gloves of Invulnerability—employed to even more ludicrous extremes in Rocky IV—and basically exhausts Clubber by encouraging him to punch Rocky right in the head about a hundred times straight. “He’s getting killed!” Apollo groans. “No, he’s getting mad!” Paulie retorts. Once Lang falters against his now literally inhuman foe, Rocky unleashes the expected fusillade of Mighty Blows, and lays Clubber low.

The coda occurs when we later see Rocky and Apollo entering a deserted gym. Jocularly, the aforementioned favor Apollo now demands is for a private rematch, and we (inevitably) freeze-frame as these doughty warriors and now best friends begin their fisticuffs. Cue the end credits, played over a second rendition of “Eye of the Tiger.”

Pingback: JABOOTU the bad movie dimension » Blog Archive » Michael Pataki RIP

Love your reviews Ken, I’ve recently gotten into your old site and wanted to see a Rocky 4 review so I’m glad that you put all this work into reviewing ALL of the movies, really enjoyable and good reviews that clairfiy a lot of your thoughts on the series.