When Elizabeth Taylor passed away earlier this year, it marked the loss of one of the very greatest screen icons. Any number of clichés will do, but I’ll go with ‘They don’t make ‘em like this anymore.’ Taylor began her career as a child actress during Hollywood’s Glamour Age, making films like Lassie Come Home and National Velvet. This was back when stars, in a professional sense, were more or less owned by their studios; much as baseball players were by their teams.

Ms. Taylor then grew into adulthood during the period when the major studios’ dominance began to crumble. As the power of the companies and the old school moguls who ran them waned, the power of the ‘talent’ grew apace. 1948 saw U.S. v. Paramount Pictures, et al, the antitrust case which forced the studios to divest themselves of their wholly owned chains of theaters. The studios would continue making films, but the theaters showing them became independent entities.

The ruling marked the beginning of the end of the fabled studio system. Shortly thereafter, Jimmy Stewart furthered the process by accepting a percentage of the profits in lieu of his normal salary for 1950’s Winchester ’73. The film was a tremendous hit, and Stewart’s subsequent financial windfall soon saw similar deals become increasingly common.

Concurrently, the American public developed an ever more ravenous taste for scandal. Inevitably, the stakes had to keep being raised; what had been a major scandal in yesteryear would barely raise an eyebrow not long thereafter. We’ve now reached the logical conclusion of that process. Indeed, in a world in which an Oscar-winning actress can dismiss the forced sodomy of a sobbing twelve-year old as falling short of “rape-rape,” one wonders whether ‘scandal’ conceptually can even be said to exist any longer. Poor Fatty Arbuckle, a man simply born too soon.

Elizabeth Taylor’s life and career not only spanned these eras, she was a central figure in the transition from the Glamour Era to the Age of TMZ. She raised eyebrows when as a young but already thrice-married star she seduced and stole away singer Eddie Fischer from his publically beloved and rather more wholesome wife, actress Debbie Reynolds (not to mention his young daughter, Carrie Fischer).

Ms. Taylor’s in your face nonchalance on the matter shocked the older set. Powerful industry gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, used to having even the most powerful stars cower before her disapproval, was rather nonplussed when Taylor shrugged, “What do you expect me to do, sleep alone?”*

[*To be fair, Eddie Fischer was at that time the only living human male on the planet.]

Mr. Fischer got his comeuppance a few years down the line when Ms. Taylor went to Italy to make the legendary cinematic megabomb Cleopatra. Her co-star Richard Burton had been heard to dismiss her as “Miss Tits,” but once exposed to her great beauty and her yet evident reluctance to sleep alone, he quickly succumbed to her charms.

Their affair shocked and titillated the world. The Roman Catholic Church, which still did stuff like that back then, publically excoriated the couple. As with Ms. Hopper, however, they found their cultural relevance largely dissipated. If anything, their rebuke served mostly to pump up ticket sales when the seemingly cursed production finally hit screens. Even so, the film’s massive production overruns still nearly sank 20th Century Fox. The studio was only saved by the insanely popular The Sound of Music.

Ms. Taylor had been on a real career roll before yoking herself to Burton. Immediately before starring in Cleopatra, Taylor had received an astounding four Best Actress nominations in a row. She finally won the fourth time, predictably via the popular gambit of playing a prostitute, in Butterfield 8. However, it is one of her weaker nominated performances. Conventional wisdom has it that she won thanks to the sympathy vote following her then recent and nearly fatal bout of pneumonia.

Such musings aside, Ms. Taylor had beaten tremendous odds by successfully transitioning from a child to adult star, perhaps more successfully than any other actor in film history. By the time she met Burton, she reigned as Hollywood’s greatest, most beautiful and most glamorous female star.

However, Ms. Liz’s taste for ever edgier—arguably trashy—arty fare proved the chink in her armor. For several years this placed her on the industry’s cutting edge, starring in acclaimed social dramas such as A Place in the Sun (although frankly I find the film wildly overrated). Then she went over the edge. Way, way over the edge. And the man who steered her over that precipice, both professionally and personally, was Richard Burton.

The masculine allure of Jabootu’s earthly avatar drew Ms. Taylor into quite possibly the greatest run of Grade A crapola in film history. Those four Oscar nominations and one win were followed in short order by Cleopatra (not a horrible movie, but quite possibly Hollywood’s single greatest bomb), The VIPs, The Sandpiper, Doctor Faustus, Reflections In a Golden Eye, Boom!, Secret Ceremony, Hammersmith is Out, The Bluebird and others. The majority of these works, which rank among Jabootu’s greatest achievements, co-starred Burton, who by then was her husband…and then not her husband and then her husband again.

Jabootu wisely strengthened its hold on the pair by allowing them back to back successes amidst the dross. Taming of the Shrew was a genuine success, while Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? actually achieved the sort of cutting edge artistic acclaim the pair so desperately lusted after, but would never again garner. Ms. Taylor won her second Best Actress Oscar for the film, one that this time was undisputedly deserved.

Ironically, Ms. Taylor chose not to attend the Academy Awards that year. Burton, a perennial Oscar loser—he never did win one, despite seven (!) acting nominations*—was clearly going to lose again, this time to Paul Scofield for A Man For All Seasons. (Hard to argue with that, though.) The couple stayed in Paris during the awards ceremony as a sign of their mutual displeasure.

[*I still remember a bit on SNL years later, where John Belushi reamed out host Richard Dreyfuss, after the latter had beaten Burton and won Best Actor for The Goodbye Girl, a rare win for a comedic performance. Burton had been a heavy favorite for that year’s Equus, if only because of the Academy’s long and not particularly noble history of giving veteran actors a ‘career’ award. Dreyfuss unexpectedly prevailed, however, and it proved Burton’s final nomination. His next film was The Medusa Touch.]

Riding high on a heady combination of commercial and critical success, the couple was a lamb for Jabootu’s slaughter. One of their subsequent collaborations, arguably their single greatest, was today’s subject. Were there a Jabootu’s Top Ten, Boom! would certainly make the cut. It is, arguably, the film that stands directly opposite Citizen Kane on the Cinematic Bell Curve.

I should note that I myself broached the idea of a posthumous B-Masters roundtable dedicated to Ms. Taylor’s epic parade of big budget, high profile crap. (A suggestion partly motivated, I must admit, by an urge to prod my fellows to examine the sort of glossy Hollywood fare we too seldom survey, as well as to afford the first topic in a while for which I wouldn’t have to flail around looking for a suitable subject of inquiry.) Several of my compatriots evinced marked unease with the idea, however. One suggested that it would look like we were kicking Ms. Taylor in the wake of her death.

Such a thought never entered my mind. The fact is, Elizabeth Taylor starred in an astounding array of Jabootu’s greatest works. Other stars faded from the screen. Ms. Taylor doused herself with cinematic gasoline and lit the fuse, again and again and again. Misguided as her efforts may have been, there is a very real majesty to these films. Sort of a crazy King George sort of majesty, perhaps, but it’s there nonetheless.

If there was one thing Ms. Taylor never sought, it was the comfortable safety of mediocrity. It was not her way to go gently into that dark night. So come, gentle reader. Let us raise our glasses high and give a toast to the mad, magnificent glory that was Elizabeth Taylor. We shall never see her like again.

Talk about truth in advertising.

We open on the image and sounds of waves crashing upon rocks. There’s some kind of metaphor there, I’m sure. After all, nearly every element in the film is meant to be a metaphor for something or other. And there’s no score during any of this, because it’s Art. Ms. Liz gets the first credit, followed by Burton, followed by Noel Coward (!).Then, in pretentious Roman-style lettering, we get “IN THE JOHN HEYMAN PRODUCTION OF JOSEPH LOUSY LOSEY’S…”

I guess Williams lost the rock / paper / scissors tourney.

The camera draws back, and reveals…ugh, the name of Michael Dunn in the supporting actor credits. Oh, Dr. Loveless, I never thought you would sink this low. (On the other hand, he also played a leering necrophiliac in Frankenstein’s Castle of Freaks, a film not overmuch better than this one.) Anyway, the shot establishes a forlorn balcony overlooking the remote, desolate shoreline. A keening wind…oh. John Barry did the music. Well. We’ll just call that a mulligan, shall we?

Tennessee Williams himself wrote the screen translation of his play, upon which the film is based. So no avoiding blame there. As we shall see, Mr. Williams’ current subject strays rather afield (in some ways) from the Southern Gothic style with which he won his great fame and riches. Sometimes the problem of trying to get out of your rut is that it’s the only rut you’ve got.

A further establishing shot places the action on a foreboding, if sundrenched island. Here sits the horrendously modernist mansion—constructed for the film at the cost of a cool half million—of Flora “Sissy” Goforth (yes, really), the richest woman in the world. Three guesses who plays Ms. Goforth. And is ‘Sissy’ some sort of half-assed allusion to Sisyphus? It would certainly suit the ponderous air of poseur intellectualism that embodies the project. See, Our Protagonist’s last name is “Goforth,” indicating an inherent nature of forward movement. Yet, Sisyphus indicates…well, you get it. Anyway, what a fabulous dichotomy, eh? Really makes you think.

We cut inside to see a small army of maids arduously striving to keep the mansion’s all but deserted expanses spotless. A tall dark manservant in a red robe and turban bears a small tray supporting an ornate stemmed cocktail glass. He wends his way through the mansion until he reaches a bed, one where a masseuse and a manicurist are attending to the somewhat fleshy naked back and fingernails of Our Putative Heroine. Ms. Goforth is also attended by the inevitable useless-looking lapdog. A literal one, I mean, although I’m sure it’s symbolic too. I mean, why stint at this point?

Without bothering to look at its bearer (CHARACTERIZATION!), Ms. Goforth reaches out and gloms onto the cocktail. We still haven’t seen her face, because…hell, I don’t know. I’m sure there a good reason, though, don’t you think? I mean, they paid Liz—and Burton as well—a million smackers to star in this film, which was a simply tremendous sum at the time. So you’d think they’d, you know, show her face or something.

Sadly, for Ms. Taylor, director Losey nixed her suggestion that she play the entire movie with her back to the camera.

The dog, meanwhile, wanders away in apparent boredom. This presumably unplanned moment will thus represent the film’s sole successful moment of SYMBOLISM!

Suddenly Ms. Goforth has a convulsive fit. Plot point! Reaching towards a speaker box, she calls her personal physician to come give her an injection. She smashes aside the cocktail when it is again proffered to her, then reaches out to what apparently is an attaché case-sized intercom control box. It looks ludicrously oversized now, but I’m sure it represented the very ritziest cutting edge of consumer electronics at the time.

This movement allows the camera to dwell upon Ms. Goforth’s jewelry. The showcased artifacts include an oversized and rather gaudy diamond bracelet, and an even more ostentatious diamond ring, one bearing a stone roughly the size of a manhole cover. This latter object gets its own loving close-up, although that may have been accidental. It’s so large that possibly it inadvertently exerted a gravitational pull upon the camera.

You know, any halfway decent agent would have gotten this ring fourth billing after Noel Coward.

Publicity for the film emphasized that Ms. Taylor was adorned with two millions dollars’ worth of gems for the film. I can’t even imagine what that would translate to in todays’ dollars. Although loaned to the film by Bulgari of Rome, there’s nothing on the screen Ms. Taylor didn’t personally own the equal of. She had a legendary appetite; er, for diamonds, I mean. Burton, following those who came before him, wooed Ms. Taylor in part by buying her a series of staggeringly gigantic stones.

It was all part of the swinging jet set lifestyle that again marked a transition point from the (officially) tastefully glamorous celebrities of yesteryear and the rampantly hedonistic, (overtly) vulgar materialist morons of today. Bette Davis → Elizabeth Taylor → Paris Hilton. This also raises the irony of Ms. Taylor playing a Woman Who Has Everything But Yet Has Nothing while parading her own Brobdingnagian trinkets before the camera for the oohing and ahhing of the hinterland yahoos who made up the moviegoing public.

The close-up of the diamond transitions (ART!) to a blazing shot of the sun. This is accompanied by our first taste of Mr. Barry’s score, which is a snatch of calliope-type music. This accompanies the camera as it pans down to a figure plodding past the small, primitive native village where presumably Ms. Goforth’s army of servants live. This fellow walks towards the camera until he is revealed to be the scruffy Chris Flanders (Burton), dressed all in black—just the thing for hiking along under the Mediterranean sun—and carrying burlap bags tethering a rope looped over his neck.

Burton arrives just as a boat is leaving to go to Goforth’s island. It’s been rented by a Journalist (that’s how he appears in the credits) who’s seeking information and pictures of the World’s Richest Woman. Chris jogs down the hill and hops aboard just as it leaves port, drawing no notice from the busy crew. He then implies to the Journalist that he’s an acquaintance of Goforth’s, although we have our doubts. The Journalist soon figures this out, too, and dumps Chris’ bags into the waters, forcing his uninvited guest to jump overboard to retrieve them. Luckily, this occurs directly off the island.

The Journalist had noted that it was “a bitch” to get to see Goforth, and we now learn how true that is. From her mountaintop home comes the stuttering sounds of a machine gun firing, as plumes of water dance all around the Journalist’s boat. “Bloody bitch of the world!” the Journalist cries, albeit while being forced to retreat. Despite receiving his own credit, this ‘character’ now disappears from the film.

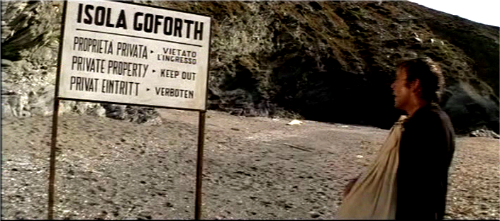

The Carousel Theme starts up again as Chris staggers from the waves, so it’s pretty much officially his theme. Striding along the beach, he soon sees a sign announcing that Isola Goforth is Private Property – Keep Out. (Well, off, I would think.) He chuckles and continues on his way. Reaching the rocks, he calls out “Mrs. Goforth!”, and begins his accent ascent.

Signs that would have been more useful in theater lobbies.

Meanwhile, another (as it turns out) commotion, including barking guard dogs, draws the attention of the island’s mistress, clad in a flowing white muumuu. This raises the question of whether Ms. Taylor’s decadent life with Burton was beginning to take its toll on her famously once perfect physique. Exasperated, Ms. Goforth, well, goes forth to deal with “another goddamned village delegation.”

Again, we see that her gigantic house holds only her and her equally gigantic staff, but no friends or loved ones. Goforth exits out to the mansion’s huge, sundrenched seaside balcony. Here we get several more vantages on the place, which is simultaneously gobsmackingly spectacular and horrendously gaudy. Much like the Mansion Built to Be Exploded in Zabriskie Point, it seems designed to be featured on an early progenitor of Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.

Outside Ms. Goforth joins her security chief, Rudi the Majordomo, as played by Michael Dunn. Rudi is clad in fascist-looking paramilitary gear, including a beret and jodhpurs. Williams probably included a dwarf because Fellini always used them, and nothing says ART! like Fellini. Meanwhile, Dunn always stands at attention, and I assume his military affectations are meant to be comical because he’s a little person. So…screw you, movie. Anyway, they watch as what is indeed another village delegation, ringed by several security details, is brought into Goforth’s presence.

Hmm, I get a feeling they were trying to imply something about Rudi, but I can’t quite put my finger on what.

The village elders have come to demand financial support for the widow of a young man who was killed after he trespassed on Isola Goforth. Goforth responds that the man was a thief, and that if this woman wants money, she’ll get it only if she permanently leaves the island. So…I guess the village is on the island, but the mansion can only be accessed via boat? Ah, well, like it matters. We don’t really hear from the villagers again anyway.

Oh, I just noticed a bunch of Easter Island-style monoliths—fakes, I can only presume—sitting on a hill next to the mansion (!). I’ve heard it said that they supposedly represent Goforth’s dead husbands, although if the film establishes that I missed it. Hmm, you know, Ms. Taylor later became one of the best friends of Michael Jackson during the Crazy Years. Now there was a guy you could see buying Easter Island statues for the Neverland Ranch, had he’d been allowed to.

Anyhoo, having made her pronouncement, Goforth turns and takes her leave. Meanwhile, we spy Chris scaling the rocks. Nearing the top, he pauses and again shouts out, “MRS. GOFORTH!” She can’t hear him yet, however, and she reenters the house. There she stalks through a portion of the gigantic open main space, which features a huge desk and unglassed Fred Flintstone windows hewn into the outside wall.

Without preamble Goforth resumes dictating her memoirs to her private secretary, Miss Black. She pretentiously blathers on about some purportedly witty repartee she shared with “the Prince” at some shindig or other. Again, the idea is that Ms. Goforth represents pretty much the Platonic Ideal of a remote, shallow, cartoonishly self-important rich person. She’s kind of like a distaff Mr. Burns, albeit limned with less depth and nuance.

She drones on, assuming a not terribly convincing English accent.* You know, on The Simpsons Burns would drone on for 20 seconds, and they’d be satisfied they’d made their point. Here the bit goes on for like five minutes (or, arguably, two hours). Admittedly, her extended spiel provides some biographic info on Our Protagonist, such as that she accrued her vast wealth via a series of marriages to “a pyramid of industrialists.” But really, what does that bring to things?

[*Ms. Taylor was, in fact, born in England to American parents. The family lived there until 1939, when Elizabeth was seven years-old. The war looming on the continent then inspired the family to move to the States. It’s possible the accent was bad on purpose, I suppose.]

I realize this was adapted from a play, but there’s really no reason at all the damn movie has to run two hours. Williams would have been better served to cut a tad more ruthlessly. On the other hand, you don’t attract Epic Hambones Great Thespians like Ms. Taylor and Mr. Burton by cutting their monologues, I guess, no matter how many of them there are. If the two had ever subscribed to the Say More With Less school of acting, they had certainly cancelled those subscriptions long ago.

During all this, the Carousel Music starts again. Chris isn’t in sight, so I guess it’s not his personal theme, but instead…a general one? I suppose. Just a comment on the overall wackiness, apparently. Life. It’s just One Big Carousel, isn’t it? Makes you think.

Speaking of making you think, it turns out that *gasp* Ms. Goforth’s marriages to that long series of bloodless tycoons were all sans Passion and suchlike. She only Found Love, she reveals, with her last marriage to (I shit you not) “a young poet.” Seriously, she actually says that. There’s no indication this is meant to be at all tongue in cheek, despite being a line which doubtless provoked more than a few bursts of laughter from the film’s admittedly scant moviegoing audience.

Anyway, the Young Poet tragically died blah blah blah, and hence Ms. Goforth’s present remote existence. This is our first taste of the film’s (and no doubt, play’s) incredibly florid dialogue, and it’s a hoot:

“My name has been in lights since scarcely more than a child. And marriage to five industrial kings, all who had vast fortunes; which, according to the looks of them, they deposited in their bellies. A pyramid of tycoons. But then, after them, was once love. My sixth and last marriage was to a young poet. Light as a bird, who had a passion for altitudes far above sea level…”

There’s a reason dialogue like this is generally described as ‘theatrical.’ (Not to mention stupid.) Theater, with a visible stage and often simple or abstract sets and works divided into scenes and acts following which actors make en masse exits, presents the audience with overt artifice. Film, particularly in a movie theater, is a remarkably different medium. It is more immersive and ‘realistic.’ On stage actors are small, relying on booming voices and exaggerated gestures to reach their viewers. In a cinema, the movie looms literally larger than life over the audience. Much can be read into the smallest and quickest of expressions.

Williams’ work had been translated successfully to the screen; indeed, several of those adaptions (a couple of which again starred Ms. Taylor) are arguably film classics. Even so, it takes a deft hand to make that transition work, and there’s no such hand at the wheel here. Director Losey either lost the fight or never sought in the first place to restrain Taylor or Burton’s infamous proclivities to overact. The results are pretty much exactly what you’d expect. Playing to the cheap seats is again something that works generally better in theater than in cinema.

Still and all, the film was undoubtedly doomed from the start, being based as it was on already twice-failed source material. Originally entitled The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore (hard to believe they changed that title), and even with Williams’ name beguiling theatergoers, the original New York production ran but 69 performances before closing. It was revised and reworked and reopened a year later with a name director and cast, whereupon it closed after FIVE performances. Failed plays and stage musicals generally (surprise!) result in failed movie adaptations. See Paint Your Wagon for another example.

During all this, an unseen Chris continues his approach, his ever greater proximity indicated by the increasing loudness as he repeatedly bellows “MRS. GOFORTH!” Presumably this replicated an offstage effect in the stage version of the thing, and moreover not too subtly SYMBOLIZES! how Goforth, trapped and mired in the past (which in this scene she is literally explicating lest me miss the point) ignores Shouts from the Present. Get it? This is therefore approaching the line were Subtext becomes Text, almost always a dangerous, not to mention obnoxious and presumptuous, line to cross.

However, no character played by Richard Burton is one to let himself be ignored. Eventually his cries are loud enough that Goforth is forced to reply in similar volume, “NO INTERRUPTIONS!” She then continues with her reminiscences, noting how Young Poet demised himself falling down a mountain (one far above sea level, presumably). “Five thousand feet down to his death in a field of snow,” she declaims. “My heart fell with him, and was shattered as he was.” Even allowing for the idea that Goforth’s dialogue here is meant to be outrageously pompous, well, Taylor’s ability to deliver such lines with a straight face remains impressive. Actually achieving dramatic credibility with stuff like that seems rather much to ask.

Despite her best efforts, Ms. Goforth is forced into the present moment (SYMBOLISM!) by the increasing ruckus outside, most evidently all the loudly barking dogs (INADVERTENT SYMBOLISM!). Reacting with fury to the tumult, she sends Miss Black outside to deal with the situation. “Shut them up or shoot them!” she snarls. One imagines Ms. Taylor reacting with similar vehemence to the critics once they started reviewing the film.

We cut outside, where said canines are seen approaching and then mauling Chris. Watching Mr. Burton be savaged by a pack of large, ferocious dogs is sure to please anyone who has sat through The Exorcist II: The Heretic or Bluebeard. I’ve seen both (and many other such examples of Mr. Burton’s work), and I know I enjoyed it greatly. Indeed, Rudi the Majordomo, watching from a hill, seemed nearly as entertained as I was.

Sadly, especially for anyone sitting through this movie, a horrified Miss Black orders Rudi to call off the hounds. (I have to say, those are some well trained dogs to back away from a huge piece of ham like that once they’ve had their teeth in it.) A bloodied Chris, clothes and flesh torn in a matter suggesting, oh, Richard Burton after the notices for The Medusa Touch came out, painfully drags himself up to the balcony and hauls himself over to a large decorative fountain for a sip.

Several members of the household, including Doctor Luilo and Etti the manservant, appear to check out the trespasser. Meanwhile, Chris fills a dish with water and sets it before a monkey chained to a nearby wall. (??) I guess this is to show his Great Heart to something. This attended to, Chris painfully lowers himself into a deck chair and resumes calling “MRS. GOFORTH!”

Richard Burton muses on how Boom! might be the greatest movie he ever made.

Inside, the object of his search is questioning Rudi, asking whether the beach trespassing sign warns “‘Beware of Dogs’?” Told that it does not, she orders Rudi to immediately post a new sign reading to that effect, “In three languages…and Arabic!” (I have a vague hunch that’s meant to be funny, although I certainly can’t defend the notion.) She’s worried that Chris will sue her and wants the sign changed to cover up the lapse. On the way out, the diminutive fellow pauses to glare at Miss Black, presumably for messing up all his fun.

Outside, Chris seems to have garnered a bit of a fan club in both Etti and Doctor Luilo. (This isn’t that hard to believe, since anyone appearing in a bad movie would surely be impressed to be working with Richard Burton. The guy was like a living Jabootu Seal of Approval!) Luilo is ministering to Chris’ wounds, partly with a medical shot of booze for which Chris shows a lot more appreciation than for the water earlier. I assume this is a bit of business Burton brought to the table, since he represents perhaps the least credible teetotaler since W.C. Fields retired from the screen. And I’m including Peter O’Toole in that list.

Etti, meanwhile, is sent to announce Chris’ presence to Goforth and present her with a volume of his poetry. Goforth shrugs the latter off, and tells Miss Black to inform Chris that she [Goforth] is sorry about the whole dog thing, but that she is not responsible for the safety of anyone who comes to the island uninvited. This, actually, sounds exactly right. Miss Black, however, refuses to send the message, feeling it’s insufficiently humane.

Purely because this is a movie, Goforth then orders Miss Black to interrogate Chris as to his presence here. In the meanwhile, he’s to be put up in the aptly named Little Pink Villa. I expect this is EXACTLY what Bill Gates or Oprah would do in similar circumstances. It certainly makes a lot more sense than to call the police to come take him away or having her security guards boat him back to the village. However, it could be that Goforth is, even at a distance, responding to the siren call of Chris’ masculine charms. “I could do with some male companionship!” she japes, after which she stares longingly into the distance as sitar music plays. (!!)

We cut to Chris, who is indeed ensconced in the aforementioned pink domicile. A circular, domed one-room affair, it comes complete with a mountain stream-fed interior pool, cold but suitable for a chilly bath. In an amusing inversion of the normal course of things, it’s Miss Black who casts an appreciative glance at Chris when he rises from the water behind a partially opaque screen. (We don’t get such a look ourselves, no doubt in deference to Burton’s no longer svelte physique.)

She also goes through his bags, which seem to mainly contain flattened black pieces of metal. Questioning these, she waits while Chris emerges clad in a pink robe and towel. Sitting on the floor (hence the towel wrapped around his waist), he assembles the pieces into an abstract but not terribly impressive mobile and explains that “the Earth is a wheel in a great big gambling casino.” This, apparently, is what he’s come to tell Ms. Goforth.

He asks after rumors that Ms. Goforth is in poor health. “She is a dying monster,” Miss Black shrugs. “Seems to think her legendary existence couldn’t go on for less than forever.” Much like this movie, then. By the way, nothing we’ve seen Goforth do really warrants such a harsh judgment. Hell, to one of Hollywood’s legendarily longsuffering personal assistants she’d be considered an easygoing boss.

Miss Black goes on to detail Ms. Goforth’s avoidance of how dire her state is: “[She] Insists that she’s only suffering from bursitis, neuritis, itis this, itis that, this itis, that itis, anything but death-itis.” That’s some great wordsmithery there, Mr. Williams. Congrats. Chris, meanwhile, explains “you could describe me as a professional houseguest.” As Miss Black prepares to leave, he tells her she’s the nicest person he’s met in a long time. Other than, I guess, what she just spewed about her boss. Then Chris disrobes and climbs into bed, accompanied by more sitar music. Welcome to the late ‘60s.

Apparently hoping to burnish Goforth’s credentials as a monstrous harpy, we are soon privy to her insulting her staff and ordering them around. That’s right, she orders her employees around. For instance, she wants them to go fetch the sun umbrella when she goes to sit out on the balcony. GASP! Never has the silver screen portrayed seen such senseless, unmotivated cruelty. Take that, Kevin Spacey in Swimming with Sharks. Hang your heads in shame, Colin Farrell, Jennifer Aniston and, uh, Kevin Spacey in Horrible Bosses! Ha ha!

Then when Goforth bumps into Etti and he drops a tray (this is presumably to make her look bad, although frankly Etti just looks like a klutz) she yells, “Shit on your mother!” This was groundbreaking stuff, as the ‘S’ word had never been uttered in a major Hollywood release before. How thrillingly transgressive! Hard to believe audiences didn’t flock to see this one.

Then we get a long scene between Goforth and Miss Black, during which they exchange dialogue that I can only presume was meant, in some manner, to be droll or sophisticated or clever or some damn thing. The horrible part is that the film already feels like it’s treading water only 23 minutes in, with an hour and a half left to go. And this was the age before extended end credits, remember, so there really an hour and a half remaining.

The big upshot is that Goforth is musing over whether to take Chris as a lover. “What do you mean by a lover?” Miss Black, a grown woman, asks in reply. That’s the sort of dialogue we’re getting here. Then Miss Black explains that her only ‘lover’ was her husband, Charles, who died last spring. Really, that never came up before? “Beats me how you could have a husband named Charles and not call him Charlie,” Goforth responds. That, too, is an example of dialogue that Mr. Williams apparently couldn’t bear to cut. You just can’t lose gold like that, baby.

Miss Black, or Blackie, as Goforth calls her, mentions that Chris’ only clothes were demolished in the dog attack. Luckily, Ms. Goforth maintains an entire wardrobe full of horribly gaudy men’s robes. She grabs a patterned black one (black being, as we’ve seen, Chris’ color), which she describes as the “robe of a Japanese warrior.” Sure, why not. Luckily, there’s even a sheaved katana sitting nearby (?) to complete the ensemble. She also tells Blackie to wire a dinner invitation to “the Witch of Capri.” Seriously.

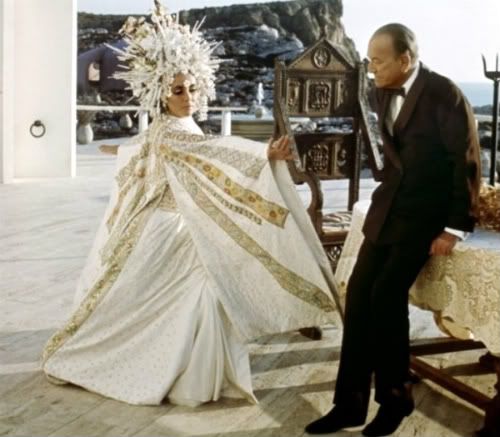

The Witch proves to be an exaggerated poof (a woman in the play, not that it matters much) played by an aged, tuxedoed *gack* Noel Coward. Refusing to strive with the Sultans of Ham, Coward instead delivers a rather restrained rendition favoring an archly catty tone. This proved a wise strategy, as Coward received some of the only good notices attached to the film. Yet even those, I suspect, may have been influenced by respect for a veteran trooper gamely facing an impossible situation.

“Can’t…move…under…weight…of…robes….”

In a typically nonsensical touch, the Witch is born from the beach sitting atop a brawny man’s shoulders. “The bitch would have me over here at high tide,” the Witch ‘drolly’ sniffs, “so that I should get up there looking like a piece of seaweed.” One can only assume Mr. Coward lost some sort of playwright bet with Williams, with the loser having to appear in the film adaptation of the winner’s worst play. If so, it was a sucker bet. I can’t imagine Coward ever wrote anything half this bad.

Goforth appears in a robe and with what appears to be a gigantic sea anomie as a hat. Seriously, it’s the sort of thing a Mu princess in a Japanese sci-fi film would wear. Blackie, meanwhile, suddenly has her hair down and is wearing a knee-length skirt. Previously she wore her hair pulled back in a tight bun and favored mannish slacks. Presumably the idea is that her femininity is blossoming do to Chris’ ur-masculine presence on the scene.

Ms. Goforth is annoyed to find the table set for three, as Blackie has presumed to have a plate set for Chris. I know Goforth is meant to be a horrendous shrew, but Blackie instead just comes across as grossly incompetent and insolent. I mean, really, is that her decision to make? I wonder what Ms. Taylor’s reaction would have been in real life had her own personal assistant done the same thing.

Goforth and the approaching Witch (that’s all he’s called, and Coward’s credited as “Witch of Capri”) greet each other by shouting a yodel-like “Yaaaa-hoooo!” back and forth a few times. Really. And so begins a pointlessly, not to mention excruciatingly, long scene of Sissy and the Witch having dinner, a sequence which runs roughly several hours. During this, the pair engages in badinage of the sort that might strike the participants as hilarious and supremely witty when in their cups, but proves downright embarrassing in the sober light of day. Coyote Ugly Banter, pretty much.

Indeed, Taylor actually seems drunk at times, enough to make you wonder if she was indulging in a spot of method acting, as it were. And some of the lines are so lame that I wondered if they let Mr. Coward and Ms. Taylor attempt to ad lib somewhat. If so, it was a really bad…. You know, I can’t really say anything Williams might have written would have been any better, so never mind.

The odd thing is that Mr. Coward was exactly the sort of fellow he so poorly plays here, a perennial party guest and renowned raconteur who probably had dined with Ms. Taylor in quite a similar fashion. Yet despite basically playing himself, he (literally) just doesn’t bring much to the table. He’s as convincing as himself here as Bob Hope was playing himself hosting the Academy Awards in The Oscar. In each case you get the idea the guy was saving his good material for real life.

With the film’s editor presumably locked away in a closet, beating at the door and all “For the love of God, Montresor!,” the scene is allowed to drag on for an unconscionable stretch of time. I can only theorize that this is because it was a long sequence in the play, and because they needed to somehow justify both Mr. Coward’s presence and his third billing in the credits. In any case, the heart swells with pity when reflecting on those unlucky few who were forced to sit through this in a theater. You can only go up to buy popcorn or hit the washrooms so many times. And you come back after loitering as long as you can, only to discover the exact same scene is still running.

Liberace and Prince agreed that this outfit was “a little over the top.”

I probably haven’t mentioned it enough, but they are always careful to have Goforth go into a sudden coughing jag, or swoon or bit or something like that. I think they had a quota of one such incident in each scene. This is to remind us, flagging attention or no, that Goforth is in Dire Health. So consider that aspect of things stipulated to until they play it harder later in the picture.

Among the Dinner Scene highlights:

- Goforth does her impression of a kabuki dancer. Let’s just say that she won’t be winning America’s Got Talent or anything.

- The Witch reacts with eyebrow-arching horror when a whole Monkfish is brought to the table. Because, you know, you’d never have seen one of those in an upscale restaurant in Capri. He also turns down a plate of gull’s eggs. I think it’s supposed to be amusing what crazy things Rich People eat.

- Two live sitar players are on hand throughout much of the scene. I think you can imagine how much that adds to things.

- Hearing that people are gossiping about her elaborate intercom system (really), Goforth acidly spits, “Capri has turned into a nest of vipers, and the seas is full of medusas [as in jellyfish; one had stung the Witch earlier in the day], and the medusas are spawned by the witches, male and female, the kind that have little forked tongues in their mouths like lizards.” That’s one of the better bits. Pretty much ten straight minutes of stuff like that.

- Goforth offhandedly mentions that during the Salad Days with her Young Poet, they would wear Samurai robes. Which is what she selected for Chris to wear! Wow. Did I just blow your mind?

- Uhhh….

Anyway, like World War II, the scene eventually ends. In a fashion, anyway. The real reason for the dinner invite is that Goforth wants to pump inveterate gossip the Witch for the lowdown on Chris. She’s struck by the fact that at the exact moment she was describing to Blackie the mountain climbing Young Poet who was the Love of Her Life, “another poet* climbed a mountain to see me.” Wow, yeah, makes you think.

[*Not a particularly young one, though.]

“Christopher Flanders!” the Witch replies, “Well, God help you, Sissy.” (Ah, he’s seen some of Burton’s other movies, then.) It seems that Chris has among her crowd the “unfortunate reputation of calling on a lady just a step ahead of the undertaker.” This has occurred with such regularly, in fact, that Chris has earned the sobriquet “the Angel of Death.” (Apparently several people had seen Burton’s other movies.)

The news visibly unnerves Goforth, setting off an intense psychic struggle in which her fears of Chris’ macabre reputation war with her lust for him, a stunningly profound battle of Eros and Thanatos that reveals so much, perhaps too much, about the human condition. Deep stuff, ya know.

Anyhoo, the scene continues as the two make their way into the Pink Villa to check on Chris. Apparently when in danger of being kicked out by one of his hosts, he has a habit of OD’ing on sleeping pills. He always makes sure he’ll be found before he actually shuffles off this mortal coil, though. In this case, a quick examination shows that currently he’s just sleeping regularly.

Sitting at the foot of Chris’ prodigious bed, under a ridiculous dreamscape mural on the ceiling, Goforth and the Witch continue to yak. The Witch relates a charming anecdote about a fellow gay sophisticate who wards off the wafting scent of young ladies’ privates by holding a vial of ammonia under his nose and yelling, “Poisson!” The Witch concludes this wry tale by noting, “Personally, I’ve always found girls to be fragrant in any phase of the moon.”

The actors looked for anything that might distract the audience from them.

Yep, that’s the sort of surefire, audience-pleasing material that secured Taylor and Burton a cool million dollar paycheck each, back when that was insanely big money. And I use the word ‘insanely’ advisedly. Anyway, I can only assume this current dialogue was recited back at the dinner table in the stage production. Perhaps somebody occasionally reminded Losey that since it was a movie the characters could “move around,” and so they relocated the actors here, albeit not to much effect.

The scene ends with a bizarre little montage, accompanied by portentous music alerting us that we are now witnessing a Dark Night of the Soul. We see the Doctor, liquor bottle at hand (because he’s a Drunk; that’s his character, you know) looking grimly at what is obviously a blood sample taken from Ms. Goforth. Meanwhile, he’s being intercommed by Goforth, who lies moaning in her bed.

Cut outside to the Witch staggering around in the dark, yelling “Yaaaa-hoooo? Sissy?” in what I’m sure they hoped would seem like a Lear-like manner. Frightened by…I don’t know, Fate, maybe, or something Equally Profound, the Witch returns to Chris’ villa, waking him. “Sissy! She’s disappeared!” he cries, then starts making “WOOO-WOOO!” train sounds. Really, that happens.

Chris, unsurprisingly, responds by making a quick exit. He does stop to don his robe and grab his katana though. I’m sure each and every little touch here Means Something, but I apparently I’m too much of a philistine to figure out what. To me it all seems like horsecrap.

More little snippets. The doctor hooks Goforth up to an IV. Chris wanders around in the dark. (You’re not the only one, bud.) We see a shot of Goforth as reflected in a mirror. As we learned in The Oscar, such shots are the very height of artistic something or other. “Pain gone ‘til tomorrow,” Goforth sighs. I wish! There’s still an hour and 13 minutes of this thing left. Where’s my IV, damn you?!

Outside Chris blinks in the sudden intense glare of a flashlight. At the other end is Rudi the Sadistic Majordomo—what a better movie that would be!—and his dogs, patrolling. Rudi takes advantage of the situation by hitting Chris in the stomach with his torch. (Add Michael Dunn to the list of people who had seen other Richard Burton movies.) “You want some more of that, do you?” Rudi sneers to the gagging poet. Well, this is shaping up nicely!

To my horror, however, Chris is then saved by the most importune appearance of Miss Black, who chastises Rudi and hauls Chris off. What a tragedy! Seeing Richard Burton being pummeled by a dwarf would have been the single greatest thing I, or anyone, really, would ever see in the history of humanity. Roy Batty would have spoken of it in his death speech. Damn you for taking that away from us, Miss Black! Damn you!

Blackie takes Chris back to her chambers, a blue analogue to the Pink Villa. The whole situation is fraught with *cough, cough* sexual tension. Miss Black is jittery, and blurts out that “Last spring I lost my husband.” Well, that was careless of you. Chris, for her own good mind you, grabs her face and leans in for a smooch.

Pulling back, he says, “I’m going to do two simple things for you; put this picture of your husband in a drawer, and put your sleeping pills in the drawer.” Hey, pass those over here, buddy! I could use them! (Just kidding. This film is soporific enough for anyone.)

Then he begins to brush her hair. “I think you’re taking unfair advantage,” she gasps. I know! All those miserable souls, dozens and dozens of them across the nation, stuck in a theater after actually paying to see this crap! How did that guy live with himself? Quick, somebody get Rudi and his flashlight! (Another movie that would have been better than this one.)

Anyway, Chris in just on the verge of getting a little something-something when Goforth’s voice booms out of the intercom. Burtonus Interruptus, thank goodness. “She wants to give me dictation,” Blackie explains. From Chris’ annoyed expression, Goforth isn’t the only one.

In any case, Goforth has wakened and finds herself moved to dictate her increasingly fevered memories of the death of her first tycoon husband, Harlan Goforth. He, I am entirely horrified to report, died in the saddle as it were, and we get to hear all about it in what is the single most gawdawful monologue I’ve ever heard in my life.

Harlan was, of course, a munitions manufacturer (the “king” of them, in fact), because that’s the most obviously EEEEE-vil sort of tycoon. Who are bad to start with, not like Young Poets; and also because it again conflates Death and Sex in a way that might strikes the intellectually nearsighted as perhaps ‘meaning something.’

As you’d expect, subtlety not only goes out the window, but rockets out on a jetpack. Harlan was “a warlord, who monarchs and presidents placed next to their wives at banquets.” He was also fat, of course, like all Plutocrats. (It’s not mentioned whether he was wearing his top hat, monocle and spats during all this, but I think we must assume he was.) Sissy, meanwhile, was “scarcely more than a child,” so that he “is crushing me under the awful weight of his body,” as Our Protagonist cries out.

It’s an extended scene, probably the centerpiece of the stage version, and includes a bit where the writhing Liz, legs splayed (at least she’s gowned!), reenacts the carnal apocalypse. “He mounts me again! He mounts me!” she cries in horror several times. Remember, she didn’t know Love until her Young Poet, so all her previous sex was of the degrading kind, I guess. Much like this scene.

I must admit, I have never cared for the ‘50s style of big, method acting Ms. Taylor was addicted to in this era. Camp fans—a distinct set from the Bad Movie buffs, albeit with some overlap—dig it totally, probably for the exact reasons it doesn’t work for me, particularly its exaggerated, high wire artificiality. Admittedly, such ‘method’ acting was a reaction to the overly minimalist, “I say, old man, did that tiger just tear my arm off?” style of your David Manners and Leslie Howards. Even so, I have never gleaned much from the twitchy antics of the James Dean / Montgomery Clift crowd.

Burton is another matter. That guy’s acting was SO big that it’s fascinating, that rich, deep plummy voice alone downright hypnotic. When he was in a terrifically bad movie, as he so very often was, he always seemed determined to out-bad it. And generally, he succeeded. Burton could give a great performance, but only (I’m guessing) if he had a director who would really sit on him, and focus that intensity like a laser. Burton had a taste for throwing the throttle wide open though, and then slam it wide open again twice over just for emphasis’ sake, like Quint in Jaws. Actually, quite a bit like Quint in Jaws. And so as his career progressed and his power grew he chose more and more films that let him do just that.

Ms. Taylor did the same thing, albeit one thinks she was actually trying to give ‘great performances.’ It seldom seems the sort of lark it always appeared to be for her hubbie. And whatever preternaturally bombastic thing Burton had—honed moreover by years and years on the British stage, projecting out to the cheap seats—Liz didn’t. To be fair, almost no one else ever has. Charles Laughton, maybe. Not too many others.

You hear the phrase “a fearless performance” a lot. Too much, surely. This here, though, is a fearless performance. Taylor really throws herself into the scene, holding nothing back; certainly not dignity. Sadly, Williams leaves her out to dry. The monologue is HORRIBLE. There’s a reason people aren’t often fearless, and it’s because being that way can get you killed. And Taylor dies a truly gruesome death before our eyes, expiring slowly over the course of nearly five straight minutes, which is a boatload of screen time. I vastly admire her courage and dedication, but the cause was not worthy of her.

For her pains Taylor ends up humiliated in a way Burton never could be, because for him being Big seemed the goal in itself. Taylor again is clearly trying to act here, but no amount of histrionics, no matter how brave, can redeem Williams’ ghastly writing. It’s your classic train wreck. Burton is a man who lured a woman into the hard stuff, which eventually kills her while he walks away unscathed. Usually we’re talking booze or drugs (although there was plenty of that for them, too), here it’s this consuming style of acting. I never felt sorry for Burton, ever, because he never lost control of what he was doing. However, I literally cringed for Ms. Taylor watching this sequence.

The movie isn’t helping her either. One of the conceits, never really explained, is that Goforth’s intercommed communiqués are broadcast through the entire estate. We see Rudi (lying in bed in a robe, a few of his beloved dogs panting nearby) smirk at the recital. Etti, playing cards with a few of the other servants, reacts to it with evident, literally eye-rolling boredom. Meanwhile, Blackie listens in increasing horror until she is driven to seek out her mistress and save Goforth from herself. It’s like a very short play entitled, “Three Appropriate Audience Reactions to The Worst Performance in History.”

Anyhoo, Harlan died with “terror in his eyes,” and clearly this experience is what feeds Sissy’s fears of her own impending demise. Because things like that are more relatable when there’s a clear-cut explanation for them. The recollection sends her into a panic mirroring her original one during the actual death. She throws open the door and runs outside to the balustrade, and I guess (from the approaching Blackie’s reaction) is in danger of going over the edge—literally, I mean—although this doesn’t really come across otherwise. Anyway, it all finally wraps up, although this would be more of a relief if there weren’t over an hour of movie left.

Soon the Night of Our Mutual Shame has passed, breaking into…the Day of Further Mutual Shame. Blackie returns to the Blue Villa, where Chris is still waiting for her. She tries to run, but he grabs her. “Everything you say or do is like you’re playing a game!” she accuses. Yeah, on the audience. Anyway, I guess they do it, although thankfully off camera. (Burton was making a movie with his wife, after all.)

Outside Goforth is on the balcony, basking in the rejuvenating sunlight. Actually, we open the shot with another close-up of her gigantic diamond ring. It’s like some weird fetish picture for gem enthusiasts. By the way, if a sports car means a man has a small penis, what does that ring mean? In any case, I’d be downright terrified to be wearing that thing, as Taylor is now, while standing over a cliff side. I’d be so scared it would slip off that I’d have superglued it to my finger.

And…more stuff. For the sake of Pete, I just can’t go over all of it. Besides, we’ve now officially entered the dreaded Treading Water portion of the film. This is where they basically just fine tune stuff we’ve already seen until the proper point in time at which we can start moving towards the climax. Goforth dictates more of her memoir. She yells at everyone. She smashes more stuff. She coughs and swoons. She babbles portentously about “the Meaning of Life” and other such weighty manners.

Elizabeth Taylor muses on how Boom! might be the greatest movie she ever made.

Some of her lines are inadvertently amusing, however. “What the hell are we doing?” Goforth muses. “Going from one goddammed frantic distraction to another. ’Til finally one too many goddammned frantic distractions leads to…disaster.” Hmm, sounds like she’s reflecting on the movies she and Burton had been making for the last five years. Of course, she’s wrong in one respect. Disaster wasn’t a single, ultimate byproduct of the process. No, Liz and Dick left disasters strewn in their wake like breadcrumbs.

For his part, Chris continues to lurk about, mooching food off Goforth whilst trying to avoid her attention. Blackie aids him in his scavenging, because if your boss is mean it’s OK to steal from them, particularly if they’re rich. However, he eventually comes out of hiding; I guess for some more serious gold-digging, now that he’s nailed Blackie.

Now get finally the first scene to feature Taylor and Burton together. This seems odd, given that the film’s nearly half over. (Of course, that still leaves us roughly an eternity to go.) You might think they’d give the big meeting of the two main characters some sort of build-up, but there’s none, really. It’s almost like both actors ended up on the balcony by sheerest chance and decided to do a scene for the heck of it.

Because they have nothing better to do, they go back over the dog attack again. Chris mentions it (“Their bites were worse than their barks,” he says; get it); Goforth make ‘sly’ reference to the covertly installed new signs mentioning the dogs; Blackie ‘blows’ her boss’ scam by announcing that said signage has just gone up. Goforth, of course, is livid, although naturally she doesn’t just fire Blackie either.

I assume Blackie is meant to be the audience’s identification figure and—maybe, who can tell with this thing?—the film’s moral center. However, it’s hard to get past her constant screwing over and badmouthing of her employer. If the job is so unpleasant she should quit. If not, she should show a little loyalty. Moreover, I’m not really sympathetic to Chris’ case here. He knowingly trespassed, and frankly Goforth could have just had him shot for all I care. And what’s the point of having guard dogs if they can’t guard anything?

Goforth’s fear of getting sued by Chris might be realistic, which of course this particular movie is obsessed with being, *cough, cough*, but it sure is dull. Again, the overarching question is ‘Why is this damn thing so long,’ and the answer apparently is, “Because what could possibly be cut?” I don’t know, this whole scene, for instance? (The real answer: “Because this is an Important Movie, and thus must have a Lot of Stuff in it.”)

My favorite part is when Blackie, defending her new *ick* lover, reports to Goforth that Chris was accosted the night before by Rudi. In other words, that he was set upon and trounced by a dwarf. Nobody seems to be aware of the comic side of this, which I guess sums up the movie as a whole.

All but sobbing by this point, Blackie is starting to come across not as merely emotionally damaged, but mentally challenged. She literally acts like a 12 year-old arguing with her mom, which is kind of hard to take from a grown woman. And it makes Chris look even sleazier than maybe they intended. Given Blackie’s level of maturity his seduction of her is starting to take on a sort of child molester-y vibe. Chiding a grown woman into sex is one thing, taking advantage of someone with the mind of a child is another.

Blackie flees, again much like a 12 year-old girl. Presumably she will run to her room, there to flop upon her bed and write in her diary (an object surely festooned with unicorn and Twilight stickers) about how mean Ms. Goforth is. Meanwhile, Chris writes out a statement admitting he knowingly trespassed, which serves to both placate the ruffled Goforth and start ingratiating him with her. He also helps her swill down a pill with a shot of booze. Mommy’s little helper, he is.

Settled down, Goforth apologizes / spills her guts to Blackie in an echo-y fashion over what is, I am absolutely certain, an early prototype of the Mr. Microphone. She gives another whole monologue (ye gods!) via this instrument, which at least shows they haven’t run out of ways to make the movie yet more ridiculous.

“Hey, good looking, I’ll be back to pick you up later!”

This accomplished, we get another scene (finally!) between our Stars. It’s about time since, barring some unbeknownst contingent of rabid Joanna Shimkus fans, they are ones who attracted what few ticket buyers the film garnered. However, their conversation is so banal and insipid that’s hard to believe it’s scripted. On the other hand, if his intention was to create two monumentally boring dullards, then Williams was a far greater playwright than he was ever given credit for.

Goforth, after Chris’ samurai robe shifts in the wind: “You have a good pair of legs on you…I mean, under you.”

Chris: “I find them very useful for climbing mountains.”

Goforth: “Good teeth, too.”

Chris, looking to mooch some breakfast: “I’d love to sink them into some hot buttered toast.”

Scintillating stuff, eh? Still, if you’ve ever wondered what it would be like to see Richard Burton ask for a cup of coffee with cream and sugar, only to be told there is no cream and only Saccharin tablets, well, then your oddly specific dreams have finally been answered.

The action, as it were, proceeds in a like fashion for a long stretch, as the two trade odd, shallow little observations and epigrams: “The chopping of a head is a sure cure for a tongue that’s too big for a mouth!” Seriously, somebody wrote this stuff? Presumably these exchanges are supposed to allow us to peer God-like into their souls. Sadly, however, their souls prove to be as flatly uninteresting as the rest of them. Then, after a while, they are rejoined by the Witch. Seriously, fifty more minutes of this? Yikes. This movie should come with a glass case containing a killer bear and a sign reading “Break Open in Case of Tedium.”

I apologize. Other than transcribing more dialogue, there’s not much meat here. I mean, it’s all pretty appalling, but in a “you have to see it” way. The biggest character moment comes when Goforth goes in the house, and the Witch tries to get Chris to leave before yet another woman dies on his hands and further besmirches his reputation. (The Witch’s motive, I guess, is that he wants Chris to join him in Capri and be his lover.) However, it appears Chris sees it was his task to minister to such women, and he refuses to go. When the Witch continues to press, Chris stands his ground:

Chris “Don’t make me say things about you that I’d rather not say.”

The Witch: “What could you say about me that hasn’t been said?”

Chris: “You’re the heart of a world that has no heart, the heartless world that you live in.”

Well, you can’t argue with that.

The Witch presses his suit, but is interrupted by Goforth, who apparently has decided to stake a claim to Chris after all. She comes to sharply tell the Witch that his boat back to Capri is waiting. And so we bid adieu to Noel Coward, who is heading off to a better place. I don’t know exactly where he’s going, but really, pretty much anywhere has got to be better than this.

More stuff with Goforth and Chris. Just…more. At one point we seem to be watching short segments of scenes that have otherwise been excised. For instance, suddenly Goforth and Chris are in a suspended gondola cable car used to ferry people to the beach far below. And I mean just that; there’s a cut and there we find them, seemingly mid-scene. Goforth is in the middle of a panic attack (for which Chris mocks her) because she has a fear of heights. What the hell was she doing in the thing, then? We’ll never know. I’m not complaining, mind you. It’s not like anything in this movie makes more sense when you see the whole scenes, and at least this way it’s shorter.

Down at the beach Chris goes for a nude swim. Luckily for us we see this from a pretty good distance, although I imagine it’s a body double, even so. Goforth, who’s been in one of her fugues, comes to and reacts like any of us would. “Put on your robe!” she screams hotly. “Put your clothes on!” Hear, hear.

More stuff. Ever more stuff. More yakking, more sound and fury signifying nothing. (They provide the sound, I the fury.) Later we see Goforth gussying herself up, allowing for another mirror shot. ART! Is she ready to bed Chris yet? Maybe, but in the background we see a smirking Rudi. He approaches to hand her a small, pearl-handled revolver, one mentioned in an earlier anecdote. At this point I began hoping her intention was to shoot Chris. Or herself. Or Tennessee Williams, or Joseph Losey. Or me, really. Anything to end this.

Probably not, though. 42 minutes left. Plus, I’m pretty sure those are dog minutes. So that’s about five hours in human minutes.

As things slooooowly drag forward, we see increasing signs of Sissy’s degrading health. Meanwhile, every once in a while Chris will pause stock still and softly mutter, “Boom!” And yes, he’s still wearing his samurai robe, carrying his katana. I suppose this is supposed to symbolize his absolute fealty to Goforth,

despite her (quite justified) paranoia about him.

Most obviously, he keeps trying to drag her to the edge of the cliff she’s (rightly) so terrified of. When she responds with hysterics to his tugging at her, he serially pooh-poohs her fears as unreasoning. Yes, because there’s little to fear from standing alongside a great abyss on a windswept island, especially if one is given to fainting spells.

Of course, the idea—or rather, THE IDEA!—is that her ‘childish’ fear of heights is but a SUPER SUBTLE AWESOMELY BRAVURA METAPHOR FOR HER FEAR OF HER IMPENDING DEATH. Wow! Super cool keen! And acting in his already assigned role as the “Angel of Death,” Chris is trying to help her overcome her trepidation regarding this inevitable fate, and allow her to pass on in peace. (Oh, uh…SPOILERS. Sorry, a little late, I guess.)

So…now that we’ve gotten that, can we just go ahead and end the picture? No? We have to watch these preordained things play out at length? *grumble, grumble, grumble*

Sadly, however, we’re now further ahead of things than the movie is. Anyway, Goforth eventually lays down her cards and agrees to let Chris become her gigolo, which she assumes has been his goal from the start. When he attempts to demur from that accusation, she spits, “Oh, don’t give me that moral blackmail!” Which, I mean, who wouldn’t say that? Further inane and incomprehensible dialogue follows. And follows. And follows.

Amid the blather we shift out a few more rather weak ‘revelations.’ The fisherman who was killed, as referenced earlier, was *gasp* Goforth’s lover, albeit one whom she maintains she caught attempting to steal her gigantic ring. (I’m guessing he developed a hernia from trying to lug it around and plummeted down the mountain as a result.) After she admits this, Chris reacts to the sound of the pounding surf by again saying “Boom!”

Goforth: “’Boom’?”

Chris, leaning his face towards hers: “Boom! The shock of each moment, of still being alive!”

I must disagree with my poet friend, I fear. Frankly, my own shock occurred at each moment of still being awake. Maybe I’ll say “Boom!” after the movie’s finally over, because then, yes, I will no doubt be shocked to discover I am still alive.

And yep, that right there was the line that was so incredibly awesome they decided to name the movie after it.

By the way, perhaps you’re starting to curse about the length of this review. Well, let me tell you, I’m skipping over plenty of stuff. Believe it or not, you’re getting treated to the kid’s meal version here. For instance, there’s a whole thing where Goforth starts to panic after Chris gets a call regarding yet another woman at death’s door and considers leaving to go succor her, instead. Or when conversely Goforth begins thinking Chris is there to kill her, and has Chris’ bags brought and dumped out on the floor before her. That’s like of ten minutes of screen time right there. I could have written a whole other page or two about those scenes.

“C’mon, somebody‘s got to know what’s going on in this screwball picture!”

But no, I spared you all that. Try a mile looking through my eyeglasses before tossing around the invectives, Jack.

But yeah, maybe it’s time to move things along here:

- In Chris’ bags (see above), Goforth finds his address book. It’s filled with the names of now-deceased rich ladies. Bum bum bum.

- During this search, Michael Dunn is prancing around in his little pseudo-Nazi uniform, leering as he jabs his gun at the patently innocuous Chris. The film does evoke musings on tragedy, but mostly the tragedy of a fine actor stifled by physical realities, who took this nothing part in this crappy (if high profile) picture and probably was glad for the work. Meanwhile, Burton and Taylor, superstars who blithely squandered the opportunity to make films worthy of their talents again and again and again, just sit around per usual satisfying their juvenile appetite for chewing the scenery.

- So Goforth finally asks Chris to stay. “We all of us invite Death, Mr. Flanders.” Career death, maybe. Then she immediately has another blind spell, provoking further reams of inane ‘arty’ dialogue. Then they finally kiss. Wow, what a payoff. Now it’s all worthwhile.

- Fear of heights / worsening health attacks / mean or paranoid treatment of the staff…rinse and repeat as necessary. And apparently it was VERY necessary.

- I have to say, though, while Goforth registers as cartoonish more than Epically Unlikeable or Bravely Sympathetic (her two assigned, alternating character tones), Blackie continues to come off entirely as a shrill, nagging, self-righteous little asshole. I keep assuming she’s supposed to be the film’s ‘conscience’ or something, but man, they really bolloxed it up if that was their intent.

- Hey, Chris just said “Boom” again! Wow!

- Why does the film assign the ‘richest woman in the world’ a doctor sporting a comic opera Italian accent? Was the part written for Chico Marx or something?

- “You were so fascinating in your samurai warrior’s robe that I forgot Time was imprudent.” WTF? I hope Williams wrote better than that for his other plays.

- Chris is invited into Goforth’s bedchamber. Cut away, cut away, cut away…for the love of all that’s holy, CUT AWAY.

- But no, we instead are subjected to the horrors of…more yakking. It’s a dilemma, all right. Neither will SHUT THE HELL UP, but it’s not like we really want to see them make with the kissy face, either.

- Heroically, rather than following her to bed, Chris instead expresses a moment of umbrage over Goforth’s earlier mistreatment of him and stalks off. Don’t worry, though, Goforth staggers after him, ensuring there will not be much lapsing into silence during the film’s final 16 minutes.

- SHUT UP SHUT UP SHUT UP SHUT UP SHUT UP……….

- This is the *cough* virtuoso, tour de force climax, I guess, the final eleven minutes (thank heavens!) where Chris finally forces Goforth to come to terms with Oblivion. Much like everyone involved in the film had to when the meager box offices receipts and vitriolic notices starting coming in. The film was originally budgeted at just under four million dollars, but ended up costing ten million (!). US rentals amounted to two million, of which the studio would have seen about half. As for the critical reaction…see below.

- SPOILERS. Be warned.

- As you’d expect, there’s really only one way this can go; Goforth expires, while Chris helps her accept her fate with peace and grace. In one of the film’s rare good choices, Taylor and Burton actually tone down the acting a couple of notches. Too little too late, but better than the even more exaggerated thesping I’d been expecting from the two.

- “This has been the most awful day of my life,” Goforth says at one point. Lady, I know exactly how you feel.

- She also says she plans to “go forth” several times, lest we had missed the symbolic significance of her name.

- With our climax patently locked in, and presumably thinking the audience would be looking for some kind of ‘point’ to the whole thing, they apparently decided that what was really mesmerizing us was the issue of Chris’ motives. So as the prostrate Goforth slides restfully into the afterlife, Chris relates at some length the tale of how he helped his first person to a longed-for demise, and how afterward “a great Indian teacher” told him that these deathbed ministries were his destiny. Thus, oddly, Goforth’s death scene is actually Burton’s big moment, not Taylor’s. Another idiosyncratic choice.

Sissy Goforth finally expires, about two hours after the movie does.

- As Chris tells his story, though, he also systematically removes all of Goforth’s jewelry, paying special attention to her gigantic ring. So, saint or sinner? Frankly, for such a crazy film, this seems an oddly prosaic question to end things with.

- Even so, this is the horse they bet on, and they drag it out. Chris leaves Goforth’s body lying on her bed and heads out onto the balcony with a glass, a bottle of wine, and the Giant Diamond Ring. Gasp! Does he intend to steal this fabulous treasure? But no, with a chuckle he drops it nonchalantly into his wine glass and tosses it and the Ring over the cliff. And…that’s pretty much it. The End. Wow, it sure was worth it all in the end.

- Plus, you know, he did actually steal the ring, and from a dead woman to boot. However, it was to throw it away rather than to sell it. So, I guess that’s supposed to be OK, then.

- It amuses me to think that James Cameron stole the ending of Boom! for Titanic, even to the extent of both of the jewelry-chucking characters being utterly selfish assholes. Both seem completely happy to toss a gigantic fortune—which surely could be put to better purposes—to the bottom of the sea. Because, you see, their whims are all that matter. Sure, each of them stole the fabulous object they so consigned. But, you know, they were just acting on their feelings, and what’s more important than that?

- Boom. The shock of realizing that this freakin’ movie is finally over.

They devour life, all right. Two hours at a time.

AFTERWARD:

Editorial Note: First of all, I exhort everyone to buy a copy of Harry & Michael Medved’s The Hollywood Hall of Shame, a simply brilliant book filled with tons of original reporting on the making of an array of legendary cinematic bombs. It’s an essential read, and their chapter on the production of Boom! (one of several Liz Taylor fiascos they autopsy) is fascinating material. It’s one of the two or three truly essential books on filmmaking gone awry, right up there with The Devil’s Candy by Julie Salamon. You can find tons of copies of both books on www.fetchbook.info that even with shipping will set you back five bucks or less.

Among the various stumbling blocks this film faced (such as the fact that the play it adapted both sucked and was already an established abject commercial and critical failure on the stage), a major one is the big name stars whose interest presumably got the movie into production. Even putting aside how garishly awful Taylor and Burton are here, on a level that few other actors were even capable of touching—Burton is the Michael Jordan of Bad Acting—the fact remains that they were just horribly miscast.

Flora Goforth is meant to be a woman nearing the end of a long life, one bitterly fighting her impending death. Chris, the mythical Angel of Death who arrives to ease her way into the afterlife, is meant to be a veritable Adonis whose youth and abject beauty calls to Flora’s mind the *snigger* “young poet” who was her one, true love. Remember that incredibly handsome Angel of Death the young Robert Redford played on The Twilight Zone, the one who appears to an old woman who bitterly fights her impending death, to ease her way into….HEY!!!

That aside—Williams certainly paid the price for any cribbing from an old TV show he might have done—the age-appropriate stars of the 1964 staging (the one that ran five performances) consisted of the 62 year-old Broadway legend Tallulah Bankhead, who might well have been made up to look even older, and the 33 year-old Tab Hunter. And yes, that’s right. By 1968 former British stage wunderkind Richard Burton was assaying roles previously played by Tab Hunter. Mull on that.*

[*And he was paid a 1.25 million bucks to do so! $1.25 million in 1968 dollars, to boot.]

At the time the film adaptation was made, Ms. Taylor was 36. Mr. Burton, for his part, was a rather dissipated-looking 43. In other words, rather than seeming to be 30-plus years younger than Goforth, Burton’s Chris looks about a decade older. Patently middle-aged, Burton doesn’t suggest someone ‘young,’ poet or otherwise. This aspect alone throws the whole project off kilter.

Meanwhile, despite having even then a history of real life health scares—she nearly died during the filming of Cleopatra, for instance—Ms. Taylor is entirely too young to suggest someone who’s been married six times and is nearing the end of a lengthy life. At best, Ms. Taylor’s Goforth is a woman whose impending death is an all too early one. This tosses the play’s central conceit right out the window. Why wouldn’t Goforth rail against death, coming so early in her life as it is? I guess we’re meant to be as blinded by the couple’s purported star power as apparently they themselves were. Few were, however.

So what drew the couple to the film? Well, they had been on at least a bit of a roll at that moment. Taylor and Burton had starred in their most acclaimed film together, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, two years earlier. The year after that they starred in the only other movie they made together that didn’t suck, an adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew.

Clearly stage play adaptations were working for them. Given this, it’s perhaps natural that Taylor sought to again work with Tennessee Williams, the playwright who earlier in her career supplied the basis for a pair of films that provided two of her biggest hits, not to mention back to back Best Actress nominations.

Ms. Liz’s history with Williams extended back to the halcyon day before Burton (and Jabootu) got his mitts on her. She had starred in two highly successful adaptions of his more popular plays, Cat on the Hot Tin Roof and Suddenly Last Summer, about a decade earlier. However, by 1968 Williams’ small stockpile of great and even decent plays had already been exhausted—Streetcar Named Desire had come to the screen back in 1951, Baby Doll in 1956, Sweet Bird of Youth in 1962—and this mutual quest for a return to the salad days reeked on both their parts as more desperation than inspiration.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, Ms. Taylor was the spouse most interested in the project. This may be further deduced from the fact that she is clearly the star of the piece, with Burton assaying more of a supporting role. As well, she enjoyed hanging out with Williams, who was an on-set presence due to his writing the script. (Conversely, Williams had nothing to do with the screenplay for Night of the Iguana, Burton’s previous—and rather more successful—adaptation of a Williams play.)

[*Ms. Taylor had a longstanding tendency to be drawn to the emotionally unstable, including her famous friendships with Montgomery Clift, Michael Jackson and the elderly Marlon Brando. Williams fit pretty comfortably within that ass menagerie.]

For his part, Burton was apparently not nearly as enamored with the playwright’s company. With his best days far behind him both personally and professionally, a situation exacerbated by his chronic drug use, the increasingly unstable Williams reportedly rankled Burton quite fiercely.

Ms. Taylor’s mounting professional fears were justified. At this point of things her career was starting to feel the strain of both her inevitably increasing age—nearly always more dangerous to an actress

than an actor—and the string of flops she’d had beginning with Cleopatra. Even the partial career recovery represented by The Taming of the Shrew and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? had come to an abrupt end via another pair of Taylor/Burton fiascoes, Doctor Faustus and The Comedians, the films the couple made immediately before Boom!

Meanwhile, age wasn’t the danger to Burton it was to Ms. Taylor. He also benefited from several successful Taylor-free pictures during this period. Following Cleopatra Burton starred in Beckett, one of his definitive screen roles and a big hit; had another sizable success with Night of the Iguana; and starred in the superlative Cold War espionage drama The Spy Who Came In From the Cold, in which Burton is downright brilliant and for which he garnered a Best Actor nomination. Even after Boom! he bounced back handily by next starring with Clint Eastwood in Where Eagles Dare, a sizable WWII action flick that proved Burton’s single greatest moneymaker.

So Burton not only several recent financial and critical hits on his resume, but producers had noticed that he had a much greater percentage of success with films where he was not co-starring with his

wife. Eventually Burton would also torpedo his career with an astounding post-Boom! parade of gobsmackingly spectacular garbage—Candy, Bluebeard, Hammersmith is Out, The Klansman, The Assassination of Trotsky, The Exorcist II: The Heretic; The Medusa Touch, etc.—but at the moment he was riding far higher than Taylor was.

As for Boom! itself, as I noted, the project was plagued by production overruns that saw the film’s final cost balloon to two and a half times the original budget. A central reason for this was Burton and Taylor’s refusal to confine their bad acting to the screen. The couple lived offshore during the production aboard their newly acquired, 130 foot luxury yacht, and seemed to take a rather laissez-faire approach to shooting schedules and suchlike. Things weren’t aided in this regarded by the pair’s ever increasing drinking issues, either. Life was a big party for the Burton’s, pretty much literally, and director Losey seems to have just tossed up his hands regarding his temperamental stars.