Welcome, folks, to the B-Masters’ Subculture Roundtable. For my entry, we’ll examine what is really a tale of two subcultures, one old and losing its once great power and influence, the other young and just coming into its own.

For more tales of punks, pagans and beatniks, click on the banner above and be whisked away to the Roundtable Supersoaker—because that’s just what The Man wants you to do! BWAHAHAHAHAHAHAHA!!

Note: For reasons I’ll go into later, I was forced to review a truncated version of the movie. This is currently the only version available, and with the film in the public domain, is likely to remain the case. Still, I have kept this piece unpublished for many years now in deference to this fact. Even though I have finally decided to post the review, I would encourage anyone who seeks to be fair to the crafters of the original, longer version of the film to keep this in mind. Although I wager that version sucked too; in fact, as it was longer, it may have sucked all the more.

Warning: For those (should they exist) who seek to see the movies reviewed here, be aware that this film unsurprisingly features the near constant use of offensive racial expletives.

We open on a road sign warning to “drive carefully,” and noting that our location is “Wallace Country.” For the historically disadvantaged, this presumably sets the film in Alabama, where George Wallace was Governor at the time. Wallace, later crippled in an assassination attempt while running for President, achieved a sizable notoriety for literally standing in a schoolhouse door to block the court-ordered integration of black students. (It should be noted that Wallace repented of his racialist sins before his death several years back.)

In other words, this is the ’70s version of a sign reading ‘David Duke Country.’ Apparently, the wily screenwriters bypassed setting the film in a town named ‘Bigotsville’ as perhaps being just a shade too on the nose. Still, the sign’s red, white and blue coloring serves to provide the savvy viewer with all they need to know. These are, after all, the national colors of Amerikkka.

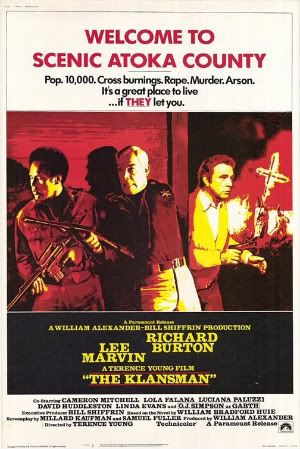

Incongruously, we hear an overloud engine while reading the “drive carefully” sign. I believe this represents the director’s ironic yet artistic foreshadowing of trouble ahead. This premise is quickly confirmed when the opening credits reveal our stars to be Lee “Delta Force” Marvin and Richard “Exorcist II” Burton, along with help from Cameron “Frankenstein Island” Mitchell and O.J. ‘I may have cut my wife’s head off, but hey, I’m not a racist‘ Simpson.

Burton, naturally, needs no introduction to the citizenry of Jabootudom. He was the worthy recipient of the Medved Brothers’ award for the Worst Actor in cinema history in their seminal tome, The Golden Turkey Awards. Anyone wondering why need only watch our current subject of inquiry. Or Exorcist II: The Heretic. Or Bluebeard. Or Hammersmith is Out. Or The Medusa Touch. Or The Assassination of Trotsky. Or The Sandpiper. I could go on, but that way lies a severe case of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.

The disruptive engine noise proves to emanate from a police motorcycle, ridden by the aforementioned Bad Movie icon Cameron Mitchell. This is a sly augury that Authority will be the source of Chaos here, rather than Order. (Wow!) Nor is our growing unease abated when the theme music kicks in. This proves to be chicken-fried, very ’70s blaxploitation-type stuff. Added to the other indicators seen during these brief moments, and it seems clear that a rather particularly 70’s crapfest is heading our way.

Our director is Terence Young, an Englishman responsible for three of Sean Connery’s classic James Bond films. These include From Russia With Love, arguably the series’ finest chapter. Even so, one might argue that a Brit seems an odd choice to examine the seething racism that underlies, indeed (or so the film would have it), defines our nation. Still, he manages to bring all the gritty realism of his Bond movies to bear here.

Jabootuites will continue to oooh and ahhh with pleasure as the credits continue. Amongst the cast is songstress Lola Falana. A singer in a dramatic role is generally a good sign (at least by our standards); this being known as the Tony Bennett Rule. Also notable is the inexplicable presence of one Luciana Paluzzi, who I believe was the demon in Exorcist II: The Heretic.* You’d think working with Burton once would be enough.

[*Actually, the Italian sexpot is best known around these parts as the female lead of The Green Slime.]

More pertinently, Cameron Mitchell’s moniker appears nice and high in the credits. Often regulated to bit parts in his studio films, it’s obvious that here he’ll be popping up with some regularity. Meanwhile, the film’s use of truly silly ‘down home’ monikers is established by Mitchell’s character name, which is (I swear!) Deputy ‘Butt Cut’ Cates. Presumably, this appellation will prove to derive from his habit of smoking cigars. I guess. C’mon, man, I don’t know.

Mitchell once starred in real movies like Gentlemen Prefer Blondes with Marilyn Monroe. Although The Klansman was a major, star-studded studio project, Mitchell’s role here is an early indication of the deep career slide that would eventually find him appearing in stuff like Kill Squad, Nightmare in Wax, Supersonic Man and the truly insane Frankenstein Island. Having both Burton and Mitchell in the same picture indicates that Jabootu had a personal horn in the making of this one.

Let’s continue. Hmm, Linda “Mitchell” Evans. Good, good. But then… “and O. J. Simpson as Garth”. The appearance of his credit is heralded when some fairly indecipherable ‘soul’ singing commences. This tune, we’re informed, was being performed by The Staple Sisters. No false advertising there, as it explains why hearing their crooning made my forehead feel like it had been assaulted with a stapler.

We cut to another street and see Lee Marvin, here in the personage of one Sheriff Bascomb, driving around. He cruises through a Black neighborhood, then out onto a highway. Eventually he turns onto a side road leading to a secluded wooded spot. He gets out and pulls aside a large branch which is blocking the road. This, if I’m not mistaken, indicates that Octaman is in the area. (I wish!)

Over the noise of a crowd of extras Watermelon & Cantaloping, we hear a woman screaming. Sure enough, a bunch (Herd? Swarm? Murder? Plug?) of rednecks is tossing around an attractive young black woman presently attired in your standard torn clothing. Well, at least they waited two entire minutes before getting to some stereotypical hillbilly types. Meanwhile, a heavy-set Black guy is also taking some abuse.

The goons are brought to attention by a honked car horn. It’s Bascomb, who apparently knew just when to appear at this secluded spot. (“Well, it’s Tuesday. Guess I’ll mosey over to the 2:15 racial hazing.”) When this fails to do the job, he walks down and tells the ruffians that they’re trespassing and had best take off. I can only imagine this scene going in another direction had it appeared in an episode of Walker, Texas Ranger.

Here, instead of a series of spin kicks, the sullen crowd merely begins to disperse. A good ol’ boy informs Bascomb that it was just a bit of harmless fun, and that “old Lightnin’ Rod don’t object.” Presumably, Lightnin’ Rod is the portly Black gentleman. Said line, by the by, was obviously (not to mention poorly) looped in during post-production. The words so mismatch the guy’s lip movements that we half expect Godzilla to come looming up over a nearby hill. (I wish!)

To prove their earnest good faith, the fellow notes that “we was goin’ to give ‘im a dolla’.” Well, no harm done, then. When someone asks Bascomb how he knew where they were, he replies that “Lightnin’ Rod’s Mama saw you fetch ‘im.” I’m not quite sure that that answers the question, but anyway. Still, it’s good of the sheriff to point the finger at the old black woman who ratted these hooligans out to the law.

Bascomb collects Rod’s dollar and walks over to give it to him. Yes, really. This scenario raised more questions than it answered, however. For instance, shouldn’t the abused Black woman get a dollar, too? It’s that old glass ceiling, I reckon. Bascomb asks Rod if he knows how to find his way home, from which we surmise that ol’ LR is a bit slow. Man, black and mentally handicapped—that’s just begging for trouble in this kind of movie.

Rod nods, and the Sheriff sends him off on foot to head home. Then Bascomb agrees to give Bobby Poteet, one of the white dudes, a ride over to his wife, who’s doing some bird watching. I believe that this is meant to indicate that poor black folk didn’t always get a fair shake in the Alabama of that time.

I think I know where this is going. Remember In the Heat of the Night, one of the few decent Hollywood ‘message’ films about race? (Seriously, just try watching Otto Preminger’s Hurry, Sundown, or Stanley Kramer’s Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner or, well, this.) Rod Steiger played a racist sheriff whose grudging respect for a black northern police detective forces him to painfully examine his beliefs. I’m assuming that Marvin’s character is destined to have a similar arc. Although ‘ark,’ as in Raiders of the Lost Ark, might be a more appropriate term. As I recall, watching that ‘ark’ also made you scream in horror as your head shriveled up.

Bascomb drops off Poteet and continues on, whereupon we are honored to witness an epic meeting. Bascomb parks his car and we see (yes!) Richard Burton standing nearby. Burton’s playing one Breck Stancill, and his presence here continues the bizarre tradition of casting British actors in movies about American racial Issues. For further examples, see James Mason in the repulsive Mandingo and Michael Caine (hello, old friend) in the cretinous Hurry, Sundown.

Stancill speaks, although we can barely understand him. And I’m being generous with that ‘barely.’ Mushmouth from the Fat Albert show talked more clearly. His character also exhibits a, shall we say, extremely noticeable limp, of the sort seldom seen outside of junior high school productions of Richard III. Savvy Jabootuists will instantly anticipate that we’re eventually going to get an elaborate, and undoubtedly silly, explanation for said infliction. It’s inevitable, like ‘Hymie Kelly’ explaining his ludicrous moniker in The Oscar*.

[*Future Ken: Actually, other than a passing reference to his being shot up in Korea, this doesn’t happen, at least in the shortened version I’m reviewing. Still, I’d be more than a little surprised if the story wasn’t told at greater length in the full cut of the film.]

Stancill invites Bascomb to step inside his home. Further dialogue ensues, whereupon we discern why we’re having such a hard time figuring out what Stancill is saying. It’s because Burton is trying to do a ‘Southern’ accent. (This similarly plagued, again, Michael Caine in Hurry, Sundown.) Since he’s also attempting to act ‘laid back’ in the Southern style, he speaks in a soft, molasses-thick mumble that would do Marlon Brando proud*. I’m not exaggerating. Half the time you can’t make out what he’s saying. It’s like he prepared for the role by studying Arte Johnson’s Dirty Old Man character on Laugh-In.

[*Now that I think about it, Brando’s similarly gawdawful ‘Southern’ accent in Reflections of a Golden Eye is one of the few such that could actually hold its own against Burton’s here.]

Bascomb’s come to ask Stancill if he intends to let the “Black Vote Demonstration” (in 1974?) camp on his mountain. The locals are curious—and, duh, rather hostile to the idea—so Bascomb’s come to check things out. Stancill replies that he wasn’t planning to, but is clearly annoyed that people are sticking their nose into his business. His conclusion, that he’ll “try to maintain a dignified neutrality,” looks not to be the answer that Bascomb was hoping for.

Richard Burton and Lee Marvin bring all their vast thespian skills to the fore.

Meanwhile, Poteet, the fellow Bascomb had earlier given a ride to, is pulling his dying old beater to the side of a deserted road. He and his inexplicably hot wife Nancy (Linda ‘Younger than Ursula, Older than Bo’ Evans) take the opportunity to snipe at one another, clueing us in that theirs is a less than perfect union.

Her mood isn’t improved when Poteet suggests that they hike into town and arrange for a tow truck. Replying that she’s tired, Nancy decides to stay with the car. Her fatigue is understandable. If I were working as hard at a bad Southern accent as she is, I’d be downright exhausted. Besides, if she didn’t opt to stay alone on a deserted road she couldn’t suffer a horrible fate that will drive the plot along.

Sure enough, literally less than ten seconds after her husband takes off, we see a black fellow’s hands—the better to disguise his identity until it can be used as a ‘plot twist’ later in the movie—moving around the car. Our mystery assailant attacks Nancy and we fade to bl…uh, we fade into the next scene.

We cut to a meeting at what I guess is supposed to be the local Klan lodge. The room is festooned with crosses, so that we know where to assign the blame. That’s right: Christians. You just can’t turn your back on ’em. The town’s Mayor (character actor David Huddleston) is reassuring his fellow rednecks that the Black Vote Demonstrators won’t be allowed to act all uppity and such.

”RNC Strategy Meeting,” a sketch from Fox’s hilarious and provocative new comedy show The Seth McFarland Hour.

The mayor, a wily rascal, tells his fellow, er, Klansters that they aren’t going to officially do anything against the agitators. His plan, confirmed with the local Grand Wizard, is just to allow the demonstration to happen, ignore it, and let the whole thing blow over. His more lunkheaded comrades, however, express a wish for more direct action.

Some more stuff happens, which I couldn’t quite follow due to the rather confusing fashion in which it’s presented. The gist, however, is that the GOBs (Good Ol’ Boys) are planning to go out that night and express their wishes to the local African-American community, regarding how they would be better off not supporting the demonstration. We see that Cameron Mitchell is amongst their number, although the fact that he’s playing a heavy is hardly much of a surprise at this point of his career.

The Mayor, miffed at the GOBs not following his orders, expositories on how he’s the lodge’s “damn exalted Cyclops.” However, he’s mostly concerned about maintaining plausible deniability. (That sly devil!) Therefore he warns the others not to specifically inform him of their plans, in case he’s ever called into court. He also cautions them not to kill anybody or dynamite any black churches.

This is followed by a truly offensive speech again equating Christians with the Klan (see IMMORTAL DIALOG). Apparently, some stereotypes are OK, especially when crusading British film stars and directors are kind enough to come across the pond and make us troglodytes a movie that rips the lid off the problems with our country. And if they pocket some huge paychecks in the process, hey, what could be more just?

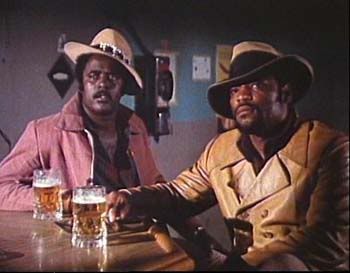

We cut to Bascomb entering a black hang-out. Since the film was made in 1974, all the patrons are dressed like Huggy Bear and the obligatory funky music is blaring away. The Sheriff starts interrogating a chap named Willy about his whereabouts at the time of the attack on Nancy. He then produces an warrant for Willy’s arrest. When he informs the suspect that the arrest will be on the charge of rape, a surprised Willy looks over to some pool-playing compatriots. One of them proves to be Garth (O. J. Simpson).

Garth tosses Willy a pool cue, almost taking the guy’s head off. (Hmm, since we’re talking about O.J., maybe I should rephrase that.) Willy uses the implement to take a swipe at Bascomb. Oh, yeah, that’s a good idea! Bascomb disarms the miscreant and checks to make sure the hostile patrons don’t intend any further interference. Then he escorts Willy outside.

”Paramount Picture’s searing social drama The Klansman takes a bold stand against those who would belittle and stereotype today’s proud black Americans…”

O.J. Simpson, to the right, prepares to give another actor his cue. (I know! I can’t believe how funny I am, either!)

A pickup truck pulls into the lot and Bascomb orders Willy to get into his police car. Willy is no sooner secured then a contingent of armed GOBs jumps out of the truck. They inform the Sheriff that they plan to “save the county the cost of a trial.” (Apparently, they also intend to save the movie the cost of original dialog.) Bascomb, however, being Lee Marvin and all, machos his way out of the situation. Garth and a buddy watch as the dejected goon squad drives off.

We cut to the same posse of doofi driving down (yet another) deserted road. Somehow, they end up passing the walking Garth and his pal. This is odd. Both groups left the bar at about the same time, the black guys on foot and the white guys in the truck. Anyway. Seeing a few members of a discreet insular minority at their mercy, the rednecks decide to have some fun. So saying, they drive at the pair, forcing them to leap off the road.

Despite the fact that the truck is cruising around at a pretty good clip, Garth manages to hit one of them an apple. (Yes, an apple). This, naturally, results in the GOBs disembarking with the intention of kicking some ass. Being white guys, however, they can’t outrun their intended victims, and instead throw pot shots after them. Garth escapes, but his buddy takes one in the leg. He’s soon executed, as an enraged Garth helplessly watches from a nearby bush.

Cut to the local barber shop, where one of the customers is the guy who pulled the trigger on Garth’s friend. Deputy Cates strolls in, waving “a little something from the national office [of the Klan].” The GOBs are already spreading rumors that the killing was the work of either a local black or one of the ‘agitators’ coming in for the demonstration. Meanwhile, Stancill, having apparently just gotten his hair cut, stops to examine a KKK poster on the barbershop wall (!).

”Hey, everybody! The Klan bake sale is this weekend!”

He begins to read aloud the text of the poster, drawing the attention of the rest of the customers. I assume this is because of his impenetrable ‘Southern’ accent, which we hear at greater length than usual here. His rendition includes another line about the horrifying possibility of “granting the Negro the ballot”. (In 1974?) Upon concluding his presumably dramatic (if indecipherable) recitation, he pulls down the poster, wads it up and tosses it to the floor.*

[*It was a lot cooler when Christopher Hitchens did the same thing, bless him.]

Cut to Cates at the town jail, expressing his bewilderment to Bascomb that Stancill “even hates the Klan!” When Bascomb notes “he has his reasons,” Mitchell replies “that happened a long time ago.” I’m sure we’ll be hearing that piece of backstory at some point. Cates starts threatening to kick Stancill’s ass. Trixie, Bascomb’s secretary (and Stancil’s lover), warns him that Stancill “knows Karate from the Marines.” (Plot point!)

Actress Luciana Paluzzi thinks back to the days when she starred in stuff like The Green Slime, and wonders, “Where did it all go wrong?”

Bascomb warns Cates that he won’t tolerate any violence against Stancill. Cates sullenly capitulates, but looks through the window. Noting that Stancill is across the street at the bus depot, he laughingly pretends to shoot him, making silly ‘gunshot’ noises like a ten year old. Bascomb hears this and runs over to see what Stancill’s doing at the depot.

He is, we learn, carrying the bag of Loretta (Lola Falana), an attractive young black woman. Like many of the other cast members here, Loretta’s accent sounds like a code developed to frustrate upper echelon enemy cryptographers. Other than the fact that she’s a returning local, I couldn’t make out much of what she was saying. She’s single, and, uh, that’s about all I got.

”So let me get this straight…they hired two of most famous movie actors in the world to play the white dudes, but for the black leads they cast a singer and a football player. Uhm-hmm.”

We cut to what I guess is supposed to be Loretta’s cabin. This resembles something that school children would build to represent the home of Little Red Riding Hood’s Grandmother. Loretta hears a knock, and finds a stylishly dressed (sorta) black man and a mangy white hippie type at her door. If you guessed that these two are with the Demonstration, give yourself a cookie.

The mangy hippie dude turns out to be the Rev. (!) Josh Franklin. His associate is one Charles Peck. We learn that Loretta was part of “the Movement” back in Chicago, and they’re here hoping to garner her help. Loretta demurs, warning of bloodshed. Brother Peck, however, isn’t fooled. “I got you pegged, Baby” he suavely notes. “You ain’t no Auntie Tom handkerchief-head. You’re in the Movement, all right, right up to your polished fingertips.” Ah, the noble tradition of American blacks judging each other’s blackness. Brings a tear to the eye, it does.

Rev. Josh interposes himself, asking if Stancill is a “Brother of the Sheet.” (Wow! Another patently made-up piece of pseudo-slang to add to our collection! I’m putting that one right before “busting thumb.”) Loretta points to a tree about ten feet away. She explains how Stancill’s great-grandfather, an abolitionist, was strung up from it by “rednecks.” Rev. Josh, however, wants to know what Stancill’s done about it. You’re either part of the solution or part of the problem, dig? Loretta replies that he mostly just keeps to himself, drinking. (Boy, that must have been a real stretch for Burton.)

”And so you see, ma’am, for less than the daily cost of a newspaper, you can help people like my friend here get new and much less embarrassing sports jackets.”

Let me be sure that I communicate just how obnoxious ‘Rev.’ Josh and Peck are. Their utterly holier-than-thou and judgmental—albeit in a secular way, of course—attitudes wear quite thin, quite fast. Meanwhile, Peck’s calling Loretta ‘baby’ all the time, along with his crude come-ons, grate heavily on the nerves. Sure, they’re on the right side. But they’re still dicks. The only question is whether the film is aware of that or not.

Later, we see a hooded head peer through a window of a shanty, accompanied by a burst of funk music. Inside the shack we see one of the rednecks who killed Garth’s friend. The hooded figure knocks on the window. The occupant, seeing the uniform and figuring that a little fun’s going on, quickly gets dressed. He comes out with his Klan outfit half pulled on, whereupon he notices black hands protruding from the sleeves of the other guy’s outfit. No, it’s not Cleavon Little from Blazing Saddles. (I wish!) It’s Garth, and the redneck is soon in Hog Jowl Hades.

Bascomb is next seen talking to the press. They ask him if he believes the killer to be black, a question he refuses to answer. Said reporters, including a dude (in the actual, Western sense of the term) from The New York Times (!!), are here to cover the Demonstration, and they demand more info. Bascomb, however, maintains his silence.

In a charming scene, Bobby Poteet comes in and tells Bascomb that he’s leaving town, and without his wife. It seems that living with a woman who’s “been with” a black guy is more than he can stand. And boy, are the neighbors talking. “Why did this thing have to happen to me?” he asks. Get it? Because it really happened to Nancy. I think the point of the scene (other than to utterly repulse us, and mission accomplished) is to indicate that Bascomb is starting to get his fill of the town’s ignorant racism.

We cut to a scene at the town church, or at least the one for whites. This provides yet another opportunity for the film to hamfistedly equate Christianity with the vilest racism. Considering the lengths at which this idea is run into the ground, you can only wonder what the eleven minutes yet missing from the various public domain DVD versions entailed. (Oh, and should you be thinking that ‘Rev.’ Josh is meant as an attempt by the filmmakers to show that there are good Christians, you might be right. Such, apparently, would be the sort who don’t talk about God and salvation and all that other dreary stuff. Souls, smouls, we want temporal Justice, baby!)

The preacher’s pernicious fire and brimstone sermon is interrupted by the arrival of Nancy. As indicated, her rape by a black has made her an outcast. Her appearance thus provides the assemblage with a prime opportunity to engage in a classic exhibition of some good, old fashioned ‘watermelon, watermelon’ noises. Ah, sometimes the quaintest traditions remain the most pleasing.

When Nancy refuses to budge her fellow parishioners begin bolting from the church. The Preacher asks her to leave, allowing her a speech (Oscarâ„¢ Clip!) about how they’re the ones who are defiling the church with their hatred. Ah, now I get the scene’s subtle point. Then Bascomb shows up (?) and escorts Nancy out. Anyway, I hope we all ‘get’ now how Christians are evil racist hypocrites and whatnot, because I could really do without yet another scene explaining this to us.

We join Bascomb, who’s having a drink at Stancill’s place. He makes what seems like a very odd suggestion, that Nancy be allowed to come up to Stancill’s mountain. There she’d be free from the catcalls of the town. (In the middle of this, the filmmakers foley in a rooster call in a comically woeful attempt to lend verisimilitude to characters supposed rural surroundings.)

Stancill has a counter-proposal (and a much more logical one), offering to slip Nancy a couple of hundred bucks so that she can leave town. This suggestion ends up being ignored, however, for no good reason other than the necessities of the script. Bascomb notes that the locals feel that, given as how Nancy survived the rape, she should have had the decency to off herself. It’s her standing up for herself that’s causing all the problems.

Stancill rather obviously notes that he’d have to take her in and feed her and generally assume responsibility for her. He tells Bascomb to tell her no. Bascomb replies that Stancill can tell her no—she’s waiting outside in his squad car. This seems a little pushy. Imagine a friend coming to your house, and out of nowhere demanding that you take in a certain homeless person. When you demur, he orders you to go give that person the news. I mean, why is it Stancill’s responsibility to say anything to her?

Yet Stancill dutifully limps outside to the car. He silently offers Nancy the money, but she turns away her head. Routed by this brilliant strategy, Stancill naturally capitulates and asks her in. He is, after all, a Good Guy. Still, given that this is a movie, and that Nancy is exaggeratedly attractive in a ‘movie actress’ sort of way, well, does anyone else see a romance on the horizon? (Actually, I don’t know if I can see it, but I can sure smell it a’comin’. And it’s mighty ripe.)

His mission accomplished, Bascomb drives over to the Mayor’s house. There Hardy chews him out for finding Nancy a place to stay. (News travels fast, I guess.) In the course of his tirade, big surprise, he threatens to take away Bascomb’s badge. Since we’re down South, the writers throw in some down-home dialog. “You’re the best Sheriff this county ever had,” the Mayor admits, “but you don’t know any more about business than a hog knows about Sunday.” Wow, Baltimore native—and Mr. Magoo co-creator—Millard Kaufman sure ’nuff knew his Southern idioms.

Being an Evil Mayorâ„¢, Hardy gives a speech about how Bascomb’s rocking of the boat threatens the town’s business interests. Blacks are heading north looking for jobs, or joining the Army, or whatnot, depriving the town of cheap labor. I’m not sure what this has to do with Bascomb, or how they figure on stopping this migration. (Better jobs? More pay?) Meanwhile, a black servant in white livery appears and brings Bascomb a drink—a Mint Julep, no doubt—thus providing the audience with a conveniently abject example of the local black community’s economic and political status.

Hardy also expositories about how a majority of the town’s citizenry is black (!). He notes that they could decide to elect a black sheriff, putting Bascomb out of a job. This notion appears to strike home, although Bascomb’s apparent policy of (comparative) racial evenhandedness would seem to his best chance of forestalling that eventuality. Certainly throwing in with the local Klan members seems a less promising long-term approach. In fact, isn’t it Hardy who should be worried?

In a ludicrous attempt (at this late juncture, anyway) to lend the Mayor’s character some ‘depth,’ they have Hardy exclaim, “Don’t look at me like I’m the heavy.” He wishes things were different, but the real villain is, you know, “The System…and we’re all of us caught up in it!” (Oh, bru-other! OK, now I know that this was made in 1974.) Hardy is most fearful of the Northern Press getting wind of Nancy Poteet’s story, her rape and subsequent ostracization, which would really see the fecal matter impacting the air-circulating mechanism.

Back at the Sheriff’s office, the aforementioned members of the Fourth Estate are annoying Bascomb’s secretary, Trixie. They’re miffed because Stancill has had the effrontery to ignore their interview requests. This situation naturally provides Trixie a chance to toss out even more expository data, for instance how the Stancill family’s been living here back eight generations. The most pertinent factoid is that the Black ‘relievers’ (welfare recipients) living out on Stancill Mountain have it better than the local White relievers. Stancill, you see, doesn’t charge them rent, and moreover provides them with basic supplies. This is the source of much of the local white folk resentment against him.

Guess which one of these guys is supposed to be the reporter for The New York Times. Hint: It’s not the one on the right.

Moreover, Stancill is so environmentally inclined that he leaves rotting trees standing on his property to encourage a certain type of bird to stay in the area. In fact, aside from being played by an extraordinarily bad actor—Burton tended to be either brilliant or flat out awful, one or the other—he’s a regular Gandhi. The scene ends with Trixie agreeing to attend the Johnson funeral (the guy Garth whacked) with the reporters. (?)

Cut to the funeral. It’s a grand affair, with marching bands, proud displays of both the American and Confederate Flags, and, yes, a burning cross, which the film rather hamfistedly focuses on so as to be sure we don’t miss it. Good thing, too, because it’s pretty easy to otherwise overlook a guy in Klan robes toting around a towering, flaming wooden cross.

Then we see Garth hiding in a nearby tree. His appearance is naturally accompanied by a blare of Generic Funk Music. You know, because he’s black, and black folk like the Funk Music. It just goes to figure. Raising a rifle, Garth mows down the fellow hoisting the burning cross, who conveniently happens to be the very miscreant who shot his friend earlier.

Pandemonium ensues. People scream and dive to the ground. A driverless limousine rolls back down a hill. (I actually thought this a bit strange, given my previous assumption that the ‘parking brake’ had been invented prior to 1974.) Meanwhile, another car attempts to avoid the limo and smacks into yet other vehicles. This causes the incendiary devices that are rather obviously set under the rear of each automobile to explode, suggesting that perhaps Dateline was shooting footage for another special report.

The fact that said cars were traveling maybe a combined twenty miles an hour makes the explosions even more dubious, not to mention unspectacular. Unsurprisingly, one of the immolated cars then rolls back into a tree. This triggers another, utterly gigantic explosion, apparently the result of the car being fueled with Atomic Gasoline.

Hmm, Garth’s revenge scheme seems to be going well. Yet, I can’t help feeling that opening fire at a funeral, even of a Klan member, is somewhat counterproductive to the Black Cause. Especially given all the Northern Press in attendance, who might otherwise be expected to be somewhat sympathetic. Of course, given the time period, said reporters might consider this a particularly winning act of Radical Chic, a droll conversational bon mot to drop at Leonard Bernstein’s next soiree.

Given the circumstances, the ceremony moves indoors to someone’s house. There we see mourners singing a (*gasp*) Christian Hymn. Deputy Cates, meanwhile, is passing around his theory that the Northern ‘agitators’ are responsible. Another Good Old Boy, however, proves a wee bit swifter than the rather dense Cates. He explains that the assailant is undoubtedly Garth, who presumably plans to pick off everyone involved in killing his friend, one by one.

Cates decides to sidestep Bascomb and go after Garth himself. He assumes that the fugitive is hiding at Loretta’s, who, after all, has been seen smoozing with those darned hippie agitators. (OK, one doesn’t mean the other, but again, Cates is a tad slow.) His associate warns that this plan of action will necessitate going up against Stancill. Cates blusters that he welcomes it. However, tonight Stancill will be having dinner over at the Bascomb house, as he does every week. Therefore they should have no problem avoiding him.

The GOBs jumps into a truck and drive out to Loretta’s. When she has the temerity to ask Cates if he has a warrant, he makes to stove her door in. Realizing that she has little choice, she gives up trying to keep them out. While his associates search the house, Cates vaguely threatens Loretta regarding her tossing in with the Demonstration. When a disappointed Cates learns that Garth isn’t to be found, he decides to take Loretta in for questioning. Why? To advance the ‘plot’ in some fashion, I guess.

We cut to the Bascomb residence. The Sheriff, his wife, their teenage son Al, and Stancill are just finishing up dinner. At least I assume his son is supposed to be a teenager, since a major plot point is that Bascomb is desperately trying to wrangle him a spot in West Point. This is the main reason Bascomb plays along with Mayor Hardy as much as he does, since his backing is essential to Al being accepted.

Despite this being pretty much Al’s entire plot relevance, the guy they cast to play him was fully thirty years old at the time the film was made. Moreover, he entirely looks it. Needless to say, this makes him a bit long in the tooth to be a prospective West Point cadet.

Furthering this plot point, Bascomb gets a phone call. It’s the Mayor, complaining that Al has been wandering around town and tearing down Klan posters. Bascomb confronts Al and asks him to cool it. However (remember, this is 1974), Al retorts that he doesn’t even want to go to the Fascist Academy, er, West Point. Instead, he wants to be a tree farmer (!). Hey, man, far out! Groovy! Right on!! Etc!!!

Bascomb sends Al off and pours drinks for himself and Stancill. (I’m sure teetotalers Marvin and Burton required expert instruction on this ‘drinking’ stuff.) Here the two reassure the audience that they are good men by spouting some anti-Klan rhetoric. Gee, that’s a bold stance. Meanwhile, and as usual, we can barely make out what Burton is saying. He’s somewhat more coherent than Boomhauer from TV’s King of the Hill, but not much.

Worse, the screenwriters provide Marvin with expository dialogue that establishes facts about the Klan. Inevitably, this suggests the screenwriter having conducted a diligent ten minutes browsing through a volume from the World Book Encyclopedia. The intention is to make the Klan, like the supposed ‘Fourth Reich’ Nazis in The Holcroft Covenant, seem much more powerful a force than the actual organization was at that point in time.

Needless to say, they can’t admit the Klan was well on the way to becoming a paper tiger when this film was being made. If they did, think about how much harder it would be for all those involved here to slap themselves on the back. You know, about how brave they are to make a film exposing this menace to the rest of the country. Plus, think about all those unenlightened folks out there, who sans Hollywoodian instruction would fail to glean that the Klan is, you know, bad and stuff. People like, well…us, I guess.

Bascomb tries to get Stancill to cool things down, fearing his friend might become a victim of the virtually all-powerful Klan. Bascomb warns him that his name is on a list kept at the state Klan headquarters. Stancill asks him how he knows this; is Bascomb himself a Klan member? Bascomb angrily jumps up from his chair. Due to an amusingly awkward bit of blocking, actor Marvin has to check his momentum and swerve around a nearby hanging lamp. That’s funny. You’d think a guy would be aware of where the lamps are in his own house.*

[*Unless he was an actor shooting in somebody else’s house, that is.]

”You’ve got a lot of nerve coming in my own house and accusing me of WHOA, WHO THE HELL PUT THIS THING HERE?!”

Bascomb replies that he’s had to swear allegiance to many things to keep his job, “even God!” (*Gasp!*) Why, he elaborates, in this state alone senators and Supreme Court justices are Klan members. In any case, since Bascomb doesn’t outright deny the charge, we can only assume that he too is a brother of the sheet. Whoa. Man, I’m about ready to give up. There’s obviously no stopping these Klan guys. They’re going to rule the country!

I just want to take this opportunity to reassure our readers, however, that absolutely no one, not one of the over three people currently associated with this website, is a member of the Klan. I know, I know. It seems statistically impossible. Yet I swear it’s true. Although I should be totally up front and confess that both Techmaster Paul and I are, in fact (*gasp!*), Christians.

Despite these assurances, I can see how, in light of this damning information regarding Paul and myself, how some readers might not want to take any chances. Therefore, anyone who feels that they must immediately leave off reading this review and never return to our site, well, we’ll understand. (I can’t promise, however, that you won’t then be put on our State Headquarters List! BWAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHA!!!)

We cut to a lumberyard warehouse. This is pretty convenient, because I’m bored! (Uh, that actually might work better as a vocalized joke. Sorry.) A pickup truck enters. A bunch of the goons, including Cates, haul a screaming Loretta out of the vehicle. Cates calls for her to be tossed to him. Fortunately, they fade away at this point (at least in this shortened version) and her fate is thankfully left to our imaginations.

Later on, Bascomb, having gotten a call that something’s going on at the lumberyard, drives over. Next we see him in the car with the abused Loretta. In a scene that casts Bascomb in a less than flattering light, he refuses to take the seriously wounded woman to the hospital unless she agrees to make up a story blaming some black dudes for her condition. Loretta, close to bleeding to death, is forced to agree.

Cut to the hospital. Being a movie character, Loretta has kept her word to Bascomb, telling the doctor that four black guys attacked her. For absolutely no reason, the fact that Loretta was a virgin surfaces. This is, presumably, a pathetic and rather offensive attempt to make her more ‘sympathetic.’ Gee, if we’d known she was pure and unsullied, we might have found her rape to be somewhat ignominious.

Stancill goes into Loretta’s room. He tells her that she’ll be as good as new as soon as she gets back to Chicago, but it’s evident that her spirit’s been broken. This scene is horrifically maudlin, yet at the same time excruciatingly dull. Falana actually isn’t bad. Burton, however, pretty much sleepwalks through this film, a habit of his when he did a film purely for the money. (See Douglas’ review of Exorcist II for another prime example.) His artistic lethargy in this film has been consistently annoying, especially combined with his (at best) half-legible accent. Here, however, in a scene meant to engage us emotionally, it’s even more alienating.

Loretta, to whom Stancill is a father figure of sorts, wants some advice. She tells him the truth about her attackers and asks what she should do. Stancill tells her that that’s “killin’ talk,” by which I presume he means her life would be in danger were she to accuse Cates and her other white attackers. To protect her from further harm, he tells her to keep her word to Bascomb.

Next we cut to the Demonstration. Perhaps a hundred or so mostly black people are marching around a small, fenced-in area. They’re hefting signs with inspirational slogans like ‘Register to Vote’, ‘Black & White are Both Colors’, and ‘Same Public Toilets for Everyone’. Not exactly ‘Live Free or Die’, but hey, they’re trying. A couple of nuns are noticeably in the group, presumably to let us know that the ‘Evil Christian’ thing only applies to Baptists. Ah, that’s some good nuance there.

Next the Demonstrators break into a fit of (ugh!) ‘folk singing.’ As the lyrics to ‘As the Saints Go Marching In’ warble forth, we cut to a nearby hillside. On a public bench facing the Demonstration we see Garth eating a sandwich. (This naturally inspires us to wonder exactly where he’s been hiding). When he’s finished, he looks around and reaches down for a bag, from which he draws his rifle. I don’t blame him. I can’t stand folk singing either.

We then see various small bits. Townspeople are angry at Bascomb for allowing the Demonstration to continue. (Here’s an idea – ignore them. Then the TV camera won’t get any good pictures and the whole thing’ll blow over. P.S., this would also work now when dickwads like American Nazis hold their pathetic little ‘rallies.’) Next the Mayor asks Bascomb to put Cates back in uniform—apparently he was fired in one of scenes since edited out—but his request is ignored.

Then we see Stancill, who is called after by Rev. Josh. The good Rev. apologizes for what happened to Loretta, claiming that they never realized what a dangerous position they were putting her in. This assertion, I must add, doesn’t exactly speak well for their intelligence.

Stancill in reply asks why they’re just standing around. “Never underestimate just standing around,” Rev. Josh answers. Boy, he’s got a lot of gall saying that to Stancill. After all, Stancill’s being portrayed by Richard Burton, who apparently has based his entire characterization on the notion of ‘just standing around.’

This scene goes on for a while, painting an unabashedly noble picture of the heroic Rev., and grating on our nerves no end. Stancill asks if there isn’t some dude from their group who could help Nancy overcome her, uh, fears that no white man will ‘want’ her again. Rev. Josh asks why he, Stancill, doesn’t ‘help’ her out, but Stancill feels too sorry for her to make a move. As you can tell, it’s a charming little scene.

Next Rev. Josh (who just apologized for putting Loretta in danger!) asks Stancill if he can get Loretta to tell the truth about her assailants. When Stancill asks if he wants to get her killed, the noble Rev. begins jabbering about the Revolution. You know, the whole ‘can’t make an omelet’ thing. (Actually, right after I wrote the omelet analogy, Stancill used it onscreen. You have to get up pretty early in the morning to out-cliché these guys.) Understandably, Stancill nixes the idea.

One of the unhappy townsmen decides to hassle the demonstrators, but is felled as a shot rings. (Look closely and you can see the block of wood they placed under his shirt, to which they taped the squib.) Oh, yeah. Garth and his rifle. I almost forgot. Near catatonia will do that to you.

Pandemonium again ensues, and Garth makes his escape. Cops with shotguns and revolvers blast away, and the editing is apparently intended to make us believe that they’re shooting at him. Except that Garth was pretty much facing the demonstration head on, while the cops are firing straight off to the left. Also, Garth was clearly a good couple of blocks away. A possible shot with a rifle, but well beyond pistol and shotgun range.

Garth makes his escape by jumping in front of an oncoming train that cuts him off from pursuit. (Simpson apparently did this fairly dangerous stunt himself. Good thing for him he didn’t slip. Not necessarily a good thing for some other people, but good for him.)

Next, Stancill is in his truck driving Loretta home from the hospital. Loretta has decided not to return to Chicago. She’s going to stay here and fight the good, if tedious, fight. She tries to get Stancill to get more involved himself. She points out that one of the reasons that Cates and his bunch raped her was because they thought she was Stancill’s chickadee, and it was a way to pay him back for his Klan poster tearing-upping.

Suddenly, for no reason we can see, Garth comes out from under a blanket in the rear of the truck, waving a pistol and ordering Stancill to “keep driving.” Considering that they’re in the middle of the woods, and that Stancill’s made no sign of stopping, I’m not sure why he thought this order was necessary.

And yes, that’s right, this scene shows O. J. Simpson holding a man at gunpoint and forcing him to drive away in a white truck (rather like an old, oh, I don’t know, Ford Bronco) so that Simpson can escape the police. Make of it what it will, but the whole thing is damn weird. Was the real life O.J. reliving a scene from one of his old movies while leading the cops on his infamous highway chase? You can’t prove it, but damn, the scene is sure weird in retrospect.

”Look, Lola, all I’m saying is that this scene is ridiculous. Nobody in a million years is going to believe that something like this would really happen!”

Here we learn that Garth is an actual Revolutionary. Loretta asks why he broke up a “peaceful meeting.” Garth replies that such meetings are for “bourgeois Negroes.” (Early in the movie, the Klan was given much hysterical dialog about how the demonstrators were all Communists. This was meant to make them look stupid, since in Hollywood, anyone who is even vaguely anti-Communist is considered a moron and/or a fascist. However, now they’re giving Garth Marxist cant to spew. Make of it what you will, but you’d think somebody on the production side would have noticed all this.)

Loretta and Garth argue the relative merits of violence as a political tool, but on a level recalling third graders who forgot to study for a debate assignment. Eventually, Garth makes Stancill pull over. He waves his pistol at Loretta, telling her that “the only thing the Man understands is this.” (Ow! Somebody turn down the sound on the Cliché-o-meterâ„¢!)

When Stancill sides with Loretta, Garth chucks a loaf of bread at him (!) and calls him a “pegged-legged Honkey with a gun at your head, you dig?!” Garth then grabs some gear, and before running off into the woods, challenges Stancill to join the Revolution. If he does, Garth finishes, “you’ll know where to find me!” Uhm, in the back of his truck?

We cut to Stancill dropping off Loretta. She nonchalantly waves him good-bye, as if being hijacked by gun-toting Black Panther manqués were pretty much a daily event around here. Then he continues up the road to his house. He soon stops, however, because there are people in the road. One is Nancy, and we see that she’s leaning over a dead dog.

I think we can safely deduce that this is Stancill’s dog, and that this is a bit of retaliation from the Klan. I’m assuming that there was a scene with the dog in the removed,* as you’d think you’d want to set up how much he loved his pooch to increase the ‘tragedy’ of the scene.

[*There was an earlier reference to the dog being a purebred, but still, you’d think they’d have set up the situation more than that.]

Sure enough, Nancy approaches the truck and delivers the news. Stancill here shows at least somewhat more expression than he did when Loretta got gang-raped, but, you know, different drummers and all that. Burton portrays his grief and anger with a truly impenetrable display of mumbling, during which we can make out perhaps every sixth or seventh word. This is the kind of thing that would cause Popeye the Sailor Man to reply “Speaks up, ya swab, I cansk understands ya.”

However, Stancill ends up putting his arm around Nancy. Apparently, now that they’re fellow victims of Hatred (uh, sorta), they are now bonding. Say, could that be Love on the horizon? Sure enough, they walk towards his house. Stancill pours Nancy a drink and then begins pawing her. Remember, this is supposed to be therapeutic, as Nancy now suffers from a deep-rooted fear that no white man will want her physically because she’s been, you know, tainted. Well, don’t worry, ma’am, Breck Stancill’s here to manfully limp up to the plate.

This wasn’t a particularly good period for actress Linda Evans. Not only is she here subjected to the attentions of the bloated Richard Burton, but she would soon be engaging in make-out scenes with the Bigfoot-esque Joe Don Baker in the MST3K classic Mitchell. I must admit that I’ve hesitated to check out her filmography, for fear of learning that she played romantic leads opposite Rod Steiger, Slim Pickens and George Kennedy in other movies. Perhaps this explains her later attraction to skeletal New Age goofball Yanni.

We cut from the couple’s first passionate (ewwww!) kiss to a close up of a horseshoe spike as a shoe lands squarely. Gee, could that be some sort of droll sexual entendre? A camera pan reveals a redneck, who notes that “It’s been a frustratin’ [sic] week!” He’s having a bunch of guys over to play some shoes and moan about how things aren’t going their way. He does, however, take time to yell at his wife, Martha, and tell her to bring out beer. (Remember this minor character, she’ll have an ‘explosive’ part to play later in the movie.)

One of the guests is Cates, who begins riling up the others. His plan is to get Willie (the guy arrested for Nancy’s rape) and honor him with a necktie party. Martha, apparently freaked by the talk of violence, meekly takes her leave.

Sure enough, the next shot is of the guys holding a gun on Bascomb in his office. They’re trying to get him to turn over the cell keys. Just in case we missed one of the film’s central themes, the one of the lynchers earnestly says, “We’re all White patriotic Christians!”

Bascomb begins to fight back, but before any real violence can begin, Martha the One Guy’s Wife makes an appearance. One Guy reacts with anger at her Appearance, but she has some pertinent info for Bascomb. You see, Willie couldn’t have raped Nancy because…he was (*gasp*) with Martha that evening. (Oh, yeah, that’s sure helping his case with the locals! I don’t think the “he didn’t rape this one White Guy’s wife, he was having an affair with another White Guy’s wife” will really cut in his favor.)

One Guy flies at his errant wife. For some reason his buddies, who ostracized Nancy Poteet for being raped, pull him off Martha, despite the fact that she’s confessed to having voluntarily done it with a local black dude. This doesn’t really seem entirely consistent. Still, who can figure out those nutty White Patriotic Christians, huh? In any case, Bascomb herds the demoralized group out of his office. (I still think they’d want Willie worse than ever now.) He then promises Martha that he’ll have Trixie get her safely out of town.

Cut to Bascomb entering (Lightnin’) Rod’s shack to question him about the rape. Humorously, actor Marvin here flubs his line, clearly entering with “Hello, Ron“, although they apparently didn’t catch that he got the name wrong. After all, they could have had Marvin loop it correctly in post production, or even sampled the name from when Marvin used it earlier in the movie. In any case, the slip doesn’t exactly take away from the rumors that both Marvin and Burton spent the entire filming of the movie drunk off their asses.

At this juncture Garth (un)dramatically enters from the other room, explaining that Rod was with him that night, right here in the shack. Bascomb takes the opportunity to ask Garth about the murders, noting that “If I can figure it out, so can the Klan.” This apparently means that his good buddy Stancill didn’t tell him about the whole hijacking incident. Perhaps he’s been too busy engaging in purifying bouts of Sexual Healing with Nancy.

Bascomb tells Garth to leave town. Garth reacts by poking Bascomb with his rifle, and we’re supposed to be all freaked at the prospect that he may off the star of the picture half an hour before the movie ends (yeah, sure). They milk this for all the ‘tension’ it’s worth. That isn’t much, though, so they continue to dry milk it after that for a spell. In the end, though, Garth miraculously lowers his weapon and leaves. Whew! Well, I was sure worried!

In a scene that ranks fairly high on the We Never Needed to See That! scale, we cut to Nancy, wearing only a man’s shirt and carrying a tray of breakfast to Stancill as he (ewww!) lounges in bed. At least they had the taste to cloak Burton’s torso with some pajamas. In a big (if boring) moment, Stancill offhandedly asks Nancy if she intends to keep these early hours after they’re (wait for it!) married.

Unexpectedly, she turns him down. Having lived in this wee, stifling town all her life (surrounded as she is by Good Christian People, Good Country People, and White Patriotic Christians—three phrases that get recurring ‘ironic’ workouts here), she now wants to see the world. She promises to return, though, and to marry him if he still wants to.

He asks how she’s going to leave. “A long time ago,” she notes, “you offered me some money. Does that still hold?” A long time ago? In the movie’s terms, wasn’t it like (at most) a week ago? Perhaps she means that this occurred forty minutes earlier in the film’s running time. That, in fact, does seem like a very, very long time ago.

Cut to Nancy and Stancill in town, arriving at the bus depot. They engage in some nauseating ‘romantic’ patter, which would be worse, undoubtedly, were we able to much understand much of anything they were saying. (Apparently in awe of the Great Thespian, Evans seems to have adopted Burton’s mumbling technique here.) The film’s ubiquitously awful background music isn’t helping either. And you know, I really shouldn’t slight the ham-fisted musical score, given that it’s been reliably awful throughout the proceedings.

For some reason (IITS: It’s In the Script!), Cates just happens to be hanging around the bus depot, hanging up yet more Klan stuff. Slow day in town, I guess. This happens to set up one of the film’s ‘big’ set pieces. Cates tries to, well, bait Stancill by asking him if Nancy’s suitcase “is heavy for you?” This brings an ominous little bwa-wa-wa-wa note in the background music, like in a Spaghetti Western when Clint Eastwood asks some desperados to apologize to his mule.

Cates comes over and starts repulsively flirting with Nancy, trying to get Stancill’s goat. (Actually, he’s pretty successful in getting his pig, anyway, considering all the ham that Burton serves up here.) Reading some Klan garbage, he instead succeeds in getting Nancy to attack him. When he strikes her, Stancill springs—well, ‘springs’ might be overstating things a bit—into action.

Here we finally see Stancill’s bruited ‘karate’ skills in action. Remember in The Karate Kid, where Ralph Macchio was taught how to move by painting fences and stuff? Well, Stancill’s Sensei apparently taught him how to move by making him practice the dance popularly known as ‘The Robot’. Burton apparently thought that the essence of Karate was to move only one part of your body at a time. Which is, admittedly, more than he generally moves during the rest of the picture, especially in terms of facial muscles.

Humorously, this scene is a clearly very raw attempt to inject a little ‘Billy Jack‘ action into the film. It’s a pretty naked rip-off: Stancill, like Tom Laughlin’s Billy Jack, is a pacifist war veteran who unleashes his awesome fighting skills when confronted by Evil Racists. Except that Laughlin really knew hapkido, so his fight scenes were vastly more exciting (if even more hypocritical).

Stancill, of course, goes on to murderize Cates with his stiff fighting moves. Rednecks futilely exhort Cates to kick Stancill’s ass, as he reacts to Our Hero’s mighty blows by flying about and crashing through balsa wood doors and candy glass windows. This all occurs with country fried wakka-wakka music providing atmosphere in the background.

At one point, Cates flies through a bathroom door clearly marked ‘Women,’ presumably a comical dig at the unmanly thrashing he’s taking. Then he crashes into some luggage. (Too bad he didn’t ask O. J. Simpson, an expert on jumping over suitcases, for some advice.) Stancill delivers a final blow to Cates’ neck. Victorious, he then calmly escorts Nancy to the waiting bus and, romantically mumbling one last time, sees her off.

Much like the film itself, Cameron Mitchell ends up going awkwardly right into the toilet.

We cut to a bar, where we spot a somewhat worse for wear Cates. This sets off a wave of complaining about Stancill. One lad notes that “He taught Loretta how to type. And he got her a good job in Chicago, which is more than he’s done for any of you decent, God-fearing white gals in this whole county.” Aside from forging an intriguing link between “God-fearing” folks and racists—hmm, too bad they didn’t explore that issue in greater detail—the remark adds humor, as all the women in evidence here are obviously barflies and good-time girls.

The accusations mount, from Stancill hoarding Communist literature to the final straw, when it’s revealed that he doesn’t own a TV. (Why, how does he watch Hee Haw?!) Eventually, the patrons decide to string him up from the same tree his great-grandfather was hung from. This is followed by a veritable explosion of ‘watermelon, watermelon’ sounds.

We cut to Stancill’s truck arriving at the lumberyard. This apparently is where Mayor Hardy has his office, for we next see the two in discussion. The Mayor warns Stancill of a plan to burn his house down later that evening. Again, though, and maybe even more than usual, Burton’s mumble keeps us from understanding much of his side of the conversation.

Despite the warning and threats, though, it’s evident that he intends to stand his ground, no matter the cost. This causes the angry and frustrated Mayor to remark that “It’s going to take a better man than me to unscramble this omelet!” Then we cut over to the Sheriff’s office, where Bascomb and his son Al are yakking. Al’s now decided that he does indeed want to go to West Point. He plans to act in a fashion the town approves of until he can get his appointment. Bascomb, however, reassures him that if he still wants to be a tree farmer, he has his father’s approval.

Please, excuse me a moment. I think I…I…I must have a cinder in my eye.

There, that’s better. Bascomb gets a phone call. It’s the Mayor, warning Bascomb about the putative action at Stancill’s tonight. (I thought this guy was a Klan leader?) We must be heading for the big, blowout action climax, as Bascomb grabs his Tommy-gun and a satchel that might contain, maybe, three or four ammunition clips. Not drums, mind you, but clips. Hmm, firing at full auto that gives him a good twenty or thirty seconds of firepower.

He tells Al to go home and heads out. When Trixie, however, sees the heavily armed Bascomb leave and learns what’s up, she determines to head up to the mountain too. Al insists on joining her. Meanwhile, Stancill’s up on his mountain, telling his tenants to go home and stay quiet. Three young blacks, however, are assigned those aerosol boat horns, which they are to use as a signal when they spot the Klan guys arriving.

Bascomb shows up, hoping to keep a lid on the situation. Stancill has a line about how Bascomb could have stopped all this by arresting Cates for Loretta’s rape. (Actually, I find that an unlikely supposition, but anyway.) Burton, either extremely drunk or just really not in the mood, can barely get the line out, stuttering at least twice. I’m assuming that they reshot this, too, and that this was actually the best take.

Bascomb has a speech explaining to Stancill why he’s so hated in town, attempting to (finally) add some dimension to the film’s politics. Stancill’s policy of letting black—but no white—welfare recipients stay on his land for free keeps more of them around. Most in town believe that, without this incentive, many of these blacks would have headed north looking for work, and the money used to fund the town’s welfare rolls could have gone to better schools and such.

This, actually, is a fairly sophisticated argument, at least for this movie. And indeed, you can see how the situation would breed some at least arguably legitimate resentment, which would then be exacerbated and magnified by the area’s growing racial tensions. The only problem is that it’s a little too late for the film to try to aspire to be even two-dimensional.

In fact, the reason they haven’t raised the issue until now is so that it will be too late for Stancill to react to it. After all, if he decided to compromise, we wouldn’t get the big ending where the audience could revel in the evil Klan guys getting their heads blown off. This would obviously threaten the film’s box office potential.

Bascomb is nonplussed to see Trixie and Al arrive. He orders Al into a ditch where he’ll be somewhat safe, while Trixie tries to talk Stancill into leaving before it’s too late. Again, though, the audience must be fed it’s blood. So the air horns start blowing. It’s time.

I really find this annoying, on some level. Remember the first Lethal Weapon? Mel Gibson is fighting the evil Gary Busey to the death. However, when Gibson gets the upper hand, he spares Busey’s life. Thus does the hero prove himself better than the villain.

However, the filmmakers feared not satisfying the audience’s presumed bloodlust. So after providing the viewers proof of the Hero’s moral superiority, they let Busey grab a weapon, so that Gibson and his partner Danny Glover are forced to kill him. (This mutual shooting, by the way, is repugnantly represented as a bonding experience for our two heroes.) I personally find this kind of Have Our Cake and Eat It Too thing more than a little irksome.

If the guy needs killing, just kill him. In Dirty Harry, Eastwood intentionally taunts Scorpio into going for his gun, knowing that he has a sixth bullet left to knock him off. (The trick in the first “Do you feel lucky, punk?” scene is that Harry only had five bullets in his .44. It was often standard, in the days when cops mostly carried revolvers, to keep an empty chamber under the hammer so as to prevent an accidental discharge. This is never explained in the film, but presumably Harry loaded the entire cylinder when he knew he was going after Scorpio.)

On the other hand, if you wish to present your hero as morally superior, let him be competent enough to catch the bad guy without being forced to kill him. The one good bit in the otherwise utterly reprehensible Black Rain, the only recent American movie I can think that truly struck me as racist, is that Michael Douglas’ Dirty Harry-esque cop ultimately learns from his Japanese counterpart that there is a reason for the rules. In the end, Douglas brings in the guy who killed his original partner rather than killing him. While not really believable, given the rest of the film, it was a nice moment.

Anyway, time to throws the (evil) Christians to the (heroic) lions. Hearing the horns, Stancill sends Trixie into the house. Bascomb arms Al with a shotgun for emergency’s sake and sends him off. Trixie rings a warning bell, which seems somewhat redundant after all the air horns. The Sheriff grabs his Tommy gun and is joined by Stancill, waiting for the goons to arrive.

Seeing the Klan guys (complete in their hooded gear, to increase the audience’s enjoyment) unload up the road, Bascomb tells Stancill to cover him while he tries to diffuse the situation. Because filmmakers rarely understand anything about guns, Stancill is clearly shown to be armed with a shotgun. This is a good weapon for shooting at multiple nearby targets, but wouldn’t nearly have the range that would allow him to ‘cover’ Bascomb. That would require a rifle, preferably a semiautomatic.

Some rather bland Action Music cues us that we won’t miss out on a big gunfight, despite Bascomb’s hopes. (Duh.) The film does provide a rather silly amount of potential body bag occupants, though, as maybe twenty Klan guys head down the hill. Needless to say, we soon cut to a ‘dramatic’ shot of, yes, a burning cross. Personally, I wouldn’t want to be the lead Klan guy, approaching the house in my shiny white duds while carrying a big old flaming cross in both hands. That dude is screwed.

”Dammit, I know I dropped my keys around here somewhere. Will somebody get Harvey over here with that big cross?! I need more light!”

Bascomb tells everyone to go home, promising that Stancill will be leaving the county. Again, though, the audience presumably didn’t come to the theater to see a peaceful resolution, so the offer is laughed off as too little, too late. When Bascomb vows to fight on Stancill’s side, one of the Klansmen removes his hood. It’s Cates. They did this so we can tell he gets killed. After all, the audience will want to make sure that the lead villain gets it, and so they had to let us know that he’s in attendance.

Cates opens fire (with an M-16!) and Bascomb returns fire, hiding behind a bush (!!). Given that he’s firing at full auto, he’s presumably already expired one of his twenty round clips. From his ditch Al opens fire, also with a shotgun—and again, there’s no way he’s going to hit anything at this range. Bascomb takes advantage of this to run for cover, somehow not getting hit by any of the twenty guys blazing away at him (and they’ve mostly got rifles!).

Bascomb finally changes a clip, way, way after he would have had to. He mows down a couple of guys, but catches some (I think) buckshot. Al sees this and rushes over to his position, which I’m not sure is the most strategically sound plan. As the surrounding shacks go up, Loretta herds the frightened tenants into Stancill’s house. This, again, doesn’t necessarily seem like the best option. How about running away into the woods?

Stancill gets a guy. However, as this is a ‘serious’ movie and requires a ‘tragic’ ending, he freezes in horror at having taken a live and gets himself shot. Trixie and Loretta run over and do a bit of Oscarâ„¢ trolling grieving. Trixie, remember, was Stancill’s squeeze before Nancy hit the scene. Maybe if she knew Stancill has proposed to her—he refused to make her the same offer earlier in the picture—she’d be a little more copasetic about things.

Loretta, for her part, decides to express her grief in a slightly more proactive manner. Grabbing Stancill’s shotgun, she fires and blows a Klansman through a wooden wall. Meanwhile, in accordance with Newton’s Third Law, she herself goes flying back through the air in the opposite direction. OK, she doesn’t. But she should.

Cates and the rest of the Klan move in for a final assault. However, Garth has hidden again himself in a tree. As they pass, he leaps to the ground. I guess the filmmakers just wanted to alert us that he was around.

Bascomb jumps up and cuts down Cates. (There goes another clip.) He does this while standing in plain site, not necessarily the tactically strongest plan. For some reason, none of the other Klan guys who had been advancing with Cates shoot him in return. This allows for a ‘tense’ moment where Bascomb spots an armed Garth. The two stare each other down, but break away without shooting.

I guess that all the other Klan guys ran away. (“Welcome to Anti-Climax Theater.”) Meanwhile, Garth stumbles over a slightly wounded Klansman. He’s about to off the guy when a pistol is put to his head. It’s Bascomb. Garth fires anyway, killing the guy. Bascomb ultimately can’t pull the trigger and allows Garth to split. I find this impossible to believe. I mean, what sane person, knowing that the O.J.’s a murderer, would just decide to let him go free? It seems pretty unlikely to me.

Anyway, with that charming civics lesson for our children, we end our picture. Or…do we?

This is why I originally gave up on posting this review, even after I had finished writing the entire review. I in the end had purchased three different video copies of the film (yes, tapes…it was that long ago), because I kept seeing longer cuts of the film. The third version I got, in fact, featured a fuller and radically different version of the climax. So different was this that I walked away from the review in order to be fair to a film that had obviously been edited out of coherence in many versions.

The first version of the film I had was the most radically edited, and Stancill’s death had been excised. Thus I learned of it only when watching the second video. This inspired me to seek out a third version, the cut that now appears on the majority of the public domain DVDs out there.

During this third version, I was amazed to see that originally Lee Marvin also got killed, right at the last minute. It’s like something out of Shakespeare, assuming the Bard had been writing film scripts in the early ’70s and was really, really untalented. At this I threw up my hands, and abandoned what was basically an entirely complete review.

That was some years ago. And there’s no doubt that the film continues to suffer even in the longest cut currently available (which I believe matches the longest of the video’s, Paramount’s official VHS release). At about 103 minutes, this is still eight or nine minutes shy of the film’s original 112 minute running time.

It shows in the jagged editing in several scenes, and in the way matters like Stancill’s limp and dog are elided over. Most oddly, a lot of the violence seems to have cut out—when Garth executes his first guy, we see one shot but the fellow evinces numerous wounds. And some swearing is excised, which is especially weird given how much racial invective remains.

Still, this is version currently available, either via a downloadable version on Amazon, or via the numerous lousy DVD copies out there. As things stand, this is what we’ve got and likely all we’re going to get. Given what a lousy picture this is, coupled with the obviously objectionable subject matter, it’s hard to believe that Paramount’s ever going to lay out the money to restore and refurbish the film to its full length. And although I do feel bad about judging an incomplete film, the fact is that it seems more or less complete from a plot standpoint. In the end, this is the film now available to the public. Should a full copy ever surface, even a gray market one, I’ll be glad to revisit the picture and give it another chance. Until then, this is what we’ve got.

Oh, and not that it matters, but we never did find out who raped Nancy (at least, again, in the version that remains). I guess that it’d be racist to dwell on ‘crimes’ committed by blacks in a movie about the Klan.

Depending on which hacked-up cut of the film you end up watching, you may see one of these deaths, or both, or neither.

IMMORTAL DIALOG:

This funky theme might not be “One Tin Soldier” or anything. Still, it lays the blame for racism right where it belongs – with Christians!:

Everybody here, has some love to share,

But when it’s sharing time, we all change our mind!

It’s a slip of the lip, when you say you care,

I’ll keep my love over here, you keep yoooures over there!

All in the name of the Good Christian People!

All in the name of the Good Christian People!

(After this I was entirely unable to make out the lyrics. A blessing in disguise, perhaps?)

The avuncular Mayor Hardy, a.k.a. the Grand Exalted Cyclops, makes the following speech to his fellow Klan members. Remember kids, pigeonholing Blacks is wrong, but typecasting Christians as ignorant violent hypocrites is Right On:

“We’ve got fine Christian people here, both black and white. We’ve got great opportunity. My only interest is the orderly development of Atoka County. And none of us want a bunch of agitators, whores, punks, scum, atheists, perverts, all controlled by the Communists, comin’ in here and bothering our [grossly offensive racial slur]. The [Klan] boys at state headquarters don’t mind if you go out and burn a few crosses every once in a while. Every once in a while take an agitator out and touch ‘im up a little bit. Leave him feeling chastised, so he knows you’re his good Christian neighbors just doing what you got to do so everyone can get along!”

Finding his pooch dead, murdered (and somebody’s responsible!), Stancill reflects on when Racial Hatred goes wrong:

“Mumble mumble rednecks mumble mumble wanted to kill Charlie Peck, and Josh Franklin and all those nuns in the square. And they end up killing my dog!”

Stancill proves to be quite the smooth talking ladies’ man, as evidenced by his proposal to Nancy after she brings him breakfast in bed:

Stancill, in an exaggeratedly nonchalant manner: “You gonna keep these disciplined hours after we’re married?”

Nancy, filmed with a soft lens, impeccably made up and lit: “Married? You want to marry me?”

Stancill, holding an item from the tray: “Well, I wasn’t proposing to the sandwich!”

Sandra, a very old and dear friend of this site, has perennial problems posting comments here. In this case, her information was interesting enough to warrent including them in the actual article:

“What I wanted to say was : Count yourself lucky that in all of the prints you have seen Loretta’s ‘fate is left to our imaginations’. I saw this abomination uncut, in the movie theatre, and it stands in my mind as the single most disgusting rape scene in the history of film. I don’t know what was worse, her screaming, Cameron Mitchell’s grunts or the local minister saying a prayer as he watched. (A character in the film, I mean, not someone I was sitting with.)

I hear that Burton and Marvin were both so drunk during the making of the film that neither had any memory of making it. A couple of years later, they were both at a party and the host said ‘You two know each other, of course.’ and they both denied ever having met before.”

Given this, I am extremely glad that I was not, in fact, able to find an uncut version of the film. That scene sounds appalling enough that I’m more than willing to give it a pass.

She also asks who the title refers to, and guesses Bascomb, and I would think that is correct, although it’s never really made clear. Meanwhile, I’m pretty sure I heard of her story of Marvin and Burton denying meeting before. Whether it was because they were indeed both so drunk during filming that honestly neither remembered it–and it’s not beyond the bounds of possibility with those two–or just that neither wanted to admit any connection with this film, can only be left to supposition.

Thanks, Sandra!

A big “Jabootu Thank You!” to FoJ Roger Hylton, for providing me copies of this, not to mention quite a few other, films. Thanks, buddy!

And one more time, here’s a link to the Roundtable Supersoaker: