It Conquered the World*I Was a Teenage Werewolf*Invasion of the Saucer Men*The Amazing Colossal Man*How to Make a Monster*Earth vs. the Spider*Horrors of the Black Museum*A Bucket of Blood*Attack of the Giant Leeches*The Angry Red Planet*House of Usher*Night Tide*Pit and the Pendulum*Burn, Witch, Burn*Tales of Terror*Panic in the Year Zero*The Raven*Beach Party*X The Man with X-Ray Eyes*Dementia 13*The Last Man on Earth*Muscle Beach Party*The Masque of Red Death*How to Stuff a Wild Bikini*Frankenstein Conquers the World*What’s Up, Tiger Lily?*The Born Losers*The Trip*The Crimson Cult*Wild in the Streets*Witchfinder General*The Dunwich Horror*Count Yorga, Vampire*Cry of the Banshee*The Vampire Lovers*Blood and Lace*The Abominable Dr. Phibes*Dr. Jekyll & Sister Hyde*Raw Meat*Frogs*Wild in the Sky*Boxcar Bertha*Slaughter*Blacula*Black Caesar*The Mack*Coffy*Hell Up in Harlem*Sugar Hill*Foxy Brown*Savage Sisters*Macon County Line*Cooley High*Buck Town*The Land that Time Forgot*Friday Foster*The Town that Dreaded Sundown*The Food of the Gods*Squirm*At Earth’s Core*Monkey Hustle*The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane*The Incredible Melting Man*Mad Max*Love at First Bite*The Amityville Horror*

When AIP Films were proposed as a roundtable subject, I immediately and nonchalantly replied, “Yeah, sure.” It was, after all, a natural. AIP, the home of legendary skinflint producers Samuel Z. Arkoff and James H. Nicholson, was a notorious crap factory. Moreover, the bulk of their best know product was ’50s drive-in sci-fiers, a subgenre right up my alley.

Then the time came to actually write a review, so I (belatedly, of course) hied myself over to the IMDB and called up a list of AIP productions. Only then did the folly of my blasé acquiescence crash down upon me. Without question, AIP had over the span of three decades churned out several truckloads of pure, unadulterated cinematic cheese. Sadly, though, little of it at all was, at least by the standards of this site, well, bad. I mean, we’re talking literally hundreds of titles here. Even so, as I worked my way through the list, all I could do was marvel (and, increasingly, panic) at the unexpected dearth of turds.

Now, I’m not arguing that the company released a skein of masterpieces. Indeed, it remains incontrovertible that the average AIP flick was a lowbrow quickie shot on the proverbial shoestring. Yet within the limitations imposed by these budgets (which did grow marginally bigger as the years passed), the roster of their movies was almost uniformly surprisingly decent, and often…dare I say it?…actually pretty good. Admittedly, I’m grading on a curve here, comparing their films to similar ones made by other such companies of the time. Even so, it’s hard to get away from the fact that AIP generally produced and/or distributed titles that were consistently above the norm.

This opinion, I admit, cuts against conventional wisdom. Few film companies cared less about artistic integrity and more about the bottom line than AIP. This was the company, after all, that created a system under which they a) first came up with a saleable title, b) followed up by creating lurid spec poster art for same, and only then, if these elements drew interest from theater owners, c) commissioned an actual script and went about making a movie.Let’s give credit where credit is due, however. The fact is, when you look at the way modern Hollywood works, these guys pioneered techniques that for better or for worse rule the roost today.

Even so, barring perhaps only his namesake Sam Katzman, arguably no one in the storied history of movies (an industry legendary for its fecund crop of flimflam men) put the ‘huck’ in huckster quite to the extent that Samuel Z. Arkoff did. With his eye beadily trained upon every last dime and his trademark stogie hanging from his mouth, Arkoff remains a veritable cartoon mascot for an entire breed of poverty row producers who came on the scene (and generally just as quickly left it) back in the day.

It thus seems on the face of things downright inexplicable that this crass, purely profit-driven individual was responsible for producing and/or distributing such a slew of consistently above average genre pictures. And all together, we’re talking about roughly 500 films over a span of nearly three decades.* Clearly, Arkoff and Nicholson were doing something right.

[*To be clear, the films AIP produced there those actually made under their auspices and direct financing. A larger number of films were those that they merely distributed; in other words, movies bought or brokered from filmmakers independent of AIP and then shepherded to theaters through their network of contacts.]

This tradition of unexpected quality began in the company’s earliest days, via their association with the young but equally parsimonious Roger Corman. Corman eventually became a decent director, although I wouldn’t call him much more than that. His true genius, and I use that word advisedly, was in locating and surrounding himself with people who were both extremely talented and willing to work their asses off for peanuts just because they really wanted to make movies.

Working for Corman, both as a director and later as a producer, was akin to going through military boot camp.In either case, the only people who survived the process were the ones who were really motivated to be there. Dilettantes and divas were quickly weeded out.

Corman’s eye for talent was legendary, and justly so. However, and in a somewhat counterintuitive manner, I think his movies were so consistently and atypically good precisely because he was so focused on the dollar. Corman would use the rattiest sets and costumes if it saved five bucks. On the other hand, he never minded making a film better if it were in ways that cost absolutely no money, such as good writing, a sly sense of humor or a stock company of decent actors.

As long as such niceties never, ever impacted his, shall we say, streamlined shooting schedules and *cough* somewhat modest budgets, he was fine with them. By so completely disparaging the notion of ‘production values’ as ultimately unimportant, in an odd way Corman was able to focus on getting smart and motivated people to go to work. From there he allowed the results to sort themselves out.

That’s why he could gather all his buddies together and whip out a whimsical minor masterpiece like the original Little Shop of Horrors in literally two days and for an insanely low $30,000. In doing so, they not only made a pretty good and quite funny film, but created a framework sturdy enough to support both an long running off-Broadway musical and a film adaptation of the latter that, with a $30,000,000 budget, cost one thousand times what Corman’s film did.*

[*Fittingly, there was another big difference between the two films.Corman’s made money—indeed, with that budget, how could it not?—while the lush and to be fair extremely good musical lost millions.]

Unlike most filmmakers, it seemed entirely natural that Corman would give up being a director to become an Arkoff-like producer. Having hit his artistic peak with the AIP-produced Poe films, and then dabbled with directing for the big studios, there was nowhere else for him to go behind the camera. So he suited up and went where his real abilities lie, which involved squeezing every last nickel until it screamed for mercy.

If this sounds like an essay about Corman, that’s because that’s what I started with. My original intention was to find one actually bad movie Corman had made for AIP, and go with that. My intended subject was The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent. I vaguely remembered this as pretty bad, mostly because as a period film about Vikings and sea monsters and such it actually depended on the sort of production values Corman usually spurned.

Indeed, a quick viewing confirmed it to be arguably the worst film Corman made for AIP. (On the other hand, Liz Kingsley makes a pretty compelling case that Corman’s worst was The Beast with a 1,000,000 Eyes.) Even so, by any fair standard it remains better than you’d expect. The cast wasn’t great, but presumably under Corman’s direction the acting was naturalistic, disallowing any humorously purple performances. Well, except in one case, but that was intentional.

Yes, the women were hilariously clean and had nice hair and teeth and make-up. But hell, that would have been true if this was a five million dollar Warner Bros. Production in Technicolor. Even some of the production work was surprisingly decent. There are some good matte paintings in there, and although sets and props (like the full-sized working Viking ship, the acquisition of which I suspect motivated the production in the first place) were probably hand-me-downs from more expensive movies, well, so what? They still looked pretty good.

Having made my way about half-way through the film and with little to show for it, I was forced to throw in the towel and move on. However, this just took me back to square one. The central problem remained: Could I find a really, genuinely bad AIP movie to dissect?

The answer was somewhat obvious. If the vast bulk of the movies produced by AIP were pretty good, and even more astoundingly, even the literally hundreds of additional movies merely distributed by AIP were as well, then the mostly likely place to find a loser was at the very beginning of the film’s history, and at the very end of it. As noted, Liz went with the former, picking two films (showoff!) that in fact appeared under the banner of ARC, the company that became AIP a short while later.

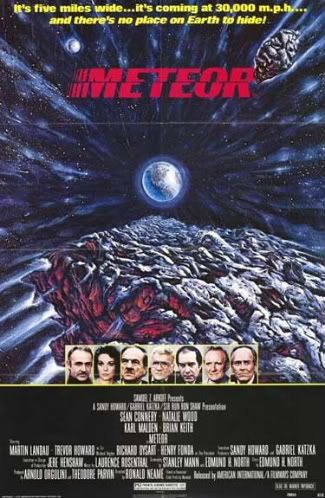

For myself, I traveled a quarter century down the line to 1979 and the film that pretty much literally put AIP out of business. Arkoff was running the show at this point, for AIP cofounder James H. Nicholson had passed away in 1972. I don’t know what persuaded him to do so, but Arkoff finally made the mistake that his protege Roger Corman never did. He decided to challenge the major studios at their own game, and make big budget movies in hopes of big returns. And so yet another showbiz legend would learn a lesson as old as the time: In the long run, the house always wins.

Note: I haven’t seen Armageddon, a film I imagine Meteor shares a lot of story elements with. The biggest difference between the two, though, is that one of them sucked and lost a ton of money, while the other one (reportedly) sucked but made a ton of money.

We begin, Jabootu bless ’em, on a black card featuring the familiar circular AI logo. We then open the film proper in space, via a shot of a comet traveling in a stately fashion directly under a fixed camera position. This image is accompanied by the opening credits (Meteor being the comparatively rare film to cite Samuel Z. Arkoff’s name before Sean Connery’s) which themselves come streaking past our view. Thus the film manages to invoke both Star Wars and Superman: the Movie within its first half minute. The only way they could write a bigger check here would be if they superimposed Marlon Brando’s spectral lips up on the screen as he whispered “Rosebud…”

As the credits continue, our hopes for big time Disaster Movie greatness begin to fade. The genre thrived in the ’70s largely based on the thrill inherent to watching, in a de-glamorized aged, the aging stars of Hollywood’s glamour era die in interesting ways. In this way, the disaster movie was the more epic stepchild of a string of popular “old psycho woman” movies of the ’60s, which afforded rather down market work for former leading ladies such as Bette Davis, Joan Crawford, Tallulah Bankhead and Olivia de Havilland.

Although many such stars opted out of such undignified shenanigans (John Wayne, Katherine Hepburn), and others made appearance in such flicks but not in roles in which they themselves perished (Jimmy Stewart), many major stars went where the lucre was, especially from the genre’s main man, director/producer Irwin Allen. William Holden, Charlton Heston, Henry Fonda, Shelly Winters, Fred McMurray, Fred Astaire and many other all served as such fodder. (Gregory Peck didn’t join in, though, opting instead to die in the disaster movie-like horror flick The Omen.)

In Meteor, though, such old-school names are all but absent.Henry Fonda is here, playing the President of the United States, but he barely counts. Fonda played an actual part, and died an actual onscreen death, in Irwin Allen’s dizzy anti-classic The Swarm. However, he also made a quick buck by appearing in a hoard of junk during this period, including several similarly lame disaster movies. For a comparatively small sum, filmmakers were thus able add a very big name to the advertising associated with the films, even if Fonda’s highlighted name in the advertising materials promised a lot more than his actual presence generally delivered.

In films like City on Fire, Tentacles, Meteor and Rollercoaster (!), Fonda basically functioned as a very expensive day player. His scenes were usually so self-contained that he often didn’t even interact with the rest of the main cast. This allowed filmmakers to shoot his scenes in very quick order, often on one or two conjoined sets, and later intersperse those scenes throughout the film. As such, Fonda’s general role in these pictures was as an on-looker.

For his part, Connery was a pretty traditional choice of a big name but younger actor (Gene Hackman in Poseidon Adventure, George C. Scott in The Hindenburg, Richard Harrison in Cassandra Crossing, Newman and McQueen in Towering Inferno, Michael Caine in The Swarm, etc.) who played the respective movie’s more involved lead character. The older folk, as noted, tended to be sacrificed, but these guys generally made it through.

Even Connery didn’t count as a Paul Newman or anything. Connery continued to ride the good will generated by his having played the most iconic James Bond, even if he himself increasingly came to disdain the role. However, since abandoning the part (for the most part) after 1971’s Diamonds Are Forever, it’s amazing how few really major films there are in Connery’s filmography. While there aren’t a lot of Zardozes, there aren’t a whole bunch of The Man Who Would Be Kings, either. So Connery was still a big name, and a definite headliner, but not necessarily a top tier, A-list star.

And after Connery, the rest of Meteor‘s ‘star’ cast proves pretty weak tea. The next name to appear is that of the ill-fated Natalie Wood. Ms. Wood herself had once been one of Hollywood’s brightest. She started as a busy, much beloved and eminently adorable child star in movies like 1947’s Miracle on 34th Street. Orson Welles once played opposite her when she was but seven. Decades later Welles described her as having been “so good, she was terrifying.”

Unlike most of her child peers, Ms. Wood beat the odds and made a markedly successful transition to adult acting work. At the tender age of 16 she starred opposite James Dean in the 1955 classic Rebel Without a Cause. Six years later she landed her most iconic role as Maria in the incredibly popular Best Picture winner West Side Story. By the age of 25, Ms. Wood had already been thrice nominated for acting Oscars.

By 1979, though, the bloom was definitely off the rose. Ms. Wood continued to be fairly popular throughout the ’60s, but in the ’70s more or less entered semi-retirement. Indeed, previous to Meteor she had appeared in only one theatrical film during the previous ten years, and that was the enjoyable but minor private eye pastiche Peeper (1975) opposite Michael Caine. Other than that she spent the decade doing a smattering of television work. In other words, Ms. Wood’s name on the marquee was not exactly likely to draw in the kids who made Jaws and Star Wars huge hits.

Even so, the period immediately following Meteor indicates Ms. Wood was ready for regular film work again. In 1980 she starred in The Last Married Couple in America, a romantic comedy opposite George Segal. She then began work on a fairly high profile sci-fi picture called Brainstorm opposite Christopher Walken. Indeed, she had two more projects lined up after that.Brainstorm, however, sadly proved her last movie.

In the midst of production on that picture in 1981, Ms. Wood died in a tragic drowning accident. She was 43. This left the makers of the largely, but not entirely, completed Brainstorm in a fix. It was a couple of years before they managed to shape what footage they had into a quickly aborted release.

Back to the credits. So basically we open with Sam Arkoff, move rapidly up the ladder to Sean Connery, followed by the still well-known Natalie Wood. And then flying past the camera come the names of…Karl Malden and Brian Keith. These are not monikers that likely induced gasps of excitement from theater crowds. Both men had done film work, but by this point were basically known as TV actors. However, we do get a credit noting said thespians are appearing “in a Sandy Howard/Garbriel Katzka Sir Run Run Shaw Presentation.” So there’s that working for us.

Hilariously, if fittingly, given Arkoff’s history, we then move on to an Unseen Narrator (he sounds like he’s imitating Sir Cedric Hardwicke’s opening spiel from 1953’s The War of the Worlds) declaiming stuff about comets over shots of stars and galaxies and such. These include a shot of a huge fireball blossoming right in the middle of space, although I’m not exactly sure how that would work. In any case, this opening thus evokes nearly every cheapie sci-fi flick of the ’50s. Not how I’d start my hugely budgeted ’70s epic, but there you go.

“At first comets terrified Man,” the Narrator explains. “He thought they were signals of impending catastrophe.” And for movie ticket buyers in 1979, these omens proved entirely correct. (Thank you, ladies and germs! I’m here all week.)

Eventually, however, Man—so the Narrator informs us—became comfortable with these celestial visitors. Then we cut to the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. The Narrator draws our particular attention to the massive Orpheus, “20 miles in diameter, and undisturbed for countless generations. Until now….”And, cue music blare and title card.

Following this, we then get a weird animated image of a racing yacht seemingly sailing across the starscape. This transitions to a shot of a real boat sailing upon normal waters. Further names appear over shots of this craft plying the briny deep, and these mostly continue to be TV actors: Martin Landau, Richard Dysart, Joseph Campanella. I mention this because there used to be a much bigger ‘caste’ difference—ha ha!—between TV and movie actors than there is now.

There are a few actual film actors mixed in there as well.Well known Brit character actor Trevor Howard (“as Sir Michael Hughes”) is on hand to class up the joint a little. And the last such credit, naturally, reads “and HENRY FONDA as The President.” Even so, hardcore b-movie fans might want to peel an eye for brief appearances by Bibi Besch and Sybil Danning (as “Swiss Girl Skier”). Sadly, however, this elite audience demographic wasn’t robust enough back in the day to ensure the film a profit.

Anyway, the yacht is being steered by none other than scientist Dr. Paul Bradley (Sean Connery). However, his hopes for racing glory are cut short when his craft is intercepted by a Coast Guard patrol. “We’ve got orders from NASA” (!) a fellow explains via megaphone. Who knew NASA had such authority over the Coast Guard? NASA’s orders are to grab Bradley and get him on a “special flight to Houston.” Bradley proves a surly cuss, but after the cutter threatens to cut across his bow he angrily heaves to.

This, a card informs us (using the jagged font employed for the movie’s title), occurs on “Monday.” And so the traditional Time Element is started. Bradley later asks a Coast Guard guy if he really would have cut in front of his bow. The fellow replies that he would have, and Bradley snarls, “Then I would have rammed you!”(!!!) The guy calmly replies, “And gone straight to the bottom, sir.” Bradley reacts to this statement by thrusting his head out the window of his departing car and assuming an irate “Why, you!” expression. This struck me as an odd reaction. You’d have to think that in any ramming contest, a racing yacht would probably lose to a Coast Guard patrol boat.

Cut to NASA HQ in Houston. Bradley enters an office and banters with a secretary, which may be a wink at his scenes with Moneypenny in the Bond films. However, his sour disposition returns when he sees his own packed travel bag sitting in a nearby chair. A quick line soon establishes (and I must admit I actually groaned when I heard this) that the bag was provided on request by…wait for it…Bradley’s inevitable Estranged Wife, Helen.

The apparently permanently piqued Bradley then enters the inner office of NASA official Harry Sherwood (Karl Malden), a man he once worked for. (As I detailed in my 10.5 review, “Everyone is connected.”) Also on hand is General Easton (Joe Campanella). Sherwood attempts to placate the ornery Bradley with a tale told in flashback form.

Recently, a rogue comet (the one seen at the beginning of the film) was detected heading towards the previously cited asteroid field. Luckily, a manned Mars probe was on hand. Sherwood diverted it from its planned mission to place itself in viewing distance of Orpheus and report on the comet’s doings. Standing by in the NASA Control Room during all this is Gen. Easton, as his son just happens to be commanding the probe. (Everyone is connected.)

You don’t exactly have to be Nostradamus to figure out that comet hits Orpheus and blasts in into smaller, but still sizable, chunks. One particular fragment, naturally, takes out the probe in a welter of truly bad special effects. Given the film’s budget they must have spent a batch of money on the f/x work.Even so, audiences fresh from Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind could not have reacted to the sequence’s comically inept matte and composite shots with overmuch kindness.*

“Help! Our spacecraft is being destroyed by a meteoroid! And this is exactly what such a thing would look like!”

[*On the other hand, the physical model work is pretty elaborate—this being before practical CGI—and the spacecraft are really meant to look logically designed rather than ‘cool. ‘The fact remains, though, that some of the matte shots are just hideous.]

The destruction of the Probe isn’t the half of it. One giant chunk of Orpheus, along with several large ‘splinters,’ survived. These, naturally enough, are now on a direct collision course with Earth.

For his part, Easton bears up to the tale with the expected stiff upper lip. I have to admit, I found myself amusedly mulling the possibility that Sherwood had Easton on hand to negate Bradley’s apparently natural surliness. It’s surely bad form to bitch about stuff when you’re sitting opposite a man who a few days earlier had listened to his son being pulverized to space dust.

Anyway, there’s to be a meeting in Washington with the Secretary of State (Richard Dysart) and various bigwigs. Bradley angrily refers to Project Hercules, and Sherwood agrees, saying that this is why he wants Bradley to attend the meeting too. He reluctantly agrees, and Sherwood explains how all the arrangements for his flight and lodging have already been made. “Why don’t you stick a broom up my ass?” Bradley snarls as he leaves. “I could sweep the carpet on the way out!” That’s not up there with Connery’s classic threat from Just Cause, “I’m going to play your ass like a banjo,” but it’s pretty good.

We cut to Bradley arriving at his hotel room, which sports a typically hideous ’70s paisley bedspread. Inside he finds a note from Helen, and sighing, calls her. Here we learn that she is played by Bibi Besch and not Natalie Wood, so apparently reconciliation is not in the cards. They chat, you know, like folks do, and we learn that she obviously still has feelings for him, and that they have kids, and anyway get to know them as people, so that we care. Man, I’m so invested in these characters now I could spit.

By the way, as it turns out, this is Besch’s only scene. So, you know, why even bother?

In a tiresomely arty shot, we transition from the room’s abstract, spaceship-like light fixture to the armed space platform Hercules. Bradley pictures this in his head (I guess), and also Orpheus as it tumbles through space. The musical score booms over these images, thus allowing us to figure out that they’re ‘exciting.’

The next morning we get a card reading “Tuesday,” or five days before Orpheus will collide with the Earth. Bradley drives through Washington for the aforementioned meeting. However, when he arrives at the designated room, he learns that he is meeting solely with Sherwood. This scene is pretty pointless, except that it allows the two to yell at each other a lot—it’s called ‘dramatic tension,’ folks—while they also lay out Bradley’s backstory for audience enlightenment.

Sam Arkoff reads over the box office reports for Meteor’s opening weekend.

Bradley, we learn, left NASA five years ago.He had worked on Hercules, a highly secret space platform armed with nuclear missiles. Said warheads were intended to protect Earth from exactly the threat that Orpheus now poses. Not to shock the hell out of you, but Hercules was *gasp* co-opted by military Neanderthals and is now instead pointing its missiles at the Russkies. Naturally, Bradley was shocked and outraged by this eee-vil misuse of his project, and he resigned.

The solution seems simple enough: Reorient Hercules and fire its missiles at the approaching Orpheus. The problem is the U.S. has never revealed Hercules’ existence,* since it violates every nuclear arms treaty the government has every signed. Rather than expose the government to International derision and ridicule, many would rather take the chance that Orpheus will miss the Earth and just fly on past.

[*Really? The U.S. built a gigantic space platform, one orbiting the planet and loaded with a dozen nuclear missiles, and nobody ever noticed?]

Cut to Mother Russia, where the film reveals its entirely predictable and ham-fisted moral equivalency. For here we meet Bradley’s counterpart, Dr. Alex Dubov, although as played by Brian Keith he is inevitably a big, friendly Russian bear of a man. You can begin the clock now on how long it takes for him to call somebody “tovarich” and be seen swigging vodka.

Dubov is himself explaining the facts about Orpheus to his own collection of humorless government drones. By the way, if you’re wondering if they are walking around outside in the snow while wearing big fur hats, well, yes. Yes, they are. “It would take our friend up there two seconds to turn half of Russia into one huge Siberia,” Dubov asserts. Bonus points for Keith, by the way, for actually performing his role in Russian. He was already fluent in the language, which no doubt helped him get cast here.

Dubov proves that Scientific Integrity knows no borders when he suggests to his colleagues that they try to contact NASA. Meanwhile, his government minder is informing his fellows that such contact must be prevented until the Chairman makes a decision.

At this point we cut to the aforementioned meeting in Washington. Exactly like Dubov’s minders, the Secretary of State is ordering that no one reach out to the Soviets until the President says to do so. See, there’s really no difference between their politicians and military and ours. Nor in the scientists, either, who are predictably the only ones enlightened enough to actually place a premium on, you know, saving the Earth.

This facet of things starts getting beat to death at this point. Among those in attendance is the man who seized Hercules in the first place, General Adlon. The film makes a half-hearted stab to avoid casting Adlon as an outright villain, by having Sherwood earlier describe him as “a good man, technically, but he’s two dimensional.”(??)

Any such nuance is immediately belayed, however, when we actually meet Adlon. He is played by Martin Landau going full tilt boogie with his trademark Creepy Spaz routine. Moreover, he is made to spout a completely ridiculous position, which is that they can’t reveal Hercules’ existence because then the international community would call us liars just because, you know, we’ve been lying.

In contrast to Adlon’s mendacity, Bradley is all Righteous Fury and Sherwood all Reason & Humanity. After this little bit of Kabuki theater plays out, the Secretary breaks up the meeting and leaves to consult with the President. Bradley and Sherwood head over to a nearby bar where they await the President’s decision. A regular bar because, you know, except for being smarter than everyone else in the room they’re just average joes.

In any case, the cat’s out of the bag. The bar’s TV is showing a BBC report detailing how British astronomers have caught sight of the approaching Orpheus. Gee, who would have thought anyone would notice that? The reporter explains what a dire threat Orpheus may pose, but the crowd yells for the bartender to switch over to a football game. I guess Bradley and Sherwood really are smarter than everyone else in the room.

Sherwood begins this boring anecdote about how he snuck his son to get emergency medical care in order to get around his fretful wife’s objections. In the end, despite her fears (“she can’t stand the thought of an operation”), she was glad. Apparently this is Sherwood’s way of telling Bradley that, if it comes to it, he will (somehow) sneak Bradley into Hercules Control so that he can use it against Orpheus. This idea is so retarded that the script doesn’t go in that direction, but please, how the hell would that work?

Sherwood gets a call, and he and Bradley leave to confer with The President (Henry Fonda), along with the Secretary of State and Gen. Adlon. Being the sort of movie this is, they never bother giving Fonda’s character a name, because, you know, he’s just The President. Fonda thus actually interacts with some of the main cast members here, which is more than he does in a lot of other films he made at the time. Even so, I suspect his scenes were again designed to be shot in as short a time period as possible.

“You’re paying me in cash, right? No checks. That was the deal!”

I can only wonder what Fonda thought about the whole Hercules angle.He had fifteen years earlier used a lot of his personal muscle to get Fail-Safe (1964) made, in which he played a President facing a possible nuclear war with the Soviet Union.* Unsurprisingly, this was a big message piece about the dangers of the nuclear arms race. Given this, you have to think it didn’t exactly please him to now play the President in a movie about using nuclear arms to save the Earth. I think this more than anything else shows that Fonda was all about the paychecks at this point in his career.

[*It was to Fonda’s misfortune that Fail-Safe hit theaters nine months after Stanley Kubrick’s nearly identically plotted black comedy Dr. Strangelove came out. Indeed, both films were released by Columbia Studios, which seems pretty stupid. In any case, Fonda’s entirely earnest film couldn’t hope to compete against Kubrick’s darkly comic sensibility, one that somehow seemed a much more appropriate approach to the issue at hand.]

Sadly, there’s more bad news. Even the somewhat smaller Orpheus is still too massive to be destroyed by Hercules’ missiles. Sherwood asks The President to confirm that the Soviets their own secret weapons platform, and of course they do. The only way to destroy the meteor is to use the missiles from both platforms in conjunction. After all, otherwise we in the audience wouldn’t learn a lesson about how people have got to work together to save this crazy old world of ours. (Of course, currently there is no more Soviet Union, so I guess we’d be screwed.)

The President listens to the facts and, to the displeasure of Gen. Adlon, agrees to use Hercules. He moreover puts Bradley in charge of the operation, thus exactly paralleling how Michael Caine’s scientist is given authority over suspicious military man Richard Widmark in The Swarm. We cut to a press conference.The President reveals Hercules’ existence, but under the guise of it being solely designed to destroy dangerous meteors.*

[*This movie must have driven scientifically minded nerds nuts. First of all, before a meteor enters a planet’s atmosphere, it’s technically a meteoroid. However, meteoroids are by definition fairly small. Given Orpheus’ gigantic size, the proper designation should still be asteroid, but I guess they didn’t think that made as good of a movie title. Still, the word ‘meteor’ continues to be so misused throughout the film.]

Cut to the Kremlin, where Soviet muckamucks are also watching the conference. In an attempt to force their hands, The President reveals that the Soviets also have built their own entirely peaceful armed space platform. He announces he will be asking them to join with the U.S. to deal with the current problem. Following the conference The Chairman turns to his underlings, including Dr. Dubov. “The Americans have elected an alchemist,” The Chairman observes. “He can turn hypocrisy into diplomacy.”

He explains that they will pursue discussions on the matter, but cautions that these are to remain only discussions. Dubov, of course, is as jaundiced about such thinking as Bradley and Sherwood on the other side. Then, as The Chairman predicted, the Hotline immediately rings with a call from The President.

“Wednesday” We cut to a shot of New York, which naturally includes the now creepy (especially in context of this film) World Trade Towers. Bradley and Sherwood arrive in the lobby of the fabulous AT&T Building. It turns out that the nation’s most super-secretest and important emergency response center is located directly below.

Bradley is askance upon hearing this, but Sherwood proffers the notion (if not in so many words) that putting it under our busiest [and hence most likely to be attacked] city is so moronic that it’s brilliant. You see this sort of thinking in movies all the time, and hopefully it’s mainly confined to them. Moreover, since they’re now planning to reveal the entire set-up to a team of Soviets, well, I hope they have a spare one somewhere.

As you’d assume, we’re talking a big underground control center here, of that sort that must have felt like home to Connery after all those Bond movies. They meet with Adlon, who’s still kind of bitchy. He immediately complains about the idea of letting the Russians into their most top-secret emergency control center,* which naturally the film treats purely as an indication of his sadly limited, two-dimensional thinking. I notice, though, that the Soviets aren’t throwing open the doors of their main command center.

“And it was only after we’d constructed all this that we were like, ‘Dude, we totally forgot to save any money for the special effects stuff!‘”

[*The same thing happens when Peter Sellers’ President invites the Russian ambassador into The War Room in Dr. Strangelove. One reason that movie remains so relevant today is that despite having similar complaints lodged by a forthrightly buffoonish counterpart to Adlon, said ambassador does in fact spend his time trying to take spy pictures of the set-up, even in the face of an imminent nuclear holocaust that threatens to destroy both countries .Needless to say, such a jaundiced view of things will not be on display here.]

In the Center, Bradley gets a video call from Sir Michael (Trevor Howard), presumably the Brit astronomer who somehow managed to notice Orpheus barreling towards the planet. Connery asks for an update on the asteroid’s progress, I guess because we don’t have any observatories here in the United States. Sir Michael informs him that some smaller but still devastating splinters of the original Orpheus will hit in 24 hours, with the main asteroid still set to hit in three days.

That evening the Russian delegation arrives in Washington, lead by Dubov and his pert interpreter, Tatiana Nikolaevna Donskaya (Natalie Wood, natch). Because, you know, that’s the sort of name those wacky Russians have. And so, a mere thirty-six minutes into the picture, we finally meet our female lead. Sherwood is on hand to greet them, and presumably to take them to New York.

”He said he knew who we were by our huge fur hats.”

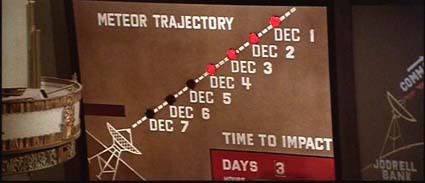

“Thursday” A big if extremely stupid-looking sign is set up, noting both “Meteor Trajectory” the number of days—now 3—until impact. Again, you’d think the scientists would get the whole ‘asteroid’ thing, but I guess not.

“Oh, that? Yeah, the mission commander’s kid made it, and his wife wouldn’t stop nagging him until he put it up there.”

Dubov is meeting with Adlon (why?). In a bit I can only deduce is meant to be funny—despite the direct evidence to the contrary—Tatiana and Adlon’s own interpreter talk directly over each other whenever Dubov says something. I don’t know, isn’t there protocol for that sort of thing? Wouldn’t Adlon’s man translate what Dubov says, and Tatiana translate for Dubov what Adlon says?

Because he’s a boneheaded military guy who narrow-mindedly hates Russkies, Adlon refuses to answer any technical questions about Hercules, and suggests they get such info from Bradley. This is dumb, and nobody so high up in the real military chain of command would be this stupid.* He knows Bradley would give Dubov the information anyway. Furthermore, he was there when his Commander in Chief personally put Bradley in charge.

[*OPEN SPACE FOR FORTHCOMING SANDY PETERSEN REJOINDER.]

Given this, his actions here constitute mere petulance and are therefore completely unbelievable. And why is Adlon even meeting with Dubov, then? Predictably, Landau plays the scene via a continuous series of exaggerated sneers, grimaces and hostile body language, acting like a teenager whose been told he can’t go to a friend’s co-ed slumber party.

Bradley and Sherwood enter, and the Translation Twins kick in again. When Bradley complains about the stereo effect—it’s not nearly as adorable here as when the Twin Fairies of Infant Island do it—Adlon replies that it’s “recognized procedure.”(!!!) “How else do we know if we’re being translated properly?” he grumps. Uhm, I don’t know, by having the other translator in the room but not speaking unless he hears his counterpart mistranslating things?

Now that we’ve (again) established that people in the Military are complete maroons, we can (again) establish that scientists are commensurately level-headed and open minded. You can imagine Adlon’s reaction when Bradley answers his question by saying, “I think we can all start by, uh, trusting each other.” Burn!! Take that, fascist! Being a big baby, Adlon immediately splits in big huff and spitefully takes his own translator with him.

Bradley has no trouble with this, although for some reason this isn’t meant to portray him as a complete idiot. I mean, leaving only the Russian translator hardly seems optimal to me. But then, I’m also the sort of paranoid dunderhead who leans toward the whole “trust, but verify” approach. For his part, Bradley would prefer not to harsh anyone’s vibe with such stuff, because just “trust” is so much groovier. Also, he immediately gets busy flirting with Tatiana. Hey, they’ve got three days before the world is due to get annihilated.

We’re currently in the dreaded ‘treading water’ phase of the film. As such, we basically just go over the same stuff—military guys dumb, scientists caring and reasonable—over and over until we burn up enough time to start the mass destruction.

The film does make a nod at Keith playing it cagey about the existence of Peter the Great, the Soviet analogue to Hercules. However, his heart clearly isn’t in it. He quickly agrees to spill the beans as long as it’s understood that he’s only talking “theoretically.”

Tatiana, who in real life would ‘secretly’ be Dubov’s KGB minder and in constant contact with agents in the Motherland babysitting any family Dubov had (and if he didn’t have any, he wouldn’t be allowed to leave the Soviet Union in the first place) doesn’t blink an eye at this.

“Friday” Two days to go. We cut to a night and snow-shrouded Eskimo abode.An Eskimo chap just returning home looks up to the sky and sees a big red light over the horizon.He shrugs and enters his family’s tent. Seconds later, though, he is shocked to see what looks like daylight streaming in through the tent’s wide open flap. (Yes, that’s how I would keep things heated in there.) Said illumination, unsurprisingly, emanates from an oncoming blazing meteor. Yes, now it’s a meteor. He calls his wife, and she is similarly agog at the sight. Soon massive winds kick in and the meteor hits behind a nearby mountain.

“For the love of Pete! I already sang ‘Tiny Bubbles’ three friggin’ times!”

Cut to the UN, where it’s explained that this occurred in Siberia. Of course it did. The movie needed a strike actually in Russia to explain why the Soviets would suddenly get serious about helping out with the American plan to destroy Orpheus.

Back to Hercules Command, where we learn that two minor characters are lovers. Again, wow, now I’m like totally invested in what happens to them.Shrewdly played, screenwriters Stanley Mann and Edmund North. (North wrote the screenplay for the original 1951 version of The Day the Earth Stood Still, another film that offered wise scientists of many countries putting politics aside for the good of Mankind, in counterpoint to overly dumb and violent military personnel.)

Anyway, apparently it’s now officially the ‘character’ part of the film, since (again like Michael Caine in The Swarm) Bradley takes time from attempting to avert an impending apocalypse to mack on a pretty girl. To be fair, though, unlike Caine and his sweetie Bradley and Tatiana don’t decide to take the afternoon off and tool around in a van. Instead, we learn Tatiana’s backstory, which proves quite lengthy if rather less compelling than I assume the filmmakers had intended.

Thankfully, we eventually cut to some prospective mass destruction and death (finally!) as a swarm of meteors appears over some completely unconvincing “European” locale(s). I assume this is meant to be France (one beret-clad fellow is seen making out with a woman). Sadly, though, this all proves a false alarm. The meteor shower burns up in the atmosphere without destroying anything.

In response to this harmless shower, Adlon screamingly announces to the entire control center that, in his opinion, the whole crisis is clearly a tempest in a tea storm. I mean, if these little shards all burned up, surely the five-mile in diameter main body of Orpheus will too. Seriously, are we supposed to take the film seriously when it continuously posits Adlon to be such a complete jackass? I’m not kidding, Adlon goes into utter melt-down here. I’ve seen Yosemite Sam react to Bugs Bunny with more restraint.

And even if Adlon were absolutely correct, so what? He’s received orders directly from The President of the United States. Until those are officially rescinded, he’d still be under Bradley’s direct authority. I don’t think moviemakers really get how invested the military is in the whole chain of command thing. Adlon finishes up by stalking out of the command center, vowing that when the President restores his command, “I shall return!” Ha! It’s a MacArthur reference. How droll.

For some reason Adlon’s tirade sets off an answering one by Dubov. However, Dubov’s (I guess) is presumably meant to be comical, given that it’s punctuated by wacky stereotypic Russia Music. This ends with him calling the Russian Embassy to suggest that they indeed begin working with the Americans. Wow, Adlon’s inanity resulted in exactly what he most feared; America and Russia working together. Oh, the Irony.

For some reason, Dubov’s vote changes things. (Personally, I’d say a meteorite strike directly on Russia would not only make more sense as a motivating factor, but be a lot more entertaining. But then, I have a petty dislike of Communist states.) Thus at the UN the Soviet representative officially reveals the existence of Peter the Great, and announces that its missiles will indeed join those of Hercules to destroy Orpheus.

As a mild jape regarding Soviet grandiosity, the Representative makes sure to emphasize that Peter the Great was made before Hercules. Sadly, though, he doesn’t say “wodka” or anything like that.

Humorously, no sooner had I typed that then we cut to a close-up of a vodka bottle. Bradley, Dubov, Tatiana and Sherwood raise a glass to having successfully jumped the political hurdles. (Well, actually, they toast Peter the Great…but not Hercules.I guess it’s kind of a prodigal son sort of deal.) Dubov then ‘comically’ imitates a cab driver he once had in New York, offering in his thick Russian accent the toast “F*ck the Dodgers!” Oh, my sides.

This is the point where the film perhaps misconstrues exactly how absorbed we in the audience would become. I suppose if you were really buying all this, and really lost in the idea that the very Earth was imperiled, and rapt over the irony of how Man was about to turn his mightiest weapons of destruction to the task of saving the world, and moreover, in how two bitterly inimical superpowers who had (in the view of many) held the entire planet hostage for decades were now finally converting said weapons into plowshares—albeit the sort of plowshares capable of decimating a giant asteroid—well, the following three minutes plus spent watching the weapon platforms being slowly realigned, all while the folks in the control room look on in awed, silent wonder. In such a case, I guess this could have indeed struck such hypothetical moviegoers as the veritable knees of the bees.

For the rest of us, though, it’s an excruciating, interminable borefest. For those of this latter persuasion—a much more substantial cohort, I would think—the misery is alleviated only during those sublime moments when the light hits the slowly rotating models of Hercules and Peter the Great just right and we see that the markings on the various respective missiles are not painted on, but are in fact quite obvious decals. It warmed my heart to see this again, because frankly said decals were the sole memory I had of the film from seeing at the Des Plaines Theater back in the day. (Sadly, I can’t remember what its double feature partner was. However, one time at that same venue I saw a twin bill of Thank God It’s Friday! and When a Stranger Calls.)

Anyhoo, the sequence rolls on in all its presumed majesty. There’s no doubt the filmmakers considered this scene to be a genuine showstopper. And to be fair, in a certain sense, it really, really is. However, even this must eventually pass. And so a note of *cough* tension is introduced when it’s announced that Hercules isn’t aligning quite the way it should be. They transmit a software patch and…it works! It works so well, in fact, that there then follows yet another straight minute of the HOT! ALIGNING! ACTION! that everyone in the audience was no doubt desperately craving at this point.

At this point, we’re about an hour into our roughly one hour and forty-odd minute movie, and some may have begun to notice that for a disaster film our feature has been, well, lamentably free of disaster so far. I don’t know, a cartoon meteorite scaring some Eskimos just might not be enough to assuage the vulgar sensibilities of some. And so we cut to Switzerland, where we see a young and barely recognizable Sybil Danning as the appropriately indicated “Swiss Girl Skier.”

SGS skies a little, then comes into town and walks around a bit.She greets some passersby, joins friends in a cafe, and so forth. After a minute or two of this—which would be much more entertaining, I must admit, were Ms. Danning more typically clad in a bathing suit (or birthday suit, for that matter)—we cut away to take a very quick look at a cartoon ball of light striking a nearby peak.

This triggers an avalanche and, finally, we are treated to some of the lovingly detailed mass death and destruction we all came here for. Dozens fall victim to the crushing snow, and an entirely town is buried. Except…except…except that, damn, this all seems familiar somehow.

And so should it be, because pretty much all the special effects here had been lifted from Roger Corman’s own production of Avalanche, starring Rock Hudson and Mia Farrow and released the year before this. I confirmed this suspicion by watching the trailer of Avalanche posted on YouTube, which sure enough featured many of the exact same effects shots.

As it turns out, this will prove Meteor‘s longest and most elaborate special effects sequence. And again, it was lifted from a film in the exact same genre that had just been released to theaters a year earlier! Good grief, Arkoff, where did that vaunted 16-20 million dollar budget go, anyway? And remember, this was in the days before made-for-video movies or anything of the like. Theatrical films were pretty much the only game in town back then. Meanwhile, you’d have to think that anyone likely to buy a ticket to see Meteor was also likely to have seen Avalanche the year before.

Still, if you ignore that (or reap from it the proper amount of gobsmacked amusement at Arkoff’s audacity), well, at least it’s the sort of thing we came here to watch. Hell, even the four-plus minutes of model space platform rotation was better than spending more time with the film’s ‘characters.’ So if nothing else, at least the movie is becoming marginally more entertaining. Still, I kind of wish Arkoff had gone whole hog here and cut in sequences from, say, Earth vs. the Giant Spider. I mean, as long as you’re lifting stuff, why stop with Avalanche?

Sadly, Swiss Skiing Girl and her boyfriend were doomed from the moment that each neglected to bring along their package of Mentos.

The disaster is soon being reported to a horrified world. In another memorable moment of cheek, some mass ski race stock footage is cut in as a reporter announces that “the tragedy has been heightened by the loss of 12,000 contestants in the cross-country marathon which started from Maloya only an hour before the [meteorite] splinter hit.”Gee, 12,000 skiers killed by a gigantic avalanche? I don’t know, that might have actually been even more entertaining if we had seen it rather than just heard about it.

Meeting with The President—who reacts to the news report with a very Henry Fonda-ish “Myyyy God!”—Sherwood explains how the missiles are to be used to destroy Orpheus. In two days, as it approaches the planet, they will trigger Peter the Great’s missiles. Forty minutes later, Hercules’ missiles will be sent.Given their relative positions, this should mean that the missiles team up before reaching Orpheus about two hours out from Earth and strike the asteroid in three waves.

Anyway, sadly, it’s now time to get back to that high-powered cast they apparently spent all their money on. In her room, Tatiana is gazing with pleasure in the mirror, having donned a scarf given her by the women who we earlier had seen with her boyfriend. Hmm, otherwise pointless character who we glimpse very briefly, who we’re shown has a lover and who moreover very briefly makes friends with one of the movie’s stars. Gee, I wonder what will happen to her before the movie’s over?

Tatiana leaves the room meets up with Bradley.He compliments her on the scarf as they head to the cafeteria for a bite and more of the yakity-yak. So that, you know, we get to know them as people. People who need people. They’re the luckiest people in the world. Sadly, though, not apparently the most interesting people in the world.

So let’s move on. I mean, seriously, we all have better things to do, right? In fact, the only thing is that some might find even remotely interesting in this part of the movie are the cafeteria’s Space Odyssey and Skylab pinball machines.

Sadly, further fascinating peeks into Bradley and Tatiana’s interior beings are preempted by a video call from a scientist in Hong Kong. He reports that another splinter had smashed into the nearby ocean, nearly downing a passing airliner. (Hmm, something else that arguably might have been more interesting to actually see.) As a result, a huge tidal wave is about to engulf the city.

There follows several minutes of impressively elaborate panicking crowd scenes, followed by at some short but fairly decent f/x shots as Hong Kong is inundated.

The sequence basically revolves around one guy forcing himself through the fleeing masses. He eventually reaches his apartment and scoops up his wife, their son, and as an afterthought, their dog. (Box lunch, I guess.) Then they continue fleeing until it’…too late! Oh, and there was one shot that demanded I give a shout out to my old friend Andy Borntreger:

1:10.50:GRATUITOUS ZOOM SHOT OF A COCKATOO!

Given that the avalanche stuff was all lifted from another movie, my initial reaction to this sequence was to assume it was similarly borrowed from some Asian disaster movie, maybe 1972’s The Submersion of Japan. I mean, the crowd scenes especially are well beyond anything else the film has yet provided us on its own.And when the scientist talking to Bradley is killed, he clearly turns into another guy entirely just as the water hits him.

Then I remembered that the film was co-produced by Run Run Shaw. Perhaps his contribution was a preexisting sequence from an Asian disaster film he had already made or had the rights to. On the other hand, extras are a lot cheaper over there, so it’s entirely possible that he actually shot the footage fresh for this movie. (Imagine. What a concept.)

And the doomed scientist who briefly turns into another guy? Footage from two movies spliced together, or just a classic case of bad stuntman substitution? We may never know. I’ll tell you one thing, though. If Run Run Shaw did make this sequence, I wish they’d have just given him all the money and let him make the whole friggin’ picture.

It’s about time to launch the missiles, so we cut down to the control center. Things seem to be going well, although the level of computer graphics on display aren’t overly reassuring. We get thirty-plus seconds of countdown to Peter’s missiles being launched, because hey, there’s running time to eat. The plastic nature of the missiles isn’t entirely disguised, but really, it’s not a bad sequence, all things considered.

After the missiles are on their way, Adlon comes in and apologizes to everyone for being such a dunderhead. It’s not a bad moment, but it probably means he’ll be ‘tragically’ killed later.

Then it’s time for Hercules’ missiles to launch. However, we need more drama (there’s half an hour of movie left). So Sir Michael phones from England and reports that they’ve sighted another splinter—uhm, what, no American observatory has noticed this yet?—and it’s *gasp* headed right for New York City.

Wow, what are the odds that, out of the entire world, the last splinter would strike directly over the location of the control room? I’m no statistician, but I’m betting at least ten to one against. Oh, and when is this due to happen, Bradley asks? “Just about…now,” Sir Michael replies. But he’s kidding. There’s actually like two or three minutes left.

Now everything hinges on whether they can launch Hercules’ missiles before the huge splinter strikes and knocks out their capacity to do so. Because, you know, if you build the top secret control center for your space-based nuclear weapons platform right under downtown New York City, you want to make it so that were the control center destroyed the platform would be rendered completely unusable.

Not to blow it for you, but they just manage to get the missiles off before the cartoon splinter strikes the city. (It’s a close thing, though, mostly because the launch is so freakin’ long.) In a nauseating shot, albeit that’s hardly the fault of the filmmakers, it smashes through the Twin Towers. Aside from that, though, the sequence is done entirely on the cheap, consisting of a few matte paintings and several inserts of what is clearly stock footage of several real life building demolitions.

Meanwhile, they introduce another complication for, you know, the suspense. As Peter’s missiles make their way, a couple of them fail. Responding to this, it’s explained that there’s a safety margin of exactly five missiles. This instantly led me to think, “How the *%@# do you know?” They keep acting like the only possible factor in all this is the size of the asteroid. But what about, I don’t know, its density? They couldn’t possibly know that, so how can they know exactly how many missiles it would take to obliterate it?

There’s more. In a gaff that would have been dumb back in the ’50s but is downright embarrassing for a film made in 1979, the missiles are shown to be firing their engines for the entire hours-long trip out to meet Orpheus. The ones that go awry are so indicated by having their engines sputter out, at which point the errant missiles mysteriously fall away. Yes, in space.

Then we get something even dumber, I guess to symbolize this wonderful international unity. Before reaching Orpheus, the missiles rendezvous and somehow contrive to rearrange themselves, exactly alternating the US and Russian missiles in three neat little rows. In each row, I mean, where the missiles are arrayed in Russian / US / Russian / US order. Man, that’s some pretty fancy guidance programming there.

“Ebony…and ivory…come together in perfect harmony…”

Again, they really seemed to have blown their wad on the missile models and effects. I mean, the climatic New York meteorite strike is pretty lame, the Hong Kong one is mostly impressive in terms of the crowds shots, and the avalanche scene was imported from another movie entirely—and a Roger Corman movie at that. So you can see why they spend so much time here watching Hercules’ missiles going off. It’s because that’s apparently about all they had any money for. I’m kinda having a hard time figuring out where all those millions went, unless the cast ate up a lot more of the budget than I thought.

So the missiles are off, and the splinter hits New York. Thus is our main cast imperiled, and you can guess exactly how worrying that is. Let’s just say I won’t need an emergency session with a manicurist to repair my painfully gnawed fingernails. They use the venerable “shake the camera” technique to indicate the splinter hitting, and then some mock debris is dropped from the roof and so forth.

One guy is trapped beneath his collapsed workstation, and eventually we learn that *gasp* Adlon was killed, and also that *double gasp* woman with boyfriend who gave Tatiana a scarf was too. These deaths, I can honestly say, are fully as emotionally devastating as they are shocking.

“How can this happen? How can something like this happen to a young woman with a boyfriend and so may scarves yet to give?!”

For what it’s worth, the collapsing set isn’t half bad. However, the assemblage of stock footage explosions and building demolitions used to represent the meteorite strike, images generally tinted red for EXTRA AWESOMENESS, seems more like something from a TV movie than a multimillion dollars theatrical film with a (sort of) high powered cast.

Speaking of TV movies, we now enter the obligatory post-catastrophe / survival section of the film. This involves the Bradley leading the survivors through a side tunnel to make their (kinda) perilous way to a subway station so that they can reach the surface and safety. In other words, it’s like a capsule version of The Poseidon Adventure, only one where nothing much happens.

More to the point, I’m sure many in 1979 recalled at this point a 1972 TV movie called Short Walk to Daylight.* Starring James Brolin, it revolved around a group of passengers in a New York subway train who find themselves similarly trapped following an earthquake. Hell, it reminded me of that movie even now, and I haven’t seen Short Walk to Daylight since it was telecast back when I was all of about ten years old.

[*Younger disaster movie buffs, on the other hand, might instead recall Sly Stallone’s similarly monikered Daylight (1996), which is practically an outright remake of that earlier film.]

As this all transpires, the occasionally cut back to the missiles as they continue on their way, and eventually as they finally reach their target. Not to completely blow it for you, but the missiles strike Orpheus, and following another round of fairly lame effects, manage to magically atomize the thing. That’s right, no pieces or anything. It’s just gone. And since there aren’t any more splinters, the whole asteroid threat is by the boards. But in case you were wondering, why yes, destroying a gigantic asteroid in deep space with dozens of nuclear missiles DOES involve the generation of monumental, lingering fireballs.

Meanwhile, the control room survivors, following some…well, you can’t really call them adventures or anything…make it to the subway station. However, the entrance is blocked by debris, and the walls are starting to crack under the weight of the river. Pop quiz: What looks scarier; numerous shots of a purportedly menacing rock supposedly tumbling through space, or shots of watery gook menacingly oozing from wall cracks? [Answer: Neither.]

In any case, liquidized mud eventually starts spraying in (looking, it has to be said, rather unfortunately like excrement), covering the cast as they fight—well, spar—for survival. I can only assume that the notoriously prickly Connery was less than cheerful during this part of the shoot, which presumably lasted a few days at least. As it is, his character’s heroics have him being doused with and wallowing waist deep through the stuff at some length. He cannot have been a happy camper.*

Connery’s disastrous audition tape to host Dirty Jobs quickly became a YouTube sensation.

[*On the other hand, the extras were going through the same thing, but for probably twenty-five bucks a day and a box lunch. And they probably didn’t retreat to a macked-out trailer between shots, or have a limo to drive them back to their four-star hotel at the end of the day.]

As the cast flounders in the increasingly flooded station, I naturally assumed—since this is, you know, a Disaster Movie—that someone marginally more significant than Adlon and Scarf Lady would ‘tragically’ die for our deeply effected emotional jollies. Oddly, though (and arguably ruinously, at least assuming any viewer still gave a rat’s ass at this point), both the obvious candidates, Sherwood and Dubov, mysteriously make it out alive. Actually, optimally both of them would have died, probably after one courageously went back to help the other and they both ended up crushed under a collapsing ceiling or something.

Apparently, though, somebody must have thought that would be too much of a downer or something.I can only compare it to Jaws 3-D, when to my vast frustration and derision an entire team of performing water skiers falls into the water right on top of the film’s monster shark, and yet not a single damn one of them gets eaten. Seriously, did the people who made this movie even bother watching any of the decade’s previous (and generally much more successful) disaster films? Because man, this makes no sense whatsoever.

Anyway, all these threads—Orpheus approaching Earth, the missiles approaching Orpheus, the stuff in the subway, Gen. Easton (assuming you remember him from the beginning of the film; it was his kid who died in the Mars probe) overseeing the missile flight down in Houston—are featured in back and forth fashion and take quite a while to wrap up. Eventually, though, as noted, Orpheus is eradicated and the control center team safely escapes from the subway station to find New York a largely ruined matte painting.

“…and the Yankees win the World Series! The Yankees win the World Series!”

“Uh-oh…”

After that, it’s just the goodbyes.Dubov and Tatiana board a plane to return to the Soviet Union, with the former getting as a souvenir a baseball bat signed by the Dodgers. Ha, it’s a call-back! As for Tatiana, she and Bradley kiss, and vague noises are made that indicate the filmmakers were hoping for a sequel. (!) However, since they generally don’t make follow-ups to notorious flops, mankind was spared another disaster, at least of the cinematic variety.

Uhm, yeah, about that…

We end with a text card that reads “In 1968, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a plan was designed to deal with the possibility of a giant meteor on a collision course with earth [sic].* This plan is named PROJECT ICARUS.” Maybe that was the film’s original title, but anyway, it seems rather late in the game to act like this film was rigorously based on real life stuff.

[*Apparently MIT doesn’t know what a ‘meteor’ is either.]

Moreover, the text card is also narrated, something that always confuses me.Why do both?If you’re afraid your audience can’t read, why even bother with the card?Just have the narration. It’s like (fittingly enough) Henry Fonda’s character in Once Upon a Time in the West responding to one overly-cautious individual: “How can you trust a man who wears both a belt and suspenders? The man can’t even trust his own pants.”

The Aftermath:

For the savvy film buff, oddly enough, it’s the appearance of Sean Connery’s name during Meteor‘s opening credits that suggests AIP was heading into trouble. The company had survived more than three decades in the business, a truly impressive feat for an independent focusing on cheapjack fare. As a production house, they themselves made a myriad of films that remain better known and loved today than the vast majority of big studio fare of the same vintage.And as a distributor, AIP brought over 500 films to big screens during the company’s decades-long reign.

However, for some reason, mini-studios and production houses always seem to hit a point where they decide to try to go big time. This decision invariably spells their doom. It later killed, for instance, ’80s mini-titan Cannon Films.Not content with making reliable money with Chuck Norris and Michael Dudikoff films, they started doing things like offering (then) superstar Sylvester Stallone a (then) historic $12 million to star in their arm wrestling epic Over the Top.

Trying to go ‘respectable’ also killed AIP. Sometimes such moves are forced by market circumstances, but often they’re driven by sheer ego. Given his bottom line-oriented history, one imagines that it wasn’t by choice that Arkoff rolled such dice.On the other hand, he was getting older. It may be that impending mortality, as it often does, drove him to seek legitimacy before he passed.

In any case, theatrical independents like AIP were dying out by the early ’80s.By the late ’60s and early ’70s, such firms were increasingly screwed by the fact that the major studios, desperate for profits and increasingly unfettered by rampant social changes from any expectations of respectability, started producing and/or distributing fare of a sort they had previously disdained. Probably the true death knell sounded when Paramount deigned to release Friday the 13th in 1980…and made a slew of money doing so.

At one time this sort of disreputable exploitation material was the province of smaller and equally disreputable production houses. Increasingly, however, such companies found themselves directly competing with studio films that marshaled bigger budgets and far greater production values .It’s possible that Arkoff simply saw the writing on the wall and simply decided to take a shot. Arkoff’s long-time partner, James H. Nicholson, had passed away in 1972, and Arkoff himself was growing older. Indeed, after AIP was merged with Filmways in 1979, Arkoff retired. So it’s not like he really had that much to lose.

In any case, during his last days with AIP, Arkoff kicked off a move towards more mainstream fare. A few of these attempts were quite successful, such as the original The Amityville Horror and the Dracula comedy Love at First Bite. However, for every hit, there were half a dozen flops, such as Meteor.

Meteor rolled big dice for the company, as it was bankrolled to the tune of somewhere (depending on the source) between 16 and 20 million dollars. This was a pretty major budget at the time. Five years earlier, Irwin Allen’s star-studded epic The Towering Inferno, a Warner Bros./20th Century Fox co-production featuring a massive cast headlined by arguably Hollywood’s two biggest stars of the time, Paul Newman and Steve McQueen, cost $14,000,000. Meanwhile, 1974’s Earthquake, a film built around the very biggest effects the industry was then capable of producing, was budgeted at only $7,000,000.

Even adjusting for five years of inflation, Meteor‘s budget was obviously huge, and a commensurately huge gamble. It proved a bad one. The film gleaned only $8,400,000 at the domestic box office, and the rentals—the amount the studio actually gleaned from that amount—was a comparatively puny $4,200,000.It was a disaster movie, all right, but mostly for AIP itself.

Indeed, only the gigantic profits from the same year’s The Amityville Horror, made for a small fraction of Meteor‘s budget yet returning $35,000,000 in rentals to AIP, kept them briefly afloat. Even so, in the aftermath of Meteor, AIP posted that year its first loss in the company’s history.

The subject apparently remained touchy for Arkoff. In his entertaining memoir Flying Through Hollywood By the Seat of My Pants, Mr. Arkoff spends several pages on both Love at First Bite and The Amityville Horror. He also details at some length AIP’s merger with Filmways, and his subsequent resignation.

Arkoff wrote, “I believe that even though the film business became tougher and more hazardous for independents in the ’80s, AIP could have continued and done quite well. Ironically, my final American International “legacy” was three of our most successful pictures–not only The Amityville Horror, but also Love at First Bite and Dressed to Kill.”

Meteor isn’t mentioned in his book. Not once.

AIP staggered on a bit following this financial body blow, but the end was near. 1980 saw other attempts at bigger budgeted mainstream films such as G.O.R.P., How to Beat the High Co$t of Living and Nothing Personal.Denied success, AIP merged with Filmways and basically ceased to exist. Soon after that Filmways/AIP was itself folded into Orion. For himself, Arkoff left in 1982 to start Arkoff International Pictures, which never really got off the ground. Mr. Arkoff eventually passed away in 2001, a few weeks after the death of his wife, at the age of 82.

In retrospect Meteor‘s failure seems easy to predict. There’s a familiar toxic recipe for high-riding film genres (although these days it more applies to individual franchises). The formula involves budgets growing bigger in a seemingly direct inverse ratio to declining audience popularity. Toss in the fact that eventually the movies also start to suck, and—well, you don’t have to be that Little Man Tate kid to do the math.

So it was for Meteor.It wasn’t released in the glory days of The Poseidon Adventure, Airport, The Towering Inferno and Earthquake (two of which were nominated for Best Picture Oscars!). Instead, it came out when the once mighty Disaster Movie was all but dead, supplanted by sci-fi extravaganzas in the wake of Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Superman.

Even the disaster genre’s maestro, Irwin Allen, couldn’t keep it going.Both 1978’s The Swarm and 1980’s When Time Ran Out—a picture that reunited Allen’s Towering Inferno stars Paul Newman and William Holden—tanked just like Meteor.The fact is, the genre was just running out of steam. New fads were grabbing film audiences, and frankly, most of the good disasters had already been exploited. (Oddly, there was no theatrical film based on the Titanic during this period.)

I don’t know this for a fact, but it’s quite possible that the last guy to make a buck from the ’70s Disaster Movie might have been Arkoff’s old associate Roger Corman. As noted, his production company New World Pictures (sort of the Son of AIP) released Avalanche in 1978. I don’t know how much it pulled in, but I can guarantee one thing: Corman didn’t spend any 16 to 20 million dollars making it. Hell, I’m not sure it cost $1.6 million, given that Styrofoam ‘snow’ just doesn’t cost that much.

And, of course, Corman would have made extra money selling his old boss footage from the film for use in Meteor. I can only imagine how satisfying he found that.

Click on the above banner to go to the roundtable supersoaker!