First of all, let me admit that I’m just a little bit uneasy mocking this film. This isn’t, like many of our subjects, a no-budget botch job perpetrated by hacks. It’s not another limping reiteration of some genre that’s been flogged to death. Nor is it an elephantine ego project gone awry. It is, in fact, an earnest and well intentioned flick honestly trying to do some good. It’s just that it does it so…bad.

I particularly want to say that I’m in no way trying to make fun of David Wilkerson. Wilkerson was a minister from rural Pennsylvania who traveled to the ghettos of New York in (apparently) the ’60s. He ran a successful ministry there and managed to help some kids out of gangs, at no little risk to his own life. He wrote a book about his experiences, which was then adapted into our current subject.

The result is so stilted that one finds it difficult to believe that it was ever considered credible. Yet the video box quotes laudatory reviews from actually legitimate sources. The Boston Globe apparently found the film to be “[a]n artistic success.” As well, the Los Angeles Herald Examiner praised it as “[o]ne of the most entertaining films of the year.”

I agree, although I doubt that it entertained the reviewer for the same reasons that it entertained me. More amazingly, he judges that the movie “captures a sharp realism of the ghetto that can be recognized as true by anyone who has ever lived there.” Yet today even the most naïve viewer will laugh out loud at the film’s cornball depiction of life on ‘The Street’. Gritty it ain’t. Cross and the Switchblade ultimately makes our last ghetto epic, Change of Habit, look like Boyz N the Hood in comparison.

We open with your standard establishing shot of the Brooklyn Bridge. (We’re in New York. Get it?) This is accompanied by text informing us to prepare for “A Word from the Producer…” This proves to be your standard ‘our story might seem incredible, but nonetheless is based on actual events’ spiel. Yet even if we buy that these “events actually took place,” we can only conclude that much was lost in their translation to the screen.

We cut to a close-up of a switchblade being opened. This seems to me a rather cruel jest, raising as it does the hope that we will immediately cut to a cross and that then the film will be over. Instead, another close-up spotlights a teenaged boy’s face, his eyes popping wide with alarm. As some extremely ’70s wakka-chika music kicks in, he takes off through what we now see is a city park. A gang of toughs quickly takes up pursuit.

The reason the kid can run is that the film portrays an era where the gang weapons of choice were knives, chains and metal pipes. Ah, those innocent, halcyon days! Life was so much simpler then. Unfortunately, though, the lad proves insufficiently fleet. Pulled down from a fence, he is subjected to thugs savagely beating the grass around his head and torso. I guess that they have extremely poor depth perception. Either that, or they are actually supposed to be beating the guy and the action is just badly shot. Their task accomplished, the rowdies run off laughing.

They are met by a female accomplice on a nearby pathway. She opens a large purse, and they toss their implements of destruction inside. Just after the last punk drops something in the bag, though, a beat cop happens along. Emerging just then into the shot, the cop apparently doesn’t notice anything until the last guy stops to pick up something. Given the way the shot is filmed, though, there’s no way he could have not seen the entire loudly laughing gang throwing their weapons into the bag.

We cut to a trial. Already, the film’s age is limiting it’s impact. What, a specific guy beaten instead of being among those mowed down in a drive-by? And a lone cop happening on the scene apprehends the gang, rather than being himself shot down? And then the gang members are actually brought to trial? What next? Is the Sugar Plum Fairy going to make an appearance?

The segue from the park is accomplished by cutting to a photo-realistic charcoal drawing of the defendants. This, rather improbably, proves to be the work of a courtroom sketch artist, apparently the finest one who ever lived. Meanwhile, the actor playing the prosecutor chews out the line “What-did-you-do-after-he-fell-down?” in the manner of a recent immigrant phonetically reading from a translation guide.

After the defendant answers “I hit him,” the prosecutor similarly labors over the line “What-did-you-have-in-your-hand-when-you-hit-him?” Hmm. Actually, he might more sound like a movie robot than the aforementioned immigrant. Anyway, I’m busy wondering why this guy is on the stand. He can’t be propelled to testify against himself. Is he ratting on the rest of the gang? Then why doesn’t the prosecutor ask what they were carrying?

Right about here, the Subtlety Train completely leaves the station. In fact, the current sequence quickly becomes the silliest ‘trial scene’ yet to grace this website. Considering the fierce nature of the competition, in films ranging from Abe Lincoln – Freedom Fighter to The Sea Serpent to Body of Evidence, this is quite a distinction.

The prosecutor tries to get the mumbling witness to speak up. His lawyer objects, although he fails to state cause. (Presumably, badgering the witness). The prosecutor then whirls around and heatedly screams “Are you trying to make a fool of me??!!” (Not that he needs any help.) The screaming in open court seems a tad extreme, not to mention somewhat unprofessional. As well, the line makes little sense. How does a defense objection make the prosecutor look foolish?

“Your Honor,” he loudly continues, “I cannot complete my examination if this idiot goes on interrupting!!” Unsurprisingly, the defense counsel then objects to being called an idiot. The judge responds by reprimanding their remarks as discourteous to each other as well as to the Court. As the defense lawyer was only complaining about being called an idiot, however, I’m not sure why he’s also being chastised.

Now, though, it’s the defense’s turn to act like a loon. The prosecutor walks over and seizes the guy’s arm. Admittedly, such physical contact is way over the line, but the defense lawyer freaks out. “Your Honor, this man wants to assault me!!” He then demands police protection (!!) from the prosecutor. Man, and I thought the O.J. Simpson trial was unruly!

As the Judge attempts to reassert order, the most innocuous looking man imaginable enters the court. You might think I’m exaggerating, to which I reply with two words: Pat Boone. That’s right, Debbie’s dad. As if that’s not bad enough, Boone here looks almost exactly like Stephen Collins in The Promise. This is not a good start.

For some reason, the appearance of the extraordinarily whitebread Boone throws the court into a tizzy. He’s soon overwhelmed by guards and the Judge noisily orders him removed from the courtroom. Out in the hall, the cops frisk him, assuming that he’s connected with the gang (Pat Boone!) and carrying a gun. (To do what exactly?) Instead, all they find is a Bible. That’s right: Boone is our star, playing the real life David Wilkerson.

As the assembled press repeatedly takes his picture, the cops search his bible, thinking “Maybe there’s a gun in it!” We soon learn that Wilkerson’s parish has sent him to the Big Apple, hoping that he could help these troubled kids. At this, the Cynical Members of the Press have sport with him:

Wiseacre Reporter: “How do think that you can help those kids?”

Innocent Wilkerson: “I’ve got a whole church full of people praying for them back in Philipsburg, Pennsylvania!”

Unsurprisingly, at this the assembled reporters break into callous laughter. Oh, they of little faith!

The reporter tells him to pray for a miracle, as “the DA will burn those creeps!” Meanwhile, a cop informs Wilkerson that the Judge won’t press charges (for what?!) if he promises not to return. Shamefaced, Wilkerson agrees. Here the film counterintuitively proves the limits of prayer. For despite the fervid supplications of the audience, the words ‘The End’ fail to appear on the screen.

Instead, a photographer goads Wilkerson into holding up his Bible, at which he and his fellows snap his picture again. Meanwhile, a cop tells Wilkerson not to worry, as these kids “are not of your faith.” This is meant to reassure the audience that, like in the somewhat similar Change of Habit, religion will only be discussed in terms of its Social Relevance. Don’t worry, folks, none of that grubby ‘doctrine’ stuff here, by golly!

As Our Hero makes his leave, an elevator opens and disgorges a daisy chain of handcuffed young prisoners. A soulful tune appears on the soundtrack. “What can you dooo? / What can you say? / Where do you start…to begin…beginning?” warbles out as the camera zooms in on the suspiciously clean cut bunch. See, the lyrics tie into the action on the screen. Neat. The songs continues as we segue to the sun rising over the city. “You’ve got to realize / that you’re just one guy. / But on the other hand / the fact is, you’ve gotta try…”

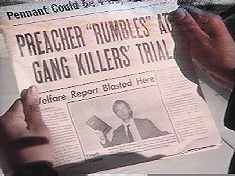

We cut to the front page of a local paper. Somehow, I suspect it’s not The Times. There we see the picture of Wilkerson with his Bible, adorning the front page (!). It’s nestled under a enormous headline that screams PREACHER “RUMBLES” AT GANG KILLERS’ TRIAL. (Shouldn’t that be “Killer Gang’s”?) As an added hint to the filmmakers’ commitment to Social Relevance, another smaller headline reads ‘Welfare Report Blasted Here’. I’m not sure what that means, exactly, but it does sound Socially Relevant.

We cut to a pristine classic ’50s Buick, the windows of which are covered up with newspapers. Inside we see Wilkerson sleeping. If one were to actually sleep in the position shown here, he’d wake up with neck cramps like you wouldn’t believe. When we cut outside, we see that the car is parked on a ghetto street, carefully festooned with trash for that Inner City look. A group of pre-teen kids appears, artfully begrimed and notably interracial in membership. They look like they just walked out of a Little Rascals short.

Here, however, the film shows us the gritty side of The Street. For the youngsters immediately start stripping Wilkerson’s car of hubcaps. (They waited until daylight for this?) Meanwhile, a slightly older Black kid peeks inside the car. He quickly reports to his older sister (I presume) that there’s a guy inside. The sister asks if the guy “looks bad,” i.e., tough (remember, we’re talking Pat Boone, here). Although nervous, the lad agrees to her plan: He’s to hold Wilkerson at bay with a switchblade. Meanwhile, she’ll grab his wallet.

So the guy waits for the noise of the kids ransacking his car to bring Wilkerson out. (Conveniently, despite the fact that each individual hubcap appears to pop off in a half second, the young hoodlums are still at it.) His sister positions herself on the opposite side of the car (?). Sure enough, Wilkerson soon makes an appearance, clad in evident flood pants that spotlight his bright red socks. You know, I can almost believe that he would go to sleep wearing his tie. But with his shoes and socks still on?

Our Hero proves surprisingly adept and soon has the kid in an arm lock. Proving that he’s perhaps not cut out for this work, the pinioned kid at this point yells, “Gimme your wallet!” Apparently noticing that things aren’t going his way, he then blurts out “Watch it, he’s fast!” His sister, meanwhile, worriedly watches. “Hey, Bottlecap, cool it!” she yells. “Let go of that cat!” (Bottlecap?! What it this, a Fat Albert episode?) As Bottlecap is the one being held, though, this advice proves less than pertinent.

Wilkerson manages to disarm his attacker and kick the knife away. Meanwhile, the sister runs over and immediately recognizes Wilkerson from his picture in the paper. Apparently, she’s a faithful follower of the Fourth Estate. “You the cat from the trial, ain’t ya?” she inquires. Wilkerson agrees. For some reason, this proves his ‘credentials’ to her. (Why? All he did was show up and immediately get run out of the courtroom.)

“Lay it on me, Baby,” she replies, putting out her hand. With this, she officially welcomes Jabootu’s third White Male Benefactor of the Minority Underclasses. (Notice that I’m not even counting the white scientists helping out the backward natives of Jungle Hell and From Hell It Came.)

Wilkerson, rube that he is (*giggle*), fails to recognize the universal hand gesture for requesting a High Five. Instead, he (*guffaw*) tries to shake her hand. “Don’t wrestle with me!” she reprimands. “Just lay it in the sky!” She informs Bottlecap how Wilkerson is “the cat who went after the Judge in the Egyptian King trial!” (Uh, sorta.)

The young lady identifies herself (really, I swear) as “Little Bo Peep,” but notes that Wilkerson can call her Bo. Her function, we quickly deduce, will be to act as Virgil to Wilkerson’s Dante as he tours this urban hell. Now that’s he cool and everything, Bo calls to the lads running off with parts of Wilkerson’s car, including the hood. She apparently has a fair amount of power here, as everything’s quickly returned.

As they reassemble the car, Bottlecap sits nearby, discoursing on how fine Wilkerson shoes are. His own tattered pair, we learn, were stolen from a wino. One, he suspects, with a fungal problem, since they make his feet itch. If you guessed that Wilkerson will soon, to the kid’s surprise, give Bottlecap his shoes, score yourself a point. If you also guessed that this will set up an improbable bit where the shoeless Wilkerson tours the dark areas of the city wearing only his socks (I mean on his feet, you perverts), well, I’d say you’ve seen too many of these movies.

Wilkerson learns that the Egyptian Kings aren’t even a particularly tough gang. The two “heaviest” are the Mau Maus (!) and the Bishops. Bo, we learn, has somehow maintained status as an independent contractor. She has no need, we learn, for “jitterbugging, and getting messed up, and cutting cats.”

Of course, she did set the knife-wielding Bottlecap onto Wilkerson. Apparently, she means cutting cats merely for fun, rather than for profit. Also, I don’t know what ‘jitterbugging’ means here, but it’s an unfortunately goofy piece of slang. It’ll be used throughout the movie, always in a serious context, and always inspiring a chuckle from the viewer.

Wilkerson asks if Bo believes in God. Bo replies that she’s more concerned with “pigs, and getting bread.” Bottlecap, meanwhile, still infatuated with Wilkerson’s footwear, notes that it’s “Easy for you to talk about God, a rich man like you, with that bad [i.e., nice] car, and those fine shoes.” At this, Wilkerson hands the shoes over, although not, I notice, his car. Wilkerson tells the hesitant Bottlecap to go on and take them. He has another pair, he explains, back home in Philipsburg. Yeah, that’s handy.

Impressed with his generosity, Bo offers to take him to see the Mau Maus, who are “some real boppers!” She warns him, “Don’t go laying none of that God stuff on ’em, though. ‘Cause they’ll cut you so full of holes that you can sprinkle the grass in Whatsamacallit, Pennsylvania, just by drinking a glass of water!” (Apparently, Bo has gotten her knowledge of human anatomy from watching Three Stooges shorts.) Here, Wilkerson proves a fast study, for when Bo holds out her hand again, he quickly slaps it five.

We cut to Wilkerson’s Chevy, missing a hubcap and with the hood tied down on the roof of the car (presumably for ‘comic’ effect), cruising down the mean streets of the city. Music that sounds like an incompetent imitation of Nelson Riddle’s orchestrations from the old Batman TV series accompanies this.

“This turf,” Bo explains as they drive along, “belongs to the AAAGP.” (American Association for the Advancement of Gangsters and Pot. This revelation is accompanied by ‘comedy music,’ to help us get how funny it is.) “They don’t rumble,” she continues, “they just freak out.” Much like the VWPGCWM, or Viewers Who Paid Good Cash to Watch this Movie.

Bo has Wilkerson pull over. “This is about as close as you’re going to get and still keep your car.” (Luckily there’s a conveniently huge parking space ready for Wilkerson’s gigantic vehicle.) They’re soon crossing the street. Nearby, in one of the film’s more symbolic moments, we see a garbage truck making a pickup. I half expected to cut to a frightened Roy Scheider, exclaiming that “We’re going to need a bigger truck!”

Bo and the still shoeless Wilkerson (couldn’t they have stopped and gotten some shoes before this?) enter an alleyway. Hewing close to the wall, they then jump up onto a small ledge to make their way. However, once they arrive at the end and jump down, a wider shot shows the alley to be entirely clear. This makes the whole ‘ledge walking’ thing seem a bit odd.

As they continue, Wilkerson is almost tragically hit by a falling water balloon. “Water,” he sagely notes. “If we’re lucky!” comes Bo’s reply. (?) Finally coming to their destination, Bo calls out to the gang’s lookout, Angela. Angela proves to be a hilariously clean cut young lady in a nice clean turtleneck sweater and slacks and fashionable haircut. Apparently, life on The Street takes a lot out of you.

Angela (licking her lips as a signal that her morals are less than they should be) thinks she recognizes Wilkerson. Bo replies that “you just seen his picture in the paper.” Which confirms that gangbangers and tough ghetto youths all start the day perusing their newspaper, presumably over a cup of joe and a fresh croissant. Seeing his shoeless condition, Angela laughs derisively. “Leave him alone,” Bo protests. “That’s his thing.” What, walking around in his stocking feet? Maybe she was laughing at his red socks.

Bo can’t take Wilkerson inside, as she’s not affiliated with the gang. So she asks Angela if she’ll take him in. Angela demurs. It’s a bad time, as the Mau Maus are expecting the Bishops to drop by for a “war council.” Bo presses, but Angela continues to resist, noting that that she doesn’t want to get “bawled out.” (The savage world of the gangs, eh.)

It turns out (duh) that Angela is looking for a fee for her assistance. She boldly asks for five dollars, to Wilkerson’s apparent shock. Bo pulls him aside for a conference. “Five dollars is this chick’s top price,” she explains. “For that you get two joints of marijuana, her body, and two bits change.” Apparently five dollars went a lot farther then. Bo suggests that three dollars should do. Hmm, considering what you get for five bucks, for three I’d at least bargain for a beer and a, uh, close personal favor of the type that President Clinton is so fond of.

Bo takes the money to Angela, but only gives her two bucks, stealthily keeping a dollar for herself. (What a scamp!) Angela pockets the money and escorts him in, through a door marked “Pigs and creeps, keep out.” Bo, meanwhile, takes off to “steal some breakfast.” That’s what she says anyway. Perhaps she just doesn’t want to get Wilkerson’s blood sprayed all over her clothes when they cut the interloper into tiny pieces.

Inside the main den, we meet Rosa, a young white woman who’s rather obviously (and I mean obviously) high. The film now takes another large step away from reality, the presentation of the drug scene here being slightly less credible than those ‘hippie’ episodes of Dragnet. Other youths are sitting around drinking, making out and getting high. Wilkerson is intercepted by stoner dude Chance, who looks quite a bit like a young Howard Stern. (Which explains a lot, actually.) “Hey, man,” he exclaims, fingering Wilkerson’s tie, “the tennis club is down the block!”

Once again, though, Wilkerson’s extremely short-lived appearance at the trial buys him some space. “That’s cool,” Chance posits, apparently more stoned than I thought. “Cool, man. Smoke my peace pipe.” Here he offers Wilkerson a hit off his wacky tabacky, which is obviously declined. Angela, though, isn’t as picky, and grabs off a large toke.

Immediately from off camera Angela’s brother comes into the shot. He grabs her and tries to shake some sense into her. Apparently, he doesn’t approve of her wanting to be a Deb, i.e., a gang party girl. He forces her to look at a couple making out on a couch, as an ominous blare of music issues forth. Next we see a guy snuggling with a girl and drinking from a liquor bottle. “Look at them!” he shrieks. “Do you want to be like them?!” I guess she doesn’t. Otherwise she’d have gone to college.

When he opens the door to boot her out, two Black dudes are revealed. One is Big Cat, wearing smoked glasses and carrying a stylish walking stick. Watching the film, it took me and a fellow veteran Jabootu enthusiast a good half hour to finally decide that Big Cat wasn’t meant to be blind. Whether the film’s that unclear, or whether it’s just that one’s brain stops functioning in an optimal fashion when watching this stuff, I couldn’t tell you.

“Tell the man we have arrived,” Big Cat orates in stentorian fashion to another ominous chord of music. “We are the chosen people! We are the Bishops!” With him is the Bishop’s “warlord” Abdullah, who comes complete with the obligatory dashiki. If I’m not mistaken, these are in fact the same two Radical Black Dudes from Change of Habit. If not, they’re close enough.

Chance points to an adjacent boiler room, and Big Cat leads his, uh, whatever they called a posse back in the ’70, inside. The Mau Maus are cinematically waiting in the shadows, so that they can emerge into the light in a ‘dramatic’ fashion. While the Bishops don’t have a gang outfit, the Mau Maus sport red jackets with two big ‘M’s on the back, matching fedoras with matches stuck in the headbands (?), and, like Big Cat, canes.

The leader of the Bishops announces himself in a manner certain to strike terror into the hearts of his enemies: “Big Cat’s the name, and jitterbugging’s my game.” At this, Israel, the “president” (?!) of the Mau Maus, steps dramatically into the light. (See, I told you.) The two gangs agree to meet Monday at the park (the “disputed turf,” we’re told) for a rumble. Big Cat suggests eight at night. However, one of Israel’s men points out that “we can’t see these cats at night!” Besides, nighttime means more police. Noon, when the neighborhood kids will be in school and not in the way, is chosen instead.

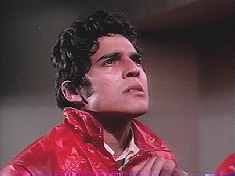

Unnoticed, Wilkerson enters the room. The gangs have now chosen the place and the time, and agreed to team up on the cops should they show up. Next on the agenda is to negotiate what weapons will be considered kosher. For this part of the powwow, Israel calls on Nicky, the warlord of the Mau Maus. To a burst of wakka-chika music, Nicky walks dramatically from the shadows. (You just can’t use an effect that cool too often.) This actually is a dramatic moment, however. For we can now see that Nicky is played by none other than a presumably very embarrassed young Eric Estrada.

“Zips, blades, straights, chains, clubs,” suggests Nicky. ‘Zips’ would be zip guns, the slang term for homemade firearms. These are generally crude one-shot devices consisting of a cartridge inserted in a pipe with some rudimentary firing mechanism. Straights, I assume, are razors. Mingo (who is, I gather, only a pawn in the Game of Life), a member of the Mau Maus, argues against the use of zips. Guns are more apt to draw the attention of the cops. So only the hand-to-hand weapons are agreed to.

At this point, Wilkerson decides to intercede. However, this poor rural Minister proves sadly unprepared for the scathing wit of the inner city gang member:

Wilkerson: “Can I say something?”

Big Cat: “I don’t know, Dude. Can you?”

Anyway, Wilkerson goes into that “there’s Somebody who loves you” kind of thing. (I’m more of a fire & brimstone man myself.) Apparently we’re to believe that gang membership is the result of feeling unloved. Therefore, if Wilkerson can only convince them that Jesus loves them, then his battle will be won.

Wilkerson soldiers on in the face of their withering scorn. When he asserts that the Lord loves them despite knowing of their “drinking, the marijuana…”, one of the Mau Maus satirically (or something) breaks out into a rendition of “La Cucaracha.” (?) I’m not sure why, but this is apparently humorous, since all the youths start chortling.

You know Wilkerson’s in trouble when he starts making arguments like the following: “You guys talk about getting high. Well, God will get you high!” At this point, the dashiki-clad warrior Abdullah asks, “What God you talking about?” Hmm. Dashiki. ‘Abdullah.’ I’m no expert, but isn’t this cat, er, guy (oops, now I’m doing it!) quite possibly a Muslim?

This rather nonsensical exchange continues. When asked if God “rumbles,” Wilkerson replies yes. (See, if you’re going to talk, I mean, rap with the kids, you’ve got to speak their language. Understand? I mean, dig?) “He’s fighting for you right now!”

Finally, in a display of détente, Wilkerson addresses the leader of the Bishops. “Big Cat? Mr. President? I’d like to shake your hand.” Big Cat, impressed with this display of courage (or something), indeed proffers his hand. Only, being black and all, he holds it out for a groovy ‘slap five,’ rather than a nerdy handshake. Wilkerson, remembering his lesson from Bo, lays some skin on him.

Then he turns to the Mau Maus. “Nicky? Mr. Warlord?” (Shouldn’t he address the President of the Mau Maus? Wouldn’t Big Cat take this as an insult, i.e., as suggesting that the Warlord of the Mau Maus possesses the same stature as the President of the Bishops?) Nicky is the film’s hard case, though. So when he offers Wilkerson his hand, it’s across his face. Hmm, maybe Eric Estrada should have become a film critic rather than an actor. Anyway, that answers that old question about what one hand clapping sounds like. (OK, I stole that joke from an old Rockford Files episode.)

Wilkerson turns his other cheek, so to speak. Unfortuately, it’s too late. The gangs have started mouthing off to one another again. Big Cat theorizes that the Mau Maus have produced Wilkerson in an attempt to change their minds about the gang fight. Israel replies that “The only thing we’re going to change is your lip. We’re going to push it up into your nose!” (That’s telling ‘im!) Big Cat responds in rhyme, as is his propensity. “When all your worst plan are made/You’d best sign up for Medicaid!” I don’t know who the guy playing Big Cat is, but apparently he only got the part because Nipsy Russell was busy.

Israel proves just as handy with a rejoinder, however. “You’d better forget about Medicaid, and start saving for your tomb!” (That’s telling ‘im!) A shocked Wilkerson, meanwhile, slinks out in defeat. He looks pretty bummed, apparently by the fact that it will take more than three or four minutes of uninspired preaching to turn these youths around. I guess that he’s not aware that hardcore gang-bangers often require a half hour or more of generic religious lecturing before reforming.

As he tramps dejectedly to the door, he’s intercepted by Rosa, the junkie. “Is He on my side, too?” she slurringly inquires. Then she laughs. “What’s He goin’ to do for me? I’m a mainliner!” To back up this assertion, she presents her arm. And while she has what seems to be a rather small number of needle marks, about three I’d say, they are unusually large. Apparently she shoots up using one of those cloth cake-icing dispensers.

“Heroin!” she clarifies, in case anyone thought her merely a clumsy needlepointer. “A whole mountain of ‘Snow White’!” Announcing that heroin is heaven, she asks Wilkerson what he can provide that’s as good. Well, young lady, maybe you can reap some satisfaction from an Oscarâ„¢ for Best Supporting Actress in honor of your magnificent thesping in this scene! Bravo! Bravo!!

Now we are treated to a unique artistic gambit, one designed to make the audience share Wilkerson’s depression. For he has no sooner stepped back into the alley than the film’s folk/pop songsters start in again. As if in answer to Angela’s questions, they croon: “Where is your good life? / Nobody kno-oohs / Doot doo doo doo doo / Doot doo dee doot doo doodly doo…” As my friend Andrew noted, it’s like they were just making lyrics up as they went along and then ran out of ideas. This certainly is as good a theory as any.

Unfortunately, though, they soon abandon scat singing and again try actual words. “You say that Love will change the world someday / How come it doesn’t happen right away? / Hey-hey-hey! / Where is the magic? / I’d like to see / Where is your good life? / Aren’t you coming on strong with me?” Certainly that last line resonates with the viewer, at least if they mean strong as in, “Man, that dude has some strong BO!”

Still, Wilkerson at least has some influence over Bo. She rejoins him and during their stroll lifts a trumpet left sitting in a front car seat. However, under Wilkerson’s expectant expression she puts it back. (You know, this is New York city. I mean, if you leave something valuable in your front car seat and then leave the windows rolled down, well, you pretty much deserve to be ripped off. Dig?)

Our duo heads back to Wilkerson’s car, with Our Hero still ‘comically’ shod only in his socks. Reaching his car, Wilkerson stops with an amazed expression on his face. He’s presumably agog at the freshly introduced horrendous continuity error. See, earlier we saw him park on the right side of the street, in front of a block of stores. We saw this clearly.

Now, however, we cut to what he’s supposedly looking at from the street. And not only is it from the perspective of someone parked on the left side of the street, but now instead of the stores we see a well-tended building with a great big cross on the roof. “Is that a church?!” he asks. Apparently the world of Master Detectives suffered a great loss when Wilkerson decided to become a minister.

Running from the right side of the street over to the, uh, right side of the street (my head hurts), Wilkerson and Bo approach the church. Singing is heard. As they enter the church and are seen, and the singing tapers off. Hector Gomez, the church’s pastor, approaches and instantly recognizes his guest. Man, they sure scrutinize their newspapers in this neighborhood! “We have all been praying for you,” he gushes to the flummoxed Wilkerson.

Hector introduces various members of the congregation, including his wife Raphiella and several cute kids. The ice broken, they swarm around their celebrity guest. However, a quick cut shows Bo nervously hanging out in the back. As a ‘street black,’ (I’m not sure how else to say it), she’s presumably unsure of the welcome she’ll receive from these clean-cut church goers.

She’s willing to speak up for Wilkerson, though, and calls out that he’s been sleeping in his car. Hector will have none of that, needless to say, and demands that he stay with him and Raphiella. Wilkerson gratefully agrees, especially as it will put him in proximity to a phone. See, his wife (we now learn) is expecting a baby. This is a plot device, by the way, that goes nowhere fast.

Hector is shocked to learn that Bo lives in The Street. Who ever heard of such a thing, especially in nice little town like New York? We learn that Bo chooses to live alfresco rather than remain in her family’s cramped apartment, shared by her ten (!) siblings. “So you will live with us, too!” the jolly Hector cries. At this rate, Hector will have more people living at his place than Bo does.

Suddenly the mood turns reverent. “What miracle,” Hector asks, “brings such a fine young man to our troubled streets?” Wilkerson replies that finding such wonderful supporters has renewed his faith in his mission here. At this, the exuberant Hector rushes forward and grasps his surprised guest in a bear hug. (Ah, those hot-blooded Latin types, eh?) Then, while still embracing Wilkerson, he holds out his hand for Bo to high five. I can dig it.

From this scene of Christian Fellowship, however, we ironically (*yawn*) cut to a close-up of a switchblade being opened. A pan back reveals a line of Mau Mau members, armed with knives, bats and machetes. Across from them are the Bishops, possessing similar accoutrements. They raise their hands in a Black Power salute. (I can dig it.) Oddly, everyone is attired in freshly laundered casual wear. Personally, I’d have worn my junky clothes. Maybe it’s Rumble Etiquette.

At a signal the opposing lines close together. Weapons flail, although none too effectively, it seems. A crane shot features the melee at a distance, with bad ’70s ‘action’ music accompanying the sortie. Close-ups then reveal the perhaps two dozen gang-bangers whacking away at one another. Then a practically indecipherable tune entitled “The Last Rumble” kicks in: “It’s the Last Rumble / Something, something / Whoa! / We gotta rumble, gettin’ it ooon!” Apparently, this tune is too much, for Israel now calls retreat.

The Mau Maus take off, the Bishops in pursuit. Meanwhile, a fairly small number of wounded remain behind. I mean, Israel and some others were wielding humongous machetes! We were shown prostrate guys getting worked over with baseball bats. Others had chains and knives. Frankly, it’s seems like there should have been a lot more casualties.

Israel’s retreat proves to be a clever trap, though. Compatriots of the Mau Maus lie in wait, ready to pull taut an ankle-high rope and trip the pursuing Bishops. The “Na Na Na” singing accompanying the scenes of running youths, though, tended to remind me more of a Banana Splits episode than anything else. I half expected a Mau Mau to yell out, “Uh, Oh, Chongo!”, followed by scenes of the Bishops being pelted with watermelons or custard pies.

Sure enough, though, the trap works. Although the Bishops are so spread out that no one other than the lead guy would have been tripped, they ludicrously continue to run into the rope like lemmings. Another undisciplined battle ensues (although by all rights the Mau Maus should have been able to work over their fallen foes at their leisure). Soon it’s the Bishops who are in retreat and the Mau Maus doing the chasing. The oddest thing is, although both fights left wounded on the ground, there seem to be ever more participants in the chase.

The Bishops run out of the park and into a nearby alleyway. Now we see their fallback plan. (Grant and Lee had nothing on these guys.) Running through a tunnel of boxes, they emerge in an enclosed courtyard. However, rope ladders are placed along one wall to allow them to escape. As the Mau Maus approach, a rope is pulled and the boxes forming the tunnel collapse, blocking them.

This gives the Bishops time to make their escape while the Mau Maus awkwardly push their way through the barricade. They then rather stupidly enter the enclosed area. This allows their opponents to pull up the ladders and then block the escape route with a well-tossed Molatov Cocktail. At this point the Bishops begin pelting them with bricks. (While this is pretty nasty, you have to wonder why they don’t toss a few more firebombs directly at them and burn them all like rats.)

Sirens are heard and the Bishops will soon have to flee. That’s OK, because their rain of bricks seems to be having a lot less effect than you’d think. We see some ripped shirts and stuff, but where are the concussions, the smashed out teeth and mangled eyeballs?

The cops, having made the scene, slowly approach the trash barricade. For some reason this is only partially aflame at this point. (Apparently, cardboard boxes burn in a very moderate fashion, especially after being sprayed with burning gasoline.) This allows the Mau Maus, lead by Nicky, to begin escaping up the fire escape. Meanwhile, they are still being pelted with bricks.

Then we cut back to the fire, which is now huge. (?!) Presumably, the cops are cut off, although they are nowhere to be seen, so it’s hard to tell. The Mau Maus, meanwhile, are jumping from one connected rooftop to another, making their escape. They are soon confronted, however, by a squad of cops equipped with riot helmets and billy clubs. Oh, and I just noticed that some of the Bishops, including Big Cat, are also on the scene. I have no idea how they got there.

The assembled members of both gangs run down yet another fire escape. Somehow they are now on the other side of the courtyard, up where the Bishops were when pelting bricks down on the Mau Maus. How the heck did they end up over there?! Then they all start leaping and running down a long series of stone steps, looking like nothing so much as members of a mass musical number from something like West Side Story.

Savvy Nicky grabs Israel and pulls him to safety moments before the cops cut off the toughs and apprehend them. They all give up after one officer raises his service revolver in the air and fires off a warning shot. Man, those were simpler times, weren’t they?

Nicky and Israel, now sporting much more stage blood than they were earlier, hustle to a rendezvous point. There they are met by Norma, a clean cut blonde in a sweater and skirt who looks like she just returned from Vasser. Laughably, she proves to be one of the gang’s ‘debs.’ She hands them their jackets, fedoras and canes, noting that only gang member Mingo has likewise made an appearance. Hearing Mingo’s name, Nicky grimaces angrily.

Israel orders Norma to stay there for another hour. Anyone showing up in that time is to receive their gear and be told where the official hideout is. Then he and Nicky run to the street and merge into the foot traffic. Oddly, their faces are now almost entirely clean. Israel pulls out a handkerchief to clean up, but why bother? The blood is apparently just evaporating off anyway.

We cut to a cop cutting through a crowd assembled on the street. The attraction proves to be Wilkerson. The cop, however, is unimpressed by his intention to preach. “We’ve got enough trouble,” he notes. Then he turns and begins to disperse the crowd. Now we learn a rather arcane point of law. I thought that they were joking at first, but apparently this used to be the law.

Wilkerson: “Officer, don’t I have a constitutional right to speak on any street corner in America?”

Cop: “Only under an American flag!”

Therefore, since the corner that Wilkerson is standing on lacks a displayed flag, he has no right to speak. This plot point established, the cop turns back around and resumes chasing off the spectators. Wilkerson, however, is not so easily put off. “Does anyone have an American flag?” he inquires. The cop threatens to run him in if he doesn’t take off.

The day is saved, though, by none other than Big Cat. Presumably to razz the cop, Big Cat snatches a little flag being used to decorate a car antenna. (Gee, that was handy.) Then he runs forth, looking oddly like an Olympic runner carrying a torch, and hands the emblem to Wilkerson. He posts it on a nearby fence but the cop remains unconvinced.

Apparently, he feels that the flag doesn’t count due to its small size. He declares it to be an insufficient “toy flag,” which is certainly a novel theory. Just then, luckily, the trench coated Lt. Columbo, er, Sergeant Delano happens by. (A lot of people just ‘happen by’ in this picture.) To the beat cop’s annoyance, Delano doesn’t share his views on the size restrictions of flags. So Wilkerson is finally allowed to speak. The crowd cheers, although that might only be because they haven’t heard Wilkerson preach yet.

Our Hero must first win over this cynical bunch of New Yorkers. “I’ve got a message for you,” he begins. A heckler responds by saying “I’ve got a message for you,” and giving Wilkerson a Bronx Cheer (i.e., a raspberry). The crowd roars with loud approval at this sly japery. Wilkerson, though, soldiers on.

“Is there anything in your life you’d like changed?” he asks. However, his quipping opponent isn’t through dispensing droll witticisms. “Yeah!” he yells. “I’d like to make the rich poor and me rich!” (To which hardcore Marxists in the crowd are presumably thinking, ‘You had me, then you lost me.’) Big Cat gets in on the hilarity with one of his impromptu verses: “We’ve got no love. We’ve got no bread. We tried to call the law, but the line was dead.” More mass laughter ensues. Apparently nothing goes over with New Yorkers like a non sequitur.

At this point, Nicky and Israel just happen by. (See what I mean?) Israel now has some of the blood he wiped off back on his face. I wish he’d make his mind up. Seeing the unescorted Big Cat (and why is he alone, anyway?), they move in to take advantage of their vulnerable enemy. Israel, however, stops when he spots the cop, still standing nearby.

Having endured the crowd’s taunting, Wilkerson fights fire with (*yawn*) fire. “Some of you are so blind,” he asserts, “you’re heading for a ditch and you don’t even see it!” (David Wilkerson – Master of Metaphor!) He warns them that they’re living in dangerous times. “The Bible says,” he continues, “‘How can you escape, if you neglect your soul?’ Now that’s one thing you can’t run away from!” Uh, well said. I guess. Wait, could you run that by me one more time?

Israel is shown listening with rapt attention, while Nicky urges that they leave. (Because Wilkerson is starting to get through to him, and he’s fighting it. Get it?) It’s a good thing they didn’t leave, though, because Wilkerson now unleashes his best line. “I see the hate sticking out of your eyes, some of ya.” Uh, well said.

Israel, meanwhile, shrugs off Nicky’s efforts to get him to leave. He looks especially struck when Wilkerson tells his audience that “You pretend that you don’t want anybody to touch you. But inside, you’re crying out for Love!” (The Gospel according to Leo Bascaglia.) Wilkerson then, in a bravado display, dares the “tough guys” in the crowd to “shake hands with a skinny preacher!”

He walks over to the leader of the Bishops. “Will you, Big Cat?” he asks. Big Cat pauses dramatically (well, not really, but you know…), then peels off his glove and takes Wilkerson’s hand. “What do you want me to do, man?” he inquires. “Pray with me!” comes the reply. I will give the movie this much credit: They don’t insert ‘Heavenly ah-ah’ music here. Big Cat, however, isn’t ready to make the leap yet. Seeing Wilkerson’s disappointment, he offers him some hope. “Don’t worry, though. You’re coming through.”

Wilkerson moves on, heading over to Israel and Nicky. Israel accepts his hand, to Nicky’s evident dismay. When Nicky is offered a shake, though, he spits on the ground. The crowd gasps and moans at this rude display with rather exaggerated horror. Wilkerson, although aghast, responds that “God loves you, Nicky.” “You come near me, I’ll kill you!” Nicky loudly replies. This, by the way, receives no reaction from the crowd. So remember this Etiquette Tip if you ever travel to New York: Spitting’s a no-no, but Death Threats are OK.

Wilkerson remains uncowed. “Yeah,” he responds, “you could do that. You could cut me up into a thousand pieces and lay me in the street. And every piece will still love you!” Sort of like the Sorcerer’s Apprentice scene from Fantasia, I guess, only with a twist. Nicky, apparently as freaked out by that little speech as I was (really, just read that bit aloud and see how it sounds), makes a quick exit. Delano, meanwhile, comes over and formally introduces himself to Wilkerson.

We cut back to the hideout of the Mau Maus. Horribly wounded gang members (where did these guys come from?) sit in chairs along the wall. Sporting their horrible wounds, including grievous burns (although we clearly saw no one get sprayed with the Molatov Cocktails), they rather amusingly recall the dead sitting in the afterlife waiting room in Beetlejuice. This impression is reinforced by a Halloween paper skeleton adorning the wall. (!)

As debs tend to their suddenly apparent wounds, an unscathed Mingo is bragging about his feats of valor. Nicky, entering from the hallway, is first seen appearing in a mirror behind Mingo’s back. (They must have a class called ‘The Artistic Uses of Mirrors – 101’ in film school.) A disgusted Nicky accuses Mingo of running out on the fight. “You calling me a liar?” Mingo bleats. “I’m calling you a liar and a chicken!” Nicky angrily retorts.

Nicky shepherds the walking wounded into a line. They all remove their belts, buckle-end up, and create a gauntlet. Nicky orders Mingo to enter it. Just then, however, Israel shows up. Feeling that Nicky has overstepped his authority, the irate Israel pulls him into a corner. Nicky, however, chides him for hanging out (*gasp*) with Wilkerson. “He’s just a nice guy with a lot of guts trying to help people,” Israel responds. (This guy is a gang leader?)

Nicky here points out the obvious: “He wants to break up the gangs! What the hell do you think he’s in the neighborhood for?” Yeah, you’d think Israel would, in fact, also have a problem with that. This, by the way, is Estrada’s big Oscarâ„¢ Clip moment. He wails and cries and slaps the walls. (You wouldn’t want him to mess up his hands by hitting a brick wall with his fists, would you?) I guess it would be mean to make fun of his acting here. Still, you do wish he’d light some of those matches stuck in his hatband and clear the air a little, if you know what I mean.

Nicky, apparently, can’t handle the pressure of Wilkerson’s attention. “Why does he have to pick on me?” he shrieks. “Because you’re the worst, craziest bastard there is,” Israel sagely responds. “If he could reach you, he could reach anybody.” Actually, I really wouldn’t mind living in a universe where Nicky represented the absolute worst that mankind had to offer. Sounds pretty peaceful, actually.

That fit of histrionics out of the way (Acting!), Israel removes his own belt. At the sight of this, Mingo takes off, the rest of the gang in pursuit. Discordant trumpet cords bleat to reflect the ominous actions on the screen. Out in the alley, Mingo clambers onto a nearby fire escape. The gang quickly emulates him.

Then comes a rather glaring continuity error, as Nicky engages in an act of Offscreen Teleportationâ„¢. One second, a wide shot clearly reveals Mingo to be at least a floor higher than his pursuers. This includes Nicky, who is quite distinctly in the shot to his rear. The next second, a close-up shot reveals that Nicky has not only somehow caught up with Mingo, but has actually somehow gotten in front of him and is blocking his way. (?!) Mingo, spaz that he is, backs away and manages to fall off the fire escape. This, as you might expect, results in a compromise of his body’s structural integrity.

Angela, the girl who wanted to be a deb (remember?), shrieks with horror and runs to Mingo. From this and an earlier reaction shot, I guess, possibly, that we’re to deduce that she had something going on with Mingo. Or maybe not. If so, it’s otherwise ignored and goes nowhere, so who cares.?

Then, for an ironic punctuation to the scene, Norma runs up. “Who won?” she asks, referring to the gang fight. “Who gets the park?” “I don’t know.” Israel realizes with shock. Wow, so it was all for nothing. The fighting, the blood, the seared and flayed flesh and broken bones, Mingo, everything, and nothing was even resolved. It really makes you think, doesn’t i…hey, wake up! You heard me!! Wake up, over there!!

We cut to Nicky in his (I must admit) authentically tiny and hovel-like apartment. He’s tossing and turning in his sleep, perhaps dreaming of the critical response to his performance in this film. In case we don’t get it, we see into Nicky’s dreams and see Mingo again falling from the fire escape. In a truly extraordinary coincidence, Nicky sees this, not from his perspective on the fire escape, but from the exact angle that the camera showed it to us earlier. He evens sees himself and the gang looking at Mingo on the ground, again from the same angle that the camera portrayed it. What are the odds, huh?

Then he starts dreaming of Wilkerson, again seeing himself spit at him and slapping him in the face. He’s then awakened by a knock at the door. (“Movie Police! Open up, we’ve got the place surrounded!”) Grabbing his cane and raising it, he opens the door and finds…Wilkerson. He again tosses the ‘God loves you’ thing at Nicky, who responds (not entirely without cause) “You woke me up to tell me that?!”

When Nicky again threatens to kill him, Wilkerson answers that “I’m not afraid of you.” “You talk tough,” he continues, “but inside you’re like all the rest of us. You’re scared.” (Apparently there are no sociopaths in the this universe. Again – nice place.) It’s when Wilkerson asks the searing question, “Aren’t you lonely, Nick?”, though, that he finally provokes a response. “Damn youuuu!!” Nicky caterwauls, slamming the door.

The next day, Rosa the junkie (remember?) enters a neighborhood candy store. This kicks off another couplet by our narrative minstrels. “Love is only a word to me / A word you use when you’re not too sure of what…to say…” Here, luckily, they’re cut off before they can go into that “doot doo doodly doo” stuff.

Nicky, once Rosa’s lover, is already inside, enjoying a tasty ice cream treat. She plays up to him, trying to cadge ten bucks for a fix. Nicky, however, contemptuous of her weakness, wants nothing to do with her. “Trust me, Nicky, just until tomorrow.” “I wouldn’t trust you to yesterday!” he snarls. (?) Hoping to soften him up, she speaks of her feelings for him. “I know a deb is supposed to belong to the whole gang [boy, there’s a career option for you!], but I only really ever belonged to you, Nicky!”

She reveals that she only enjoyed, uh, extra-curricular activities when with him. “I really dug it,” she asserts. “Write it in my yearbook!” he snaps, tossing her off. (At least that makes more sense than his ‘trust you to yesterday’ crack.) However, he realizes that he can use her desperation for a fix to his advantage.

He drags her into the store’s phone booth (Kids, ask your parents!) and closes the door. “What do you want me to do?” she whines. “I want you to get rid of the Preacher,” he replies, flipping open a switchblade. “How?” she asks. “Kill him, scare him, ball him [uh, does that last one really ‘get rid of him’?], I don’t care.” If she takes care of Wilkerson, he promises, he’ll take care of her. Lost in the power of the Horse with No Name, she can only agree to his terms.

Cut to an odd scene that really doesn’t have much to do with anything. Israel and two others run into a hallway with a sack of swag. From their comments we learn that they thought their victim was Jewish. However, upon examining their ill-gotten gains, Israel finds a crucifix. “The guy’s a Catholic!” one thug yells, while the other crosses himself.

His conscience bothering him, Thug #2 suggests taking the crucifix to the hospital and giving it to Mingo. Thug #1 laughs at this pious suggestion, noting that Mingo wouldn’t even know what it was. “That’s right,” replies Thug #2, “he’s still in a…ca…a coma?” As he stutters over his apparently exotic word, his buddy has sport with him. “A ‘kimono?” he laughs. “Mingo’s in a kimono!” So…ghetto thugs know what a ‘kimono’ is, but have trouble with ‘coma’?

Cut to dinner at Hector and Raphiella’s place behind the church. There Bo (looking much more clean cut), Wilkerson and Sgt. Delano are having dinner. Apparently, this in the days before Taco Bell, as both Bo and Wilkerson seem to find the basic Mexican fare quite a novelty. “Mmm, these are delicious,” Wilkerson notes, biting into a tostado. “We don’t have anything like this in Phillipsburg!” Boy, the Big City, huh?

Delano expresses his admiration for Wilkerson’s accomplishments. “You’ve been working with a bad bunch of apples, and you’ve got them smiling!” (Thus proving that as a wordsmith, he’s a good police officer.) Wilkerson, however, is depressed by his inability to reach Nicky. He also feels that the moment he approaches a breakthrough, the kids just tune him out. “Maybe if I could get them all together in one big place…” he muses. Yeah! And put on a show!! It always worked for Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland!

“You mean a rally!” Hector exclaims. “Yeah, a rally!” Wilkerson concurs. “All the beboopers and jitterbuggers and everybody!” Delano warns about how dangerous such an enterprise is (yeah, to the audience’s suspension of disbelief), but Wilkerson is too enthused to listen.

Wilkerson notes that they’ll need a place large enough for “every gang member and junkie in New York!” Bo smirks. “That don’t take a hall, it takes the Grand Canyon!” Actually, when the time comes, we’ll see that “every gang member and junkie in New York’ ends up being the Mau Maus and the Bishops. In other words, maybe two dozen people.

Cut to Israel and Nicky rapping at Gang HQ. Nicky again gets on Israel’s case about his chats with Wilkerson. They both pretend to find Wilkerson’s ministering to them comical. Yet, like gods we peer into their souls and perceive the spiritual voids that they are so desperate to fill. Or something.

Back at the Gomez’s, dinner is interrupted by the doorbell. Then the phone rings. It’s Gwen, Wilkerson’s pregnant wife. Out in the chapel, Hector opens to door to find Rosa waiting. (Remember? Her nefarious purpose?) Hector, proving to be somewhat naïve, asks the sweating, agitated Rosa “What’s the matter with you?” She demands to see Wilkerson.

Freaking out, she runs into the home quarters, searching for him. She comes to a halt, however, when she sees Delano, whose extremely evident gun identifies him as a cop. She then demands that Wilkerson, still on the phone, talk to her in private. The two of them head back into the chapel. She rambles incoherently (gee, who’da thought), then asks for ten bucks. He, of course, refuses, because of the whole “Man of God” thing. “You’re a filthy fink!” she replies.

Enraged, she pulls the knife, and after some travail, manages to open it. She swipes it at Wilkerson and manages to slash his shirt. The Gomezes and Delano appear, and Rosa takes off. Raphiella, however, manages to cut off her escape. Trapped, Rosa puts the knife at her own throat. This is meant to be dramatic, but since it recalls a similar scene involving Bart the Sheriff in Blazing Saddles, the effect is somewhat lessened. Having the audience impersonate Rosa saying in a deep voice, “Nobody more or the junkie gets it!” probably isn’t what the filmmakers had in mind here.

Rosa indeed threatens to kill herself. However, Raphiella talks to her and gets her to put down the knife. (Frankly, Raphiella seems a lot better at this sort of thing than Wilkerson. More believable, anyway.) The scene ends with the two women embracing. Awww!

We cut to the obligatory montage of Rosa suffering from heroin withdrawal. I think that you can pretty much envision what this is like. What you probably can’t predict, though, are the lyrics that accompany this bit. This section of our musical narration is somewhat weird, presumably to reflect the ‘heroin’ thing. “Cover my ground with fleecy white snow / Cover my floor with dust / Cover my walls with spidery webs / Cover my mind with drugs…” I think. And so on, until Rosa is, presumably, over the hump.

Cut to a funeral procession driving down a rainy street. This just happens to stop (a funeral procession?!) in front of a hall where a sign is being put up that reads “BIG YOUTH RALLY / DAVID WILKERSON”. Seeing this, Nicky snarls “I wish he was in that box instead of Mingo!” “Yeah,” Israel agrees, “poor Mingo.” This dialog cleverly helps us to figure out that this is Mingo’s funeral. Just in case, you know, we were wondering.

At the cemetery, we see a knife-wielding member of the Bishops. Strategically camouflaged in a bright yellow shirt and glaring red headband, he’s lurking behind a tombstone. Meanwhile, an utterly inappropriate blues harmonica wha-whas as we look over the group of mourners. Soon the extras leave, and only Israel, Nicky and a couple of others Mau Maus are left. (Apparently, appearance at a gang member’s funeral isn’t mandatory.)

Walking to the open grave, Israel tosses in Mingo’s gang jacket, fedora and cane. Then we see him fall into the grave. Music explodes (well, pops) as we see that the Mau Maus are under attack from a sizable group of Bishops. We clearly see Nicky and at least one other guy getting slashed with huge honking machetes.

Suddenly, cop whistles are heard (that’s convenient) and the Bishops run off. Laughably, we see that all of two cops are causing their retreat. The two other generic Mau Maus run off too, including the one we saw getting worked over with a machete. Next, Nicky staggers off. Again, while he’s obviously hurt, for a guy who’s just suffered from a machete attack, he looks pretty good. Finally, we see Israel pulling himself out from Mingo’s grave.

Having run all the way back to the city, Nicky collapses in an alleyway. Bo just happens to walk by (see previous note), and sees his (somewhat) bloodied condition. “Hey, Nicky,” she asks. “What’s the matter, you get hurt?” Seeing that this is so, she goes to get help, and in roughly ten seconds returns with Wilkerson and the cleaned up Rosa. I guess they were just happening to walk by.

Wilkerson begins yakking again at Nicky, who’s in too bad of a shape to do much about it. Seeking some respite, Nicky again staggers off. “He won’t listen to me,” Our Hero mutters. Given the circumstances, this makes him sound a trifle self-absorbed. Rosa, who has hopes of winning Nicky’s love now that she’s off the stuff, asks Wilkerson if she should go try to help him. Wilkerson sends her after him, which seems pretty stupid to me. “Tag along, Bo,” he orders, like he’s the leader of the A-Team or something.

As Nicky makes it to his apartment, Rosa dismisses Bo. Meanwhile, she yammers on to him about how she’s clean. The last thing Nicky wants to deal with right now, though, is one of Wilkerson’s rehab projects. He begins to berate her, in a scene where again we see Nicky via a mirror. Wow, that’s twice they’ve done that now. I guess that that officially makes it a ‘motif.’

To emphasize Rosa’s pain at Nicky’s rejection of her, that stupid “Cover my ground” heroin song starts up again. Sure enough, Rosa runs off to seek surcease of sorrow via her drug of choice. She runs past a tabby cat. Apparently afraid that we won’t recognize that it’s a cat, they dub in a loud ‘meow’ sound to clue us in.

Rosa enters the tenement where her pusher lives. Seeing a fellow junkie liquefying his drugs with a lighter, Rosa grabs his arm to request a taste. You’d think that an experienced junkie would know better, and sure enough, the guy ends up spilling it. Actually, he’s pretty polite for a junkie in this situation. He merely pushes her away, rather than freaking out and stabbing her a hundred and forty-seven times.

Rosa runs up the stairs to her pusher’s apartment. He’s glad to see her. Can’t have the customer base kicking the habit. He heads to his secret stash, which proves to be about two dozen little bags taped to the underside of his toilet seat lid. Presumably, they are located there so that he can send them on a quick waterslide trip should the cops show up. Or maybe it’s supposed to be symbolic.

Mr. Pusher is extremely helpful, even given her cash-free state. “First one is free,” he exclaims, the universal law of pushers everywhere. To make sure that she gets the full effect, he puts what seems to me to be a rather large amount of horse in the spoon. This is held over a hotplate and soon is ready to be injected. To be fair, they do manage to make all this look suitably gross and unsanitary, even for this pre-AIDS era. Of course, shooting up heroin isn’t an activity that requires tremendous skill to be made to look unpleasant.

Here comes the film’s most unrealistic moment, which is saying something. Rosa waits as he shoots a big wad of the stuff into her arm. Soon, though, she reacts angrily to the fact that it’s having no effect. She accuses him of stepping on it (Street Lingo Ken, they call’s me), a charge he denies. “It’s the best!” he maintains. Apparently, her body has so kicked the habit that heroin doesn’t even effect her anymore.

I know. I don’t think that that’s how it works either. Certainly, the pusher doesn’t think so. He reminds her that the second dose costs moolah. “And so does the third, and the fourth, and the four thousandth!” However, he also offers financial advice to his clients. For Rosa, he suggests a career as a sort of Street Entrepreneur. “And stay away from that preacher,” he exhorts. “Somebody’s messin’ with your head.” However, a shot of another zonked-out junkie is, I believe, supposed to make us question whether it’s not the pusher who’s messing with Rosa’s head. Get it?

Cut to the ‘Youth Rally.” Delano is setting up the stage, while Bo, Hector and Raphiella are laying out stacks of Bibles. The audience, though, currently consists of only a handful of squares (and hardly young ones, at that). Certainly not what Wilkerson had in mind. ‘Entertainment’ is being provided by a multi-ethnic folk trio playing guitar. Thankfully, though, it’s purely instrumental. I’ve think we’ve had all the ‘singing’ we can stand in this picture.

A pensive Wilkerson looks things over from the balcony. Seeing him, Delano walks up for a chat. They discuss the lack of gang member and junkie attendance. Here, Delano provides a look at the amazing deductive talents that make him a successful police sergeant. “Maybe I’m the reason they’re not coming,” he theorizes. You know, given how he’s a cop and all. He says that for tomorrow’s show he’ll stay away, and make sure that there are no cop cars parked nearby. Hmm, yes, that might help.

We cut to the Bishops and the Mau Maus having another council meeting. Nicky, apparently, is all fixed up from his slight concussion and machete wounds. The two gangs stand in semi-circular lines, opposite one another. When the leaders from each side move in to talk, the whole scene rather laughably resembles a marching band forming a heart shape.

The Mau Maus are rather pissed about the whole cemetery attack, which apparently violated ‘gang’ protocols or something. Israel demands another gang fight, and Big Cat is happy to oblige. When he suggests the park again, though, Nicky interrupts.

This fight is to be for all the local territory rights. Israel asks how they determine who’s the winner. “Last man standing,” is Nicky’s reply. Apparently, the gang who has a member still living at the end of the fight will get to control all the local turf. Whether this person will be able to keep control of it seems beyond the current scope of these talks.

Big Cat questions how this would work. “As soon as we get it on, everyone runs all over the city.” No problem. In order to keep people from taking off before matters are settled, Nicky suggests having the rumble in an enclosed area. Someplace where they’ve be trapped until everything’s decided. Then, unsurprisingly, he suggests the Youth Rally. Seal off the doors (how?) and get it on until things are taken care of, once and for all.

Abdullah expresses his approval of this plan. At this point, to the chagrin of Israel and Big Cat, the two warlords freeze them out and set things up themselves. In this manner, matters are quickly settled. Even zips will be allowed this time, as long as they aren’t “store bought stuff.” I guess that rules out Uzis.

Cut to the Rally. Wilkerson, not privy to the plans, is glad to see an actual gang turnout for tonight’s show. Again, I must mention that the rather small size of the two gangs (and aren’t there any other gangs in New York?) sort of mocks Wilkerson’s earlier fears about not having a large enough hall. Even with a couple of dozen solid citizens on hand, the place remains largely empty. Even more so, in fact, as some of the normal folks hightail it out of there once the gangs show up. (What were they doing there in the first place?)

Once seated on opposite sides of the hall, the two groups start to hurl ‘watermelon, watermelon’ sounds at one another. Mostly, they just snarl at one another, sounding like two arguing contingents of Frankenstein Monsters. They also start brandishing weapons, which you think would pretty much clear out the place. However, some hardy (and extremely moronic) people stick around anyway. And no, I’m referring to the people watching the film.

Backstage, Wilkerson looks to Heaven and prays for guidance. It’s a little late for that, though. He should have prayed for a better script before they started shooting the film. Out front, Hector is getting a bad vibe. Probably the result of, you know, the two gangs of hooligans yelling and waving weapons at one another. Wilkerson, however, has an idea. “We’ll let Mary sing. Maybe that’ll cool them down.”

Mary proves to be a rather sweet looking young lady, who now takes the stage. (Hey, remember to bring it back later! Ha! I’m so funny.) However, she doesn’t appear to be prepared for this particular crowd. Their whistling and catcalling quickly shake her up. I have to admit, though, that she sings well. Improbably well, actually, if you know what I mean.

The soppy lyrics of her tune leave something to be desired, though. “Someday, a bright new wave will break upon the shore / And there will be no sickness, no more crying, no more war / And little children never will grow hungry anymore / and if she keeps this up much longer, we all will start to snore…” OK, that last bit is mine. Hearing this slop, the gangs react like any sane person and soon have jeered Mary off the stage. Actually, she got off lightly. I mean, considering how her audience was packing heat and all.

Wilkerson at this point begins. He wants to collect an offering (?!), and picks four gang members, including Nicky and Abdullah, to collect it. Calling them up to the stage, he hands them empty cardboard milk cartons. Then he sends them forth into the audience. Actually, this is proves to be a smart business move. A glowering Abdullah, unsurprisingly, is shown to collect more money than Mary probably would of.

Wilkerson told them that when they were finished, they should walk around backstage and bring him the money. Once they are back there, though, and out of sight, they have a conference. Abdullah wonders if they should split the proceeds now, or let the winner of the rumble have the whole pot. Nicky, though, smells a rat. He thinks that Wilkerson thinks that they’ll take the money. Therefore, to cross him up, Nicky suggests actually turning the money in to Wilkerson.

It turns out, though, that Wilkerson isn’t surprised to get the money at all. See, while Nicky thought that Wilkerson would think that they’d keep the money, Wilkerson thought that Nicky would think that he would think…my brain hurts.

OK, now here is where critiquing the film gets a little delicate. I’m a Christian, and I certainly believe that coming to Christ can transform one’s life. And, to be fair, some of the final sermon here and Boone’s presentation of it are actually pretty good stuff. Yet, I have to say that, particularly to more cynical modern viewers (including myself), the success of this sermon seem a bit too abrupt.

The idea that the film’s been trying to establish is that Nicky is the hardest case of all. If Wilkerson can bring him to God, the rest will be unafraid to follow. And this apparently is what more or less happened in real life. After all, Wilkerson and Nicky, and presumably other characters in the film, represent real people. One wonders, however, if this mass conversion of everyone in both gangs (minus one) is really what happened. I’d think it more likely that Wilkerson’s success was somewhat less total, and that it probably took a bit longer than we see here.

Certainly, when Robert Duval in his extraordinary film The Apostle helps Billy Bob Thornton to accept Christ, it comes off as rather more authentic. There, Thornton was evidently a character in some spiritual pain. Here, that isn’t really established for anyone other than Nicky. All the other members of both gangs seem pretty happy with the status quo, and thus their conversions seem a little strange.

Wilkerson begins his sermon by decrying ‘labeling.’ “I bet you thought that asking those guys to collect money was like asking a junkie to guard a drugstore!” Cut to the Bishops, laughing en masse at this drollery and slapping each other five. Other than Abdullah, of course, who as the lone (?) Muslim in the group seems less than pleased with the effect that Wilkerson’s having on his cohorts.

Wilkerson avers how, by turning in the money, these fellows shook free of their labels. Still, this is only the opening gambit in a longer battle. Opposition comes in the form of cynical quips from the audience (I mean the one in the movie). “That’s because they’re suckers!” one wag shouts, to the general amusement of his fellows. (This is the kind of crowd that stand-up comics must dream about. A tough room it ain’t.)

No one can label you, Wilkerson continues, for no one really knows the real you. “No friend, no gang member, no deb or dittybopper or preacher or priest or rabbi or social worker or psychiatrist, nobody.” (Dittybopper?) “That why I don’t preach religion,” he continues, although why he’s waving that Bible around then, I don’t know. In so many words, he, like many others, is more interested in Christ’s utility in improving lives than in saving souls. I have some rather severe theological problems with this, but this is neither the time nor the place. Besides, it’s Wilkerson’s movie.

We now learn, I guess, what a ‘dittybop’ is. “I want every dittybop off!” Our Hero cries, and we cut to Mau Maus removing their fedoras. (?) So that mystery, at least, is solved. “I’m going to talk about Love,” he continues. “That’s right, Love! That word that bugs you. It’s a sissy word to most of you!” Wilkerson’s here to prove them wrong. “You’re going to see tonight that Love is the gutsiest word in the English language!”

From here his presentation gets somewhat better. Still, I could personally do without lines like “Jesus was a package of pure Love! Sweet, straight Love!” The problem I have is more the extremely subdued reactions shot of the suddenly cowed gang members. It just strains credulity that every single one of them (expect Abdullah) is so quietly enrapt by Wilkerson’s sermon. Perhaps if there were more Revival Meeting fervor in the audience, the sense of an almost palpable gestalt emotional wave, it would be more credible.

The speech also, sadly, plays an early version of the race card. Wilkerson asks the Mau Maus to “turn away from hating for your Black brothers!” However, he only exhorts the Bishops to “forgive the White Man’s sins!” In other words, when a White man (or Hispanic) is a gang member, it’s a conscious choice. A Black man, however, is only a gang member because he’s reacting to another’s hate. That this, like all such arguments, is inherently racist (as it assumes that Blacks don’t or can’t make moral choices for themselves) apparently has escaped the attention of the film’s producers.

Some of the gang members protest that the sins committed against them are too great to forgive. (Lexical note: Whites really do have an advantage in the war of Rhetoric. When one of the Mau Maus uses the ‘N’ word, it’s still shocking. In fact, perhaps it’s even more shocking now than it was then. However, when a Bishop attempts to insult in return with the term ‘honkies,’ it’s, as ever, rather comical.)

Wilkerson’s having none of this circular logic. “Everyone’s griping about this atrocity, and that tragedy!” I quote this line because it seems to me to be self contradictory. Is it even possible to ‘gripe’ about an ‘atrocity’?

He goes on to note how Jesus experienced the same pain and fears that any man would when he was crucified. Fair enough, but was it really necessary to note how nails were driven into “his hands! A sensitive part of his body!” What, exactly (and I really hope that this isn’t coming off as blasé towards what is the single most momentous moment in human history), would be a less ‘sensitive’ part of the body to have nails driven through?

One major problem with this film is its tendency to shoot itself into the foot whenever it approaches success. As Wilkerson preaches about how Jesus voluntarily died for our sins, the sermon picks up steam. Suddenly, Nicky’s crying reaction shots (an actually nice acting moment from Estrada) don’t seem so comical. Yet, they can’t seem to rely on the essential strength of this message, one that has changed the lives of millions upon millions of people over the last two thousand years.

Instead, they have Nicky look up, and then ruin the entire thing by insanely freeze framing Wilkerson. As his sermon continues to be heard, jingling, tinkling wind chime-like music is heard. Behind the frozen image of Wilkerson, the screen turns blue, and shafts of light appear in the background. Apparently, they didn’t want to indicate Nicky’s conversion with the traditional, cliché “Heavenly Ah-Ah” singing.

Here we observe a regular problem among the kind of movies we examine here. When they decide to avoid using clichés, they invariably end up substituting something so stupid that you realize why the clichés are used in the first place. A far wiser choice, if they didn’t want to use Ah-Ahing, would have been to just leave it alone. Let the sermon and Estrada’s acting carry the scene with a little dignity.

As well, that weird frozen shot of the grinning Wilkerson seems more like the idolization of a cult leader than the reaction of someone coming to Jesus. A preacher, after all, is only the messenger. It’s the Word that should be emphasized here, not Wilkerson.

And if you’re going to try to do that, as they belatedly do, it’s not really wise to use an echo chamber (!) to emphasize the final two words of the last line of the sermon: “Let Jesus Christ come in!” With those final words reverberating in our ears, we can only think of the aural shenanigans that William Shatner used to spice up his renditions of “Mr. Tambourine Man” and “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.”

Suddenly, the mood is broken by the shouting Abdullah standing on stage and addressing the “white cats” and “black cats.” Oddly, in attacking Wilkerson’s presentation, he doesn’t emphasize Allah, but rather the advantages of gang life. Yeah, there’s a winner. He reminds everybody that the exits are shut off, and that the two gangs came here to rumble. At his words, everyone starts watermelloning and pulling out their weapons. (This is apparently an easily swayed crowd.)

The two gangs start toward each other, as Wilkerson looks to Heaven for a miracle. And it comes. (Otherwise, it wouldn’t be much of a movie.) The miracle takes the form of Nicky, who’s found the Light and intercedes between the gangs. Proclaiming that Jesus is in the room, Wilkerson orders them to put away their weapons. “C’mon, with all of your hang-ups!” he cries, inviting them up on the stage.

With this, the two gangs come together. Their rapprochement is indicated when Big Cat and one of the Mau Maus solemnly high five each other. (And yes, it’s just as goofy as that description sounds.) Nicky, meanwhile, hugs Bo in a sign that he’s found the Path. Out in the audience, a watching Rosa cries with joy.

Her expression soon turns into a rather comical look of horror when, to a blare of music, she sees Abdullah flip open his switchblade. He attacks Nicky by slashing his hand. (You’d think a ‘warlord’ would be able to use a knife in a more efficient manner.) Nicky, however, soon has Abdullah on the ground, threatening him with his own knife. Needless to say, though, Nicky then makes a show of sparing his life. Speaking for much of the audience, Abdullah notes that “I really don’t dig this scene!”

As if to make sure that any credibility the scene has built up is wasted, those annoying minstrels return to the soundtrack. “God loves you / He loves you / Just as you are, now standing there / In your cold, dark and bitter little world / He loves you / He loves you-oo-oo / His hand, is reaching out / oo-oo-oo…”

Meanwhile, Nicky and Wilkerson exchange exactly the kind of ‘crying with joy’ expressions as the goony lead characters of The Promise did at the conclusion of their picture. As Nicky proclaims his new focus on Jesus, the minstrels ‘oo-oo’ in the background, finally noting that “God’s Love is stronger than anything! God loves Nicky Cruz. God loves Nicky Cruz!!” Yeah, thanks, now I get it.

Wilkerson starts to hand out Bibles. The gang members, thirsting for Spiritual Sustenance, hungrily reach out for them. Unfortunately, the director emphasizes this by having the actors act in a childish, “oo, oo, give me one!” sort of fashion that recalls the kids in the candy shop demanding sweets in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory.

Now comes an especially embarrassing moment. Focus is drawn to the actor playing the formally ultra-cool Big Cat, apparently here directed to act exactly like a wide-eyed five year old. (They’re young in their newfound innocence – get it?) “Hey, hey, Preach?” he stutters. “How about giving us one of those big [Bibles] so that you can really see what we’re carrying!” “Preach, me too!” concurs Israel. Goshers, yes!

We cut to Rosa, tying a bandage around Nicky’s bleeding hand. Rosa notes the difference in him, how he’s “bright…all kinds of shiny!” “Maybe it’s because I’m about two minutes alright now!” he answers, sort of. Then the reformed duo hug, letting the audience know that they’ll live happily ever after. Israel, meanwhile, is looking through his Bible and happily notes that his name is “all over this book…I’m practically on every page!”

As the camera zooms in on Wilkerson, truly odd ‘computer’ music is heard. I suppose it’s supposed to be ‘cool,’ but it’s more like something that you’d hear at the end of some sci-fi picture like The Forbin Project. However, it quickly segues into more appropriate ‘happy’ guitar cords. Wilkerson’s voice is heard: “So, this was the beginning.” (Don’t worry, he’s not talking about the movie.)

We learn that this “breakthrough” made “the ghetto my church.” He’s last seen walking past winos and knife wielding thugs. His narration explains how his outreach techniques spread across the land, helping others like Nicky and Rosa. “You can take it from this skinny preacher from the hills of Pennsylvania,” he sums up. “The Cross is mightier than the Switchblade.” And so the work of David Wilkerson continues. Which is fine. As long as his movie is over.

IMMORTAL DIALOG: