A Jabootu Sponsor’s Pick

Prologue: If you have ever wondered (and really, who hasn’t?) why I dropped sponsored reviews, here’s the scoop. See, I have just enough of a conscience to be embarrassed that I’m a dick, but not enough to actually stop being a dick. And since I proved constitutionally unable to finish such pieces in any reasonable amount of time…

Cast in point. Sometime during the administration of the first President Bush, one Katherine Evans foolishly sent me money under the premise that I would, in fact, review the film she’d requested, a zany sci-fi flick called Voyage to the Planet of the Prehistoric Women. I was confused, actually, since I had always conflated this title and that of Women of the Prehistoric Planet. I was therefore excited to have another crappy film pop up on my radar.

However. Aside from being terminally lazy and unfocused, I am also on occasion overly ambitious. This is a bad combination. Thus when I discovered that Voyage to the Planet of the Prehistoric Woman was constructed from bits pillaged from the Soviet film Planeta Bur, and that further that film had previously been reshaped into another film, Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet (adding further to my title confusion), I decided that I would review all three movies.

Initially please that she was, apparently, getting more bang for her buck (despite generously sending me more money with which to buy a bootleg of Planeta Bur), Ms. Evans failed to see the danger. Sure enough, even though her requested article finally approaches being posted–following a Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet review–it was at a bitter cost. She sent me payment so long ago that if she had instead invested it in T-Bills she’d have an extra $47,000 by now.

But hey, the end is in sight. So here’s the first of Ms. Evan’s three pieces. A few days from now, she’ll even get the one she actually asked for…

********

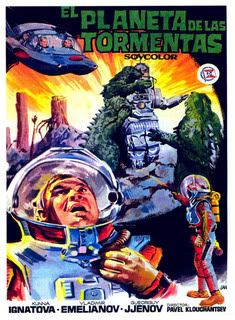

WARNING!!! EVENTS DEPICTED IN POSTER MAY NOT ACTUALLY OCCUR IN FILM.

The Soviet sci-fi meller Planeta Bur (1962), or Planet of Storms, is by no means a classic. Still, it has points of interest, and only partly because of its exoticism. It initially seems a rather dour space exploration movie, reminiscent of 1950’s fatalistic Rocketship X-M. Once the cosmonauts make planetfall, however, the film suddenly becomes a zany wonkfest on the order of such goofy fare as First Spaceship to Venus or Angry Red Planet. I’d suggest the influence of Edgar Rice Burroughs was being felt here.

As we open, State Radio is reading an announcement from TASS about the Soviet People’s latest triumph in space. “Attention!” the Announcer commands. “Moscow calling!” With all good Soviet ears presumably turned to, the Announcer explicates the situation. Three “astro-ships;” the Sirius, Vega and Capella; are currently in orbit about Venus.

Seconds later, however, the Capella is wiped out by a meteor strike. The odds against such a thing occurring are, well, astronomical, but anyway. We cut over to the Sirius, where that craft’s three-man crew (and I have to say, the actors here are rather less, uh, glamorous than you’d get in an American film) sits around and mutters darkly over the situation. “To have come so far and to die near Venus,” one muses. “We are still powerless against big meteorites,” another notes. Yes, good thing the odds of getting hit by one are literally…oh, right.

They are interrupted by a message from Earth. This expresses faith in the remaining cosmonauts’ courage, and orders them to “investigate conditions” on Venus. (“Be on the look out for any and all counterrevolutionary one-celled organisms, which must be compelled to join into collective dialectic action!”) They also learn that a relief astro-ship, the Arcturus, will leave Earth the following week.

The men discuss the implications. The Arcturus won’t arrive for four months. However, the original exploration plan requires three ships: one to stay in orbit with extra fuel, while the other two (“for safety’s sake”) are to land on the surface together. The idea is that they are meant to wait for the third ship and proceed as planned, although it seems unlikely they would have the means to orbit Venus for four months before proceeding.

It’s probably best to try to establish our cast here, since several characters sort of blend together:

- Vershinin is the most veteran, and seemingly mission leader. (Sirius)

Roman Bobrov is A Guy. (Sirius) - Alyosha is the youngest fellow, and naturally the most impetuous. (Sirius)

- Ilya Shcherba is team leader of the Vega.

- Kern is the apparent technology guru. (Vega)

- Masha is the woman. (Vega)

Alyosha balks at this latest set of orders. The other ship, the Vega, has a “glider” capable of reaching the planet under its own power. He suggests using this to head to the surface immediately. Vershinin points out that the glider would not be able to leave the planet. Alyosha agrees, and proposes that he should land on Venus and work there until the Arcturus arrives. At that point two astro-ships would descend to the surface together, as originally planned, and meet him. He also argues against just sending down the Robot they’ve brought with them. “Someone’s got to see Venus with his own eyes,” he says. He stalwartly assumes any risk that comes from following his suggested path.

On the Vega, the other crew debates this proposed scheme. One of these is Kern, the designer of Iron John the Robot. John is rather interesting. Obviously inspired by Robby the Robot from Forbidden Planet, down to his robotic speaking voice, he’s realized with a marvelously elaborate exoskeleton-type suit, which seems to move hydraulically. This thing must have been an almighty pain in the ass for the actor inside to maneuver around, but it is pretty cool.

Masha, the lone female cosmonaut, remains upset by the deaths of their fellows. Kern* is more coldhearted. “They were lucky,” he shrugs. “Instantaneous death.” Moving on, he wonders why the Vega should surrender its glider so that someone from the Sirius can land on Venus. Still, they agree, or at least the two menfolk do, that somebody should go down. “Better to die usefully,” Shcherba says, “than to wait for a meteorite to hit you, or radiation disease to get you.” Being a woman, Masha is made nervous by this impetuous talk, but Kern retorts “Risk is standard behavior in space.”

[*I suspect Kern is meant to be American, or at least hail from some capitalist nation, presumably as part of international outreach on the part of the Worker’s Paradise. Aside from his non-Russian sounding name, Kern once uses the ominous phrase “my firm”, and is the one who’s brought John along. Several of the other crewmembers, meanwhile, view John at least somewhat darkly. Apparently using a technological artifact in place of humans denies a larger, glorious human triumph. Then there is the fact that Kern is the most cold-blooded of the bunch, perhaps another sign of his lack of progressive tendencies. This is all conjecture on my part, though.]

Shcherba suggests that Kern use John to compute the best formulation for a landing, given their present circumstances. Kern activates John and gives him this order. “Ignore the danger factor,” he instructs. John suggests that the Vega stays in orbit “with one man.” (Oddly sexist language from a robot, you’d think, much less a Soviet one…if he is.) Meanwhile, three ‘men’—including John—would head to the surface in the Vega glider, while the Sirius itself would also land with a crew of three.

The Sirius would eventually return to orbit with five crewmembers, leaving the sixth on the planet. That seems to be just about the most ridiculously convoluted plan one could come up with, but then I’m not a robot. John suggests that he be the one to remain behind on Venus, being “dead” (or so the subtitle reads; I’m assuming ‘lifeless’ was closer to the mark) and heaviest.

“Mathematics is pitiless,” Kern observes in response. Masha’s reaction, needless to say, is more intuitive. “A rotten plan,” she dubs it. “A good plan,” Kern retorts, “but dangerous.” If you say so. That doesn’t seem like a very logical objection, however, considering that Kern ordered John to “ignore the danger factor.”

Masha’s reaction, in contrast, is apparently triggered by the fact that (supposedly) the plan’s logic dictates that she be the lone person to stay in orbit. Nearly overcome by emotion, she observes, “No one else can process the information and transmit it to Earth.” If that’s true, they didn’t do a very good job of cross-training.

This isn’t what Masha had hoped for, and she grouses about years of training spent to just end up staying on the ship. “I worked so hard…so many years…” she kvetches. As well, it seems possible that she’s romantically involved with Shcherba and had wanted to experience this with him. Shcherba points out, though, that the “international association insists on the Robot.” (Ah, that substantiates at least somewhat my thoughts on Kern and John.) In the end, of course, the Glory of the People overshadows the wishes of any individual, and Masha bucks up.

Later we see Masha gazing out a port window as she records her thoughts on the planet below. The scene proves that there was no significant Clunky Exposition Gap between our cheesy sci-fi flicks and those of the Soviets, as this is naturally used to establish a number of things for the audience. Via “automats” previously sent to Venus’ surface, “We’ve studied the atmosphere, discovered oceans and continents,” and so on. “But the automats don’t tell us the main thing,” she muses. “Is there life there?”

Next the cast (supposedly) reads various gauges and records sundry bits of highly dubious ‘scientific’ data. “Cloud altitude 15,” Alyosha announces. Most interesting is a mysterious red glow somewhat detectable through the planet’s roiling, cloudy atmosphere. “Perhaps the red glow is a lighted city,” Alyosha suggests. Kern, as usual, is more acerbic. “It’s a dead planet,” he predicts. “Intelligence has already destroyed itself.” Sort of a bold prediction, really, considering the utter lack of data supporting any such conclusion. But then we Americans are a dour, pessimistic people.

Later, Shcherba radios Vershinin and explains that no apparent landing spot for the Sirius can be found through the cloud cover. Shcherba fills him in on the plan Iron John formulated. He, Kern and John would take the more maneuverable glider down first, and locate a spot for the larger Sirius to eventually land. They’d all explore and then return to the Vega, leaving only Iron John behind. John would work to set things up for the larger mission to resume after Arcturus arrives. At a loss for a better plan, Vershinin signs off on asking permission to pursue the idea, although Roman dubs the scheme reckless.

Cut to Shcherba and Kern suited up and preparing to leave, while Masha mopes in the background. She and Shcherba kiss before he leaves, so apparently they are an item. Then the glider is seen falling towards Venus, while Masha tearfully looks on. Meanwhile, the crew of the Sirius tracks the glider. After the boat enters the cloudy atmosphere, control of the vessel is given to John.

Unable to penetrate the atmosphere, Shcherba uses their instruments to locate a suitable landing spot for the Sirius glider. However, buffeting winds carry the glider away, and they report that they are being forced down over a swamp. (Again, we hear about all this rather than see it. Perhaps the film was produced by Roger Cormanskovich.) “Projecting rock,” Iron John mechanically announces. “Chances of destruction 90%.” After that the radio suddenly kicks out. Those remaining in orbit are naturally distraught, especially Masha.

Unable to contact the glider, Vershinin eventually decides they will go ahead and land the Sirius and mount a rescue operation. He radios Masha to inform her of this, and tells her to monitor them. Making sure the others aren’t listening, he warns her that if they die, she should “keep herself in hand.” She acknowledges his orders and ends the call. “It’s always hardest on those left behind,” Vershinin muses.

As they prepare for their mission, they receive a call from Earth. This informs them that they have permission to return home is that’s their choice. “People are what counts,” they are told. And boy, if the Soviet Union stood for anything, it was that principle. Needless to say, however, the stalwart crew goes forward with their plan. “We assure the Soviet government, Party and people that we’ll do all we can to justify their trust in us,” Vershinin replies.

Next we get a pretty basic landing scene, including some goofy but fun model f/x intercut with the actors assuming strained expressions to indicate the rigors of increased gravity. Eventually the Sirius lands in a thick (not to mention economical) cloud of dry ice fog. “So this is Venus,” Roman gasps in wonder. If he’s excited now, wait until he can actually see it.

They turn on the exterior microphones, and are bewildered, as am I, to hear an assortment of Forbidden Planet-esque electronic sound effects. There’s also what sounds like a female opera singer making ghost sounds. The sounds fade out and the guys get back to work. Vershinin orders Alyosha to contact Masha once her ship comes back over the horizon.

At dawn the next day, they don (fairly believable) spacesuits and commence their search for the glider. The land is still shrouded in fog, but not so much, probably because by now they’re not looking over a tabletop model. The first out of the ship, Alyosha gleefully announces that the ground is firm and asks permission to take a little jaunt. Vershinin agrees, and off he goes. He quickly finds a standing pool of liquid, and dipping his gloved hand in it, pronounces it “ordinary water.” Yeah, screw those time-wasting chemical tests. What else could it be?

He soon is separated from the ship by the fog, which is pretty quick work, I must say. He hears Vershinin order him back, and turns to obey, whereupon the film goes in another direction entirely. Up to now it’s be a fairly sober and realistic space exploration drama. Here it heads straight into b-movie land, as Alyosha finds (what else?) a rubber tentacle wrapping around his ankle.

He unsheathes a knife, and tries to hack away at the thing right near his ankle. This wouldn’t be my first instinct, especially since, you know, he’s currently wearing a spacesuit. In fact, the whole belt knife thing doesn’t seem a very good idea to start with. Not that it really matters, because he almost immediately loses hold of his blade. After this, the tentacles pull him from sight behind a rock.

Inside the Sirius, Roman tells Vershinin that Masha has located the glider. She was unable to contact the crew, but did track a moving metal object, presumably Iron John. Hereabouts the guys hear the scat singing opera singer again. Startled, Vershinin tugs on Alyosha’s line, and when there’s no response, he and Roman rush to investigate.

Following the rope, they soon find their crewmate in the clutches of a pretty standard Giant Bulbous Carnivorous Plant, complete with flailing, wire-manipulated tentacles. They draw their own knives and also start hacking at the tentacles binding Alyosha, a strategy which might explain the lack of successful Soviet manned space exploration missions. After a fairly rote tussle, they pull Alyosha free and book out of there. “The spacesuit’s whole,” Roman announces after a quick examination. Yeah, no thanks to you, buddy.

“There’s life here,” Alyosha cheerfully gasps. “That’s the important thing.” Well, he’s a game one, you’ve got to give him that. He asks how they knew he was in trouble, and Vershinin replies that they heard a shout. (They thought the opera woman voice was Alyosha?!) “So did I!” Alyosha agrees. “Anything’s possible on Venus,” Roman shrugs. Yeah, there’s the scientific spirit.

Having returned to the Sirius, Vershinin radios Masha for further details. In response, she gushes like a girl in her joy over having located the glider. “I sang songs and then I flew around the cabin,” she laughs. “I took off my magnetized shoes and flew!” So saying, she pushes away from her console and begins *cough* floating again, albeit in an awkward fashion suggestive of an Earth wire rig. Not that I’m saying anything, I’m just saying.

Back on the Sirius, Vershinin grimaces over Masha’s girlish tomfoolery. “We’d like the details,” he says. “Sorry,” she replies. “I lost my head.” Yes, your pretty little head. We understand. Bringing a girl into space is like bringing a little monkey with his own little spacesuit. When it starts chittering and engaging in mindless hijinx, you can’t really blame the monkey.

In any case, following Vershinin’s mildly exasperated response, Masha calms down. She reports that the glider is “32 km. away from you, across the gulf.” Hearing this, Vershinin orders Roman to ready the “cross-country car.” Man, that’s one well-supplied exploration party. “That’s a long distance for it!” Roman protests, which somewhat mitigates the ‘cross country’ designation, but anyway. Lacking a better suggestion, however, Roman goes to get the vehicle prepared.

Meanwhile, Masha confirms that Iron John’s movements indicate the others are alive. He wasn’t fully assembled when the glider left. If he’s moving now, they must have finished putting him together on the ground. And sure enough, cutting over to their location, we see that this is so. Iron John is staggering around over the uneven terrain, and you certainly feel sympathy for whoever was stuck into the suit. Even so, this is our first chance to really see the suit in action, and it’s clunky but impressive nonetheless.

Kern is seemingly calm, while Shcherba fires a wee little pistol at unseen forms flitting around in the fog. Then we do see them, and they are guys in some amusing reptiloid costumes. As Shcherba is attacked, Kern fires too. He has a much larger pistol, perhaps a Lugar. So maybe he’s German (West German, presumably). Several Reptiloids fall, but several more prance around in the background. Shcherba begs Kern to hurry, as the latter is, I guess, finishing Iron John’s assembly. “That was some blow, John,” Kern muses. I can only assume he’s talking about whatever substance the writers were doing when they wrote this script.

Kern finishes, and sets Iron John off in a certain direction. John wades through the Reptiloids while trailing a cable. “Ordinary men cannot conquer these wild planets,” Kern observes, again marking him as an inappropriately cynical fellow. Meanwhile, John has gotten past the Reptiloids and achieved a position higher up on the other side. This allows Kern and Shcherba to (presumably) similarly bypass trouble by clambering along the cable, although for obvious logistical purposes we cut away before any actual stuntwork is portrayed.

We cut to the Sirius crew, whose vehicle proves to be a bubble car. Nothing says The Future! like stuff shaped like a bubble. The device floats over the ground, like a hovercar, although I can’t imagine they actually had a working one. Presumably it moved on a wire or perhaps a rod, although if so they hid it well.

They stop, because they’ve seen—that’s right—a dinosaur. (Stop action, happily enough.) “Looks like a brontosaurus,” Roman enthuses. “I’ll get a blood sample,” he says, drawing his pistol. (!!!) To be fair, I’m pretty sure a beast that big, and with such a primitive nervous system, wouldn’t even feel getting hit with that popgun. Still, Roman’s got a lot of balls. Andy they do get the nervous system part right. Only well after Roman has left the area does the dinosaur appear to feel the bullet.

By the way, this is awesome. Reptile guys in rubber suits, killer plants, robots, spaceship models, hovercars…man, that’s good crap. And we’re only half an hour into things.

We cut back to Team Glider, who are stumbling around and looking a bit worse for wear. Except the Robot, of course. Kern tells Shcherba to slow down and preserve his oxygen, although he himself (Kern) doesn’t believe the others will come look for them. “People are natural cowards and egoists,” he opines. Seriously, would a guy that cynical even get on a space mission? It seems unlikely. Don’t they do psych screenings for things like that?

Shcherba, in contrast, is a Proper Soviet and knows different. “People are natural friends!” he exclaims. Except for capitalists and Kulaks and Jews, presumably. However, the Great Debate is forestalled when a gasping Kern adds “We’ve caught malaria.” (!!!!) OK, if you say so. “Infection has got in,” he continues. “We’ve torn our suits badly.” Er, then wouldn’t you be dead already? How are you advising Shcherba to preserve his one day of oxygen when his suit is torn? And how do you know it’s malaria, for Pete(rovich)’s Sake?

“Let’s take some quinocillin,” Shcherba replies. Is ‘quinocillin’ even a word? Maybe…IN THE FUTURE!! However, taking quinocillin apparently demands a protracted rest period. They don’t have time for this now, and so Kern suggests they just power through it. “It will pass,” he shrugs. Because that’s one of the hallmarks of malaria, I guess.

Back to the Bubble Car Bunch. Given that the trip to the other shore is far shorter by cutting directly over the water, they head in that direction. Before doing so, however, they again hear the unearthly singing, and get out to give it a good listen. Being an Exaggerated Rationalist, Roman dubs it “A squid of some sort. There are plenty of vermin around.” I never knew that squid qualified as vermin, or sang for that matter, but there you go.

They stroll around for a look, leading to a Grand Philosophical Discussion. Vershinin and Alyosha think the voice sounds human, an idea Roman instantly dismisses. “You’d better recall Darwin!” he scoffs.* “How can man appear in the dinosaur period?” Actually, it isn’t Darwin who suggested that Man and dinosaur didn’t exist at the same time, but the fossil record. And, oh yeah, you guys are now on an entirely different planet.

[*This is actually kind of a funny analogue to an overtly religious crewmember in an American sci-fi movie who might quote the Bible to spuriously support a scientific assertion.]

Alyosha replies that they themselves are here, but again Roman sneers him off. “We flew here,” he points out. However, Vershinin supports Alyosha’s observation, theorizing that humanoid aliens may have come here long ago and settled on the planet. “Man is a space flier,” he maintains. “Darwin’s theory applies to Man’s evolution, and not his distribution among the planets. That’s in Tsiolkovsky’s field.” Man, don’t you usually need a ton of pot to fuel conversations like this?

Vershinin is referring to Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, an extremely early theorist in space and rocket travel. Tsiolkovsky was a pioneering advocate of the idea that to survive, man would have to colonize space. Still considering the idea crazy, Roman sniffs, “I wonder why they keep you in the Academy of Sciences?” Vershinin chuckles in an avuncular fashion. Being at a philosophical impasse, they decide to continue their journey.

Cut to Party Glider traversing some rocky terrain through pouring rain. (Actually, I think they’re just in a waterfall area.) I again felt especially sorry for the guy stuck in the Iron John suit. “There’s too much water from above,” John echoes, presumably because the word ‘rain’ wasn’t programmed into his Space Lexicon. As this poses a danger to his interior mechanisms, he proposes they find shelter.

Kern and Shcherba, who are about ready to pass out from fatigue and illness—I guess the malaria didn’t ‘pass’—concur. They order John to find a cave, and he quickly complies. Stumbling along and with Kern all but carrying the more nearly incapacitated Shcherba, they follow and fall to the floor, gasping. Meanwhile, John starts babbling, perhaps having been somehow damaged by the rain. He’s not alone, though, as his organic companions begin issuing fevered ravings as well. Kern rants that “By mathematical laws there will be a world government…” John picks up this thread. “World government…world advantage…world science…” he intones. Shcherba, meanwhile, believes he is talking to Masha.

As John drones on nonsensically, reacting to the mutterings of Kern and Shcherba, we cut back to the Bubble Car. It is currently (if none too convincingly) moving over the lake. The crew is concerned to learn that John has disappeared from Masha’s locator. However, they are now close enough to John that Roman picks him up on their radio. He reports that John is spouting nonsense.

Vershinin assumes this means that John is not currently under human control. Roman attempts to contact John, who doesn’t answer. “The devil doll doesn’t answer,” he gripes. Vershinin explains that John “reacts only if politely addressed.” (!!) I assumed he was kidding, but Roman assumes a sarcastically sweet manner, and John indeed responds.

“Where are your masters?” Roman inquires. “No masters,” John replies. “Slaveholding is forbidden by the Constitution. I am a free, thinking machine.” Robots are allowed to be pedantic, I guess. Even so, Roman gets the lowdown on the situation. Hearing that Kern and Shcherba are raving incoherently, Vershinin instantly deduces that they’ve got malaria. Really? Why malaria? Don’t you get fevers with other diseases? Anyway. They successfully order John to feed Kern and Shcherba quinocillin pills from a wee little bottle. We actually see this accomplished and the process is pretty clumsy, given the constraints of the clunky robot suit.

The car is soon attacked by a big puppet pteranodon, which is lovably goofy. This makes a loud honking sound, which isn’t exactly helping any. Well, OK, it’s helping, but only in a Giant Claw sort of way. “Pull down your helmets,” Vershinin orders. “It’s dangerous!” Gee, ya think? Good thing he’s in charge. Anyway, they drive the bird off with a Whammo Air Blaster they have mounted atop the car. Whew, that was…too close.

However, their antediluvian attacker is undeterred. They radio in the situation to Masha, and report that their car has received a heavy blow. After this they fall out of contact, much to Masha’s distress. Thus she doesn’t know that they’ve taken a severe course of action. Being unable to otherwise evade an imminent fatal attack, they open a scuttling port set in the car’s floor (!) to sink both the vehicle and themselves.

Meanwhile, all a shocked Masha knows is that they have disappeared from her sensors. “The car is not designed for underwater,” she thinks to herself. “What if they’re hurt?” As you can imagine, this entire situation is a script contrivance, purely meant to set up a dramatic situation. For if a robot like Iron John is presently going nuts, you can imagine how a mere girl like Masha is doing. Especially worrying at her is that she is now out of contact with both teams. Without a man to tell her what to do, she’s kind of freaking out.

Sure, she has standing orders, which are to remain in orbit. However, these just seem so…emotionally unsatisfying. “My heart tells me [my stranded comrades] need me more,” she thinks to herself. She’s tempted, perhaps overwhelmingly, to land the Vega on the planet and see if she can somehow help. The downside is that this would not only put them out of contact with Earth, but also strand everyone until and if relief arrives months later. With the Vega also landed, they would have no mechanism for returning home on their own.

Then there’s the issue of her responsibilities to The State and its people. “The Earth…” she muses. “Millions of people worked, making a pyramid to the sky of their work…Now everything depends on me alone.” In the end, however, she’s a female. She records a message on a reel to reel tape recorder, which presumably functions as the ship’s log. “The instructions forbid withdrawal from orbit,” she admits. “But why save fuel if the men are dying? The instructions could not foresee everything. My heart tells me they need me more.”

The next step is to inform Earth of her decision, which can be executed in one hour when she next passes over the area. “How hard it is to speak calmly,” she thinks. “Let them listen to my last recording.” And so she transmits the tape she just made. This draws a quick and terse response from the Stentorian Earth Voice. “Hello!” it booms. “Vega! Masha Ivanova! Earth is with you! Take yourself in hand!” In other words, stop acting like a silly goose, girlie.

The orders not to leave orbit are reiterated. “Earth asks you!” the Voice continues. “Your Earth!” Apparently Ground Control realizes that an emotionally based request will work best with a member of the fair gender. “My Earth!” Masha whispers, indicating this is so. Conflicted, Masha thinks of various things. Images of throngs back on Earth cheering during a parade clash with ones of her fellows perishing on the surface below. “What shall I do?” she gasps, tearfully. “My time is nearly up! I must decide! I cannot!” Ah, the eternal question. Where do ‘must’ and ‘cannot’ meet on the graph?

Cut back down to the Venusian sea or lake or whatever it is. On the water’s floor, the Sirius crew is manually ferrying their car along. Oddly, they seem to have less problem than you would think lifting the vehicle up to waist level and carrying it along. This scene is a standard piece of trickery, with the action taking place on a befogged set which is shot through a water tank. Still, they do a pretty good job of it.

They decide to take a break, and naturally Alyosha wanders off to do a little exploring. This is motivated by him exclaiming, “Interesting boulders!” as he looks over some entirely standard-looking foam rubber rocks. Nobody stops him from going, despite the fact that they’ve already suffered several near fatal attacks from the local flora and fauna in the short time since they landed here. Meanwhile, his mates comment on how amazingly the local fish and stuff look like Earth ones. Apparently they realized even the kiddies in the audience might be noticing that.

Roman, the Darwinian Skeptic, muses on other issues as well. “Surely,” he thinks, “nature could not have made such an even row of cliffs. What if it is a sunken city?” Meanwhile, Alyosha gets a false scare from a dog-sized octopus puppet, which quickly shies away. (An oddly realistic reaction, I must say.) This part of the action might actually have been filmed in a water tank, given the way both the actor and the puppet bounce around. Again, the director obviously really put a lot of work in on this movie.

Alyosha then sees an open cave, and naturally sticks his head in it. “Hope the owners are out,” he quips, this again being the guy nearly eaten by a plant less than a day earlier. Inside the cave, he finds a strange rectangular-shaped rock and takes it along.

He returns to the others, to learn that Roman has found what he calls a petrified dragon. Still resistant to the idea that men-like creatures exist here, it is Vershinin who proposes that perhaps it is actually a sculpture. He proves this by uncovering an ‘eye,’ which proves to be a set ruby. “Put in by a rational being!” Roman gasps. Here they set off again. I must say that this sequence is a nice little mood scene. It doesn’t knock your socks off, but setting it underwater does oddly give the business an authentically alien feel.

Back to the Glider Guys. Kern is up and about and whistling, apparently cured by the quinocillin tablet Iron John gave him. Shcherba is also seemingly recovered. They get together and theorize that volcanic activity is leaching oxygen from the Venusian air. “Man can change that,” Shcherba suggests, a fairly early mention of terraforming in cinematic sci-fi. “Want to win the Nobel Prize?” Kern scoffs. “One can work for mankind without prizes!” Shcherba responds. Stout (Soviet) fellow!

Meanwhile, Iron John is preparing, in a rather ingenious bit, to make a bridge over a nearby chasm. He has rope lines which emanate from his torso, and he’s tied one around a large tree and anchored himself with others to a rock formation. Then he repeatedly rotates his upper half (in a manner that would be impossible if an actor were currently in the suit) to reel in these lines, pulling the tree down and over the gorge.

The film’s director used tricks like this earlier, too, in which Iron John did things in a way that undercut the guy-in-suit idea. For instance, there was a bit in which Kern opens a panel in John and reaches his hand all the way through a panel on the opposite side. Like a magic trick, you can figure these things out if you think on it, but the initial effect is still nicely achieved. At Kern’s request, John acts like a jukebox and plays a cheerful little jazz tune. Then we get a long shot of the three of them traveling over the tree above the deep gorge. I’m assuming this is via a matte effect, but in any case the trickery is nicely achieved.

Meanwhile, the Sirius crew and their car have finally reached a beach. They haul the car up on the sand. I’m still not sure how they moved this thing around so freely, even if Venus has a lower gravity than Earth, and I’m not sure it does. In any case, unsurprisingly, we don’t actually see them haul it free of the water and up on shore. There’s just a cut and the car is resting there.

For some reason (i.e., IITS), the car will again function perfectly once it “dries,” and so they leave it in place and sit around a fire. There Roman still seeks to defend his Darwinist dogma. He admits the existence of the dragon statue is startling, but suggests the carving was “crude,” and arguably the work of “a savage,” rather than an indication of an advanced species. Huh?

Vershinin also continues to argue for his pet theory, noting that “savages couldn’t have flown to Venus.” “Why not?” Alyosha laughs. “Bobrov flew here!” Vershinin isn’t to be distracted, however. “Savages couldn’t have flown here,” he continues, “but they could have appeared on the spot. Suppose civilized beings had flown here and remained for some unknown reason and lost contact with their home planet.”

Needless to say, this scenario nearly mirrors their own. (And will do so completely, should Masha indeed elect to land on Venus herself.) Such visitors might have remained stranded and, would, eventually, through the generations “go wild in the brutal fight for survival…only the strong would survive.” Alyosha jumps in, adding, “And savages would appear among the dinosaurs!”

He and Vershinin continue in this vein, adding that this would allow for already manlike hominids to be on the scene “before the apes appeared and the future master of the planet began to evolve.” Again, that all seems like a lot of conjecture given the evidence currently at hand. And I’ve again not convinced Darwin meant to establish an iron-clad rules that man and dinosaurs could not exist together under even radically different circumstances—but there you go.

They halt upon hearing an eerie, gibbering, singsong call. “Sounds like a warning!” Alyosha remarks. (Uhm, OK.) “We’re near the red glow,” he continues, which they had earlier spotted from orbit. This breaks up their confab, although Alyosha continues personally musing on the mystery. “On Mars every drop of moisture is a problem,” he notes. “Here there is water everywhere.” Yes, it’s almost like we’re talking two entirely different planets.

He begins wondering if these travelers to Venus might have also visited Earth. “We modern people…” he begins thinking, although he is interrupted as the announcement is made that the car is ready to depart. He joins the others as they depart, but vows “I will find her!” He’s referring to the owner of the supposed voiced they’ve been hearing.

Alyosha’s thoughts on extraterrestrial colonizers remained a familiar theme in sci-fi and popular culture during this period. Most prominently, a similar concept was advanced by Nigel Kneale in his 1958 teleplay for Quatermass and the Pit, itself made into a fantastic movie in 1967. More lucratively, Erik von Däniken made a lot of money pushing such theories in a series of books, beginning with 1968’s The Chariots of the Gods.

Back to the cave, where Shcherba and Kern appear to be fully recovered. “It’s getting dark early,” Kern notes. I’m not sure what his frame of reference is, but anyway. “There’s a cloud of ashes over us,” Shcherba replies. This is from a nearby volcanic eruption (which Kern can clearly see, so his ‘getting dark’ remark is a bit weird). This then explains the mysterious red glow. “Your lighted ‘city'” Shcherba laughs.

Kern notes the obvious, that being in close proximity to an erupting volcano is “rather inconvenient.” Shcherba is just excited, though. “We can get samples of lava and ashes,” he happily replies. The prosaically-minded (or perhaps crabbed) Kern suggests moving away to a safe location. The more poetic Shcherba agrees, but with regret. “A pity to leave this magnificent spectacle,” he sighs.

There follows a modestly spectacular runaway lava sequence, which really must have pushed the filmmakers as far as they could go. Shcherba indeed collects samples of this, and again Kern is the one who must suggest they get themselves to safety. They are soon surrounded by a stream of the stuff though. Kern orders John to carry them to safety “across the river of flame.” I guess he has a poetic streak after all.

They climb upon John’s shoulders and the robot begins wading through the ankle-deep stuff. Man, I hope his metallic chassis doesn’t conduct heat very efficiently. As they move away from the rocks, John’s sensors begin working more efficiently. He reports that the search party is only two miles away.

However, John’s programming problems kick in again, and in a most inconvenient manner. “The heat has reached 500 degrees,” he volunteers. “Further movement with a load endangers my mechanism.” Kern tells Shcherba to reach inside “panel 5” and turn off John’s self-preservation circuits. In response, John starts trying to chuck them off, and begins crushing Kern’s leg. You know, this is exactly the sort of thing Asimov was trying to avoid.

During the struggle, as the men search for the proper wire to pull, the car approaches. The search party immediately kens the situation, which speaks well of their deductive abilities. Anyway, a wire is pulled, and John begins playing swing jazz (shades of HAL) and then shorts out entirely. Good design work, Kern. This leaves the two high and dry, and the hover car is sent over the lava (!) to rescue them. Soon after, John topples into the increasing lava flow, a mute, melancholy testimonial to the inferiority of technology over the human spirit. Even a wiser Kern now admits that man must be part of the equation.

Later, back on the beach, they wait to hear from Masha. Bobrov’s wife, we learn, had triplets just before they left Earth, and a picture shows them identified as 1 to 3. “Why are they numbered?” he’s asked. I assumed the answer would be either “For the greater glory of The State!” or “Gwyneth Paltrow suggested it.”

However, the solution is more prosaic. “We hadn’t named them yet.” This is the movie’s idea of comic relief. “Daughters?” a chucking Vershinin asks. “Sons,” Bobrov replies, slightly affronted. (This never came up during their long space voyage?) “A compete crew!” Vershinin observes. Ha! Good thing they weren’t girls, then!

Meanwhile, Kern and Shcherba—I think, the helmets make identifying who is who kind of a pain in the ass—are off to the side continuing the intelligent life debate. Vershinin joins them, suggesting “Many of history’s mysteries could be evidence.” That would sound reasonable, if I knew what it meant. Said mysteries include, apparently, “the stone age drawing on a cliff in Sahara.” Vershinin enthuses that “It shows a man wearing something like a space suit.”

Again, this is ground that von Däniken would later cover in his books, as is much of the remaining examples proffered here. Then Vershinin begins arguing that space flight is a natural stage for intelligent life anywhere. Heading off with his thoughts, as is his wont, Alyosha begins daydreaming again.

“The migration of life in space is as natural,” he thinks via narration, “as seed swept by the wind on Earth. And the branches of a single tribe of living beings are developing in the solar system…then rational beings must be related.” Well, not really, but anyway. And man, this is pretty chatty (or philosophically-minded, if one is more generous) for a space opera.

Alyosha’s desire to see his imagined Venusian woman is now at a feverish peak. “Everything would become clear,” he thinks. Then he is attacked by a gill man-type monster—but it is only a mischievous Bobrov (I think) covered with ferns or something. On this jocular (sort of) note the scene finally ends.

In the next shot their journey has resumed, and their trundling car is accompanied by the sort of cheery orchestral music that in American films would herald an industrial short on the centrality of feldspar to Modern Civilization. “Why, you wouldn’t have that household cleaner [box winks out of existence] if it wasn’t for feldspar! Ready to start your day? How would you drink that coffee with [wink!] no ceramic mug?”

Soon the soundtrack breaks into a merry, albeit untranslated, Russian song as the crewmembers do various exploring stuff. We see a lizard, a stop-motion Apatosaurus and other prehistoric reptiles (you really have to wonder at the amount of time they spend grabbing water, rock and lichen samples, as opposed to studying the dinosaurs).

Then, these vital tasks apparently completed, they return to the rocket. Along the way they hear a happier version of the Mysterious Sound. The others josh Alyosha’s belief that this is a woman. “Tomorrow we’ll catch her!” Vershinin japes to general hooting. Arriving, they transfer their samples to the ship, including “the most valuable, the plates and micro samples.” Again, you’d think they’d grab a space lizard or something, but perhaps I don’t get the priorities of scientific mind.

With the film nearing its end, it’s now time to deal with the purportedly suspenseful issue of whether Masha, riven by worry and women’s intuition, has opted to disobey orders and leave orbit to look for the men. Vershinin is called for and bid to hurry inside the rocket. Soon he hears a recording of the earlier transmission from their distaff colleague.

“The instructions require that I remain in orbit,” she explains, “that I wait in idleness while my friends may be in mortal danger, and perhaps need coffee poured for them.” (Actually, I may have mistranslated that last part.) “I’m violating the instructions. I am landing on Venus.” Chicks. Am I right, gentlemen?

Needless to say, her fellows are aghast. “How could she?” one asks. “She didn’t think,” another replies. “A robot can think, not a woman,” Kerns suggests. (!!) “May God forgive me,” he says, which he can because he’s not a Soviet. What exactly he wishes forgiveness for remains vague, however. Perhaps he’s admitting it’s their fault for leaving a girl in charge of their escape vehicle.

Moreover, they can’t find the Vega on radar. This suggests that perhaps something went wrong during the ship’s entry into the atmosphere and it’s been lost. If that’s true, the men are stuck on Venus for a good long while. Not only was the Vega their only chance to leave the planet before another expedition is mounted, but it also represented what is at present their only means of communicating with Earth.

As such, Vershinin suggests they split up, with some of the men taking the Sirius back up into orbit. There it can scan for the Vega and also radio Earth and have them send along the Arcturus. As they discuss this, however, they are threatened by a flash flood caused by the rainstorm currently raging outside. Heading out to investigate, somebody declares, “The bluff [on which the Sirius rests] is going under!” Good landing site, you mooks.

With the ground splitting beneath their ship, they hurry to take off before it’s too late. First they lower and abandon as much gear as they can, to make up for the extra crewmen. Meanwhile (I don’t know how he noticed this during the crisis) Vershinin has discovered that the

Vega appeared in a scan up in orbit after Masha had sent them the message, suggesting that she changed her mind again. This, of course, would be her prerogative.

Indeed, the Vega is now passing their position up in orbit and they can contact her. Masha explains that she did, in fact, realize she was making a mistake. However, the brief moment she had the engine turned on changed the Vega‘s orbit a bit, explaining why the ship didn’t show up where they expected it to be. She sends them her new coordinates, and Vershinin calls in the others so as to ready for take-off.

Performing one last task before getting on board, Alyosha is forced to use one of his rock samples as a bludgeon. To his amazement, a part of the rock shatters and reveals a carven image of a clearly human-looking visage. His daydreams about humanoid Venusians are confirmed. Caught up in his excitement, Alyosha screams that they can’t leave now, but he’s hauled up into the ship by his mates and they blast off. Seconds after the launch (big surprise) the bluff collapses.

Down below the camera cuts to a pool of water, and we hear the keening wail again. In the shimmering surface of the water, we see an image of an obviously woman-like figure. And on that artistic note, we basically end the movie.

There is another short if jaunty tune that plays over a shot of a star field, and handily it has been translated:

“Planet of Storms, till we meet again.

Our ships will return to you.

For we are the sons of the Earth!”

AFTERWORD:

Hmm, well, cultural differences aside, that was pretty standard fare. Let’s see.

Meteor Strike? Check

Giant Carnivorous Plant? Check

“Weightless” scene? Check

Astronauts armed with pistols? Check

Odd analogues to Earth dinosaurs? Check

Complete misrepresentation of other worldly conditions? Check

Ability to breathe alien atmosphere? Check (limited, but somewhat breathable)

Volcanic eruption? Check

Last minute attempt to launch rocket, with concurrent dumping of gear to lighten the load? Check

Humanoid aliens found on planet? Check

Emergency rocket launch at the last possible second? Check

Ancient alien civilization destroyed by atomic warfare? First part yes, second part no.

Planeta Bur was directed by Pavel Klushantsev, a Soviet engineer turned filmmaker who specialized in Russian sci-fi movies. Sadly, it’s hard to dig up much data on him. There is a European television documentary about him entitled The Star Dreamer (2002), but it doesn’t appear to be commercially available in this country. Although sparse, his entire filmography seems space-related, consisting of a mix of documentaries and sci-fi or combinations of the two, which often entail Soviets being the first to land upon some heavenly body.

1947 saw Meteors, 1951 Kosmos, 1958 Road to the Stars and 1962 Planeta Bur. Klushantsev also made a film apparently about a Russian moon landing called The Moon in 1965. However, this appears to have been pulled from circulation, for obvious reasons, once American astronauts landed there in 1969. Klushantsev’s final film was Mars, released in 1968. Klushantsev used his engineering skills in his film work, designing most of the ‘space’ technologies seen in them. This includes the impressively elaborate Robot John costume featured here.

These were obviously ambitious pictures for the Russian film industry, which was overseen by, and answerable to, agents of the State. Presumably the propaganda advantages of movies about Soviet space exploration were what allowed Klushantsev the freedom to make his pictures. Many genres of crowd-pleasing films were officially frowned upon in the Eastern block despite their popularity with audiences. This topic was explored in the fascinating 1997 documentary East Side Story, which covered Soviet and East German musicals. The latter was out on DVD, but seems sadly to be out of print. Netflix still carries it, though.

Indeed, it seems that once the Soviet space program was outstripped by ours, the State tossed Klushantsev aside. He died blind and in poverty in 1999. The Star Dreamer reportedly spends a good deal of time on the director’s problems with the authorities, to the point that a reviewer at Variety opined that the film “over-sells” (!!) that angle. Somehow I doubt many would think that the case. I moreover doubt said reviewer would say the same regarding a film about one of the Hollywood Ten, despite the patently more dramatic consequences of falling afoul of, or merely out of favor with, the Soviet government.

The copy of Planeta Bur I was able to track down was a typically fuzzy gray market copy, presumably duped off a 16mm print. The color is almost completely washed out, to the extent that only the occasional dull red reminded me that the picture was originally in color. In any case, it’s quite possible that the film looked gorgeous when properly printed.

Meanwhile, companies like Alpha have released budget DVDs of Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet and Women of the Prehistoric Planet. This would indicate either that these films are in the public domain, or that the rights to them could be had pretty cheaply. Perhaps one day some enterprising company will release a set featuring solid presentations of Planeta Bur and Corman’s two knock-offs, perhaps joined with The Star Dreamer or some other documentary on this obviously fascinating and neglected filmmaker. It would certainly make a great package.

Postscript: Friend of Jabootu Carl Fink provides some cogent notes.

On Russian Etymology: “Alyosha is a diminutive of Aleksei. It’s plausible that the youngest person is Alyosha because this was also true in The Brothers Karamazov.”

Carl raises a point I meant to address, but forgot, regarding a character’s statement that spacefaring ships remain vulnerable to “big meteorites.”: “Meteorites are those remnants of meteoroids which penetrate the atmosphere and land on the Earth (or in this case, Venus). While they’re in space, they are meteoroids. The fiery trail in the atmosphere is a meteor.”

Carl shares my doubts about Venusian malaria: “WTF are mosquitoes of the genus Anopheles doing on Venus?“, but negates my skepticism on the idea on one aspect of the disease: “There are several forms of malaria, and one form does indeed come and go.”

He also shares my hesitation to buy into the film’s presentation of Darwinism, expounding thusly: “It is a common misconception about evolution that it’s deterministic, and would follow the same course on any planet. As a younger world, Venus is millions of years “behind” and still in the dinosaur era. By that logic, Roman is totally correct. Logically flawless but built on a false premise.”

On dinosaur biology: “What makes you think brachiosaurs had primitive nervous systems? Hell, slugs react faster than what you’re describing. This is as scientifically silly as finding Earth dinosaurs on Venus.” Well, I learned everything I’ve ever needed to learn about dinosaurs, and all I will ever need to know, from the motion picture The Land that Time Forget. Also U-Boats. So there.

On the Bubble Car Crew ferrying the thing around by hand: “Almost exactly the same gravity as Earth’s. If I were building a car to carry to and land on Venus, I’d make it out of superlight materials. Maybe the Sovs are that smart, too?” Well, lunar craft had a pretty stripped-down look, and this think looks much like a regular car (roughly). Apparently superlight materials had come a long way in this universe.

On atmospheric: “Fire? [Regarding the camp fire in the beach scene.] Didn’t they just say there isn’t oxygen? Anyway, without the oxygen, what are all these animals breathing?”

Thanks, Carl!

Done here? Move on to the review for Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet.