Following the comparative success of The Lost Skeleton of Cadavra, which surprisingly got an actual theatrical release, we’ve seen a slew of new, ultra low-budget genre movies making fun of, well, old, ultra low-budget genre movies. And why not? If you don’t have money, it doesn’t hurt to make a film where a lack of funds is actually partly what the movie is about.

Destination Mars* is probably the one I enjoyed the most, while The Monster of Phantom Lake (another Gill Man movie, of a sorts) was perhaps the pokiest. Stomp! Shout! Scream!, a Bigfoot/girl band nostalgia piece, is probably the most accomplished. Sadly, the latter is the only one of the bunch not currently available on DVD.

[*That does remind me, I should probably check out Monarch of the Moon, made by the same guys. That and Destination Mars are actually available in a nicely-priced two-pack, currently sitting on my shelf with hundreds of its fellow unwatched brethren.]

These are films made by fans, for fans. They can be a bit cloying at times, and generally lack a professional sheen. (Although, again, that can be seen as part of the joke.) However, seldom does an unwarrented sense of superiority rear its head. They are made by people who love these movies, for people who love these movies. For no other reason than that, you should probably give them a look, or actually spend a couple of bucks and subsidize these efforts by actually buying the ones out on disc. I can think of worse ways to support the arts.

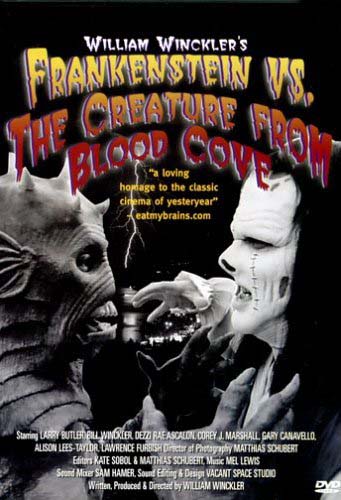

Unlike Destination Mars, which is specifically a parody of a cheapie ’50s alien invasion movie, William Winckler’s Frankenstein vs. the Creature of Blood Cove is set in a world that conflates all B-movies. Indeed, it almost seems like a pilot for a TV series set in a universe in which B-movie mad science, nuclear and environmentally-triggered gigantism (referenced in a throwaway line that’s among the film’s funniest) and the supernatural are all real.

The presence of the Frankenstein Monster (although the Monster portrayed here is more akin to Shelly’s than Universal’s) and particularly the use of melodies from the ballet “Swan Lake,” similarly employed as theme music for some of the early Universal movies such as The Mummy (1932), harken back to the glory days of the monster movie.

However, the film is set in the present day, and borrows more from monster and horror movies made in the decades since the Universals. The titular Creature of Blood Cove is not so much a redo of the Creature of the Black Lagoon, as the later, far cheesier and more violent knock-off gill-man monsters who menaced curvaceous bikini girls in films like The Horror of Party Beach, Beach Girls and the Monster and Humanoids from the Deep.

Indications of 1970s influences include some (brief) nudity and somewhat gory violence, which may prove jarring to those thinking the film is intending to only reference earlier, more innocent B-movies. However, while the 1930s-’60s are the primary focus here, there are nods to the decades since.

Notably, although filmed in black & white (which made me wish more movies were), and primarily set in the sort of generic beachfront house that keeps things from being to anchored to any one specific time period, there are indications that the film is indeed set in the present day. These include footage of modern cars, and more pertinently the rationales of the film’s chief mad scientist, Dr. Monroe Lazaroff.

Like many of his peers, Lazaroff’s literally monstrous work is motivated by incongruously benign motives. However, whereas past scientists have sought to feed the world’s poor (1955’s Tarantula) or safeguard Man’s existence in an ecologically ravished future (1973’s SSSSSS), Lazaroff himself seeks to avenge his brother’s death at the hands of terrorists by creating counter-terror monsters. “In a War on Terror,” he insists, “the ultimate terror wins.” As with many of his kind, he regrets in a pro forma way the carnage resulting from his experiments, but always with a shrug and a ‘making omelets’ sort of response.

Using typically goofy mad scientist logic, Lazaroff has whipped up a gill-man monster. Such a beast, needless to say, which would seem less than perfectly designed to track, say, Islamic terrorists in their desert strongholds. In any case, the Creature is featured in the film’s opening scene, in which it has just escaped from his creator’s obligatory basement laboratory.

As Lazaroff and his Igor-like assistant Salisbury chase the beast, the former shouts, “We’ll never catch him if he makes it to the water!” To which, as a B-movie buff, I could only nod in agreement. Sure enough, we soon see why you shouldn’t make yourself a gill-man if your house is situated next to the ocean.

The Creature—as opposed to the Monster; Frankenstein’s, this is—was apparently created via a chemical formulated by none other than the original Dr. Frankenstein. Lazaroff and his aides, Salisbury and fellow scientist Ula Foranti (who like many of her cinematic antecedents proves that a British accent makes the most ridiculous scientific malarkey sound more reasonable), therefore travel to Transylvania, where they hope to procure the hidden body of the original Frankenstein Monster. Again, the logic they use to formulate this stratagem is pretty dubious, but that’s in keeping with things, after all.

Quickly locating the body through a convenient hand-held gadget, they dig the Monster up. Along the way, though, they briefly encounter yet another monster. This incident serves not only to, well, provide another monster for us to thrill to, but to establish that the supernatural exists in this world alongside the super-scientific. Since a ghost will later play a pretty important role in things, it’s a savvy piece of scripting.

As well, I liked the fact that although frightened by such things, Ula in particularly appears patently fascinated by these occurrences. So a scientist might well be, especially the sort who make it their job to create and resurrect monsters. Lazaroff, for his part, accepts their reality but seems annoyed that such things would intrude upon his orderly, if insane, ‘scientific’ universe.

From here we meet another set of characters. These include a photographer played by scripter/director/producer Winckler (you can’t really argue with his possessive credit) and his workmates. One of these is very broadly-sketched gay guy, a character that will annoy and/or offend some, but is in keeping with the genre. This group is sent to Blood Cove to photograph some models for a skin magazine. (This also allows for background gag references to Winckler’s earlier film, The Double D Avenger). They end up being attacked by the Creature. Fleeing, they end up seeking protection at Lazaroff’s nearby house, thus tying everything together.

Lazaroff, meanwhile, is using Frankenstein’s chemicals to try to control the Monster, as he had previously attempted to do with the Creature. Neither project is at all successful, as you’d expect. After all, it’s not like Frankenstein himself ever got control of the Monster. (These chemicals of Frankenstein’s don’t originate in either the novel or the old Universals, but are in keeping with the sort of nonsense that B-movie scripters often come up with.)

I don’t want to go into things much more than that, because why ruin the film for people? In sum, the direction is more than adequate; the acting is pretty good for the kind of production this is; the monster suits are very good, although fittingly not quite so good that they’d look out of place in a regular low-budget b-movie. For instance, the gap between the elaborate Creature headpiece and the body suit is evident throughout, and that’s entirely fitting.

I was especially impressed, however, that the Creature and the Monster are both seen underwater, since that’s a whole lot more stress to put on the suits. Meanwhile, I probably laughed the loudest at Lazaroff’s typically chintzy basement lab, which includes a monster slab noticeably constructed from an old lawn chair (!).

In a nod to the 1980s, meanwhile, there are gag cameos by such luminaries as Star Trek scribe David Gerrold, Raven De La Croix, Butch “Eddie Munster” Patrick, Troma’s Lloyd Kaufman and Ron Jeremy (!). Perhaps most impressive, however, are several nice scripting touches. These are not outright gags, so much, as attitudes and character moments that are nice nods to genre conventions. Again, I could mention a couple of my favorites, but why spoil them for future viewers?

Basically, this is a well-made, affectionate and knowing valentine to old monster movies, made by fans of old monster movies for other fans of old monster movies. I fall rather squarely into that demographic, and I had a pretty good time watching the movie. I expect others will too. In any case, I certainly hope Winckler makes enough off this one to finance his next movie. (Although it’s been a couple of years since this one came out, and his website has no mention of another project.)

Aside from the movie itself, Mr. Winckler has provided something else fans enjoy; to wit, a DVD loaded with extras. He himself provides the de rigueur audio commentary; there’s an appropriately old-fashioned trailer (A SINISTER PLAN IS UNDERWAY IN A LABORATORY OF HORROR… we are informed); deleted scenes (featuring a character subplot that seems very weird, which is probably why it was dropped); 20 minutes of acting auditions; a very short and perfunctory selection of the obligatory bloopers; and a couple of in-depth documentaries, one the standard ‘making of,’ the other on the film’s music. Finally, there’s a gag segment of the Monster getting a lap dance (!) from one of the girls seen in the movie’s strip club scene.

Not all of these are essential, but Winckler has the right idea. Better to throw in everything and let the viewer decide what, if anything, he wants to waste his time with. I’m not that interested in the film’s music, for example (not to say anything derogatory about a pretty fun score), but I’m sure others would be.

The half hour ‘making of’ documentary begins by introducing us to Winckler and various members of the cast and crew. I learned, for instance, that the leading lady (who plays his character’s assistant) is Winckler’s wife, and really, you’ve got to like that sort of family filmmaking. As well, the actor playing Salisbury turns out to have done the special effects and prosthetics, to boot. This leads into the sections of the documentary that I was most interested in, which covered the making of the monster suits and make-up. The monster appliances looked even better in color, by the way.

Anyway, the disc is pretty lush, and if I had any complaint, it’s that you should always provide subtitles when there’s a commentary track. Even when you’ve seen the movie, it never hurts to have the dialogue flashing on the screen as you listen to the commentary. Still, that’s pretty small beer.

The commentary features Winckler and his director of photography Matthias Schubert. This works well, and is often the case, having two or more people keeps the comments flowing, thus sparing us from the sort of auditory dead spaces that are the bane of commentary buffs. Some of the info provided is redundant to those who (as I did) watch the other special features, but it’s pretty good nonetheless, and gives a nice insight into the making of a low-budget film.

William Winckler’s Frankenstein vs. the Creature of Blood Cove is currently exclusively available (as far as I know) via Amazon.com for $13. Netflix also carries it, both on disc and as part of their new “Instant Watching” program. Basically you can download it and watch it on your computer.