Roger Corman has been, for nearly six decades now, a successful filmmaker. Indeed, he is by almost universal acclamation the greatest B-movie filmmaker ever. My belief is that Corman achieved this distinction because he has been a capitalist first and an artist second. Hell, even his autobiography was entitled “How I Made a 100 Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime.” Note the emphasis, even in the title, of the financial end of things.

A nearly 30 year-old Corman self-started as an independent producer in 1954. Within a year he also began to direct. He assumed the latter job for the “creative challenge,” he has said. Even so, the move also clearly allowed him to exert greater financial control over his productions, and to save another salary in the process. That he grew artistically in the sixteen years he worked as a director is undeniable. Even so, he eventually hit a plateau, and at the peak of his directorial career decided to return his focus to producing. He works as such today, decades since he (more or less) hung up his directorial hat.

Despite this, Corman is still primarily thought of as a director. Partly this is because we tend to think of directors as being more important than producers. Partly it’s because Corman was so prolific a helmer; between his first film, 1955’s Five Guns West, and 1971’s Von Richthofen and Brown, Corman directed a gobsmacking 53 films. In sixteen years! And 1970-’71 only accounted for three of them. In 1957, in contrast, Corman directed nine movies.

Despite this machine-like pace, and the man’s legendary parsimony, nearly all his pictures remain at least entertaining. Moreover, several are (especially in contrast to the work of Corman’s skid row competition) quite good: It Conquered the World, Not of This Earth, A Bucket of Blood, his numerous Poe movies with Vincent Price, and X The Man With the X-Ray Eyes. Others also have their champions. And even the crappiest of his films, such as The Saga of the Viking Women, feature at least a sly sense of humor that leavens their manifest inadequacies.

In the end, Corman’s credo always seemed to be, “I will do anything to make a good movie, short of spending another dollar.” This restriction naturally included extending a film’s shooting schedule, as in the movie business time truly is money.

Yet even with his already puny budgets and schedules, Corman was known for striving to save the odd additional dollar or trimming an already short shoot. A few of his most famous movies (if only because of still heavy TV play on public access channels), The Terror and Little Shop of Horrors, were quite nearly ‘free’ movies because of the circumstances under which he made them.

Little Shop of Horrors was shot for an insanely paltry $30,000 in literally two days. The motivation for this feat was that Corman had a crack at some standing sets, which were scheduled to be torn down following the upcoming weekend. Not one to let such an opportunity go to waste, Corman corralled his chief scripting henchman Charles B. Griffith to whip out a script posthaste. 48 hours after shooting commenced, they had the bulk of the movie (everything save exterior scenes) in the can.

Astoundingly, the result is actually a pretty good film, arguably one of Corman’s best. Although uneven, it’s Borsht Belt humor holds up surprisingly well today, as does the film’s still quite funny parody of Dragnet’s then popular “just the facts” style of police drama.

Meanwhile, the plight of the nebbish hero who falls under the spell of a talking, ever more demanding man-eating plant proved sturdy enough to provide a scaffold for a successful off-Broadway musical version of the story. This, in turn, was eventually made into its own marvelous film, one which sported a $25 million budget that easily exceeded that of the fifty-plus pictures Corman directed put together.

Similarly, Corman (wearing his producer hat) had hired the aged Boris Karloff to star in Peter Bogdanovich’s brilliant thriller Targets. When the shooting of the latter wrapped, Karloff still had a few days on his contract. Corman clearly wasn’t one to let the veteran thespian off the hook. Following in the footsteps of Ed Wood Jr., Corman quickly shot some scenes of Karloff on an exaggeratedly gothic castle set; the latter being itself left over from AIP’s The Haunted Palace, starring Vincent Price.

Corman figured he’d shoot some additional stuff later to pad out this footage, and so he did. Additional scenes were was also shot by Monte Hellman, Jack Hill, and even the potential film’s other star, the young Jack Nicholson. (Nicholson played, of course, a Napoleon-era French soldier, just as you think of him.)

Predictably, the cobbled-together result proved a cinematic Mulligan’s stew. Much like Wood’s Plan 9 from Outer Space, the final film was jury rigged ex post facto around Corman’s pre-existing footage. Even so, the movie remains, flaws and all, oddly watchable, albeit largely due to the cast of Karloff, Nicholson and, inevitably, Dick Miller. In a nice grace note, the far superior Targets itself featured scenes from The Terror to represent the final gothic horror film of Byron Orlok, the somewhat autobiographical character Karloff played in that film.

Corman became a more capable director as he went along, and his films more polished as his budgets (comparatively) rose. This was especially true when he made the pictures that cemented his reputation as a surprisingly decent, and occasionally even vivid, director. These were the AIP Poe films, generally scripted by Richard Matheson, and generally starring Vincent Price.

These indeed sported larger budgets than Corman had previously enjoyed, although (surprise!) the rationale for this was purely financial. By the ‘60s, audiences weren’t supporting cheapie black and white drive double features as consistently. As well, industry and union rules were changing. One such change was that, starting in 1960, producers had to start additionally compensating actors when films were re-released to theaters or sold to television. This changed the financial picture radically.*

[*This is another reason Corman whipped out Little Shop of Horrors as he did; it was made right on the cusp of that rule change.]

Both Corman’s artistic and financial success as a filmmaker can be laid to two things. The first was a key facility, the second a key insight. The facility was Corman’s almost preternatural ability to spot genuine talent. This trait he manifested from the very beginning of his career, when his profits were centrally predicated upon sticking to ludicrously minute budgets. To accomplish this, Corman needed to able to find people who could learn their lines, or handle their equipment, and get film in the can without a lot (or any) reshoots or rehearsal time.

Corman also needed people who weren’t going to complain about extra duties. Corman from his very earliest film lugged equipment around himself; he was, in the most literal sense, a hands-on producer. Being able to deliver your lines first time out was one thing. Being able to do so while also being willing to hoist a boom mike or schlep around klieg lights or drive other cast members to the set in your car made you all the more valuable.

Corman worked like a dog, and surrounded himself with people willing to do the same. That’s why he built his famous stock company of people like Beverly Garland and Dick Miller and Jonathon Haze and Charles Griffith. They were fast, dependable and busted their asses. Once Corman found a person like that, he grabbed hold of them. And for whatever reason (mostly, one assumes, because Corman kept them working), they stuck with him in turn, sometimes for years or even decades.

Of secondary importance, perhaps, they were also good at their actual jobs, like acting or writing. If Corman’s key skill—his genius, really—was to cull the best people from the talent pool available to him, his key insight was that hoards of people were positively desperate to be in the movie business. Corman had his pick of a multitude of wannabes, and used this to his advantage.

Other producers might have used this situation for casting couch purposes; Corman did it to find virtual slave laborers. Yet his eye shows; Corman might not have Oscar-caliber performances in many of his pictures, but neither does he offer the sort of stilted non-actors you often got in films by other skid row producers. And the writers he employed tended to be a bit more literate and sly than those used by his drive-in fodder competitors. Finally, as a producer he gave opportunities to several youngsters who subsequently became some of Hollywood’s most feted and successful directors.

One reason, perhaps the central one, that so many talented filmmakers came out of Corman’s system was that it basically functioned as a boot camp. If you weren’t completely dead serious about wanting to make movies, you dropped out (or were dropped) pretty quick. If you stayed, it was because you were hungry enough to put up with anything Corman threw at you.

Needless to say, Corman exploited this situation ruthlessly. Producer Jon Davison once remarked, “If there’s a heaven, and Roger Corman has any expectation of getting there, what will open the gates for him is that he gave hundreds and hundreds of people a shot.” Note, however, that Davison adds a lot of qualifiers to Corman’s chances in this regard.

On the other hand, if he worked his people like dogs and paid them with peanuts, the fact remains that his core group stuck with him picture after picture. Partly this might have been because no matter how much of an asshole and tyrant Corman could be at times, he wasn’t asking anyone to work harder than he worked himself. (Of course, he got more money out of it, but still.)

Even so, another secret to Corman’s success was that he quite obviously actually enjoyed making movies, and did indeed want to make good ones, even if that remained a secondary goal. I once opined to Sandy Petersen that I thought director Herschell Gordon Lewis might well have become a haberdasher if he thought he could make more money at it.

I wouldn’t say the same about Corman. He made certain he made money, pretty much every single time. However, even his earliest, most threadbare work often evinced a playfulness that proved his greatest artistic strength, at least until his technical skills improved over the years.

It’s not so much that he worked in so many genres, since that only made good, financial sense. Although mostly remembered for his horror and sci-fi pictures—largely because those genres have the most fervid, maniacal fan bases—Corman from his earliest days made gangster movies, crime flicks, juvenile delinquent pictures, westerns, racing films, rock and roll movies, biker films, drug pictures, social satires, etc. Aside from servicing the market, this variety also presumably kept things fresh as he and his teams toiled like madmen to get the next movie in the can.

However, even working as he did, squeezing every single nickel until it pled for mercy, Corman’s playfulness often manifested itself. In the end, this probably gained him much of the loyalty he earned from those around him. But it wasn’t so much the variety of genres he worked in, as what he did with them. Corman might never have taken a flier with a buck, but he pushed the envelope in other fashions.

The Undead, a reincarnation / past lives horror pic, surely was initially formulated to exploit the public’s interest in Bridey Murphy, a ‘past life’ that a then real-life average American housewife supposedly revealed under hypnosis.

However, who aside from Corman and his bunch would have had the characters in the past lives flashbacks declaim their dialogue in blank verse?

Look at the evident familiarity with beatnik society, as portrayed with a satiric yet sympathetic eye in A Bucket of Blood. And what to make of 1957’s The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent? The ludicrous title alone signaled a wink to the audience. Even so, why would Corman with his skimpy budgets even try to mount a period movie about a female Viking tribe and sea serpents?

The amazing thing is, as far beyond his financial reach as this concept proved, even the latter picture stands on its own if you give it a little leeway. Corman’s audacity alone inspires enough amusement that you end up liking the picture, flaws (like the sock puppet sea monster) and all.

And really, if he could pull that one off, it’s no surprise that so few of his movies are the sort of tedious slogs so often provided by other such filmmakers. Long before anyone was attaching labels like ‘auteur’ to director’s toiling in Corman’s end of the business, surely there were some few hardcore fans who recognized how hip his work often was and actually sought out his pictures.

As time progressed, however, Corman proved successful enough that it was time to raise his game. And so when the time was right, he and AIP’s Sam Arkoff and James Nicholson decided to take a chance. Rather than give Corman his then standard $200,000 to churn out two black and white films for a double bill, they decided to use the entire sum to make one comparatively opulent film—although even then $200,000 was a pretty marginal budget—in color. The result was 1960’s The House of Usher, the movie that would secure Corman a spot as a legitimate director.

Corman didn’t entirely abandon cheapies, however. He still kicked out the occasional low budget black and white flick like 1961’s Creature from the Haunted Sea. Even so, for a goodly stretch he focused on the Poe films. And by the time those had finally run their course, so had black and white films altogether. Corman’s subsequent films were largely color contemporary dramas about bikers or gangsters (a genre he had worked in all along) or drugs.

One reason Corman grew as a filmmaker was that from the very beginning he was willing to learn from his mistakes. Of course, what he considered mistakes were generally ones of a dollar and (in his case, quite literally) cents nature. As the unofficial producer and co-director of one of his earliest films, The Beast with a Million Eyes, Corman no doubt was enraptured that the central idea of the film was of an invisible alien force that took over people and animals. What could be cheaper than invisible, after all?

So the film was quickly in the can and delivered to AIP. However, when Arkoff (as reported in his own book) screened the film for potential exhibitors, they raised Cain. They demanded a visible monster of some sort, or no sale. Arkoff handed it back to Corman, who threw probably a hundred bucks, if that, at the legendary Paul Blaisdell to toss together a monster puppet, dubbed “Little Hercules.” When this was delivered, Corman shot just enough inserts to meet the minimum monster standard requirement. By which I mean there are a few brief glimpses of the thing at the end of the picture.

From this episode Corman learned two things; first, you HAD to have a monster if you were going to sell a sci-fi film. Second, however, the monster could suck. It didn’t have to be a good monster, just a monster. Indeed, it could be downright ludicrous, and only shown for a few minutes, if that. Corman unsurprisingly took full advantage of these stipulations.

Rah, I’m a monsta!

In the years that followed, Corman specialized in horrendously cheap-looking creatures, offering comically cheapjack beasties in Creature of the Haunted Sea, Blaisdell’s beloved Beulah from It Conquered the World, the Wasp Woman and the sock puppet sea serpent from Viking Women. When he ended up with a more elaborate monster suit for Night of the Blood Beast, he naturally also re-purposed it for the same year’s Teenage Caveman.

Just as Corman was prone to allow good elements in his films as long as they didn’t cost extra money, he was also willing to let his progressive political views inform them. Most notably, Corman was a legitimately feminist director. His films might feature woman villains, but they were strong women who could hold their own against any man.

Even his female victims were less inclined to be the wilting, helpless sort; see Beverly Garland in It Conquered the World. Occasionally (and well ahead his time) women would even occupy the ‘hero’ role, as in his early Western, Gunslinger, again starring Garland. You seldom got that casual whiff of misogyny from Corman that you got from a lot of other b-movie filmmakers.

Even so, Corman learned another valuable lesson with one of his very rare films to lose money, 1962’s The Intruder. This was an anti-Klan social drama starring a young William Shatner. Such content was still controversial, and no doubt hurt the film in the South where the drive-in circuits were especially strong.

Corman’s take away, of course, was to never let a film’s politics get ahead of what the audience wanted. He was so rueful about this case that he talked about it at length in his book. Luckily, young audiences became more liberal and anti-establishment as the years passed, allowing Corman to further indulge his flavor of politics in a safely profitable fashion.

However, the political content of his films began causing clashes with the more conservative Arkoff and particularly James Nicholson over at AIP. Things came to a head after the filming of Gas-s-s-s!, a rather (to be kind) unstructured social satire Corman had made. Atypically he allowed his politics to completely get the better of him, and even he later admitted “I was truly beginning to believe I could do anything, which is why the picture ran a little out of control.”

Corman delivered the film to AIP and went to Ireland, where he began shooting an actual studio film, Von Richthofen and Brown for MGM. Corman eventually learned that AIP had re-edited Gas-s-s-s!, as they had several of his most recent films, and decided to call it quits with them. Corman describes his motives for this as being primarily about creative control, although I have my doubts. (And frankly, having seen Gas-s-s-s!, I really don’t think Corman’s cut would have been particularly less wearisome.)

I can certainly believe that Corman, now an established, veteran director, increasingly resented others tampering with his films. Even so, although Corman portrays his a split with AIP as being over directorial freedom, the fact remains that following the completion of Von Richthofen he basically hung up his director’s hat permanently. Instead, he founded New World Pictures and became, in his words, “a one-man studio.”

Half the jokes about Hollywood end with the punchline, “But what I really want to do is direct.” Therefore, Corman’s walking away from the director’s chair just when he was starting to get major studio gigs must have struck many as inexplicable. Yet in an odd way, I believe the guy who whipped out Little Shop of Horrors for thirty grand over a weekend must have somehow chaffed at the slow pace, rigid work rules and just-throw-money-at-it attitude of even a comparatively low-budget studio production.*

[*One oddity of Corman’s book is that he details at some length a fatal stunt accident that killed several people on Zeppelin, another WWI flying epic also shooting in Ireland at the same time as Von Richthofen and Brown. However, he fails to even mention that veteran stunt flyer, Charles Boddington, died in a flying accident on his own film, or that the day after that occurred there was another serious accident, albeit one that thankfully avoided further fatalities. Still, one wonders if perhaps these tragedies affected the timing of Corman’s directorial retirement.]

Whatever his true motives might have been, Corman for all his “increasingly radical” politics inevitably choose to become a suit. On the other hand, the times propitiously made his brand of politics an actual selling point. Believing in the right things was satisfying. Believing in the right things and making a buck off them at the same time, that was even better.

Moreover, the sort of young, hungry talent Corman required to make films on his minute budgets themselves craved to make ‘relevant’ films. As this also comported with the tastes of that era’s youth audience, Corman gave his employees their head. As long, of course, as they included the salable nudity and violence the audience primarily demanded, and stayed within their budgets. One obvious example was New World’s series of ‘nurse’ movies. These mixed sex and trendy politics in a commercially viable fashion. Everyone was happy.

Thus began the longest stretch of Corman’s career, one that extends to present day. Corman may have directed, officially and unofficially, over 50 films, but he’s produced quite nearly 400 of them, and continues to do so. In this role he’s gained his greatest legitimacy, having given starts to the oft noted array of major league talent: Coppola, Scorsese, James Cameron, John Sayles, Jack Nicholson, Peter Bogdanovich, Gale Anne Herd, Joe Dante, Ron Howard (as a director), Jonathon Demme, Barbara Hershey, and so and so on.

Aside from that, anyone who survives the industry long enough tends to gain some level of respectability. For Corman, the accolades have been particularly impressive. Demme gave him cameos in Philadelphia and Silence of the Lamb. Ron Howard did the same in Apollo 13.

Finally, in 2009, Corman was presented an honorary Academy Award (the same year as Gordon Willis, the cinematographer who shot films like The Godfather, and actress Lauren Bacall!). This, again, was not so much for his films, as for the talent he fostered in making them.

Presumably in order to further this cultural rehabilitation, Corman several years ago participated in a series of DVD commentaries. For these he assumed an aggressively avuncular manner of speech, as if to sell himself to his fans as lovable ol’ Uncle Rog. I’m certainly not going to deny Corman his place in film history. Still, for an essential counterpoint to Corman’s propaganda blitz, anyone interested in his career simply must listen to director Joe Dante’s loving but rueful commentary track for the original Piranha.

Dante had, like many such directors, worked his way up the ladder in Corman’s company, doing tasks like editing trailers for films like Starcrash. Eventually he and Allan Arkush decided that the best way to get a promotion was to (duh) tug at Corman’s purse strings. They bet Corman they could make a movie for a quite insanely low $25,000.

Corman naturally agreed, and the two novices crafted a film about young filmmakers like themselves. This allowed them to use a ton of stock footage of stunts and other sequences from earlier Corman-owned films, such as the (first) remake of Not of This Earth.

As usual, Corman’s eye proved out, and the two not only actually delivered a film for that sum, but a pretty good one, called Hollywood Boulevard. The DVD for that movie also has an essential Dante commentary, where he is joined by Arkush. At one point there’s a star wipe used as a scene transition. The two reveal that they used their paltry $500 directors’ fee to pay for it, since otherwise they couldn’t have afforded it.

Dante and Arkush’s gamble paid off, as did Corman’s: New World made millions off the film. And so Dante got a real assignment, a knock-off of Jaws entitled Piranha sporting an efficient script by John Sayles, featuring his usual satirical undertones. As indicated, the entire commentary for this film is one of the best I’ve ever listened to, but one anecdote is essential for the Corman buff.

As Dante tells it, Piranha was set to have an $800,000 budget. (In case that sounds like a lot after Hollywood Boulevard’s twenty-five grand, let it be noted that Jaws itself had a not entirely extravagant budget of $12 million dollars four years earlier, and that Piranha featured numerous large scale action set pieces requiring dozens, even hundreds, of extras.) The idea was that New World, aka Corman himself, would kick in half the budget, while the rest would be raised by pre-selling the foreign rights.

Literally a few days before filming was to commence on this ambitious project helmed by a young neophyte, Dante received word some devastating news. Corman had (presumably he had planned this all along) ‘suddenly’ decided, having raised the $400,000 from overseas investors, to cut the budget down to that amount. He thus would avoid putting even a nickel of his own money into the project, meaning that any American profits at all would be pure gravy.

Dante understandably fell into an utter panic. Again as he tells it, he called his producer in tears. The latter promised to speak to Corman. Following these pleas, Corman agreed to kick in at least half of what he had originally promised. This pushed the budget back up to $600,000. One must further wonder if Corman had meant to kick in the $200,000 (and only $200,000) all along, and only said he was kicking in nothing so that Dante et al would feel relieved they were getting even that much. It wouldn’t surprise me.

Either way, that story really captures what it must have been like to have worked for or with Roger Corman. On the one hand, you actually, really got to make movies. Hunger and talent meant more than age, experience and connections. Moreover, as long as you stuck to the budget and included all the elements Corman mandated, you could make the film you wanted to make, and how you wanted to make it. And in the end, the travails of working for New World must have made working on major studio pictures seem like cake. Corman provided the Nietzschean school of filmmaking: Whatever doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger.

Yet that was Roger Corman later in life. What about an earlier time….

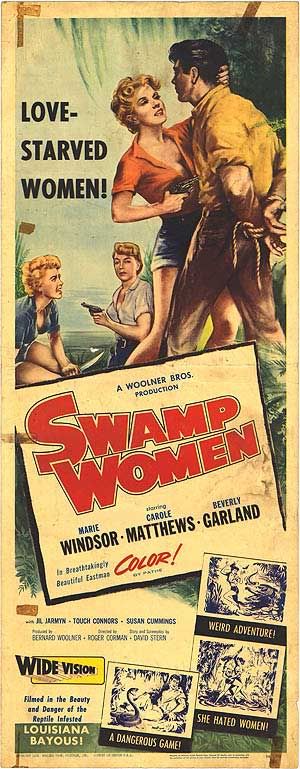

Swamp Women (1955)

For what it’s worth, I didn’t have a copy of this handy. However, it’s available in a pretty grainy streaming presentation for free on the Web. If you wish to see it for yourself, just Google the title. The downside was that I wasn’t able to grab any stills from it.

Swamp Women was, I believe, but the second film Corman helmed. It was suggested to me as a rare Corman stinker (and it was even one of the Medveds’ original 50 Worst Films of All Time), but really, I didn’t think it was that bad. Let’s give it a look.

It opens with credits appearing over a series of the odd, expressionistic paintings Corman favored in his early films. (The best are the ones for Sorority Girl, which make the upcoming movie look like a supernatural horror picture, even though it isn’t.) These images promise more sex and violence than the film delivers, but that was pretty much par for the course back in the ‘50s.

Corman’s taste for strong women is already on display, in that the film features both a tough, capable female lead and a distaff gang of escaped convicts. This latter trio will menace he-man “Touch” Connors (he would change his screen name to Mike Connors and later became famous as TV’s Mannix) and his girlfriend. Despite being a thoroughly macho male, Connors spends the bulk of the picture helplessly tied up.

Even this early, Corman was assembling his stock company. The cast features such Corman regulars as Jonathon Haze (later the star of Little Shop of Horrors), Ed Nelson and Beverly Garland. Connors himself worked for Corman on four pictures. However, he then moved on because Corman wouldn’t raise his $400 a movie salary.

Swamp Women’s lead bad girl is played by Marie Windsor, earlier the star of Cat-Women of the Moon. In an odd note, the screenplay by David Stern is the only one that didn’t star animals. Stern wrote the first two Francis the Talking Mule pictures, and wrote dialogue for Rhubarb, a comedy about a cat who inherits a baseball team. Swamp Women was his last screenplay, so he might not have enjoyed toiling the lower ends of the film industry.

We open with Bob Matthews (Connors) passionately kissing his girlfriend Marie (who, in one of the film’s few instances of bad acting, sports a comic opera Southern accent) at Mardi Gras. As you’d imagine, the setting allows for Bob to peer off-camera and gaze upon several minutes’ worth of parade and party stock footage. You’ve got to eat up those 68 minutes somehow. Then Bob mentions “some of the meanest country in the world…swampland, bayou country, jungle.” Foreshadowing alert! Marie perks up when he says he has interest in some oil wells out there, and suggests they make a field trip to look them over.

Along the way, they run into Charlie the Pickpocket (Haze), who cleans the unsuspecting Bob out. (Charlie gets caught a few minutes later, though, when he bumps into Bob a second time.) Then more stock footage. I was going to make a crack about the budget being all up there on the screen, but given what the budget probably was, it actually is. Then back to Bob and Marie, then…more stock footage. Yeesh.

Cut to the police station. As a beat cop processes Charlie, we meet Police Lt. Lee Hampton. By the way, Lee’s a girl! Soon she’s talking to her captain. Unsurprisingly, Lee’s job is to join the infamous Nardo gang in prison, and worm her way into their trust. Then she’ll manufacture an escape, with the plan being that the gang, led by Josie Nardo (Windsor) will lead her to the “Nardo diamonds,” valuable gems Nardo stole three years ago that were never recovered.

Presumably the gang will come across Bob and Marie in the swamp and take them hostage, with Lee then having to worry about protecting these civilians as well as getting back the gems and re-arresting the Nardo Gang. Also, since Marie has been shown to be a bit of a gold digger, I assume she’ll get kacked, clearing the way for a romance between Bob and Lee.

We cut to the prison to meet the three-woman gang, whose hellcat reputation is initially established by having one woman tepidly slap another prisoner. Not exactly A Clockwork Orange, but there you go. The slap comes courtesy of Vera (Garland), the gang’s staple violence-crazy one. Billie is the blonde man-crazy one, and Josie is the hard as nails leader.

So the escape is engineered, and everything is going to Lee’s plan. Then we cut to Bob and Marie patrolling the bayou, unaware of their impending Date with Destiny. Meanwhile, we skip an entire scene of the Nardo gang meeting with their outside contact. And why not, it isn’t needed. Instead, we now see the gang and Lee stranded in the swamp because of a faulty boat, but armed and clad in tight, butt-hugging jeans.

Seeing them, Bob and Marie ride to the rescue, with predictable results. First their bit player guide gets himself shot. Lee disarms Vera (the killing of a civilian has to be kind of an ‘oops’) while managing to stay in character, while Josie effortlessly pistol whips Bob. I’m not sure how the hunky, six-foot plus Connors liked getting served like that by a far more petite woman—although Windsor was no china doll—but he went with it. Still, you didn’t see a lot of scenes like that in Mannix.

As the women look over dazed Hunk o’ Man Bob, each plays their part. Kill-crazy Vera wants to shoot him (preferably after he wakes up, “so he’ll see it coming”); Billie gives him the goo-goo eyes, and Lee maneuvers to keep him and Marie alive while not tipping her real identity. She of course plays the “they’d make good hostages in an emergency” card, and since this is a movie, Josie buys it.

As predicted, we now enter the time-wasting travelogue portion of the film. The party travels along the water, pointing every once in a while to indicate some piece of stock footage. If they had cut in a stop-motion stegosaurus instead of an alligator or bird flock, this could easily turn into Journey to the Beginning of Time. This, if you’re interested, you can watch in its entirety on YouTube.

Marie continues to be all sobby and stuff, and even offers to sell out Bob at one point. This craven act prompts a disgusted Vera to memorably sneer, “I wouldn’t wear your lousy sweater if you gave it to me!” (???!!) Uhm…burn? Anyway, I assume we’re not supposed to feel too sorry when Marie gets killed later.

Vera continues to pick fights with Lee; Billie continues to vamp Bob, etc. In other words, we’ve reached the treading water portion of things. This doesn’t bode well for the next half hour, which we’ll have to get past to reach the climax. In one pivotal scene, however, the girls get tipsy and, using a Bowie knife (!), cut the legs off their jeans to fashion themselves some strangely well-tailored short-shorts. This naturally serves to increase what in the ‘50s represented the film’s sex quotient. Sadly, though, the Foster Brooks-grade ‘drunk’ acting lowers the thesping level.

On the other hand, a scene (accompanied by cool jazz on the soundtrack) where the women elaborate their plans once they sell the diamonds manages to provide several neat bits of characterization while eating up the clock. Again, it’s a bit better than you’d expect, and their goals are a tad more subtle than they could have been.

Billie’s plan in particular is interesting. She plans to get revenge on the judge and jury that sent her man to the chair, but (typically for her) via sex rather than violence. Her scheme involves changing her face via plastic surgery, then seducing them all one by one and ruining their lives by making their wives and children hate them. That Billie would be the revenge-minded one rather than Vera is kind of interesting, and her plan makes a sort of sense. And really, it suggests Vera is an out and out sociopath who doesn’t care enough about anyone else to worry about revenge. And it’s not like she really needs a reason to want to kill.

Presumably aroused by the delineation of her scheme, Billie later sneaks over to vamp Bob. This sends Vera (surprise) into a rage, and Josie has to break things up. Then she turns to Bob, who’s tied to a tree, and warns him, “Stay out of trouble, Mister!” Like it’s his fault. Josie even admits this is so before walking away.

Then Marie tries to escape, with predictable results. She falls in the water, proves (what else) helpless, and Lee leaps to her rescue. However, both women are then menaced by a rubber alligator. And if that doesn’t spell quality cinema to you, my friend, then we have little to discuss.

At his request, Josie cuts Bob free, passively lets him grab a big knife (!), and he jumps in to save them. In between some stock shots of several different ‘gators, we get to see Connors manipulate and stabs at the rubber one, in the finest tradition of Bela Lugosi and the listless rubber octopus from Bride of the Monster. Anyway, he and Lee make it back, but I guess Marie bought it somehow. Marie, we hardly knew ye.

So the gang and Bob head deeper into the swamp. Meanwhile, we cut to Lee’s boss on his office phone, pretending to direct the police efforts to surreptitiously follow after them. Back in the bayou, a bizarrely nonchalant Bob (he doesn’t exactly seem bereft regarding Marie’s death) and Lee inevitably start making the eyes at one another. I mean, they are the male and female leads, after all. In fact, he quickly starts macking on her. A true operator isn’t inhibited by having his wrists tied up, I guess. (Odder is that Lee goes along with it. Good undercover work, officer.)

Vera, apparently the gang’s designated vagina-blocker, again appears to prevent any funny business. Didn’t she see the sock Lee tied to that tree branch? What a buzz kill. Then the next day Billie and Lee go swimming. They tell Josie to watch out for ‘gators, but I mean, really? You wouldn’t get me in that water on a bet. Again, this is a ‘sex’ thing, because even if the water is too brackish to let us see anything, they’re presumably like, you know, naked and stuff. Tee hee.

Bob then ambles over to take a gander, which weirdly is protested by an irate Billie. Since when is she such a prude? Josie also finds Billie’s squawking funny, and seemingly is prepared to again untie Bob’s hands so he can also get in the water. (They’re pretty lackadaisical about keep him tied up, aren’t they?) Billie’s protests finally win the day, and an amused Bob strolls back to camp.

Anyway, further time-wasting stuff happens, including a scene ripped off from John Huston’s The African Queen. (!!) More stock and travelogue-type footage, etc. Then they finally reach the spot where the diamonds are supposed to be buried in a strongbox, under what appears to be about an inch of straw. Moreover, the entire location seems utterly generic and unmarked in any way, miles and miles into the desolate, ever-changing bayou. There’s not even a big W. Still, they got here, so there you go.

There’s still about 25 minutes of movie left, which is I’ll admit is more than I anticipated. I assume we’re going to go into Treasure of Sierra Madre mode, with the gang starting to murderously mistrust each other now that they’ve retrieved the diamonds. Hilariously, Billie does scoop up a goodly handful of them and scatters them all over the swamp, which earns her but a mild rebuke.

However, she mouths back to Vera, and we finally get the cat fight we’ve been waiting for all movie. I have to say, Garland and Jil Jarmyn, the actress playing Billie, are pretty game for the whole thing, even carrying it into the mucky waters. As usual, Corman didn’t hire anyone too prissy to do their job.

Eventually Josie goes in after them to break things up. Why Lee doesn’t take advantage of this clear opportunity to get the drop on them is left to our imaginations. After all, they’ve retrieved the diamonds now. I’d think getting them while they’re all panting awkwardly out in the water would be a good bet. The moment passes, however.

Sure enough, having the diamonds starts giving people ideas. Billie is the first to give into temptation, trying to talk Josie into bumping off Vera and Lee. Whether she then plans to kack Josie too is moot, as the latter is entirely into the whole ‘honor among thieves’ thing and refuses to engage in such a gauche scheme. Anyway, she rebuffs Billie rather forcefully.

That night, however, Vera manages to steal all of the other ladies’ revolvers as they sleep. Boy, you just can’t trust anybody anymore. If she plans to steal the diamonds, I can only assume she plans to kill the others. So if I were her, once she had Lee and Josie’s gats (as she does), I’d have just shot the slumbering Billie in the head and then gunned down the other two before they roused themselves. That would end the movie about 18 minutes early, though, so she manages to get Billie’s rod too and then hides them in a burlap sack about two feet from all her compatriots. So clearly her plan is…I have no friggin’ idea.

Ah. She runs off with the sack o’ guns and the strongbox with the diamonds. Yes, lugging a big metal box around is much easier than jamming the gems in her pocket or something. Her fatal mistake, though, is that she pauses to (maybe) plug the sleeping Bob. Because that sure wouldn’t wake the women up, being a good six feet away as they are.

However, the snoozing Bob snuggles against her, and Vera’s dormant womanly instincts are stirred. He wakes, and Vera covers his mouth and quietly offers to take him with. Really? This whole thing makes no sense. Why Vera doesn’t just kill everyone as they sleep—I’d say a gun in each hand would do the job nicely—seems entirely a matter of It’s In the Script. She has all the guns…she has the diamonds…hell, I’d be shooting everyone at this point. And even aside from the fact that bloodthirstiness has been Vera’s only assigned attribute up to now, her sudden overwhelming desire for Bob is completely out of left field.

Prodded at gunpoint, Bob precedes Vera through the woods. Cut to the next morning (!) when Billie finally awakens. Finding Vera and Bob gone, she raises the alarm. What a bunch of sleepyheads! Of course, Vera would have taken the boat, stranding the others well behind her. Right? Why, no she didn’t! Because….LOOK, A FLUFFY DOG! “Vera’s smart,” Josie muses, “and she’s clever.” Yes, not to mention intelligent and crafty and brainy and sly and artful and cunning and savvy and keen and ingenious and astute.

“The first thing we’ve got to do is find out where she’s at,” Josie continues. Hey, Vera’s apparently not the only smart and clever one. And intelligent and crafty and brainy and sly and artful and cunning and savvy and keen and ingenious and astute. So the women split up, and Lee quickly finds a broken branch. Obviously this marks Vera’s trail, because how else would a branch get broken? Such a thing could never occur in nature.

They make to follow. Josie cautions them that Vera will shoot on sight, and thus they must be quiet. They agree and immediately shove aside a large branch full of dried leaves that makes a very loud rustling sound. Wow, Natty Bumpo had nothing on these broads. Also, they are respectively wearing a bright red shirt, a bright light blue shirt and a bright yellow shirt. So, you know, they blend into the swampland perfectly, like ninjas.

They almost immediately—although I assume it’s meant to be at least some time later—manage to spot Bob, and then Vera, who’s up in a tree with a gun and apparently waiting to mow them down. (Actress Beverly Garland, playing Vera, is seated in such a way as to exploit her shapely gams to maximum effect.)

Good grief, if Vera were that set on shooting them, why didn’t she do it when they are asleep and she had all the guns and they were completely helpless? (Hint: Because then they would all be dead.) As Vera waits up in her smart and clever and intelligent and crafty and brainy and sly and artful and cunning and savvy and keen and ingenious and astute trap, she and Bob yell back and forth to each other. Man, everyone’s a ninja in this thing.

“How’d she ever get up in that tree?” an astounded Billie wonders. Yep, that’s a mystery, all right. A human, up in a tree! Who’s ever seen the like? Josie, however, points out the flaw in Vera’s plan. She probably thinks she’s safe, Josie explains, because she knows they don’t have guns. “So if we could shoot her, the surprise would be on our side!” Well, I can’t argue with that logic.

Josie’s plan is to awkwardly tie her hunting knife to the end of a long thin stick and thus create an optimally weighted throwing spear. Then she’ll run into the clearing, hurl this aerodynamically perfect weapon twenty feet up in air and fatally impale her foe. (I guess it would be petty of me to point out that, technically, this wouldn’t amount to “shooting” her.) Josie knows she can do it because she “got a couple of rats with [such a spear] once” when she was a kid. A couple of rats, no doubt, who were dead shots and warily sequestered up in a tree with four handguns.

Of course, her plan requires Vera to be distracted. “Get her to take a shot at you,” Josie instructs her compatriots, “but don’t do it so good you get yourself killed.”(I guess it would be petty of me to point out that less than two minutes ago Josie warned “Vera can hit anything she can see.”) So instructed, the women head out.

So Lee distracts Vera initially by jumping out and yelling, “Hey, Vera!” Very sly, our Lee. Vera proves less able a shot than advertised, maybe because she doesn’t seem to aim when she fires. Also, she oddly shoots straight ahead, although she is up in a tree and thus should, one would suppose, find firing down at the ground a more intuitive strategy.

Even better for the women, Vera’s first revolver runs out of bullets after two shots. I don’t know why killers in B-movies so often carry pistols with only one or two bullets in them, but they do. Maybe they’re only issued that many cartridges, like Barney Fife, or maybe they feel they can move their guns around faster if they’re not weighted down with all that additional ammunition.

Then Billie appears on the other side of Vera, and draws quite literally aimless fire by yelling, “Hey, Vera! It’s Billie!” Vera is patently firing blind, suggesting perhaps that she’s not quite as smart and clever and so on as advertised. First, for firing at something she can’t see and wasting precious ammunition, and second for not choosing a vantage point that would allow her to better spy her prey when they approached. I mean, I kind of figured that was the whole nexus of her plan.

Oh, and then there’s the whole thing where she could have just shot all the others when they were sleeping and helpless, or stolen the boat and been miles downriver by now. Aside from all that, though, her scheme is perfect. And to be fair to her, it’s not like Lee and Billie’s bright red and orange shirts would make them easy to see or anything.

So Vera continues to waste bullets like they’re water—albeit water from a dessert canteen that was only a third filled to start with. Plus, her second gun has three bullets in it. Too bad she doesn’t have five revolvers, since the last one might actually sport a completely filled cylinder. “Why don’t they come out?” Vera carps, all while continue to send stray bullets into the brush. Yeah, it’s a mystery, all right.*

[*Maybe Vera’s a Cubs fan. Over the years, you become inured to the idea that Cubs batters on two outs will invariably swing at the first pitch from a conspicuously wild pitcher who’s just walked the previous three players, popping the ball up in the air and killing a potentially game-saving rally. Thus we’re always surprised when hitters on other teams for some reason choose to forgo this strategy, and force a Cubs pitcher in similar straits to instead walk in runs. “Why don’t they swing?” one can hear a frustrated Vera ask in the latter situation.]

It should be noted that Bob, sitting on the ground and tied in one position, quite obviously sees the woman as they run around. Again, you’d think Vera being up in the air would have a superior vantage, but I guess not. Finally, a bored Mother Nature decides to move things along, and sends a rattle snake on a string to menace the hapless Bob.

At this point Josie suddenly is somehow positioned right under Vera, and lets fly with her swampmade spear. Needless to say, her aim is true. However, the strike isn’t immediately fatal, and Vera has time for a last shot. With this, the woman who couldn’t hit any of the three full-sized adults popping up and down like Whack-a-Moles manages to neatly decapitate the snake.*

[*This scene features a real snake being killed, sure to turn off many modern viewers. However, if I remember this anecdote correctly, it was a real and quite dangerous wild snake that somebody on the crew shot when it appeared in their midst. Meanwhile, someone—you’d think Corman would be a good bet—decided the snake represented found art and had grabbed a camera and was filming it when this happened.]

Vera dies, but is redeemed in that her last act was one of love rather than vengeance. The others muse on this. “She always was a good shot,” Billie admits. Yeah, if the others had been snakes instead of grown women in gaudily-colored shirts they would have been screwed.

Cut to the survivors setting off in the boat. Sure, take the easy way out of the swamp. Yes, Vera’s dead, but I consider her avoidance of the craft to be a moral victory for her sense of rugged, pioneer spirit.

They later stop to make camp for the night, whereupon we again see that nobody has a problem with Billie shifting the diamonds through her hands in a Scrooge McDuck-like fashion. Sure, she might lose one or two or a dozen of them in the process. But hell, they’re only the diamonds they’ve waited three years and risked their lives to reclaim.

With the film about to wrap up (and probably give Bob a moment of last minute heroics), Lee starts acting suspicious, and drawing Josie’s attention. Perhaps to see how Lee will react, Josie starts talking about how they’ll have to kill Bob. Because if that was her plan, it makes total sense that they’d lug him all through the swamp, tied up and slowing them down the entire trip, and then kack him right at the end when tons of cops would presumably be drawing a net about their position.

Lee does protest, and the fact that she’s not murder-crazy like all good crooks increases Josie’s suspicions. Since Lee argues that the sound of a shot might bring the cops down on them, Josie hands her a knife. Oh, yeah, that’s right. You can kill people without shooting them. Anyway, Josie makes it clear that Lee better prove herself right quick. Moreover, Josie demands that Lee hand her gun over before getting the knife.

Lee doesn’t like this plan, and the two start tussling. Billie prepares to shoot Lee, allowing for a bit of last-minute heroics by Bob (didn’t see that coming). He suddenly appears in frame and kicks the gun from her hands. He then manages to keep the much smaller woman pinned to a tree, hands tied or not. This is clearly silly, as we have now all learned from modern action films and TV shows that 100 pound women can toss hulking men around like tenpins. However, they apparently didn’t know any better in the 1950s.

Things look bad for Lee, who loses her gun while Josie still has her knife. However, Our Heroine disarms her foe and the two continue to grapple in a not very convincing style. This is ironic, really, since their slow awkward movements more greatly resemble a real life brawl than the sort of explosive, tightly choreographed mayhem we’ve been trained to expect.

In the end, Good triumphs and Evil is easily rendered unconscious. Then Lee and Bob enter into the obligatory end-of-picture clinch, at least to the extent that they can with Bob’s hands yet tied. Finding this unsatisfactory, Lee frees him and the smoothing commences, no doubt to the extreme, facial-distorting disgust of the kiddie matinee crowd.

The film concludes with Bob promising to stand by Lee, still unaware that she’s a cop. If I had to guess, I’d say their romance dies when he learns that their relationship will entail more than just showing up for the occasional conjugal visit. And fade out on one of Roger Corman’s earliest efforts.

Even this early in his nascent career, Corman’s product is at the very least workmanlike. He knows how to place a camera, and his actors are capable across the board. Save for an occasional bit of authorized scenery-chewing by Garland (and Marie’s atrocious Southern accent), nearly the entire cast, even the bit players, underplays things quite credibly. The story advances quickly, and hits all its marks along the way. True, a couple of the situations near the end are pretty silly, but then logic was never the mark of the B-movie.

The lack of budget certainly shows now and again, although that would have been par for the course for this sort of picture. And while nothing here is going to set the world on fire, it remains professional product all the way through. Many directors working at Corman’s lowly budget level would never make a film this competent; in other cases, it would represent their best work. For Corman, it was the bottom rung of his career ladder.

And, yes, the alligator fight is pretty fakey. Even so, kiddie audiences would have been familiar with such things from the bargain basement jungle epics Hollywood was still putting out. They either would have just gone with it, or used it as an opportunity for community jeering and tossing popcorn at the screen. Which, pretty much, is what I did with it.

Still, it says something that when I fielded suggestions for a bad Corman movie from my eminently learned colleagues, this was one of the only titles they proffered. That this represents Corman’s nadir as a director speaks volumes about why he eventually garnered the fairly exalted reputation he did. Again, I don’t want to oversell this movie. It’s a crudely fashioned, cheap little flick. However, I’ve seen worse…a lot worse. And by people with a lot more resources and experience at their disposal than Corman had here.

Skimpiest Box Movie Poster ever!

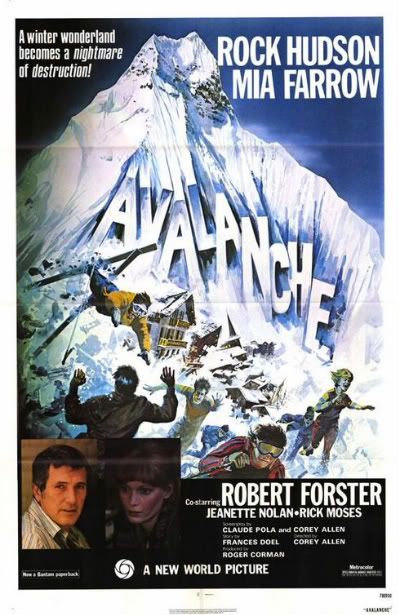

Avalanche (1978)

Reviewing Avalanche as a movie is kind of beside the point. Despite being (ahem) one of New World’s bigger budgeted films, the picture receives but a single paragraph in Corman’s book, as published in 1990: “I remember Julie [Corman’s wife] and I were at a Colorado ski resort to begin shooting on a disaster film called Avalanche with Rock Hudson and Mia Farrow. By the time cameras rolled we had presold all the rights for $1.8 million, considerably more [I’ll bet!] than the film’s negative cost. So at the end of the day, Julie and I broke out a bottle of champagne. I had faith in the director and the production manager. All we had to do was finish the picture and our profit was locked in.”

Ah, the romance of show business.

Knowing Corman, if he presold the rights for $1.8 million, he plowed at most half of that figure into making the film. It shows; to the extent the film resembles the work of Irwin “The Master of Disaster” Allen, it’s less Towering Inferno or even The Swarm, and much more Fire or Flood, the twin TV disaster flicks Allen made for network television broadcast.

Indeed, you could argue those films had better casts, or at least disaster movie casts. Corman blew his limited wad on two names, Rock Hudson and Mia Farrow. And neither, unsurprisingly, was really a big star at this point. Hudson by the ‘70s was primarily known as the lead of TV’s McMillan & Wife, which ran for much of the decade. Film-wise in the ‘70s, he starred in five theatrical movies between 1970 and ’76, none of which was a particular hit. Avalanche was his first movie in two years.

Mia Farrow was probably a bit better off, but not that much. Although a soap opera actress in the ‘60s, Farrow was then most famous as the elfin, much younger wife of Frank Sinatra. Her star rose dramatically, however, with a starring turn in 1968’s Rosemary’s Baby. After following that up with a couple of bombs, she again starred in a successful thriller, 1971’s See No Evil.

After that she wandered a career desert, however, until she got hitched with and became the perennial co-star of Woody Allen in the ’80s. During this extended dry period, she starred in one high profile flop, the 1974 version of The Great Gatsby. Otherwise between See No Evil and Avalanche, she starred in such titles as Goodbye Raggedy Ann, The Private Eye, The Haunting of Julia, The Wedding, and twice played Peter Pan on TV. So much like Hudson, she was more a ‘star’ in the sense that people knew who she was, more than being at that time especially popular.

Even so, after the two leads there was a rather dramatic drop-off even from their anemic star appeal. Familiar TV actor and later B-movie icon Robert Forster is the film’s third biggest actor. Hudson’s mom is played by Jeanette Nolan, a familiar TV face, as was character actor Steve Franklin, the sort of guy who had guest starred on nearly every single TV sitcom of the 1960s. That’s about it for even vaguely familiar faces, however. At least Flood and Fire boasted a far deeper bench of familiar TV actors to threaten or bump off.

This aspect is particularly obnoxious in a disaster film. Given that Hudson and Farrow are the traditional Estranged Couple Who Fall in Love Again in the Midst of Disaster, they pretty clearly will not get killed. This leaves Forster and then people like Nolan and Franklin as audience-pleasing sacrificial lambs, and those aren’t the sort of names people would get overly excited to see kacked.

Finally, and not to beat two catatonic horses to death here, but neither Hudson nor Farrow is a particularly high-wattage performer. Hudson is stoic, Farrow is mousy. The best word for the latter’s physical appearance here is wan. Their shared lack of, shall we say, emotional restraint works from the standpoint of them being estranged spouses who are uncomfortable in each other’s presence. From the standpoint of entertaining the audience, not so much. Neither was capable of the sort of scenery-chewing a flick like this desperately needed.

Arguably the sole moment of enjoyable over the top thesping either provides occurs early on when Hudson, hoping for a rapprochement, first greets Farrow with an awkwardly strenuous grin clearly demanded from him by the director. With skin pulled taut over his facial muscles (an effect exaggerated by the plastic surgery he’d no doubt had by then) and his pompadour, he for this brief moment comically resembles Liberace. And no, that’s not an attempt at a gay joke of some sort; he actually looked like Liberace.

And if Corman had “faith” in his director, Corey Allen, it’s because Allen’s career was basically made up of a ton of TV work. (Well, to be fair he did also direct The Erotic Adventures of Pinocchio.) This unsurprisingly meant Corman had faith Allen would get the movie finished on time and on budget, not that he would deliver a particularly good film or anything. And like Sam Arkoff before him, Corman went off the rails here—albeit in a far less spectacular fashion—because a good disaster movie just requires more funds than Corman was willing to part with. As such, for a movie released a few years after Star Wars, the effects work is downright embarrassing.

To reiterate, the film fails to provide either of the two main pleasures of the genre that had dominated the box office throughout the ‘70s: Spectacular effects and spectacular celebrity deaths. Given this, the most you can hope for is to derive some amusement from the film’s shortcomings. Luckily, in regards the film pays off, although it provides chuckles rather than being a laugh riot like The Swarm. Even the DVD is half-assed, presenting the film in a full screen presentation. The picture is so utterly generic and uninspired it’s like nobody remembered it wasn’t actually a TV movie.

Mostly the picture got made, quite obviously, because they were given the run of an actual ski resort to film in. Aside from the genuinely spectacular scenery and ski lodge product placement, however, the movie is mostly just stolid. The script is stolid, the direction’s stolid, as are the acting and even the music. Most of the risible material comes from the patently inadequate f/x work, as well as the film’s overwhelming ‘70s-ness. People are highly groovy and with it, and say things like, “Are you going to turn into a swinger?” and “I just want to be part of this whole fantastic thing going on here!” and “I can dig that, let me tell you.”

Even so, a smiling Corman would surely retort, “Yes, but that misfire made me money before it was even in the can.”

- Farrow is the first actor we see, and her first line is “I have a reservation.” To this I thought, “Yeah, well, you’re not the only one.”

- The exposition that informs us that Farrow is Hudson’s estranged spouse is clunky and…what’s the word I’m looking for…stolid. The mechanism for this is a hotel reception desk worker who asks the sorts of personal questions that would get her quickly canned in real life.

- Jeanette Nolan is playing one of those tiresome Saucy Old Women Who Always Speaks Their Minds. She is introduced loudly yelling to Farrow up a flight of stairs, much to the edification, I’m sure, of all the guests quietly eating breakfast in the immediate area.

- Steve Franklin, best known for playing hapless schnooks, here plays a hapless schnook. Odds he’ll see the end of the picture: About one in a thousand.

- Hudson is introduced via a series of shots where we see him framed in a distant window. It’s a metaphor for his emotional isolation from all he loves. Get it?

- When he spots Farrow, twenty years his junior, he nonetheless runs to her like a puppy dog. She remains distant, however, in a Mia Farrow-ish mumbly sort of way. Don’t worry, I’m sure after you save her life later on in the picture she’ll be yours again.

- Farrow meets Hudson’s personal assistant, who is clearly—and I mean clearly—carrying a torch for Hudson.

- Hudson loses control and grabs Farrow for a would-be passionate smooch. Let’s just say it doesn’t set the screen ablaze with passion. The utter lack of chemistry between the two is so tangible that their scenes together are actually uncomfortable to watch. Nor for a second do we ever believe that they were ever a couple. I’m not kidding when I say the scenes would have played better with Dack Rambo and Connie Sellica assaying the parts.

- Hudson has a purportedly big monologue about how long and hard he’s fought to bring his ski lodge dream to fruition. The idea is that when tragedy strikes on the very cusp of him finally realizing his dream, it will be extra poignant. Again, not so much.

- He also carps about the environmentalists “who say I’m destroying the environment!” Ah, he’ll be brought down by his own hubris in trying to tame Mother Nature in furtherance of zzzzzzzzz….

- Miscellaneous snow fodder include two ultra-cool pro skiers and an emotionally fragile young figure skater Facing Adversity But Committed To Pulling It All Together. The latter is around mostly to look good in legless leotards and to be the Tragic Victim of Fate. (Oops, sorry.)

- Robert Forster is a troublemaking world-famous nature photographer (really), given the Dickensian moniker of Nick Thorne. He’s inevitably the film’s obligatory Righteous Guy Who Warns of Disaster But Is Ignored. He’s concerned that Hudson is cutting down too many trees to create tourist-friendly vistas. Baring the mountain to this extent, Forster warns, increases the risk of an avalanche.

- Which, in case you forgot, is the name of the movie. So he’s probably on to something.

- Hilariously, he ‘proves’ his case by tossing a snow ball onto the mountain slope, which after a moment begins to *GASP* roll down the incline of its own accord. “That was a reaction of unstable snow to the sound waves made by that saw!” he explains, referencing a nearby work crew. Yet despite such proof they ignore him! Madness!

- With a sparse 90 minute running time, they immediately proceed to the first mini-disaster. Pro skier Bruce is practicing (in an area chockfull of trees, so whatever) when a mini-avalanche occurs. The suspense is…something, until he escapes death by jumping off a hill and high up into a tree. We here get our first taste of the film’s cheapie compositing effects.

- Oh, this all happens conveniently right by Forster’s woodland cabin, so he can see it occur.

- Also, there’s this whole really boring subplot about Hudson being in bed with a crooked politician and now there’s a scandal and his dreams could be derailed blah blah blah. Economically, this plot device plays out mostly in scenes of Hudson yelling into a phone.

- Another dream this is ruining—oh, the pathos—is Hudson’s goal of getting back together with Farrow. She obviously left him because he always ignored her in favor of the lodge, and now he’s doing it again. Only when disaster strikes will Hudson learn a valuable lesson about what is important, so at least something good will come of all his guests getting horribly killed and maimed.

- Forster confronts Hudson and his chief forester blah blah blah. We learn that Forster is wiser than everyone else because (this is always the case in disaster movies) they are all concerned with “data” and what “the book” says. Damn it, what about Forster’s gut? “I can feel it!” he implores them. Don’t they realize that’s the important thing?! This cliché is a staple in nearly every disaster film, one of the most predictably anti-science genres there is. Here they don’t even give Forster the fig leaf of being a ‘rogue’ scientist. I guess being a ‘nature photographer’ is good enough, because, like, you know, he’s all in tune with Nature and stuff. Plus, Forster had played a half-American Indian cop as TV’s Nakia, so right there you know he is in tune with the land. He probably cries one silent tear when he sees litter.

- Cut to Farrow swimming in the lodge’s outdoor heated pool. I’m sure Corman’s deal with the resort stipulated they film all the amenities for maximum advertising impact. With this accomplished, they move the characters inside…to the also fabulous indoor pool!

- Forster, fearing a huge outcropping of snow Hudson and his data-obsessed men refuse to deal with, steals some explosives to handle the job himself.

- Bruce the skier has been shacking up with the wife of a TV interview guy who coincidentally has just arrived to film a report on the lodge and oh, the awkwardness. Since the usual signal that we’re supposed to ‘care’ about something like this is that the TV Guy would be played by Robert Wagner and his errant wife by Susan George and Bruce the Skier by Peter Fonda, and since they aren’t, well, you know.

- Aiieee, a scene in the lodge’s disco! Well, it was the ‘70s. Then we cut downstairs to the lodge’s luxurious dining room with the parades of waiters bearing gourmet desserts passing by. Product placement obligations: Check!

- Speaking of romantic triangles, I guess they’re also forming one with Hudson and Farrow and Forster. This one IS better cast, and I still don’t care. So much for that theory.

- Of course, part of the problem is again the leads. Hudson just can’t work up much enthusiasm for evincing a Great Love; he’s always come from the block of wood school of acting. And Farrow is in full drab mode here. This makes Forster’s instant attraction to her inexplicable, except as a matter of scripting. If Farrow had a more vivid personality, it could work as a case of Forster seeing some depth in her that the tons of sexually available ski bunnies all around the place don’t have. Farrow doesn’t remotely suggest anything like that, though. Even her posture is slumpy and wilted.

- Moreover, this triangle aspect makes Forster come off as kind of an asshole. Hudson always warmly greets Forster as a friend, and then the latter starts sniffing around Hudson’s ex-wife, when the guy is clearly trying to patch up his relationship with her. Nice.

- The only question is which of the rival males will Tragically Kack It to clear room for the other. The obvious bet is Forster. Despite the groovy tone of Free Love they attempt here, chances are the film will go all conventional at the end and opt for the married couple. Besides, Hudson is the bigger star, sort of, and they usually win.

- Actually, as the film now jumps from secondary character to secondary character to Make Us Care, I realize I don’t really like any of them. It’s hard to invest that much in people whose primary—indeed, only—trait is We Are Young and Glamorous and Looking to Get Laid.

- Outside it’s snowing, just as Forster warned. Cue ominous music.

- Farrow heads out with Forster. They go to his cabin, which of course is ridiculously sweet. Yawn. The romantic scenes with these two are downright painful…although I guess I shouldn’t complain, we could be getting love scenes between Farrow and Hudson. Then we cut to various other couples getting it one in a safely PG fashion. Although in 1978 this allowed for a brief butt shot and some sideboob. And oh, the eroticism. Say, when exactly are they going to start killing people?

- Oh, but Tina, the TV Guy’s slutty wife, finds her lover shacked up with Peggy Fleming Haircut Skating Girl (as opposed to Fragile Blond Skating Girl). She completely freaks out and runs away, refusing to seek succor in the arms of the husband who still loves her. So obviously she’s going to die soon.

- The storm gets worse. Bum bum bum.

- In the morning…more stuff. Hudson has shacked up with his assistant Susan, who briefly walks nude through some shower steam in the background, showing a carefully calibrated amount of near-nudity. Then we get a full shot of her chest, and then another of her ass. Ah, what you could get away with in a PG movie back in those pre PG-13 days. I’m sure Corman mandated the exact maximum seconds of nudity you could get away with for that rating.

- Meanwhile, Hudson is yelling on the phone again. If you enjoy hot Yelling On the Phone action, then this is the movie for you!

- We cut to Farrow waking up in Forster’s bed. Thank goodness we were spared seeing any such antics with those two. Forster, meanwhile, has left to trudge up the mountain and set off the explosives he stole and break up the ever-growing snowcap. Between that and a love scene with Farrow, well, I’d have chosen the same.

- Tina goes back to Bruce and OH MY GOODNESS I CAN’T STAND IT ANYMORE PLEASE START KILLING PEOPLE I’M BEGGING YOU!!!!!!!

- Things I Learned: Never bring a knife to a glass of milk fight.

- Hudson is premiering “The world’s first international snowmobile race.” One of the contestants is a woman (Whaaaaa?!), another the man “who made snowmobile racing a dirty sport!” (Dick Dastardly?) Sure enough he goes around kicking and nudging and knocking other racers out of the way and such. Justice is served when he hits another snowmobile and crashes. Wow, that was a great minute of the film.

- Next is a cross-country skiing race. Meanwhile, Forster uses a cannon (really) to shoot a RPG or something into the snow pack. Yes, he should definitely be taking this upon himself. By the way, the snow doesn’t break loose with his first shot. Yep, it sure seems “unstable.”

- More winter sports stock footage. Awesome.

- Forster’s second shot does it. The snow cap is safely reduced—or so he thinks (presumably).

- Back to Bruce and Tina and TV Guy and AHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH!!

- Figure skating. Man, the excitement mounts. Peggy Fleming Haircut Girl of course does great. But what about Fragile Blond Skating Girl? Will she ever learn to believe in herself?

- Somebody Hudson has been demanding all picture fly up with “the file”—maybe it’s the politician mentioned earlier, but frankly I just didn’t care enough to pay that much attention—is doing so in a small plane despite another bad storm starting up in the mountains. Bum bum bum.

- To show his sensitive side, TV Guy takes a lonely kid up with him on a ski lift.

- Fragile Blond Skating Girl starts her routine.

- The plane! The skater! Intercut! Intercut!

- Bruce makes a sex date with a 16 year old, providing she brings “some ID.” He’s a classy dude.

- Uh, oh, a mountaintop ice pack begins to breaks up. I guess it’s not the one Forster broke up, but another one. So good work there, Forster. Anyway, for little apparent reason the aforementioned plane then crashes into it, and with a bit more than half an hour left, we’re finally good to go. Wheeee!

- Bad special effects! Stock footage! Unconvincing miniatures! Styrofoam snow boulders! Rinse and repeat!

- Snow hits the station controlling the ski lift and smashes everything up. Cartoon sparks—seriously—are drawn in so that we ‘get’ that the controls are ruined. Oh, noes, TV Guy is trapped way above the ground with that kid.

- Gary the Other Skier is et by the Avalanche. Elsewhere, the Avalanche starts chasing Bruce down the mountain! He ties to outski it but it’s no good! No more borderline pedophilia for that dude!

- Mass carnage! Dozens of extras get kacked! Oh, the Humanity!

- Fragile Blond Staking Girl finally overcomes her fears and performs a perfect routine! It’s a Heartwarming Triumph of the Human Spirit! Then the Avalanche comes along and kills everyone, sweeping her away just as she executes her final perfect spin. I’m sure this was meant to be tragic and all, but I can only report that back when I saw this in a theater in 1978 (thirty-two years ago!) the audience broke out laughing when this happened.

- The lodge gets hit! Styrofoam snow everywhere!

- A cook pulls a big pot of boiling soup on himself. Is that a stock shot from Earthquake? I thought I remembered something like that in that film, although I haven’t seen it in thirty plus years now.

- Tina (wearing a Bruce jersey!) is about to swallow a bottle of pills and kill herself. Instead, the Avalanche gets her. Oh, the irony!

- So, let’s see, a bunch of people are dead. (Finally!) Hudson—I think it’s him—is outside, buried and trapped under some snow. Farrow is trapped in Forster’s place. Forster is OK on the mountain. TV Guy and the kid are trapped high up in the precarious ski lift. Nolan and Schnook Guy (her sidekick character) are trapped in the lodge’s dining behind a wall of snow. They are threatened by leaking gas.

- The broken gas line causes an explosion in the kitchen, and more of the staff gets killed. I’m still thinking this is stock footage from Earthquake or another movie.

- Rescuers arrive. Hudson makes it back to the lodge and is met by Susan. Maybe it was Hudson trapped under the snow and he got out, or maybe it was another one of our fascinating characters I’m forgetting and he’s still trapped.

- Like a lot of these things, the actual disaster part is short-lived (one advantage of The Towering Inferno was that it was an ongoing disaster), so now we’re in the traditional Aftermath section of things. This involves attempts to rescue various folks in jeopardy, allowing for satisfying subsidiary deaths and the occasional ‘heartwarming’ success.

- Farrow comes limping down the mountain. She is picked up by TV Guy’s crew. She meets up with Hudson at the lodge.

- By the way, TV Guy’s crew notices TV Guy caught up on the ski lift, and decides to just film him and the kid! I mean, I guess, why not, they’re not in a position to save him or anything. On the other hand, we don’t see them going for help, either.

- It was Bruce trapped under the snow. He’s still alive, but trapped and alone.

- Schnook Guy tries to keep Nolan warm, but she’s in bad shape. He begins to try to tunnel his way out, and meets Hudson tunneling from the other side. He’s saved! Wow, my heart just grew three sizes.

- Nolan doesn’t make it. Yawn. Oh, wait, she did! Yawn. And she’s still an irrepressible life spirit!

- Bruce is saved! Break out the sexy high school sophomores! No wait, he’s dead. I wish they’d just make up their minds on these things.

- Firefighters and Hudson head out to the ski lift. TV Guy & The Kid are barely hanging on, since their seat has fallen. Then the damaged machinery starts up again as the firefighters try to get the net in position! If it’s not one thing it’s another.

- TV Guy saves the kid, but just as he prepares to jump, he is hit by an electrical charge and moreover misses the net as he falls. Boy, if it’s not one thing it’s another.

- Lamely, something else (c’mon, don’t make me pay attention to this thing) puts the ambulance carrying Nolan, Schnook Guy and Farrow in More Peril. Sigh. Hudson and Nick grab a jeep and ride to the rescue.

- It’s only at this point that the ambulance is seen starting to lose control, and then only because the driver is driving like an idiot. It goes off a bridge. Uh, let’s see, Farrow is thrown clear, but left hanging above the chasm. I assume both Nolan and Schnook Guy have now officially bought it.

- Forster and Hudson arrive. Farrow is hanging from the dangling wreckage of the bridge’s guard rail. I assume one of the guys—my money’s still on Forster, although sometimes they kill the biggest star in these things for maximum tragedy—falls trying to save her, thus neatly ending the romantic triangle.

- Hudson’s stunt double begins climbing down to Farrow’s stunt double. Forster stays topside to toss down a rope. And Hudson’s mom just bought it. It’s going to be hard for Farrow to blow him off now.

- Nope, both Forster and Hudson are still around. Weird. However, as expected, Farrow opts for Hudson. And for the first time, Hudson admits, “I am responsible. I caused all this.” He means, you know, the deaths of literally dozens or even hundreds of people. Including his mom. However, this showing of vulnerability is portrayed as a moment of growth, and wins from Farrow a declaration of her love for him. Ahhhhhh. Then it was all worth it in the end.

- But then she leaves. So I guess she chooses neither of the guys. Smarter than I thought, that one. Hudson is left wandering the literal ruins of his dreams all alone, like a beefier Miss Havisham. The End. Wow, great ending.

- Two and half minutes of end credits in a film 90 minutes long? Roger Corman, you magnificent shameless bastard!

IMMORTAL DIALOGUE:

A reporter questions a recently arrived pro skier Bruce:

Female Reporter: “Bruce, from the beginning you seemed to thrive on risk! Have you ever known fear?”

Ultra Cool & Laid Back Bruce: “I never thought about it. I ski like I breathe, or talk, or make love.”

Female Reporter: “Oh, ho! It kind of makes me wonder what you do best!”

*******

Whatever one thinks of the film (and I doubt there’s anyone who thought much of it), Corman’s unswerving allegiance to the almighty dollar paid off again. The year after Corman made Avalanche, his old associate Sam Arkoff at AIP—James Nicholson was by this time deceased—released his own disaster picture, Meteor. Like many mini-moguls before and after him, Arkoff was about to make the fatal error of attempting, at long last, to achieve stature in the industry. In Hollywood, those whom the gods would destroy they make crave respectability.

Mini-moguls generally spend years, sometimes decades, toiling in the shadows of the major studios. Almost invariably, there comes a point where they abandon the small movies that kept them afloat and try to move to the big table. This generally involves putting out either one big budget movie or a slate of them. Either way, it’s risking all on one roll of the dice. Sadly, they inevitably learn the gambler’s oldest lesson: The House always wins.

Arkoff proved all too representative of this. Getting on in years, he hoped to make AIP something more before he retired. His final gambit in this regard was to attempt to his own Disaster Epic, the quintessential genre of the 1970s. All the warning signs were there, including the fact that by 1978 the Disaster Movie was undeniably on the wane. Even so, Arkoff bankrolled his movie with a gigantic budget of $16 million, as big as or even bigger than any of the major studio movies such as Earthquake or Towering Inferno.