Introduced in 1969 by the weakest of the big three networks, The ABC Movie of the Week was a major gamble. It not only proved a success, but one that revolutionized primetime network television. Caught off guard, NBC and CBS scrambled to catch up.

This was, however, the product of something we’ll never see again: a mass culture. People who grew up in the Home Video and Cable Age, much less the Internet Age (and the IPod Age, and the TiVo Age, and the Video Game Age, etc.) will never really understand what it was like to live in a country with so few entertainment options.

In many ways, the current situation is obviously, markedly superior. Today’s literally endless array of entertainment choices allows both individuals and small groups to seek out precisely the sort of leisure activities that satisfy them most deeply. People now literally program their own entertainment universe, bypassing the judgment of others save those they freely elect to follow.

Things were vastly different when I was a lad, however. When I was growing up, television was the sole form of electronic entertainment in the household, save for radio or phonograph records. Past that, there were books or board games. Otherwise, you had to leave the house to seek entertainment. Even then in many parts of the country that meant checking out a single local movie house or drive-in, which generally offered one screen and showed one movie a week, or at best a double feature.

Television was vastly more limited, as well. There were, of course, the mighty Big Three networks. At best, your other options might be a major local independent channel—in Chicago, this was WGN, a national powerhouse—and a PBS station. Past that, you might have had a couple of low-watt UHF stations.

In those days, most TVs worked like an AM/FM radio. If you wanted these smaller stations (the early broadcasters of the sort of junk cinema my compatriots and I grew up on), you had to literally turn a switch on your TV set from VHF to UHF. Then, if you were lucky, the station’s signal was strong enough that day that you didn’t have to constantly play with the rabbit ears to receive the broadcast. If you weren’t, you experienced the joy of potentially watching a movie for two hours only to have the signal cut out during the last ten minutes.

And, of course, TV literally turned off in the wee hours of the morning. I wonder what today’s youngsters would make of hearing “And this concludes our broadcast day,” followed by the static or hum of a non-signal. Not even an informercial was to be found, just a test pattern screen until (yes, really) the Farm Report ran at five or six in the morning.

The Big Three networks dominated the ratings to an extent literally impossible today. Let’s take 1972, for instance. The top television show was the sitcom All in the Family, which gleaned a yearly rating of 34 million households. Today’s American Idol, generally regarded as a modern TV “phenomenon,” at its absolute acme once drew 38 million viewers, during the finale of the show’s second skein.

Look at those numbers again, though. All in the Family averaged 34 million households. This is salient because back in a day, again because of limited entertainment options families were much more prone to gather together and watch programming as a unit.

This is largely because most homes would have, at best, had one ‘large’ color television, by which I mean one with a 25 inch screen. Any other sets in the house were most likely black & white sets with 15 to 19 inch screens. As staggering as it might seem now, 1972 was in fact the first year in which the country’s color TV sales outnumbered those of black and white sets.

As such, a ‘household’ back then generally provided a more sizable audience than you might think. Families were rather larger then, too. In my suburban neighborhood, three to four kids (I have three younger brothers and sisters, for instance) per family was the norm, and five to seven children was not uncommon. Indeed, my onetime step-father was one of nine kids. Admittedly, that was considered a lot even in the early ‘70s, although not as freakishly so as it would be today.

Given such demographics, a more rational point of comparison is ‘share;’ i.e., what percentage of active TV sets were tuned to a certain show. All in the Family garnered a yearly average share of 54%, meaning that when it was on more than half of all TV sets being watched during that time slot were tuned to it. American Idol, even during its very peak, gleaned more like a 33% share. And again, that is considered by today’s standards a mind-blowing ratings juggernaut.

In 2005-2006, for example, Idol averaged about a 31 share, and thing deteriorate quickly from there. The number two most watched show that year, CSI, garnered but a 21 share. The 20th highest rated network series in 2005, Cold Case, drew a lowly 8 share. In contrast, the number 20 show in 1972, Bonanza, had a 34 share. This means that there were at least 20 shows that topped 2005-2006’s number one television ‘juggernaut,’ and downright murdered CSI in terms of share.

I can support this anecdotally, as well. I was a kid in the late 1960s and early ‘70s, and chances are almost all of your schoolmates were watching the same shows you were. After all, there were really only three program options at any one time.

Given this, there was often but one show in each time slot likely to appeal to kids, whether it was a sitcom like The Partridge Family or an action show like Emergency. (Sadly for me, Emergency ran against the powerhouse CBS sitcoms All in the Family and Bridget Loves Bernie, and my step-dad ruled the TV dial with an iron fist. All in the Family it was.)

Unsurprisingly, that era’s event programming was even more valuable. If a regular show could average over half of households, a big sporting event, an Oscar telecast or the network premiere of a blockbuster movie could draw an even more impressive audience. The final episode of M*A*S*H, for instance, drew a staggering 77% share; 77 of every 100 televisions being watched during those two hours were tuned to CBS.

As such, the Big Three bid up the prices for the hit movies of the day. Again, remember that in these days of yore, there was no home video. If you didn’t live in a big city with revival theaters—New York was the mecca of movie buffs, supporting at one time literally dozens of repertory movie venues—then once films left the theater the only way you would ever get to see them was when they ran on television. And with only a handful of channels, big movies like The Sound of Music or The Guns of Navarone playing on primetime TV was indeed ‘event’ programming.

ABC was, to its regret, traditionally the little kid brother among the Big Three. Some years they failed to have a single one of the top ten shows. As such, they had less money to bid for the biggest movie titles.

In response, then ABC programming head Barry Diller—later one of the founders of the Fox Network—came up with the idea of instead producing a weekly ‘premiere’ movie made especially for the network. It was a pure roll of the dice, but it paid off handsomely. The upstart network was soon running two separate Movies of the Week, one on Sunday and the other on Tuesday.

Indeed, in 1970 the Tuesday night edition of the MotW was one of ABC’s only two top ten shows, the other being The FBI. And the Sunday night MotW was in the top twenty, despite running against NBC’s top ten powerhouse Bonanza. With ABC suddenly an emerging threat, CBS and NBC were left scrambling to catch up. Predictably, their response was to broadcast their own TV movies. The result was that the face of network television was majorly altered for much of the following decade.

Given that the Big Three produced literally hundreds of such films in the ‘70s alone, the oddest thing is that almost none of them sucked. (Things went downhill to some extent in the loosey-goosey ‘80s, though. Even so, most of the laughable ones even then were pilots—generally failed ones, although a few chucklefests like the E.A.R.T.H. Force ‘movie’ did result in short-lived series—and the Cabal has decided to put aside such pilots for a separate future roundtable.)

My esteemed colleague Liz Kingsley, in her review for this roundtable, noted “the MFTVMs [Made for TV Movies] of this era were, at worst, always professional works; the directors, the writers and the actors involved were the kind of solid, reliable types that just don’t seem to have a place in the entertainment industry any longer, more’s the pity. As a consequence, a remarkable number of these rapidly-shot, inexpensively produced little movies hold up astonishingly well; and some, indeed, are wonderful and memorable by any standard.” [Emphasis in the original.]

Liz’s assessment is utterly correct. Indeed, an almost exact analogue to the MFTVMs of the ‘70s would be the B-movies the major studios produced back in the 1930s and 1940s. These would be ‘B-movies’ in the original sense; briskly produced low budget movies churned out with factory precision to occupy the lower half of a double bill under the respective studio’s ‘A’ pictures.

To promote efficiency, and again like the MFTVMs of the ‘70s, these B-movies were manufactured by discrete departments of each of the major studios. (Although the smaller studios, like RKO where legendary horror producer Val Lewton worked, basically specialized in B-movies.)

Like the network MFTVMs of the 1970s, these films were inevitably highly formulaic in nature. Innovation, after all, took time and time was money. Within those constraints, however, these pictures covered a wide variety of genres, including westerns, comedies, musicals, romances, crime thrillers, horror movies, mysteries (a much more popular type of film back in the day) and more. Each studio also had their recurring B-movie series characters, ranging from Ma & Pa Kettle to Blondie & Dagwood to Mr. Moto to Boston Blackie to the Bowery Boys.

In contrast, partly because the most popular ABC Movies of the Week often acted as backdoor pilots for ongoing series, they were rather less likely to feature recurring characters.* In a few cases, a single follow up movie was produced. Following that, either the pictures produced an ongoing programming—such as Kolchak: The Night Stalker—or they didn’t, as with the nifty Louis Jourdan supernatural investigator flicks Fear No Evil and Ritual of Evil. In either case, the MotW then moved on to new territory.

[*NBC followed the venerable B-movie model even more thoroughly, however. Their completing MFTVM innovation was The NBC Mystery Movie. These did indeed feature recurring characters whose adventures appeared via a rotating roster of 90 minute or two hour movies. Such characters as Columbo, McMillan & Wife, Banacek, Hec Ramsey and McCloud, among many others, were products of this.]Sadly, MFTVMs of this vintage are not reliably available. Some few of them have received standard DVD releases (The Norliss Tapes, Trilogy of Terror), some are available through official studio DVD-R programs like the Warners Archive program. The latter, for instance, offers the classic, soon-to-be-remade horror film Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark. Other titles were put out in the days of yore on VHS, and can now be found in crappy but cheap (and almost certainly pirated) editions in those budget DVDs packs from companies like Mills Creek. Many, also similarly fallen between the cracks, can be watched for free on YouTube.

Given that I couldn’t find a dead awful MFTVM (especially as we decided no pilots, and I wanted to stick with the ‘70s), I opted for one that was just plain weird. Nor did it hurt that I already owned a pretty good copy of it, given that it was itself part of the Warners Archive and I’d bought a DVD-R of it last year.

How to account for how bizarre our current subject is? Well, it was one of a handful of films ABC ordered from a strange pairing of partners, Rankin / Bass (best known for their puppet holiday specials, like Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer and The Year Without a Santa Claus) and Japan’s Tsuburaya Productions, the makers of Ultraman. Their most famous coproduction I reviewed way back in the day, The Last Dinosaur.

(I would love, however, to see their third and final co-production, 1980’s The Ivory Ape. That features Jack Palance as an ultra-macho and obsessed hunter out to kill the titular beast, and opposed by a pair of more sensitive characters. If that sounds familiar, it’s because that’s pretty similar to the plot of The Last Dinosaur. And it’s set in Bermuda, just like our current subject! Talk about continuity.)

Perhaps bereft at their inability to showcase young cyborg schoolgirls with talking cats being raped with tentacles, the film instead is a perverse Mulligan’s stew of incredibly weird and disparate ingredients. Plot threads abound, and many of them remain hanging loosely when events are done. In a less expertly assembled package, this would work against the film. Here, it proves easy to pick what we want and ignore rest. It’s less a stew than a salad bar.

Some of these ingredients go together smoothly or even echo one another, like the giant turtle and Oscar winning actor Burl Ives. Others, not so much. Lost loves, madness, shipwrecks, tragic backstories, ghosts (maybe), Lovecraftian-esque elder gods (sort of), underground labs, Apollo Creed playing a manqué Ahab and more are all offered up with incoherent abandon.

The movie’s not even close to being bad, although it’s certainly not great. It’s oddly memorable, though. Chances are that if you saw it back in the day, especially if you were a kid (or a young woman entranced by the supernatural-tinged romance it offered), you at least vaguely remember it.

I did, and a quick Google search suggests I was not alone. Review of this film, many from folks excitedly seeing it for the first time since it was broadcast, dot the Interwebs. Indeed, the fact that Bermuda Depths was one of the first releases under the Warners Archive rubric suggests an audience clamouring for the thing.

Before I begin the review proper, however, I exhort you, Gentle Reader, as I always do when writing about a non-bad movie: If you haven’t seen the film, and think you might ever have any interest in do so, take a look at it before reading the spoiler-laden examination that follows.

We open rather decently, underwater with bubbles rising up against a black background that indeed suggests ‘depths.’ The score is workmanlike and incorporates whale song, and again serviceably evokes water and the Mysteries of the Deep* and all that sort of business. The title itself quickly soon swims towards us in a wavery font.

[*Due to the whole surge of interest in paranormal phenomena and such during the ‘70s, there is little doubt the title was also meant to suggest the Bermuda Triangle, which was the subject of several other MotWs such as 1975’s Beyond the Bermuda Triangle and Satan’s Triangle, not to mention 1978’s The Bermuda Triangle and the 1977 TV show The Fantastic Journey, starring—who else?—Jarred Martin. The Triangle has remained a popular subject of TV inquiry, having inspired well over a dozen TV movies since the ‘70s as well.]The rest of the credits play over some lushly beautiful underwater footage. Indeed, the film will continue to expertly exploit nature’s grandeur. This includes the gobsmacking beauty of its female lead, 22 year-old Connie Sellecca, who is tracked swimming below these waters, failing to rise for air for a weirdly long period.

The current images of undersea splendour are accompanied by the wistful ballad “Jennie”. Like the movie itself, the theme isn’t brilliant or anything. Yet it proves a solid, professional effort. The song’s lyrics foretell that the doomed love for a mysterious woman will be a central theme here.

The tune lacks the high camp value of the Shirley Bassey-esque theme to The Last Dinosaur, but it readily establishes a melancholy tone that proves one of the picture’s strengths. Flaws and its own manifold goofosity aside, this will prove a much more serious affair than the madcap Boy’s Adventure tone of The Last Dinosaur.

Credits by the board, we get right into things. The beautiful woman we’ve been watching, wearing a corset-like black swimsuit and what appear to be the tattered remains of a shirt around her waist, emerges from the Bermuda surf. Shot through a naturally circular rock formation—you almost can’t not take advantage of the area’s fecund natural beauty—she approaches a young beach bum taking a nap in the sand. As he slumbers she fingers the seashell necklace he wears, gazing upon him with limpid eyes and tenderly stroking his face.

However, her touch inspires the sleeping man to dream about his childhood. A boy of perhaps five or six, clearly the younger version of the dreamer, finds a largish turtle egg on the pristine beach. (Again, the scenery here is just stunning.) The boy calls out to Jennie, who unsurprisingly proves obviously the younger version of the woman. She’s even wearing the same corset / swimsuit, although it doesn’t have quite the same effect on her.

The children clearly are very close. Indeed, their patently deep yet innocent bond—emphasised by the pastoral music playing on the soundtrack—and the gorgeous beach bring back memories of 1980’s The Blue Lagoon. Indeed, our blonde male lead here somewhat resembles that film’s Christopher Atkins, while Sellecca is a willowy brunette like Brooke Shields. Entirely a coincidence, of course, but still a somewhat amusing one.

The pair watch with evident wonder as the egg begins to hatch. Then the flashback skips forward several years, with the pair clearly closer to adolescence. The sea turtle that emerged from the shell is now basically their pet. I rather dig turtles, especially the big ones, so this didn’t hurt my appreciation of the film any.

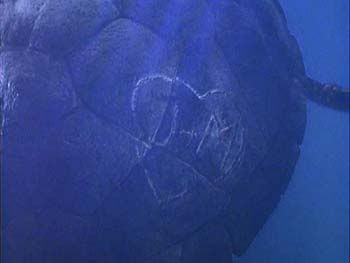

The children have grown even closer, with incipient yet still indefinable feelings of romantic interest starting to burgeon. Witnessing a key moment, we see the boy etching their initials within a heart into the turtle’s shell. For her part, Jennie strings some seashells into a necklace and presents it in return. This is, of course, the necklace that the young man today yet wears around his neck.

However, their friendship ends with abrupt tragedy one day shortly after. Waking from a foreshadowing nap—where he lay snoozing next to an uneaten apple! Symbolism!—the boy looks out to sea. There he spies the turtle swimming away. Jennie, calmly hanging onto the animal’s shell, disappears beneath the waters with it. The boy never sees her again.

The flashback continues, filling in more of the lad’s backstory. His father is a widowed scientist, and the two live in a rather swank cliff top house. Moreover, this is built over a subterranean grotto, accessible via a staircase. Down here Dad has a little lab area overlooking the waters of the interior lagoon.

It’s night time, perhaps even the same day during which Jennie disappeared. The boy’s father tucks him into bed and then heads down to the grotto. All this is sans dialogue, by the way; we learn of the father’s occupation when he pauses to don, what else, a white lab coat. Still, it’s a carefully besmirched one, which does add a certain verisimilitude.

Unseen by the occupants, a gigantic shadow appears looming over the house and cliff side, accompanied by more whale sounds. Soon either a storm or something more mysterious begins to tear at the house, and it and the rocks below begin to crumble. (This is the film’s first special effects sequence, unsurprisingly achieved with miniatures, and probably the most successful.) As debris falls around him down in the grotto, Dad is seemingly—maybe—approached by something horrible. Screaming, he falls into the water, presumably with fatal outcome.

Say what you will, that kid had a rough childhood. Hell, it’s practically Dickensian.

Backstory established, the boy’s older self awakens. By this time, however, Jennie has departed, leaving him none the wiser. However, as he pauses, he is shaken to see what appears to be a woman swimming out in the surf. This mirroring of scenes is nicely done, by the way. Again, they’re not reinventing the wheel here, but they do know what they’re doing. And the storytelling is refreshing clean and straightforward. Again, these are traditional strengths of B-movies.

After pauses to gaze upon the ruins of his former home, the man heads into town. There follows several minutes of sightseeing footage as the guy mopeds around town, accompanied by cheerful music. Presumably they got more cooperation out of the locals for including this stuff, but given how lovely everything is, it’s actually a fairly pleasant little interlude. (And you can’t blame them for making a film set in Bermuda—free working vacations for everyone!)

Our Hero travels to a dock, where he approaches an old fishing trawler. There he calls out to a muscular chap named Eric (Carl Weathers!). Eric greets him with surprised joy, treating him like a prodigal younger brother. It’s here we learn our protagonist is named Magnus Dens. Not as plummy a moniker as Maston Thurst, but it will serve.

Eric isn’t a fisherman, though. The trawler is in fact a research vessel. Eric works with the currently unseen Dr. Paulis (Ives), who was an associate of Magnus’ father. Eric worked with both of them as a student, which is how he knows the somewhat younger Magnus. Weathers’ naturally ebullient personality here nicely sells the idea that the two men are fairly close.

Further backstory is filled in. We learn that Magnus has moved from one college to another. His embarrassed expression upon hearing Eric jest that he’s the “drop out king of the world” suggests that there weren’t entirely copasetic motives for these moves. Eric, meanwhile, mentions a wife, Doshan. Indeed, seconds later the two take the boat out to sea. We then cut to seeing Doshan gazing worriedly in their direction from a nearby dockside window.

Magnus helps Eric cast out a large fishing net. Then they head inside the boat, where Eric introduces Magnus to the aforementioned Dr. Paulis. As played by Ives, he’s by turns avuncular, cranky and sage, but always believably a scientist. (And he doesn’t even ever wear a lab coat or smoke a pipe!) Ives plays him throughout as a person rather than a Scientist!, and generally shows the kids how this acting thing is done.

The meeting is interrupted by the boat being violently jarred. Eric runs and pulls up the net, which is massively rent. Paulis notes that this is third heavy net that’s met a similar fate in this area, and judges they are close to their quarry.

Back at the dock we get a closer look at Doshan, who proves to be a knock-out. On the other hand, what sort of wife do you expect a guy who looks like Carl Weathers to have? (On the other hand, Weathers proves that no man, no matter how exaggeratedly muscular, can pull off short shorts or midriff-baring shirts.)

Later they are having dinner with Paulis, who has a poster of a giant turtle skeleton on his wall. He explains that they are doing field research in teratology, which he defines as the study of abnormal growth in animal life. (Well, partly, maybe. In practice it’s more generally the study of birth defects.)

He also talks about “the unknown creatures” living in the unexplored ocean depths. Again, that’s more cryptozoology than teratology, I’d think. Bonus cliché points, however, for his noting that these deeps remain unexplored “even in this space age.” And sure enough, mention is inevitably made of the coelacanth.

Here we meet the film’s one dicey character, not to mention it’s most undeveloped. This is Delia, the local native woman prone to ominous warnings about the supernatural. Now, to be fair, these women (and their occasional male counterparts) tend to appear in films in which the supernatural does indeed exist. As such, we should probably treat them with a bit more respect, especially since they often make the stiff-necked, generally white scientists in the movies look like chumps.*

[*This as opposed to outright wince-inducing characters like black maid Eulabelle, given to yelling “It’s the voodoo, I tell you, the voodoo!” throughout the nuclear fishman movie The Horror of Party Beach. At least here Delia is portrayed as a wise-woman.]Delia and Magnus exchange pretty exaggerated Significant Glances, by the way. Perhaps there was an excised subplot wherein Delia worked for his father when he was a boy, but if so, I failed to glean any real trace of it remaining. It’s not much of a stretch, though, since Delia is now working for an associate of his deceased father. In any case, that pretty much rounds up the cast, so now we can continue on with the plot.

Eric offers Magnus the couch at their place, but Paulis counters by offering Magnus a spare room. This is to Doshan’s evident relief, and later she and Eric get into an argument about it. It turns out that Magnus has been hospitalized for psychiatric issues—no big surprise, really—and she worries that he will bring trouble with him. Eric, meanwhile, wants to help Magnus out of the best of his ability.

This is a nice touch, and I like the fact that Eric is (at least in this regard) so altruistic. Even so, the film thankfully doesn’t make Doshan seem bitchy for these concerns. Indeed, considering the track record of the numerous doomed personal relationships in this film, her apprehensions come off as entirely reasonable. And indeed she has good cause to be apprehensive for Eric’s sake, although ironically not because of Magnus.

In any case, Magnus’ history of mental instability is a nicely judged plot point. Traditionally the best ghost stories, in print and onscreen, feature a large dollop of ambiguity. Are supernatural things actually occurring, or are they all figments of the character’s imaginations? Ghosts are traditionally most effective when their existence remain just a bit in question. The Haunting (the real one) and The Innocents are probably the best two ghost movies, and they feature this idea in spades.

And indeed, we learn that Jennie was, even back when she was supposedly cavorting with Magnus was a child, considered by everyone else to be his imagined playmate, an invisible friend. This idea continues, as for the majority of the film no one but Magnus sees her adult counterpart. And if Magnus is unstable, is his quest to learn “the truth” behind his father’s death a further danger to his fragile psyche? Could Magnus just be crazy, or even the victim of a hoax?

Adding weight to this latter possibility is Paulis’ gently mocking reaction to being told that Magnus’ supposed girlfriend has identified herself as one Jennie Haniver. As Paulis explains, accurately, a Jennie—or Jenny—Haniver is a faked nonexistent animal created from the parts of a real one, like the jackalope. (Similarly, the skeleton of one of the titular beasties in the 1972 MFTVM classic Gargoyles is initially dubbed a similar fake. By the way, that’s one of the movies you can watch for free on YouTube.)

The film offers another wrinkle, though. Yes, a Jennie Haniver is in real life a faked, nonexistent animal. However, a bit later Delia explains to Magnus that (at least according to his film) the term was inspired by a figure of legend, a woman who died in a shipwreck. Here we get another fun effects sequence, cutting to a flashback in which an old timey wooden ship is being knocked around by a vicious storm.

Delia asserts that Jennie didn’t actually die, however. As the ship is near to foundering, and faced with a death she is not prepared for, Jennie (also played by Sellecca, of course) kneels on the ship’s deck to pray.

“But her prayers were directed to him, the one below,” Delia explains. “Let the rest drown, but if he would save her, she would do anything.” And so a deal is struck, and Jennie leaps into the ocean to join her new master. She sinks down towards mysterious lights and the now expected whale song. Now her beauty would be preserved forever.

Since that day, Jennie’s legend has grown. Apparently she acts more like a banshee than a siren, however, as she is said to sometimes appear to men before their imminent death at sea. In such cases she sometimes wears the guise of a beautiful young woman, but in others is seen as (bum bum bum) a little girl. Not exactly easing Magnus’ mind, Delia is the only one who believes Jennie is real. But she also believes that he is meeting with the Jennie of legend, an immortal harbinger of doom.*

(*Anyhoo, exposition duties duly discharged, Delia’s utility to the plot is over, and she disappears from the rest of the film.)

Whatever the truth is, Jennie continues to appear when Magnus is alone, and their romance continues apace. Her hold on his imagination only tightens when, early on in things, he dives too deeply in following her swimming form. He nearly drowns, and wakes to find she has rescued him and brought him ashore. (Shades of Splash.) Plus, well, Jennie looks like a 22 year-old Connie Sellecca wearing a deeply cut black swimsuit that’s heavy on the décollage, so you do the math.

Despite the rescue, though, Jennie’s motives toward Magnus remain suspect. After all, she was the one lured him down below in the first place. Was this an accident, or rather her intent?

As the weirdness continues, Paulis and Eric’s increasingly irritable disbelief regarding Jennie’s existence begins to have its effect. Adding to Magnus’ fears are odd details, as when Jennie mentions how she loved dancing “the quadrille” at her father’s “great hall.” The quadrille is a dance that was popular several hundred years ago, a fact which naturally adds to Magnus’ mystified anxiety.

And so proceeds the main romantic plotline, and then there’s the main action plotline. Eric might be a great friend and a loving husband. However, most every sea monster story needs an Ahab analogue, and apparently Eric drew the straw.

The resemblance is so obvious that they even try to get ahead of it. Paulis refuses to join in Eric hunt to kill Whatever Is Out there (they don’t know it’s a giant turtle yet), and tells his colleague outright that he has “Captain Ahab Syndrome.” Hey, you might as well cop to it, right?

Speaking of, that means three of the four* Rankin/Bass – Tsubaraya coproductions; this, The Ivory Ape and The Last Dinosaur; all revolved around an obsessed character seeking to kill a fantastical beastie of some sort, and opposed in doing so by a scientist or two.

[*The other movie was The Bushido Blade, starring Dinosaur’s Richard Boone as Matthew Perry—the Commander, doofus, not the Friends actor—and Toshiro Mifune. Sadly, the result was quite tepid, if my recollections are accurate. The film remains more memorable for utterly wasting it’s often elliptically seen supporting cast, including James Earl Jones, Laura Gemser, Mako and Sonny Chiba.If you’re thinking you might have seen this movie and it was actually kind of good, you’re probably thinking of Mifune in Red Sun. Both films feature a moustachioed American joining with Mifune to search for and retrieve a stolen samurai sword. In Red Sun Mifune’s co-star was Charles Bronson.]

Still, it’s nice that Eric is never really made into a villain. He just seems to lose his grip (and it’s pretty noticeable that on the hunting trip he’s constantly chugging down beer), but otherwise mostly remains a nice guy. This makes his eventual tragic death—oops, sorry—generate a bit more of a kick, especially in that his demise is pretty nasty (not to mention right out of Moby Dick).

Even more so is that of Paulis. He was actually leaving the island to protest Eric’s actions, but stayed behind out of worry for his colleague. Losing contact with the trawler, Paulis flies out for a looksee in a helicopter. Needless to say, that seals his fate. Ken’s First Rule of Transportation: Never ride in a train or a helicopter in a giant monster movie.

Paulis’ death scene, sadly, is also the film’s goofiest moment, a guffaw-inducing bit wherein the gigantic turtle leaps up from the water so to force a collision with the ‘copter. The latter, of course, is an obvious plastic jobbie on wires, and its subsequent crash and explosion also look pretty fake.

Unlike a lot of movies, we actually deal stick around to see some stuff after the final death. Doshan and Magnus meet up at the local cemetery. Here the two actors’ thespic limitations reveal themselves as they openly grieve the deaths of pretty much everyone else in the movie. The guy playing Magnus particularly doesn’t benefit from having to ACT! I mean, he’s not laughable or anything, but he was better off underplaying things.

We end the scene with the first of the film’s not exactly astonishing reveals. As Magus leaves the graveyard, he fails to notice the large monument, complete with statue of a woman rising from water, to Jennie Haniver. “Lost at Sea,” it reads, and gives her birthdate as 1701. Gasp! Not a whole more spooky is the fact that the stone offers no date of death.

The final bit involves Magnus leaving the island and consigning his necklace to the ocean depths. Amusing echoes of James Cameron’s Titanic aside, we then dive beneath the waters for locate the turtle one final time. There, in about the least surprising reveal shot in cinema history, we see that the turtle’s shell bears Magnus and Jennie’s initials etched within a heart. Gee, we didn’t see that coming.

Bermuda Depth’s mix of supernatural romance and giant monsters probably won’t be everyone’s cup of tea. Even so, the film was well assembled and holds up quite decently, as do most Movies of the Week from the ‘70s. I hope Warners continues to release these films, and that other studios follow suit. (Universal has started its own DVD-R on demand collection, as well, available exclusively through Amazon.) There are plenty of them out there, and they deserve to be seen and enjoyed again.

Afterward

One of the film’s odder facets is the number of plot threads left dangling after it wraps up. For instance, why exactly does Jennie sometimes appear to doomed men as a child? I mean, clearly in terms of plot mechanics it was to allow for the scenes of her and Magnus frolicking together as kids. It would be nice if the film gave us some sort of internal rationale, however.

Also, why introduce the idea that Magnus’ father was killed by the turtle, or Jennie’s sponsor (or maybe even Jennie herself?) because he’d learned the scientific cause of the abnormal animal growth? The idea that seemingly supernatural beings would fear scientific investigation is interesting—and to me is what marks the beings as being at least marginally Lovecraftian—but it’s a complete throwaway here and serves only to muddle up the general drift of the movie.

Meanwhile, a brief aside establishes that Magnus’ mother drowned the same year his father died. Are we to infer that she too was a victim of the Devil, or whatever malign force is Jennie’s master? It seems like a throwaway line meant to explain Mom’s absence from things, but given the timing and the manner of her death, it remains suggestive.

What exactly is the turtle? Is it the incarnation of Jennie’s master, or merely another servant of it? Jennie seems clearly connected to it in some manner, but we never really get a sense of what’s going on. We do know their eyes glow in identical fashions at one point. And at one point, Magnus spots the turtle swimming in the distance. Running forward to the beach, he finds it gone. However, Jennie is waiting for him in the surf.

Moreover, both the Turtle and Jennie are speared by Eric. (Indeed, if you don’t watch things carefully—especially if you miss seeing Jennie speared in a separate incident—you might suspect that Jennie and the turtle are one and the same. After all, we know she appears in various forms.) Is, again, the turtle the master and Jennie the servant? Do both their eyes glow because…oh, hell, I don’t know.

Some might also look askance at Eric’s seemingly sudden conversion from Caring Nice Guy to Obsessed Ahab Wannabe. However, I don’t see that one necessarily disallows the other. Even so, the transition is rather abrupt, even though it adds to the film’s overall highly tragic feel. By the end of the movie pretty much everyone Magnus loves is dead, except for Jennie, and since he is apparently (sensibly) disinclined to join her, that doesn’t do him much good.

I do like the fact that he doesn’t join her for some inane ‘love conquers all’ ending. Jennie is damned, the occasional romantic escapade or no. Swimming around together while doing the bidding (I guess, maybe) of a huge malign turtle might be fun for the first hundred years or so. However, you’d really have to think looking forward to unending millennia of the same would be a bit of a drag.

Of the main cast, vets Ives and Weathers unsurprisingly fare best. As noted, Ives had won an acting Oscar (Supporting Actor back in 1959), and Weathers had already appeared in Rocky by this time. Neither hams it up, they just occupy their parts in a naturalistic fashion. Still, this is the sort of movie where the supporting actors shine, as the romantic leads are mostly called upon to look pretty.

Speaking of those two, well, they don’t embarrass themselves. This was Sellecca’s first acting gig, and it shows. However, since she’s mostly required to look beautiful and seem mysterious, no strenuous demands were placed on her. In the end she became a capable enough TV star in shows like The Greatest American Hero and Hotel.

Magnus was played by Leigh McClosky. He’s ok—he attended Julliard, where he was Kelsey Grammer’s roommate—although again the scene in the cemetery doesn’t do him any favors. He’s…fine.

Even so, he provides an interesting contrast to Sellecca here. Neither of them sets the world on fire talent wise. That said, whatever that thing is that makes the camera love someone, Sellecca has it and McClosky doesn’t. This was possibly his best lead role, as most of the rest of his resume amounts to a long string of television guest star work. He probably remains best known for playing Mitch Cooper on 46 episodes of Dallas.

Doshan was played by Julie Woodson; this was to be her sole major acting gig. History remembers her best as Miss April, 1973, being Playboy’s third black centrefold model.

She was following in the footsteps of Jennifer Jackson (Miss July 1965) and Jean Bell (Miss October 1969). Bell had a more successful B-movie career, playing such roles as the titular (in more ways than one) TNT Jackson and appearing in Jabootu subject The Klansman.

Ms. Woodson acting career was apparently hurt by her unwillingness to continue stripping for the camera; she walked off the Blaxploitation classic Superfly rather than do a nude scene. Ms. Woodson, who had studied business and sociology at ULCA, retired from acting and worked in construction (!) in her native Kansas.

Bermuda Depths was written and directed by the same men who performed these task on all four of the Rankin/Bass-Tsuburaya coproductions; The Bermuda Depths, The Last Dinosaur, The Ivory Ape and The Bushido Blade.

While Arthur Rankin Jr. provided the stories for this film and The Last Dinosaur, the scripts for all the films were written by William Overgard. Past that, Mr. Overgard basically wrote seven scripts each for the later cartoon series Thunderbirds and Silverhawks.

Director Tsugunobu Kotani likewise helmed the four pictures, taking a ‘Tom Kotani’ credit. Working mostly in Japan, Mr. Kotani directed several other films between 1968 and 2000. During a break from his Rankin/Bass work, he made a film with Pink Lady, the singing duo best known here in the States for the disastrous NBC TV flop Pink Lady and Jeff.