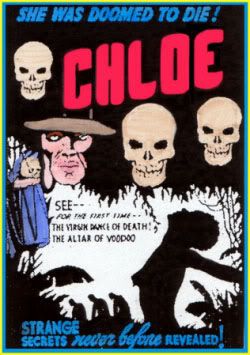

While Mill Creeks’ claim that this 100 movie set is composed of “Horror Classics” is farcical on its face, I can’t deny that man, they’ve really dug up some obscurities. (Largely by stealing them from Alpha and other companies, probably, but hey, public domain.) This is a case in point. In fact, this doesn’t even sound like a horror movie at all.

The IMDB lists a 62 minute running time, but also a 54 minute DVD running time, and that’s exactly what we get here. If this was distributed via road-showing (see below), it’s entirely possible that the other eight minutes consisted of racy material like nudity that got cut based on local standards as the print traveled from town to town. And it’s possible that one of these shortened prints is the one that, somehow, survived all this time. That’s just a guess, but a fairly credible one, I think.

The film opens with footage of each actor, as they are identified with the part they’ll be playing. From this, I start saving up some advance wincing, since there are several black characters in the film. You can’t imagine the movie will be progressive with their portrayal of them. (Although some cheapies from this period, like the Bela Lugosi meller The Invisible Ghost, surprise you on that.) To be fair, though, the black actors get their own onscreen credits, and that’s more than many a big-budget studio film of the period would have given them.

We open with three people going along the Everglades in a canoe. A Nelson Eddy-ish light operetta song plays over the soundtrack (!), and I’ll admit, I didn’t expect that. Since we’re watching the characters in long-shot, I can’t be sure if the guy rowing the boat is supposed to be singing this, although it seems a good bet. Congrats, film, you might be a lot weirder than I’d expected you to be.

We never get an answer to that question, though, so I guess I’ll have to wait and see if anyone breaks into song later in the picture. However, we do eventually get closer to the boat, and meet it’s occupants. These are young Chloe, manly young Jim, and Chloe’s (wince) ol’ black mammy, Mandy.

At one point, Mandy point out the gator the locals call “Ol’ Sambo.” (Wince) Then Mandy bitterly points out the tree from which she says the local white bigwig, The Colonel—sure, what else?—hanged her man. Of course, Jim and Chloe discuss how uppity this all is. (And man, the molasses-thick Southern accents in this thing…)

In case you’re wondering, the entirely nominal ‘horror’ element comes from a voodoo rite later on in the movie. Liz Kingsley might disagree, however, given a scene where one of the actors beats a live snake to death with a stick. And I have to admit, I myself found the Colonel’s smilin’ black valet kind of horrifying myself. Then there’s the scene where a glowering white guy talks to two black guys about horse-whipping. Yikes!

Probably the best part of the film, meanwhile, is an all too short appearance by the Shreveport Home Wreckers as a juke joint blues band. I wonder if they appeared at greater length in the longer cut of the film.

Anyway, the film is really rather more racist than I had expected, and I’m not unacquainted from films from this period. Mandy is a voodoo queen (sure, why not) who raised mixed-blood Chloe. Chloe’s ‘motivation’ is that she’s terminally depressed because, you know, how could any White Man love her, what with the taint and all? Indeed, she literally freaks out at one point when her black blood is alluded to. What a role model.

In Chloe’s oh, so romantic quest for True White Love, Jim doesn’t count. That’s because although he’s clearly played by a white actor, he’s supposed to ‘high yellow’ himself. Thus even the fact that he saves her life at several points apparenlty doesn’t cut it. (And I should note that the film takes Chloe’s side in all this.) Jim’s heroics do lead to an amusing ‘guy fighting a fake / stuffed gator in a swimming pool‘ scene, however.

Luckily, salvation arrives in the form of Wade, a Real White Man, and it’s OK that he loves her because we eventually find out that Chloe is really white too. Whew! Thank goodness!

Certainly in modern eyes, Chloe is a pretty repulsive character, and even many contemporary viewers may have noticed that she doesn’t seem to care very much for the woman and black community who took her into their arms. Indeed, the happy ending is that she gets to escape and go live with proper white folks.

I don’t think it’s going out on a limb here to say the only possible worth to a thing like this is as a time capsule. People who think we haven’t made ANY real progress on racial issues in this country *coughspikeleecough* should give this a look. Things are nowhere near perfect now, but wow, what a difference.

This is also the kind of film that makes me wonder about the mechanics of film distribution back then. In 1934 the studios owned their theaters, which naturally tended to show that studio’s product. Some of the lesser outfits were occasionally hired to provide VERY cheap B movies to go with the studio’s A movies, but probably not enough to keep them in business. I suppose they peddled their wares to independent theaters, basically the grindhouses and drive-ins of their day.

And then there was road-showing, where the filmmaker (or really anybody who had a print of some film in hand) would travel from town to town, renting a local theater for a night and attracting an audience by offering (for the time) unusually salacious material, generally under the guise of it being an ‘educational’ film. Some of these hucksters made a pretty decent buck that way.

Chloe was distributed by Pinnacle Productions*, an outfit that only occasionally put out the odd film, perhaps buying them from local, regional filmmakers. In any case, Chloe was shot in St. Petersburg, Fl, along with another Pinnacle film, Hired Wife. Having been largely dormant for a while, Pinnacle seems to have gone out of business after distributing three pictures that year.

[*Lovers of cinema obscurities can find sets of Pinnacle films over at the Sinister Cinema site.]Actually, a spot of research explains some of this, as well as the aforementioned prominence of the black cast members. It turns out this film may have played the “Chitlin Circuit,” largely segregated theaters that catered to black ticket buyers. These were discretely made productions, in the same way that Spanish films were shot for Spanish-speaking audiences.

A short article on this film can be found at Blackhorrormovies.com. Although the site is fixated on the racism angle in this and its other reviews, it’s still great to have somebody out there gathering together information on obscurities like this. I just wish they put a little more meat in their stews. Better data on Chloe can be found in the IMDB user comments. Several of the commentators seem like people who have researched films of this period, and I learned some stuff.

The best review, though, is here. This guy apparently gave the film a lot more attention than I did, since his review clears up several questions I had while watching it. Warning, though, just in case (for some reason) you wish to see the film yourself, the review is rife with spoilers.

Chloe was played by Olive Borden (yes, she was in fact a cousin of Lizzie Borden), and her story is pretty fascinating. Here’s her mini-bio from the IMDB:

“Olive Borden was beautiful and talented but she became one of Hollywood’s most tragic tales. She came to Hollywood in 1922 with her widowed mother. Olive started her career as a Mack Sennett bathing beauty and was named a Wampas baby star in 1925. She made eleven films at Fox studios where she earned $1,500 a week. Olive became a popular on screen vamp and her jet black hair was her trademark. She hired Jimmie Fiddler as her agent and was nicknamed “The Joy Girl”. Olive lived a lavish lifestyle with limos, mansions, servants, and a dozen fur coats.

In 1927 she left Fox after a salary dispute. She later worked for Columbia and RKO studios. Like many other silent stars she had a hard time making the transition to talkies. Her last film was made in 1934. There were two failed marriages and a broken engagement to actor George O’Brien. During World War II she worked as a nurse. By the age of 41 she was a penniless alcoholic. Her final years were spent in a Los Angeles mission. Sadly many of Olive Borden’s silent films have been lost and this lovely star has been forgotten.”

One wonders if Chloe’s remarkable petulance was intended by the filmmakers, or just a reflection of Ms. Borden dissatisfaction with where her like had taken her. Still, I find it hard to cry for her. $1,500 a week was a hell of a lot of money back in those days. (Hell, I’d swoon if I made anywhere near that much today.) Unfortunately, like many of her peers, she seemed to spend the loot as quickly, or more quickly, than she earned it.

The film’s director, Marshall Neilan, was also a Hollywood big shot in the ’20s, and experienced a similar decline and for similar reasons. He didn’t die so young, however.

As you’d imagine, the print is pretty rough, and the sound is atrocious. After some contrast and brightness futzing, I guess I’d give it a C. Watchable, but maybe only for us old-timers who remember the days of really, really crappy TV broadcasts.

The film is also available on the Alpha disc for The Devil’s Daughter, another Chitlin Circuit voodoo flick. Whether the print is any better, I can’t say.