Quiet, please. This time around the B-Masters go back to the earlier days of cinema, when films had even less words than a Michael Bay movie. Since I wasn’t conversant enough with silent film to know of a really bad one, I went in another direction. (Don’t worry, more traditional suckage will be posted soon.) In any case, when you are ready to move on, click on the above banner to be silently conveyed to the Roundtable supersoaker.

It’s interesting to compare American and European films of the silent era. America was on the rise in the early part of the 20th century, not yet a superpower but becoming one. As such its cinema tended to be boisterous and crudely confident. Even the dreadful poverty of the period, of a sort we can’t even imagine today with our elaborate social safety nets, was viewed as something to endure with grace and good humor, as with the antics of Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp. In American cinema, good guys won.

The films of continental Europe also reflected the mood of the day, and hence were far gloomier and more cynical. There nations seemed perpetually on the brink of war, if not actually at war. Internally, political instability had been a recurrent problem across the continent since the French Revolution more than a century earlier. And indeed, soon after the birth of the cinematic era Europe would be wracked by the greatest war the world had yet known, while bloody revolution and bloodier despotism took hold in Russia.

Both American optimism and European paranoia were invigorated in the wake of World War I. For most Americans, the conflict represented our triumphant debut upon the international stage as a major military power. Here the war fueled the economic and industrial drives that led to the Roaring ’20s. In Europe, however, the scars ran far deeper. Over there, brutal casualties for countries lacking America’s huge population had decimated an entire generation’s finest.

Especially tragic in the long term were the grossly punitive levies laid upon Germany by the Treaty of Versailles. Far surpassing the country’s blame for that war, Germany’s economy was devastated at the very time it struggled to foster a peaceful, democratic government. The financial system would be so demolished that literal wheelbarrows full of cash were used to buy loaves of bread. Such conditions doomed the progressive Weimar Republic and led, as we now know, to some of the greatest horrors the human race has known.

From the rubble of the collapsed Weimar regime arose a toxic combination of German economic disintegration and burgeoning rage and resentment at its treatment following the Great War. This was met by willful fecklessness on the part of the war’s European victors, who vainly sought to avoid a second conflagration by turning a blind eye to the rise of the Nazi party and Germany’s increasingly aggressive (and by treaty, illegal) rearmament. Nor did the earlier establishment of a revolutionary communist regime in Russia calm the continental imagination.

During this same period, however, America remained largely untouched by such turbulance. The end of WWI heralded a new golden age, one that lasted until the stock market crashes of the 1929. Things were far different in Europe, where the clouds of war quickly reformed and grew ever more ominous.

As such, in direct counterpoint to America’s far sunnier films, Europe’s cinema culture was far darker (as well as, it should be noted, more sophisticated). America even then tended to celebrate in its arts heroes, or even superheroes. In European arts, however, villains and supervillains were at least as often at the center of things. These malevolent figures committed grand crimes and schemes not merely for petty monetary gain, but to trigger complete political collapse and anarchy. Even when Good triumphed, an enduring atmosphere of dire economic and political fragility was fostered.*

[*Culturally, American film wouldn’t experience this level of paranoia and cynicism until the advent of the science fiction and film noir genres in the ’50s.]In the years immediately before World War I, France detailed in both literature and films the archcriminal Fantomas. Fantomas was a murderous master of disguise and intrigue, along the lines of Sherlock Holmes’ nemesis Prof. Moriarty. Although, as the protagonist of his own series, Fantomas was arguably more like the direct obverse of the Great Detective himself.

Borrowed from a popular series of pulp novels, Fantomas became the subject of several outlandish serials directed by Louis Feuillade. Feuillade was also responsible for the equally influential adventures of sultry villainess Irma Vep in the ten-chapter serial Les Vampires (1915). Both Vep (with the help of various criminal organizations) and Fantomas, who starred in five Feuillade serials beginning in 1913, committed crimes so dire that they threatened nothing less than the very existence of several European states.

After the war, however, cinematic paranoia became the special province of German filmmakers. As soon as 1920, director Robert Weine made the expressionist classic The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. At its climax, the film boldly revealed the murderous Caligari to be an authority figure preying upon the very people placed in his charge. This revelation proved entirely too bold, the metaphor for the dangers of totalitarian government too obvious. Weine was forced by his producers to alter the ending, whereupon the villainous Caligari is miraculously transformed into a benign authority figure who vows to cure the picture’s (now) insane protagonist.

Before settling on Weine, Caligari’s producers had sought to engage the services of fellow expressionist director Fritz Lang. Lang, for his part, would ultimately adopt Caligari‘s (original) themes and pursue them so diligently that he was forced to flee Germany rather than become a propaganda tool for the Nazis. Lang’s wife and co-worker Thea von Harbou (she co-wrote this movie, in fact), in fact, stayed behind and did just that.

Contemporaneously with Caligari, Lang was already making paranoid dramas like The Spiders, an Indiana Jones-esque adventure featuring yet another super-criminal organization, and the brilliant espionage story Spies. Several years later he offered Metropolis (1927), another film centered upon a megalomaniacal supervillain who sought to control an entire populace. That film’s antagonist employed super-science to further his schemes, which became also the hallmark of, arguably, Lang’s greatest creation.

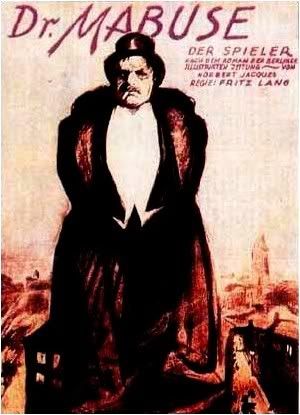

For it was Lang who brought to the screen the adventures of cinema’s most vital and enduring supervillain, the outlandishly brilliant and seemingly indestructible Dr. Mabuse (Mah-BOO-zah). Mabuse far outstripped Fantomas, engaging in schemes seemingly intended to destroy civilization itself, and possessing literally superhuman mental powers. Mabuse’s psyche was so powerful that even after his death [re: Lang’s 1933 sequel, The Testament of Dr. Mabuse], he was able to colonize another man’s mind by dint of his writings. As a result, he was basically able to reincorporate himself in another body, through what amounted to a fantastic Nietzschean triumph of pure will.

Yet we get ahead of ourselves. The good Doctor’s screen adventures began with our present subject, Lang’s 1922 drama Dr. Mabuse the Gambler. Running a robust four and a half hours,* the film was split into two component chapters. Eleven years later, the villain returned to the screen in the previously alluded to The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933). Amusingly, this revealed that Mabuse existed in the same world as Peter Lorre’s psychopathic killer from Lang’s then recent masterwork M (1931). M’s protagonist, the lumpen but wily Inspector Lohmann, was to be Mabuse’s antagonist in that later film.

[*Lang was much enamored of the long form, as indicated by the just recently discovered three and a half hour director’s cut of Metropolis.]Following The Testament of Dr. Mabuse, Lang stole from Germany and eventually settled in America, where he pursued his directorial career and made many explicitly anti-Nazi films both before and during the war. In 1960, however, Lang finally returned to (West) Germany and made one final film. This, fittingly, was The 1,000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse. That this was intended as a remake/update of the earlier films is indicated by the reincarnation of Inspector Lohmann in the burly form of Gert “Goldfinger” Frobe, a quite accurate doppelganger for the role’s previous inhabitant, Otto Wernicki.

The 1,000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse was successful enough that it in turn kicked off an increasingly campy and junky series of Mabuse flicks in the years to follow. Especially notable in this run was a remake of The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1962), which featured Frobe’s third and final turn as Lohmann. This makes the Inspector the rare character to appear in five different films in the guise of two different actors, and over a span of thirty-one years.

Camp was huge in Europe during the ’60s, and many supervillains hit the screen there, from veterans such as Mabuse, Fantomas and Fu Manchu to newcomers like Diabolik and Satanik. Sadly, though, many of the original German versions of these later Mabuse films have ceased to exist. As a result, several of the movies are not available at all, and others are available only via their altered and dubbed (and usually heavily worn) English language versions.

Before we begin examining the four and a half hour Dr. Mabuse the Gambler proper, let me further explain that the film is available via two different editions. A DVD set released by Image back in 2001 offers a version of the movie 40 minutes shorter than its full length. In compensation, however, it also features a wonderfully incisive commentary track by Mabuse scholar David Kalat.

Mr. Kalat is the author of several terrific film books, including The Strange Case of Dr. Mabuse, as published by the essential McFarland Press. Mr. Kalat continues to offer wonderful commentaries on the discs for many noir films and other genre pictures, including those for several Godzilla movies as released by Classic Media. As for his Dr. Mabuse the Gambler commentary, one of three he did for various Mabuse discs, many feel it to be one of the very best film commentaries ever.

Kalat is enough of a Mabuse enthusiast that he actually started his own DVD label, All Day, to release the restored German versions of The 1,000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960) and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1962). Meanwhile, a restored version of the German language version of Lang’s original 1933 The Testament of Dr. Mabuse was subsequently released by Criterion with Kalat’s input, a set that also offered Lang’s simultaneously helmed French language version of the film shot with French actors…my head hurts.*

[*For the record, Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse is the German version, while Le Testament du Dr. Mabuse is the French one. Again, both are included on the Criterion set.]Here’s where it gets confusing. Well, more confusing. The earlier All Day disc for the 1962 Testament remake includes as an extra the entire American dub version, released here as The Crimes of Dr. Mabuse, of Lang’s 1933 German original. I actually corresponded with Kalat at the time the All Day discs were coming out. I inquired as to the lack of notice regarding the inclusion of the original (albeit Americanized) version of the film on the remake’s DVD.

He replied that since the presentation wasn’t up to snuff in his opinion, he would have felt he was leading people on by proclaiming it loudly on the box art or advertising materials. To this day, it thus remains the greatest and most satisfying surprise extra I’ve found on any of the hundreds of DVDs I’ve purchased.

Thus, if you’re following all this, you can actually buy three versions of the 1932 The Testament of Dr. Mabuse: the American dub as found on the All Day disc for the 1962 remake; the restored German version featured on the Criterion set, and as an extra on that latter package, the concurrently shot French version of the film. Whew! Happily, the Criterion Testament DVD set includes as another extra a comparison between the German, French and English dub versions.

For what it’s worth, all these various discs are still available. Buying the whole of them is an expensive proposition, however; around one hundred and fifty smackers for the five DVDs editions I’ve mentioned here. Only Amazon, for instance, has the two All Day discs still available—and they only have a couple of each left—and they will set you back nearly $30 a pop. Even so, they are all essential, really, and happily they all came out during a time when my DVD budget was *far* higher. Thus all of them happily sit together upon my DVD shelves, no doubt scheming my ruination.

Finally, let’s return to the two editions for our current subject. The casual Mabuse fan (if there is such a thing) should probably stick with the Kino disc. This features the full cut of the movie, 40 minutes longer than that found on the Image DVD. And, frankly, the picture quality is much higher. On the other hand, if you’re anal enough (as I was), you may wish to procure both the Kino and the truncated (if still lengthy) Image editions, allowing one to watch the actual full film on the Kino disc while also enjoying Kalat’s renowned commentary from the other.

As noted, the entire Dr. Mabuse der Spieler (a.k.a. Dr. Mabuse the Gambler) runs a heartily Teutonic four and a half hours. Given this, is it normally split into two discrete films, presumably to facilitate showings on consecutive evenings. The first chapter runs two and a half hours itself and is subtitled The Great Gambler A Picture of Our Time. The second part is more action-packed, running a bit under two hours and subheaded Inferno: A Play of People of Our Time.

Having come to the series from the ass-end, and in sitting down to watch Dr. Mabuse the Gambler for the first time, I was most struck by the differences between the Dr. Mabuse seen here and the one I had come to know from his later cinematic adventures. Most tellingly, this picture opens on Mabuse, who uniquely remains a nearly constant onscreen presence throughout. In contrast, the Mabuse of the later films is a shadowy figure who issues orders to his various henchmen while hidden behind a screen or some such. Any underling foolish enough to try to actually glimpse Mabuse is instantly liquidated.

Thus removed from even the audience’s gaze, Mabuse is seemingly transformed into something other than fully human. Here, on the other hand, he is clearly a man, if an admittedly evil, even devilish, one. The difference is stark, akin to picking up on a series of novels written in the third person, only to backtrack and find the first book was written in the first person singular.

Mabuse is first seen rifling through a stack of photographs which depict the myriad disguises and identities he employs for his undercover work. He then shuffles these like a deck of cards, no doubt to further the image of him as a ‘gambler.’ (Albeit the sort of gambler who always fixes the game). From this he then randomly chooses his next identity.

Mabuse remains a master of disguise in the later films, but again this is meant to reinforce the suggestion that he is more an abstract mental construct than an actual person. As noted above, even after his death Mabuse is able to impose his consciousness over that of another, purely through his writings. A neat, one might say almost Lovecraftian idea.*

[*The scene where his victim is psychically annihilated is played like a ghost possession scene. In a classical sense, ghost stories generally involve an element of doubt as to whether supernatural forces are driving events or simple insanity. See the original The Haunting and The Innocents for cinematic examples. Aptly, this holds true here as well. Was the victim actually possessed by the shade of Mabuse, or was he merely driven insane by Mabuse’s writings and imagined himself possessed?]In this film, however, Mabuse is concretely a man. This suggests, perhaps, that Mabuse was a more conventionally Moriarty-esque figure in the source novel by Norbert Jacques. Most tellingly, Mabuse is actually a public figure in this film. A well-known psychoanalyst, we see him giving a well-attended lecture on the subject. It’s notable that psychiatry was in its infancy when this film was made, and its legitimacy as a science rather less established. Indeed, Mabuse’s mastery of the mind goes well beyond science, as we’ll soon see; almost into sorcery.

Moriarty himself, as more greatly befits the stolid British temperament, was a professor of mathematics. And if Moriarty arguably edges into supervillainy, Mabuse—especially in his later adventures—leaps boldly into it. In this Mabuse again accurately reflects the generally more outré continental imagination.* I assume the eventual freeing of Mabuse from mortal constraint represents Lang taking the character and remolding him to suit his own purposes.

[*Dr. Fu Manchu, it is true, was created by a British writer. Naturally, however, the villain himself was a foreigner, and a mysterious, inscrutable Oriental to boot.]Increasingly obsessed with destroying nations themselves, Mabuse becomes less a simple criminal and more a threat to civilization itself. To the extent that Mabuse remains a Moriarty-like nemesis figure, he would more properly be one for Sherlock Holmes’s brother Mycroft. Sherlock Holmes battles injustice, but Mycroft’s purview is the safety of the Crown itself. The Great Detectives himself suggests that, at certain times, Mycroft “is the British government.”

In furtherance of this theme, when Lang assigns Mabuse an arch-nemesis, it’s not a private adventurer like Sherlock Holmes or Nayland Smith, but instead representatives of the government. In this initial film, the doctor is opposed by state prosecutor von Welk, and Mabuse’s later serial antagonist is the idiosyncratic and dogged police Inspector Lohmann.* Although an impressive individual, Lohmann (again first introduced in Lang’s M) casts as larger shadow by dint of his government credentials, which lend him the authority and power necessary to counterbalance the nearly superhuman Mabuse.

[*In the ’60s, as the series continued to degrade, eventually another protagonist was introduced in the person of FBI agent Joe Como. Presumably meant to heighten the films’ commercial appeal in the States, the oft lunkheaded Como was played by American actor Lex Barker. He was a far less canny figure than Lohmann, although by that point Mabuse was also a mere shadow of his former self.]Indeed, even in M, Lohmann not only contends with finding the titular child killer, but does so in opposition to the entire organized German underworld, which seeks to eliminate the murderer themselves. This underworld is run by what amounts to an executive board of criminals. Fittingly, this occurs towards the tail end of Mabuse’s eleven year absence from the scene. It’s intriguing to theorize that it was the power vacuum created when Lohmann broke up this criminal organization which allowed for Mabuse’s reemergence just a few years later.

In pitting himself against not only Mabuse but the very legions of the criminal underworld, Lohmann is indeed a Mycroft Holmes figure. Brilliant, yes, but his abilities are far magnified by having the weight of society and order behind them. Per tradition, of course, as the hero Lohmann also works under several limitations which don’t constrain the villain. Lohmann must operate under appropriate police regulations, for instance. And while in abstract theory he has the entire government and populace behind him, most of the time his available forces number far fewer than the veritable army of men at Mabuse’s disposal.

Lohmann’s greatest advantage, probably, is that he operates in the field himself. By the time the two come into conflict, Mabuse has entered his ‘shadowy figure’ phase, and must work at an imperfect remove through his men. This protects him from direct counterattack against his person, but also lends Lohmann more flexibility.

In this initial film, however, we find Mabuse in his formative stage, one in which he still oversees his operations in person. Even so, many of his other signature traits are already manifest. First is his ruthless demand for complete obedience to, and observance of, his orders. As the execution of his elaborate plans often necessitates split-second timing, Mabuse requires his operatives to be precisely where and to act exactly as he commands.

For instance, the initial step of the first multi-stage scheme we witness involves a henchman assaulting (but not killing) a courier in a railway car. Seizing the man’s briefcase, which contains a secret commercial contract, the miscreant tosses it out the window of the train just as it passes over an underpass. Down below, another henchman drives past in an open car, with timing so precise that the briefcase lands in the backseat as the vehicle speeds along. Ironically, Mabuse uses the predictable efficiency of the German rail system itself as a weapon in his arsenal.

Once he has the contract in hand, Mabuse dons another disguise and takes another formation of underlings to the stock exchange. The sudden announcement of the lost contract plunges the stock of the concerned company, for should the information contained within be made public it will negate the deal. Mabuse, standing upon a table and overseeing the resulting hysteria from a seemingly god-like vantage, waits until the stock falls to a small fraction of its former worth before announcing he will buy.

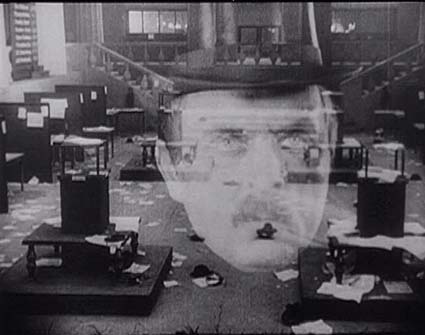

After buying from panicked sellers, and in accordance with his plans, a second announcement is made. The briefcase has been found, and the contract apparently unmolested. At this the stock’s value skyrockets back up, leaving Mabuse many times the richer. We cut ahead to a shot of the now empty but seemingly devastated and trash-strewn chamber. Over this forlorn tableau is superimposed the visage of Mabuse, the author of so many’s ruination. (We soon learn that Mabuse also runs a counterfeiting organization. As with his actions here, this not only provides him with greater resources, but simultaneously strikes a significant blow against the nation’s financial integrity.)

During the course of this scheme, we see messages passed from one operative to another via elaborate methods. A beggar, sans a leg presumably lost in the Great War, approaches a disguised Mabuse in the street. He is given a donation, on which are written instructions. Another man later starts a row with a woman doing her knitting as she sits on the stoop of a poverty-stricken tenement. She chucks a ball of yarn at him, which proves to contain a key he unobtrusively palms.

From such battered souls Mabuse constructs much of his malignant army, a guerilla force that remains undetected because they, as Mao would later observe, “swim in the sea of the people.”* In essence, and I don’t want to overplay this aspect, but it’s hard to ignore the similarities between Mabuse’s disenfranchised followers here and those initially accrued by Hitler and the National Socialists not so many years afterward.

[*On the other hand, Sherlock Holmes employed similar logic. The omnipresence of poor people renders them invisible to observers. Hence Holmes’ employment of street urchins as operatives, an assembly ex-military man Watson whimsically dubbed the Baker Street Irregulars.]As you might gather from the length of the film, Dr. Mabuse the Gambler is rather episodic in nature. Broken down into a series of acts, it’s not altogether different from the multi-chapter serial Les Vampires. Thus, with the stock market scam concluded, we now move on to Mabuse’s next scheme. This sees him (once more disguised, naturally) attending a decadent nightclub for the idle rich. Among such moral and intellectual weaklings Mabuse swims like a shark among goldfish.

We see a bit of a (ludicrously bad) racy stage show starring dancer Cara Carozza, who is the town’s latest sensation. All are entranced by her save Mabuse, who has eyes only for his next victim. Here I was rather startled to learn that Mabuse’s mental powers are so great that they amount to telepathy.* We watch as he culls a callow youth named Hull and apparently mesmerizes him from a distance.

[*Since Mabuse seldom comes into direct contact with people in the later films, this aspect of his powers doesn’t much come into play. Here, however, it seems to tie Mabuse in with his fellow mesmeric psychiatrist Dr. Caligari. Indeed, most of the supervillains of the time exhibited hypnotic abilities.]With Hull in his hand, Mabuse is escorted to an exclusive men’s club of which the young fellow is a member. Entering as a guest in this fashion renders him instantly reputable to the other wealthy, socially-connected members. Thus again does Mabuse masterfully exploit the weaknesses of the society about him.

At the club, the disguised Mabuse is soon engaging his feckless, naive host in a card game. Unsurprisingly, Hull’s losses mount up quickly, and are large enough to draw comment from his peers, who presumably have been known to casually drop huge sums of money themselves. Eventually the staff actually suggests to Hull that he stop playing, but he remains in Mabuse’s power and continues. And so the hours pass.

Morning arrives before Mabuse takes his leave, Hull’s IOUs in his pocket. Only now does Hull begin to rouse, as if from a dream. His fellow club members are amazed to learn that the irate Hull now claims no knowledge of the man he lost to, a man he doesn’t even remember having brought into the club himself. Most extraordinary is that Hull’s last set of cards, which he had proclaimed a losing hand, now lies open upon the table and is, in fact, a winning one.

Previously that same evening, Cara, the dancer, had received a note of instructions from Mabuse. Her reaction to finding his note—fleetingly downbeat but otherwise ecstatic—indicates that she is in romantic or sexual thrall to Mabuse, to some extent unwillingly, but beyond her ability to control, like a drug habit. This woman is the toast of the town, an intense object of desire of the country’s wealthiest young men. Even so, she has ceded all this power in turn to Mabuse.

She learns that a hotel room has been reserved for her. This is next to the room where Hull has been told to meet ‘Balling’ (the identity he assumed during all this) and pay off his IOUs. There she will presumably be used in one of the Dr.’s blackmail schemes. We see how fluid Mabuse’s methods are, elaborate master schemes built in layers of smaller steps.

Mabuse’s army is composed the same way. Some of his workers are career criminals, glad to be putting their skills in the service of such an overlord. Some are people from various classes who work either willingly or unwillingly for Mabuse, victims of blackmail or those receiving bribes. Others are the disenfranchised, content with a bit of money and perhaps a chance to strike back at a society that’s failed them. For all of them, one rule holds constant: Once they are ensnared in Mabuse’s web, there is no escape save death.

At this point we have concluded the second act, and are about forty minutes in with roughly four hours remaining. Now that we’ve gotten a sense of who Mabuse is and how he operates, I will cease to track events in such detail. After all, I wouldn’t wish to ruin the movie for anyone. I will say that I hope adventurous souls are not scared away by the film’s lengthy running time. Although brutally sluggish pacing is a regular attribute of silent film, such is not a problem here. Lang keeps things moving quite well, and time passes pretty effortlessly.

In any case, the gulling of Hull was predictably but the first step in a much more elaborate plot. Cara is duly employed to throw herself at the fellow (their brief romantic antics, false as they are on her end, remain the film’s only wince-inducing element) and act as Mabuse’s spy. Meanwhile, though, we meet our protagonist, State Prosecutor von Wenk.

As things progress, I was again struck by how comparatively conventional this first film is. Mabuse truly is more a standard supervillain like Fantomas or Irma Vep, and hence has been assigned a rather traditional adversary in Wenk. Our Hero is a rather stolid figure, certainly less amusing and interesting than the captivating Inspector Lohmann. I guess with Mabuse actually onscreen so much, you don’t require as interesting of a hero to hold your attention. That doesn’t mean it wouldn’t have been nice, however.

Aside from being a bit of a stiff, Wenk is also right out of central casting. As is standard in the supervillain serials of the time, Wenk fights back against Mabuse by mirroring his own tactics: Donning disguises, running his own scams, etc. Most tellingly, he recruits Countess Dusy Told to be a female agent of his own, an analogue for Mabuse’s use of Cara. Ironically, the Countess feels morally compromised in this role and soon abandons it.

Still, at first Wenk’s relationship with the Countess seems the more promising. He appears to consider her to be an ally, rather than a mere tool. When the besotted Cara warns Mabuse to beware Wenk’s interference, the Doctor laughs with megalomaniacal disdain. The lesson Mabuse presumably will learn at Wenk’s hand must have been a bitter one. Never again would he expose himself as recklessly as he does here.

Let me be clear; I don’t wish to sound like I’m disappointed in the film in any way. Despite any qualms I express as to Mabuse’s rudimentary conception here, I’m in no way arguing that this film is in any way unenjoyable. Quite the opposite, in fact. Any picture that can hold one’s interest for nearly five straight hours must be doing an awful lot of things right.

As one would expect, the movie’s primary strength is that it was directed by one of the world’s great filmmakers. Lang’s provocative early mastery of montage and expressionism is to be expected. Even so, the power of his imagery remains astounding. The scene where Mabuse first meets an equally disguised Wenk over a card table and attempts to bend him to his mesmeric will is quite simply incredible stuff. I was actually left mourning the fact that I wasn’t experiencing the sequence for the first time in a theater, where it could have worked its full power upon me.

This and another scene where Wenk is imperiled also make canny use of animation, as Mabuse’s words seem to materialize and dance before Wenk’s befuddled eyes. Again, this is just masterful stuff.

Even so, it remains true that the film lacks many of the qualities that would define Mabuse in the decades to follow. My cinephile annoyance at coming to the character’s first chapter late in the game has begun to fade. This is not the Mabuse that I became such a huge fan of, and I indeed may have been better off catching his later adventures first. Maybe.

Comparisons of apples and oranges aside, the picture remains interesting and entertaining on its own terms. The epic length passes without much clock-checking, and rarely did I lean on the fast forward button. The pacing of silents can be so slow that I have had recourse to such in the past, finding that for many films playing them at double speed makes them entirely more watchable.* Here I had little need of such expediency. Once again the rule is confirmed: A good long movie seems shorter than a boring short one.

[*Yes, I realize this makes me a bit of a barbarian. However, this technique works perfectly well with DVD, as the image’s digital clarity remains entirely intact. All you really lose is the ability to hear the musical score.]As we close out part one of the film, things take a turn for the (even more) melodramatic when Mabuse suddenly evinces a passion for the Countess and kidnaps her. Up to now, Mabuse has more or less seemed like a more typical gangland boss. Enflamed by his new feelings, however, he for the first time sounds like the Mabuse to come: “Only now shall the world know who I am! I…Mabuse! I want to become a giant, a titan, churning up laws and gods like withered leaves.”

The metamorphosis isn’t complete, however. Not until (presumably) he has lost all due to his human lust for the Countess will Mabuse finally shed his remaining humanity and become something like the sheer, nearly metaphysical mental force seen later. He must still cast off his remaining shreds of humanity before becoming the Nietzschean superman, beyond all conventional notions of good and evil, and that he is destined to become.

Before that occurs, however, these tatters of human weakness leave him exposed and vulnerable. It is actually startling to see Mabuse reduced to drunkenly raving to his equally soused henchmen. Worse, absconding with the Countess in his own guise finally begins to establish a clear trail for Wenk to follow. Even Mabuse himself recognizes the danger. He later confesses to the Countess, “I haven’t been the same since I met you. I’ve been making mistakes.” So compromised does Mabuse feel himself to be that he plans to flee the country and set up shop elsewhere.

Even so, Wenk remains unable to take advantage of this. Bodies begin piling up all over the place, each time thwarting Wenk just as he believes Mabuse to be in his grasp. Wenk’s only real advantage is that he continuously manages to survive Mabuse’s assassination attempts. (Oddly, Mabuse at one point has Wenk completely in his power and lets him go. Yet in the very next scene we find him demanding Wenk be immediately killed off. I don’t really follow what’s going on here. Maybe Kalat’s commentary will hash it out.)

Eventually Wenk determines that the villain is Mabuse and besieges his house with cops and, eventually, the military. This after Mabuse and his gang kick off a huge gunfight from inside their fortress.* This scene is one that Alfred Hitchcock must have seen before he shot his extremely similar climax for 1934’s The Man Who Knew Too Much. (Thanks to Sandy Petersen I just recently saw that film for the first time, and thus was able to make the connection.) Certainly Lang’s stock would have risen greatly by then following the release of M, making it quite likely Hitchcock would have seen his stuff.

[Such gun battle-oriented sieges were kind of a motif for Lang. Similar episodes occur in Spies—an essential watch for Mabuse buffs—and 1933’s The Testament of Dr. Mabuse.]Mabuse temporarily escapes, but eventually finds himself trapped like a rat and suffers a complete mental breakdown. (His hair now wildly unkempt and dead white, the maddened Mabuse greatly resembles fellow lunatics Dr. Caligari and Metropolis‘ insane techocrat Rotwang, a role also played by Mabuse portrayer Rudolf Klein-Rogge.) On its own, this climax would seem a standard bit of irony. However, given Mabuse’s return eleven years later, in retrospect it’s more like a caterpillar entering its cocoon.

This is probably where the first film’s utility is greatest. Standing alone, this is a standard tale of a villain who dares all and learns that crime does not pay. In conjunction with the next film, though, even with the decade-plus separating them–perhaps especially with the decade-plus gap between them–it becomes an epic saga that makes George Lucas’ vision of how Anakin Skywalker became Darth Vader look even more feeble by comparison. Assuming that was possible.

If Mabuse’s parallels to the rise of Hitler and fascism in Germany are necessarily abstract in this film, they were much more concrete in The Testament of Dr. Mabuse. Lang actually gave Mabuse National Socialist rhetoric to declaim. Most telling to me, however, is that Mabuse’s institutionalization in fact allows him the time to transform himself into the creature we generally know him to be. He goes in apparently shattered, but reemerges more powerful than ever.

This strikes me as similar–perhaps purposely–to Hitler’s nine month imprisonment (!) for treason in 1924. Many in the Weimar establishment hoped that Hitler’s time in prison would reduce him politically. Sadly, this proved not to be the case. Like many to follow, these officials also sought to assuage Hitler by making his time in prison as easy as possible. Freed from having to do labor and exercising full visitation rights, Hitler instead used his vacation at state expense to compose his tract “Mein Kampf” and refine his political aims and tactics. After that, the die was cast.

Given Lang’s following of Hitler and antipathy to his rise to power, it’s hardly unthinkable that such was not on Lang’s mind when he returned Mabuse to the screen in 1933. But that, of course, is a tale for another time….

Speaking of the return of super-geniuses, a tip of the homberg to Carl Fink for his typically masterful vetting of the above review.