Posted inReviews

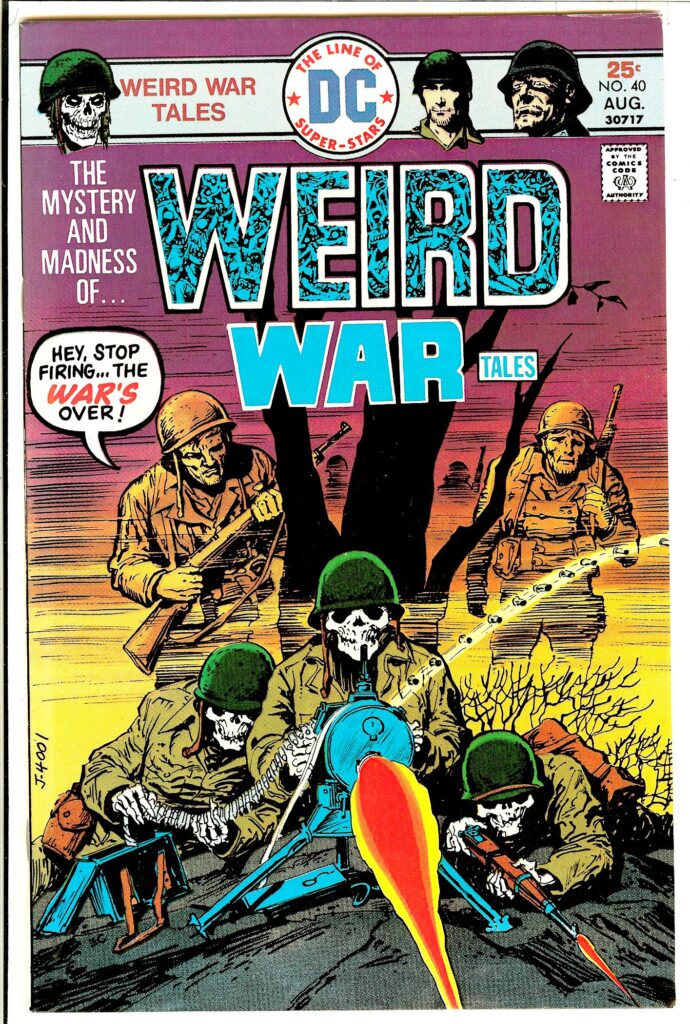

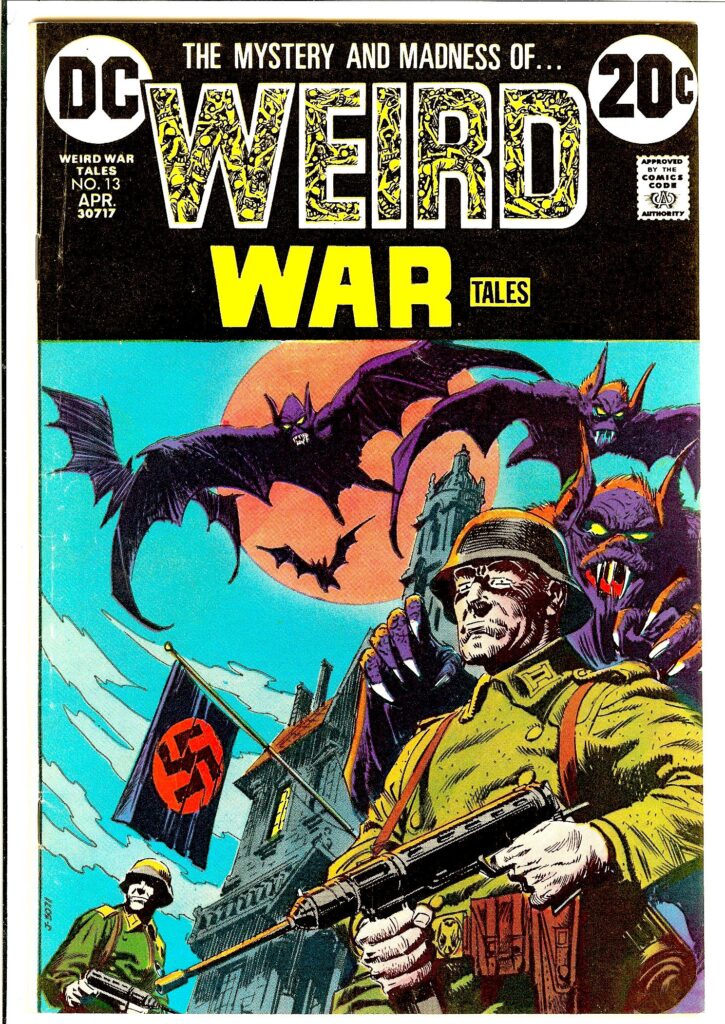

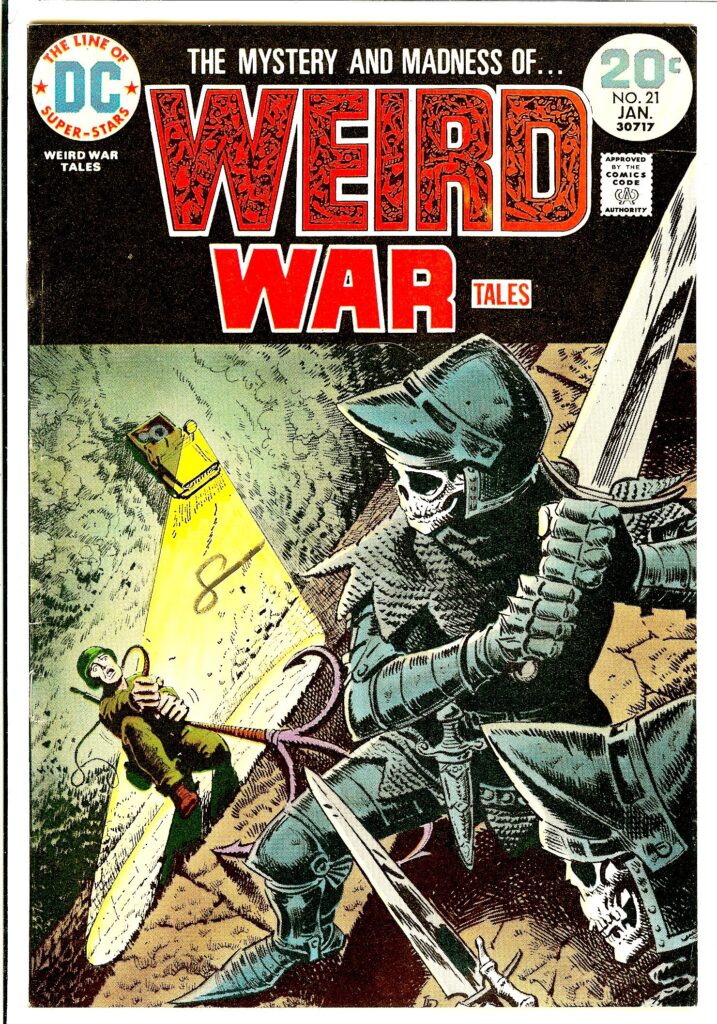

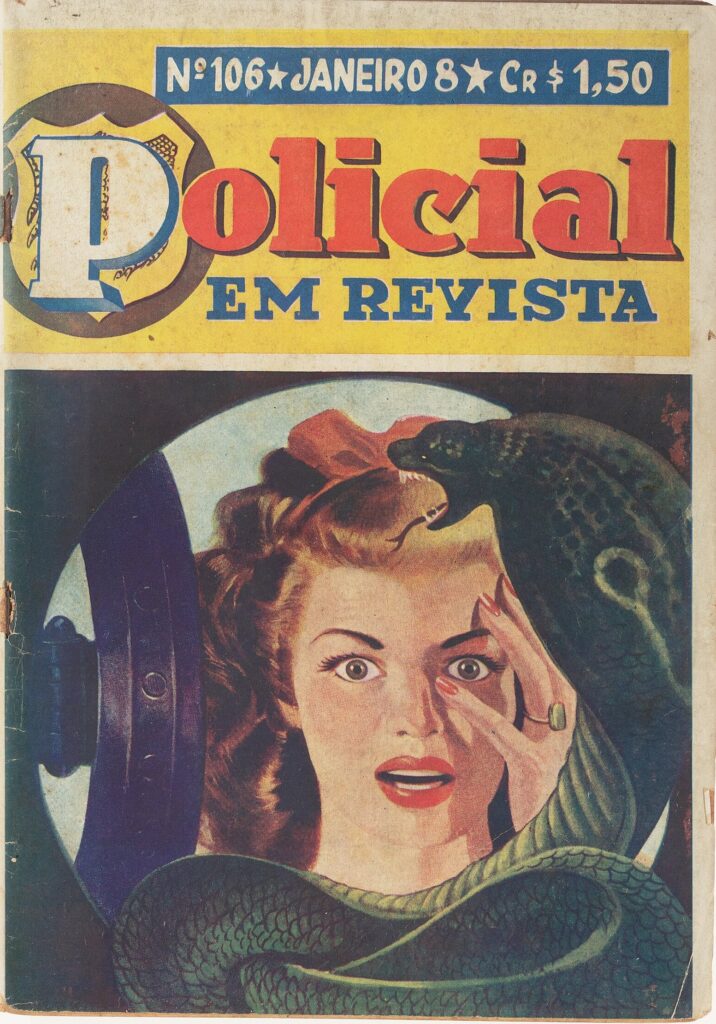

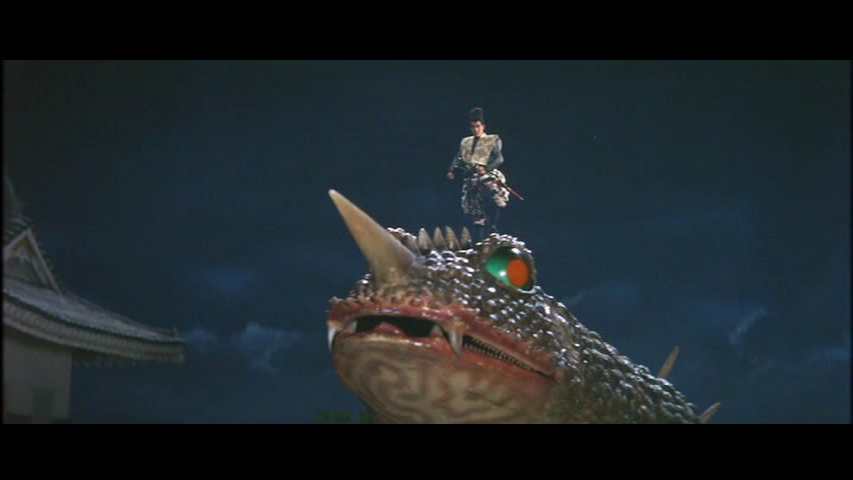

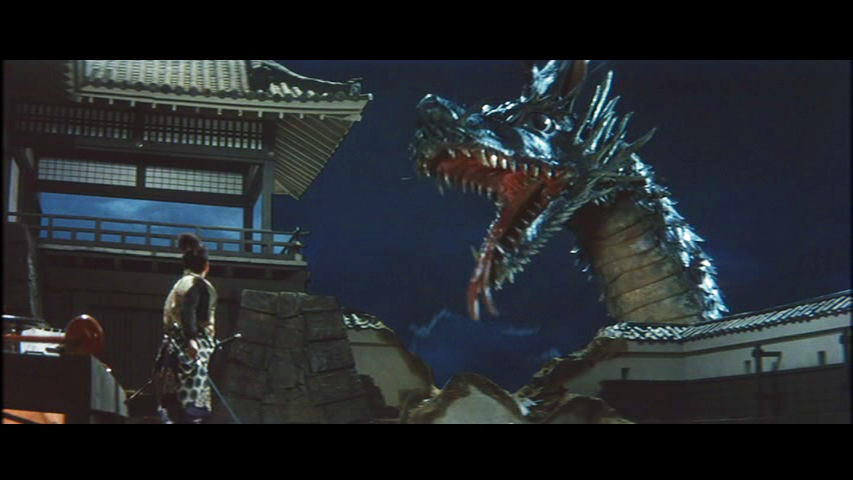

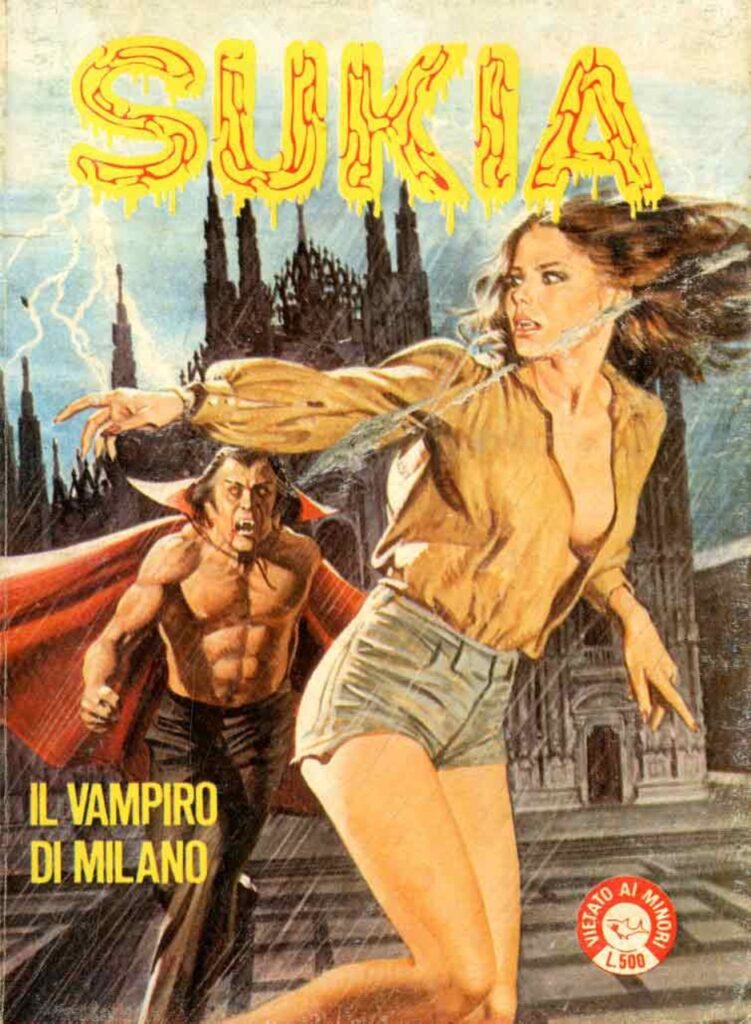

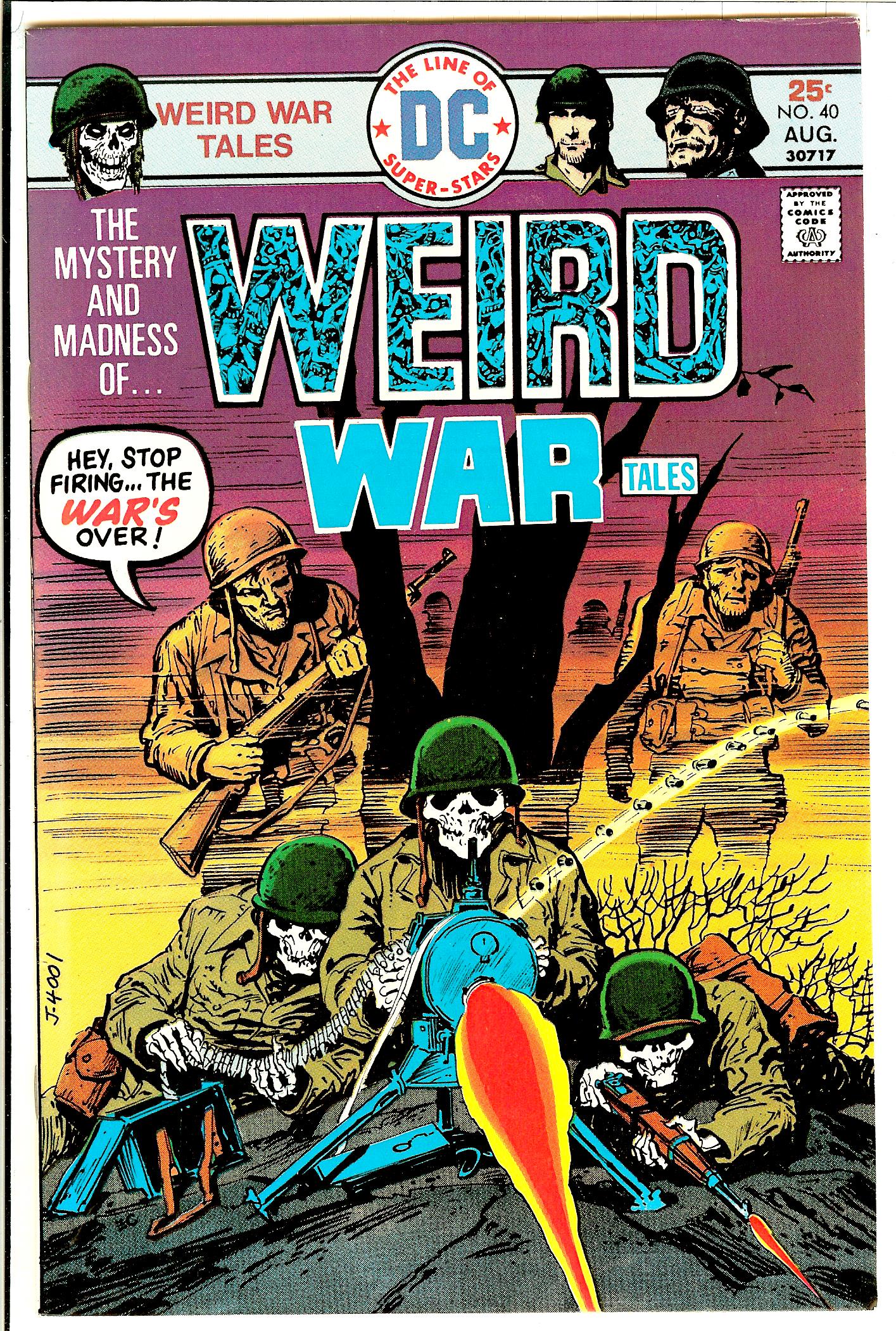

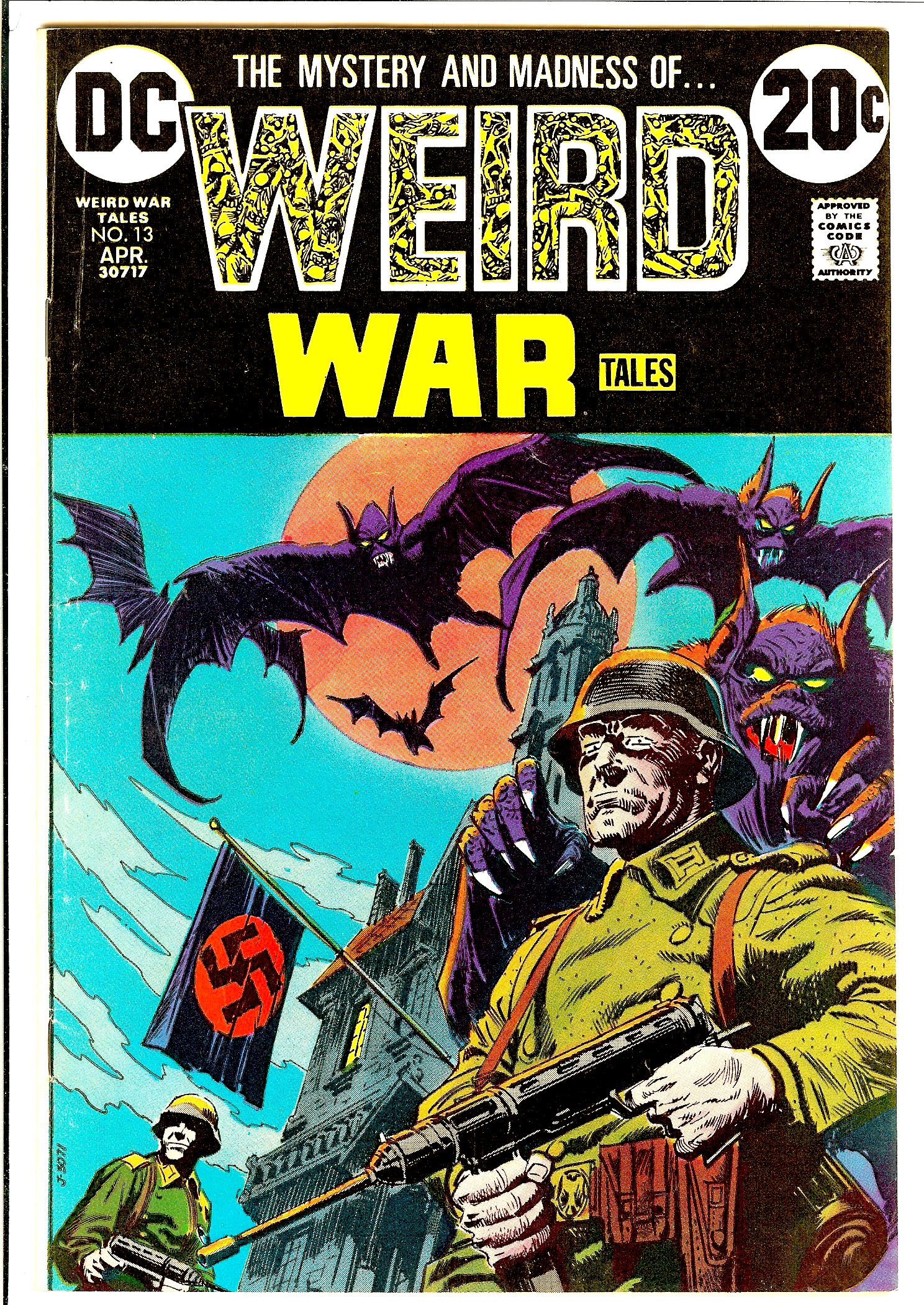

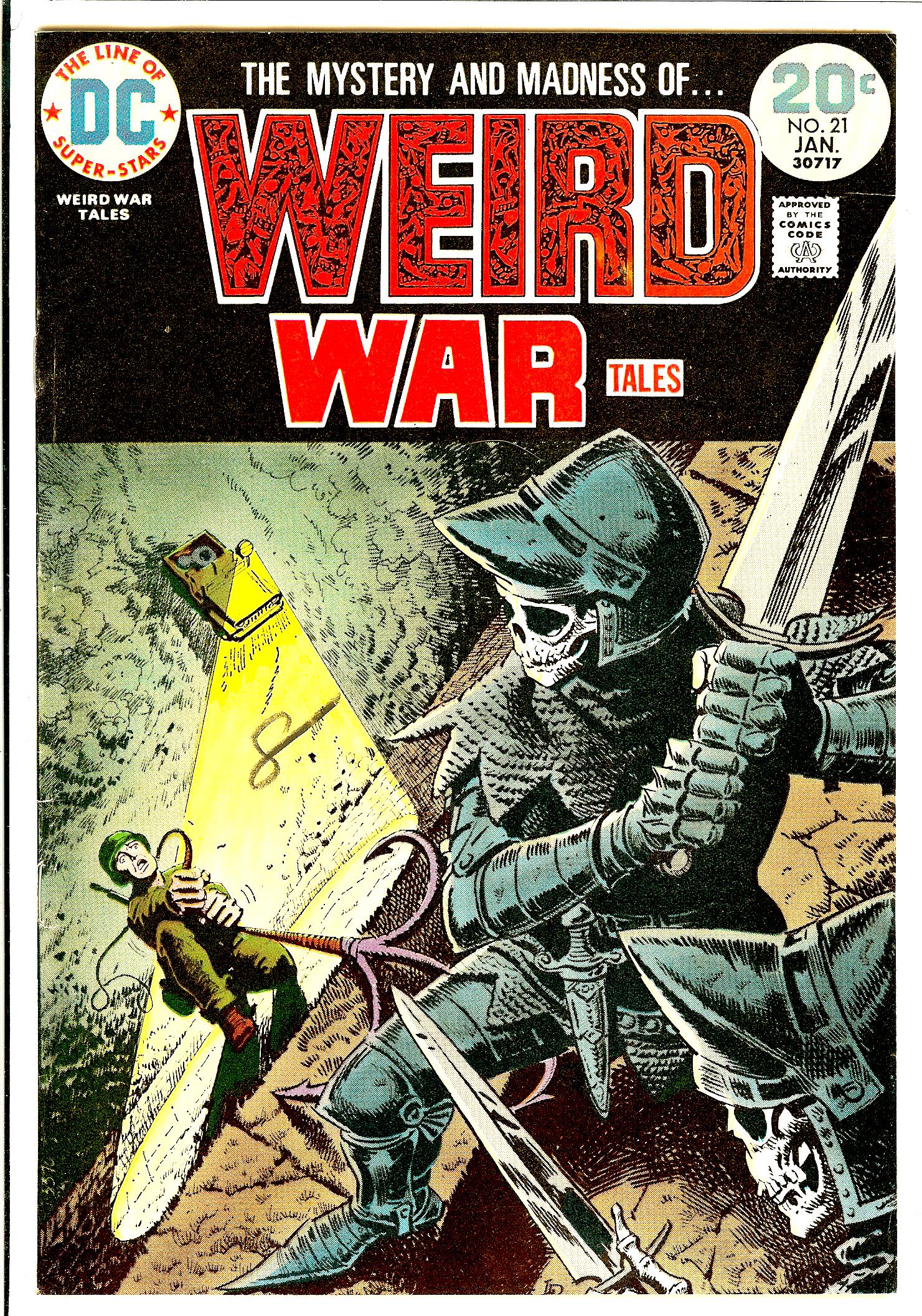

Monster of the Day #3860

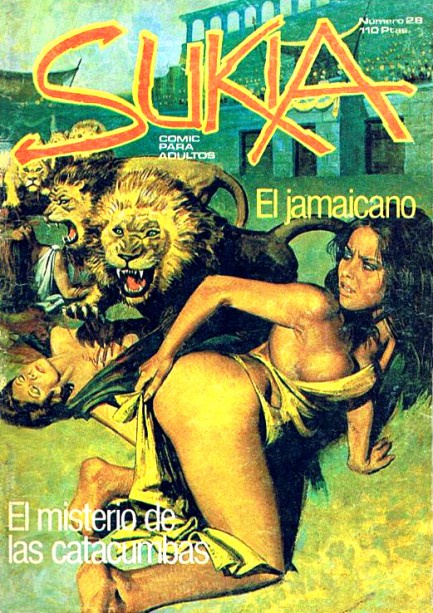

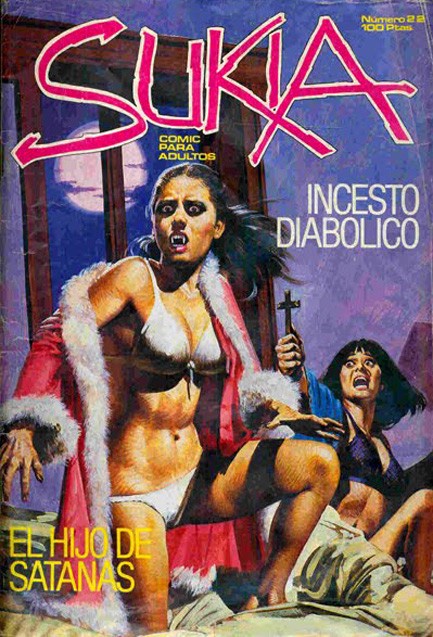

Sweet! Soon AI will allow somebody to animate all these things and the result will be more entertaining than 99% of what Hollywood is putting out these days.This will probably be my last post at least until the weekend is over. It's B-Fest weekend and I start picking people up from the airport tomorrow…