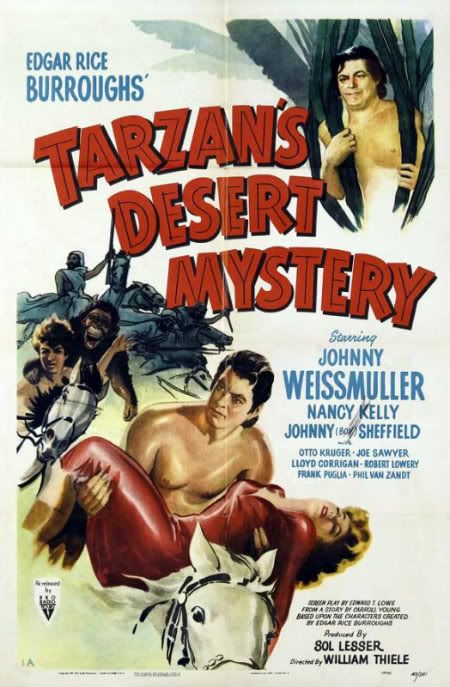

Wait till you see what crazy stuff they didn’t bother to reference in that poster. And in the upper right-hand corner, Tarzan’s supposed to be in mortal danger there. The artist really captured that aspect in Tarzan’s face, don’t you think?

I was never a Tarzan guy. Indeed, I’m never even seen the comparatively opulent MGM movies starring former Olympic champion swimmer Johnny Weissmuller and Margaret (yeesh) Maureen O’Sullivan (!!). I’ll perhaps check those out some day, but they’re further down of the list than, say, the Fred Astaire / Ginger Rogers and Busby Berkley movies I haven’t seen either. However, I heard things about this particular flick that piqued my interest. I think the reasons will become clear as we proceed.

This is part of the Weissmuller series, although by this time the series had petered out at MGM and been revived over at RKO. The films unsurprisingly were ‘B’s there, cheaper and increasingly silly as the skein progressed. This was the second of the RKO’s, and apparently the first where the series truly became juvenile kiddie fare. And indeed, this is a goofy but streamlined entry, offering a lot of lowgrade adventure and kiddie hijinx over a spare 70 minutes.

One reason I never got a good vibe off the MGM / RKO Tarzan’s is that they never let Weissmuller’s version progress much past the “Me Tarzan, you Jane” phase. Edgar Rice Burrough’s Tarzan eventually returned to his native Britain, where he assumed his legacy as Lord Greystoke. That Tarzan was as much a master in our world as he was in the jungle. Weissmuller’s remained a quasi-simpleton, a Rousseauian noble savage. After years spent with Jane he never learned to speak anything other than pidgin English, much less read.

I did rather fancy the last Tarzan movie I saw recently, Tarzan on the Valley of Gold. In that one, former football player Mike Brown assumed the loincloth for the first of his three turns in the role. Made in the ‘60s, Tarzan was recast as a (comparatively) more Burroughs-like suave man of action. He was half Tarzan, half Bond, and it worked pretty well.* All three films are now out on Warner’s DVD-R brand, so I’ll have to check them out. The fact that the Jungle Boy is introduced in one of the latter two doesn’t strike me as promising, but we’ll see.

[*This version of Tarzan operates quite well in the outside world, but in the jungle he was the opposite of Bond. Preparing to track some nefarious villains into the wild, he is promised by the authorities whatever gear and resources he wants. To their amazement, he requests only a piece of leather—to make his loincloth—a length of rope and a good knife. No laser-beam wristwatches for this fellow.]While RKO was able to keep Weissmuller, Johnny Sheffield (the adopted ‘Boy’) and even Cheeta, Maureen O’Sullivan was preggers, and that kept her off the first couple of RKO pictures. Both of these thus offered another female (if not romantic) lead instead. After that, O’Sullivan’s move into the big time clearly removed the increasingly junky Tarzan movies from consideration. And so Jane was finally allowed to return, albeit in the guise of another actress.

While she was still missing in this one, her absence explained by her having left the jungle to become an army nurse to tend soldiers from her native Britain. This was also a way to acknowledge the war without it becoming the focus of the film. Admittedly, the villain (the urbane veteran heavy Otto Kruger) is clearly a Nazi, although the film is oddly reticent about just calling him that.*

[*Instead, he’s revealed to be secretly German, and eventually referred to as a “foreign agent.” Perhaps the studio felt, with some justification, that the actual word ‘Nazi’ was too heavy for a piffle like this to support. Still, the inference is obvious, and with Africa a front in the war—Rommel is name checked at one point—it’s pretty apparent what’s going on here.]In one of the film’s cleverer gambits, however, Jane still manages to drive the plot. Tarzan and Boy—the latter introduced riding with Cheeta atop a baby elephant—receive a (literal) air-mail from her, dropped in a canister from a bypassing plane. This requests that Tarzan journey across the (suspiciously) nearby desert, to another more secret area of jungle. There can be found a cure for jungle fever, which Jane wishes to administer to the sickened troops under her care.

The note explicitly states Tarzan should leave Boy behind. However, the youngster is now a bit of a rascal (not to mention basically a jungle version of Opie Taylor). With the illiterate Tarzan requiring that Boy read the letter to him, the loinclothed lad crosses his fingers behind his back and prevaricates, saying that Jane actually instructs Tarzan to bring him with.

Not to beat this horse to death, but again, it’s hard to swallow a Tarzan who just can’t (or won’t) learn to read—especially since Jane can now only communicate with him through letters—or speak correctly. This is exacerbated by Weissmuller’s obviously encroaching age; the actor was 39 as this was made.

Still a manifestly fit man, it’s yet true that the actor’s beefy frame (more suggestive of an ex-football player than an ex-swimmer) was just starting to soften around the middle. At times, a bit of a double chin is evident. Given his clearly advancing years, Tarzan’s educational deficiencies are starting to suggest Lennie from Of Mice and Men more than the Lord of the Jungle.

“Duh, whatever you say, George. I mean, Boy.”

Still, Tarzan isn’t a chump—he remains Andy Taylor to Boy’s Opie—and quickly figures out that Boy is fibbing. Even so, the lad’s pleading wins his case, and Tarzan allows him to tag along at least until they reach the desert. Needless to say, Boy ends up hanging around for the entire picture.

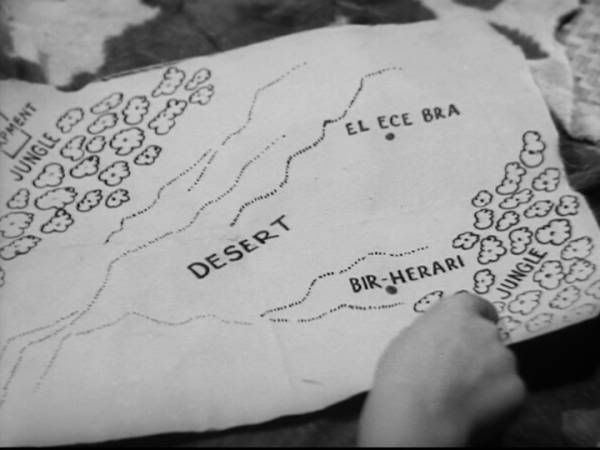

Here we see the hilariously opulent, Swiss Family Robinson-esque tree house the characters live in. Boy and Cheeta return to dig out a rather primitive map of the route Tarzan will take to the medicine. This is again a kid’s idea of a map, reinforcing the fact that the series was now more or less kiddie matinee fodder. The scene is also used to establish Cheeta’s kleptomaniac tendencies, which will drive quite a lot of the action.

“Yes, this should be very helpful.”

So the boys head out to the desert, across which lies the Arabian (and I mean Arabian) city of Bir-Herari. There we meet much of the rest of our principle cast. The lovable but too trusting Sheik Abdul—played by Lloyd Corrigan, who specialized in loveable doofi and was sort of the prototype for actor Hal Smith—his more perceptive son, Prince Selim, and the villain of the piece, Mr. Hendrix. Of shall we say…Herr Heinrich?! Actually, his henchman does say that, before being chastised for doing so. However, it lets the audience know what’s going on.

Meanwhile, Jane substitute Connie Bryce makes the scene. She is an all-American spunky gal with a vaudeville magician’s act. Being overseas to entertain the troops, she has agreed to go on a little undercover mission for Prince Ameer. (I was surprised after the fact to learn that Ameer was played by a young John Dehner. He was rendered unrecognizable by his youth and turban, I guess. Not to mention that he plays the role in a quite jocular fashion, which is the opposite of the rigid, generally sourpuss John Dehner we all remember. Ameer was only his second, uncredited role.)

Yeah, OK, now I sort of see it.

Ameer has been trying to get in touch with Selim about Hendrix, but his previous couriers have mysteriously disappeared. Connie agrees to smuggle in a message for him, hidden inside a bracelet. She knows Ameer and Selim are good eggs, because both matriculated at Yale. Yes, the film is about as patronizing to Arabs and you’d expect it to be.

Meanwhile, Tarzan has allowed Boy and Cheeta to continue with him. Along the way they see the bad guys trying to capture a wild piebald Arabian stallion to curry further favor with the Sheik Abdul. Tarzan, of course, goes all PETA and disarms the main baddie by shooting his revolver from his hand with a bow and arrow. (!!) The freed horse, dubbed Jaynor, decides to join Tarzan for a while.

Then there’s a long supposedly comedic bit where Connie demonstrates her sawed-lady act for her *cough* ‘Arab’ porters. Eventually Tarzan stumbles across this sight, and assumes the worst. He bursts into action, scaring off the porters and leaving Connie, not to mention all her magic act gear, in the lurch. She gives him what-for because she’s a spunky American gal, but relents when he agrees to take her to Bir-Herari.

By the way, I’m always amused when subtitlers don’t get a certain idiom. I think it was around here where Connie complains that Tarzan is “queering my pitch.” This is translated to “clearing my pitch” in the subtitles. Either the subtitlers were too young to have ever heard the phrase “queering a pitch,” or else they assumed people would think ‘queer’ only means homosexual (or actually think that themselves), and so altered the subtitles to avoid any such connotation.

However, Jaynor is still trailer after Tarzan, and Hendrix sends the guards after the jungle man for ‘stealing’ the horse. There’s a bit of an action kerfuffle, but Tarzan ends up in the poky. To Connie’s dismay, as he’s hauled off he assigns her to watch over Boy. This begins the process where the cynical Connie has her heart melted by the loveable scamp, mostly in a scene where he, still in loincloth, recites his nightly prayers. (!!)

Again, the important thing about this film is that it was really aimed at kids, and that Boy was therefore the audience identification figure. Boy has a comical pet ape, and rides around on elephants, and has an impossibly idealized father figure who gets him into crazy adventures but will always in the end keep him safe. They live in a fantasy tree house in the jungle, and all the animals are their friends, except for the mean ones Tarzan occasionally will beat up.

Connie falls into this paradigm. With Jane still in existence, if offscreen, Connie obviously isn’t a surrogate romantic figure for Tarzan. Indeed, Tarzan’s “loneliness” sans Jane seems to have little if any sexual component to it. (Despite the fact that she was played by Margaret O’Sullivan. Rawr.) Instead, Connie is more an older sister or adventurous aunt substitute for Boy; hence her wisecracking tomboyish nature, including her (to a kid) dream job of having a traveling magician act and acting as a spy for the good guys.

Anyway, with most of her gear left in the desert, Connie takes Boy’s suggestion. They basically just set up a clothesline and attract a crowd by having Cheeta do a lengthy tightrope act. And it is amazing even to adult eyes how acrobatic apes are, I have to admit. What an extraordinary center of balance, as we watch Cheeta go from walking the rope to doing somersaults across it.

Because the city is conveniently small—almost like a backlot—Prince Selim notices the act. Spying him in the palace window, Connie draws his further attention by singing “Boola Boola,” the Yale fight song. They arrange to meet that night, and Connie delivers Ameer’s missive, which contains proof that Hendrix is a bad guy. However, Hendrix is on to her, and manages to frame her for murder. The note appears destroyed, but actually Cheeta has stolen the bracelet. It is thus the film’s MacGuffin and ready to be produced at the proper time.

With Connie due to be hanged, Tarzan decides to break out of the jail tower they have him in. There are several easy ways to accomplish this, but for suspense purposes they go with the hardest. First, Tarzan knocks out and secures the guard, but not before the latter has tossed the keys away. The thing is that Cheeta is now in the cell. The bars of the cell are weird and have gaps, too small for Tarzan and possibly Boy but obviously big enough that Cheeta could squeeze through them and grab the keys.

However, that’s not what the script says. So Tarzan sends the ape through the cell’s HIGHLY CONVENIENT open window to collect as many turbans as he can. These they will tie together to make a rope. (Sheets and such would seem more efficient, but what do I know?) So ensues a long comic sequence of Cheeta’s grabbing turbans from the heads of their inevitably befuddled owners.

Eventually, with the hanging just about to commence, Cheeta returns with the assembled headware. Tarzan crafts a line, and he and Boy climb down to freedom. Hilariously, the pre-existing standing backlot tower features a patterned brick façade running all the way down. This basically amounts to a collection of extremely pronounced hand and foot holds. The idea that friggin’ Tarzan the Ape Man couldn’t manage with these (and an open window!), but needed a rope to escape, is highly lame.

“Good thing we had that rope!”

So Tarzan escapes, and action stuff, and he whistles for Jaynor who breaks out of his plywood corral, and they free Connie, and into the desert they go. To allow them to escape Hendrix’ pursuers, the script provides a rather convenient sandstorm. They then find an enqually convenient empty house (complete with a pre-lit fire!) to spend the night, even.

And so they finally make the other stretch of jungle. And it’s here, with roughly ten minutes of movie left, that we get the gonzo elements that drew my attention in the first place. For the place is rife with stock footage slurpasaur ‘dinosaurs.’ These appear via rear projected footage, with Tarzan or Connie or Boy several times pausing in the foreground to stare at the beasts. (Of course, the rear projection thing means any actual interaction with our characters is more or less nonexistent.]

These beasties are clearly borrowed, as any buff would expect, from 1940’s One Million B.C., and inevitably includes bits of the much-borrowed baby finned alligator vs. iguana battle. Man, I wish I had ten bucks for every movie and TV show that used that footage. Still, the interpositioning of the actors and the stock footage is generally pretty expert, except for one instance with Jane and Boy where the stock footage looks kind of washed out.

This is where the liquid that cures jungle fever can be found. This leads to a fascinating field of study, as such liquids are known to be found in places where prehistoric creatures are still extant. Think of the Red Liquid found on Solgell Island, along with the left-over Godzilla eggs and giant mantises and spiders. This also broke jungle fevers, as it was used to save the ailing scientists trapped there. Then there’s the mineral spring that kept Eegah alive all those years. Something start working on this.

Running from the bad guys, Connie and Boy duck into a cave, never a good idea when in prehistoric locales. Sure enough, Boy (you wouldn’t think it would be him, given the whole ‘Jungle Boy’ thing) runs smack into the inevitable giant spider’s web. Cue the big, and in this case rather ungainly, giant spider to menace the two.

Cheeta alerts Tarzan to the pair’s peril, and he runs to aid them. However, he’s so preoccupied that he runs right over one of the film’s rather low-market carnivorous plants. This allows for him to finally, with the end of the film in sight, to unlimber his trademark Jungle Yell. This summons a couple of elephants who free him from the plant with their trunks. The execution leaves a bit to be desired, but man, they sure knew what 10 year-old boys wanted in their movie.

In the end, not to blow things for you, but Connie and Boy are freed, and Hendrix gets et by the big spider. (Who, when we finally get a good look at it, seems to be built upon a modified giant ant head.)

Africa is saved from the Nazi threat, Jane—presumably—gets her fever remedy, and Connie bids a tearful farewell from her newfound pals. The End.

Still, if this is merely the second of the six RKO movies, Jabootu knows what the rest are like. And that doesn’t even count the umpteen subsequent Tarzan movies RKO churned out with Lex Barker and Gordon Scott. Sadly, it’s time for me to return the DVD set I borrowed via Interlibrary loan. Another time, perhaps.

Johnny Weissmuller made four more Tarzan movies for RKO over the next five years. At that point he was 44, and like nearly all beefy muscular men, was starting to go slightly to pot (belly). Obviously Tarzan is a bad character in that situation, what with the loincloth and all. Replaced by Lex Barker, Weissmuller moved over to Columbia and assumed the guise of comic strip character Jungle Jim. This allowed him to pursue the Steven Segal strategy of donning a loose safari jacket to cover his expanding gut.

The cheapie B-movie series ran 16 films (4 more than his Tarzans for MGM and RKO), although for the last three he played “Johnny Weissmuller,” as the producers had lost the licence to the Jungle Jim name. Weissmuller also appeared in 26 episodes of a Jungle Jim TV show in 1955-56. After that he retired from acting, although he played a cameo in the nostalgia wank Won Ton Ton: the Dog Who Saved Hollywood in 1976. Mr. Weissmuller passed away in 1984 at the age of 80.

A similar career arc occurred with Johnny Sheffield, the curly-haired tyke who played Boy. He first played the role at age 8 in Tarzan Finds a Son (1939) and played it eight times, ending in 1947 with Tarzan and the Huntress. Two years later his career resumed when Monogram hired him to star in the Bomba the Jungle Boy pictures. Unsurprisingly, these were even cheaper than the Jungle Jim series. Sheffield assayed the role a dozen times in six years. He retired from the role, and acting, at the age of 24. Mr. Sheffeild passed at the age of 79 in 2010.

Connie was played by Nancy Kelly, a fairly obscure character actress whose main brush with fame occurred when she played the lead adult role opposite moppet Patty McCormack in the original killer kiddie movie The Bad Seed (1956). The part garnered Ms. Kelly a Best Actress nomination, matching an Emmy nomination that same year–1957–for Best Single Performance by an Actress, for an appearance in the anthology series Studio One in Hollywood. Ironically, The Bad Seed represented her final silver screen appearance. She continued to work in TV guest roles through 1977, whereupon she retired. Ms. Kelly passed away in 1995 at the age of 74.

The associate producer of the film was the German emigree Kurt Neumann, a familiar name no doubt to readers of this sight. Mr. Neumann wore many hats over his film career. He is best remembed as a director, having helmed 68 pictures between 1931 and 1959. Most of these were before the ’50s, but it was then he found that certain brand of immortality by directing such genre pictures as Rocketship X-M, She Devils and, a particular favorite of mine, Kronos.

It was in 1958, though, that he really made his mark, helming the original The Fly. It was his biggest movie by far, but sadly he he passed away a week before the film had its general release. Moreover, being a B movie director, three more Neumman movies came out after that one, the final one in 1959.