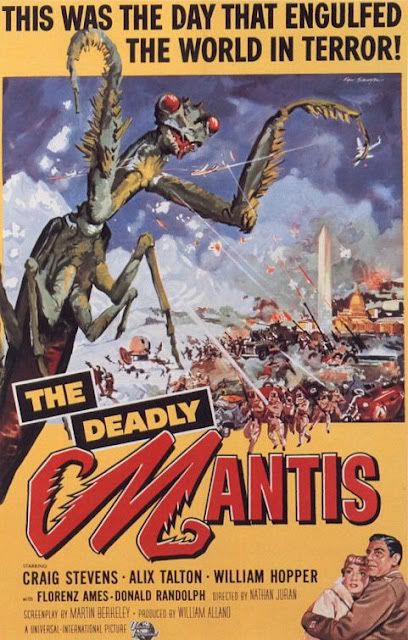

“Universal International unleashes another mammoth insect upon 1950’s America. Peter Gunn is on hand to handle the situation.”

The 1950’s were, in almost every way, the zenith of American pop culture. You’d be hard pressed to find a time in which a better aesthetic and audible quality of entertainment existed. Certainly, monster movies were in their golden age. Them! kicked off a steady stream of enlarged, and enraged, insects that gave the Army a real run for their money.

Universal provided what is considered one of the best of these films, 1955’s Tarantula. Having given the desert a menace that remains one of the most impressive works of special effects ever seen on the screen, the studio turned its attention to the big city for another monsterama. Going for multiple environs, the first half of the picture showed The Deadly Mantis rampaging across the Arctic Circle.

I’ve noticed that one thing that sets Universal films of this period apart from most of their contemporaries is that they would let the audience in on the mystery before the film’s characters, and then we’d follow the characters as they pieced everything together.

In The Monolith Monsters, we see a meteor crash and we discover the fragments have the unusual ability to grow when exposed to water, THEN we’re introduced to our cast and watch them unravel what we already know. In Monster on the Campus, we see a man turn into a monster, but he remains unaware of this for the next half of the movie.

Most science fiction films follow the characters as they observe and piece together the nature of the enemy, and we in the audience join them. In Universal films, however, they seemed to focus on the monster just as much as the hero (supposedly something they picked up from their earlier cycle of more human monsters in the 40’s).

Surely this was designed to keep the monster on screen as much as possible, so as to satisfy the cravings of the audience while also playing out a well-constructed mystery formula. The shocking thing is how well this seemingly counter-productive format works.

Opening with a seemingly unconnected prologue about the early warning systems created to safeguard the free world from potential attack from the Reds, things get off to a good documentary feel as the film details the construction of the DEW line ( the Distant Early Warning radar line, which hugs the arctic circle, was our first line of defense against enemy attack before the proliferation of ICBM’s).

It’s hard for one’s chest not to swell with national pride seeing how swiftly and efficiently this marvel of engineering was put in place. The reality of our setting established, we meet Col. Joe Parkman, played by Craig Stevens! SOMETHING is at large at the top of the world, having already taken down a cargo plane and a radar station.

Of course, one of the first things we saw when the movie started was a glacier rocking and revealing an encased mantis of monstrous proportions. Still, the humans have a mystery on their hands, and they’ll get to the bottom of it. Bodies are vanishing whole from some peculiar disaster sites. In the wreckage of a cargo plane, Parkman finds a huge, sharp object. The sample is flown to Washington, where a cabal of scientists can only determine that the object once belonged to a living thing.

A local paleontologist, Ned Jackson, is called in since his job requires constructing unseen animals from scant evidence. (Jackson is played by William Hopper, who, despite his many other roles, will forever be remembered as Paul Drake on the landmark teleseries Perry Mason.)

Ned quickly figures out the object, from available evidence, appears to come from an abnormally large insect. Ned will need to go the Arctic to investigate the earlier disasters. His photographer sidekick Marge (Alix Talton) manages to tag along in the finest tradition of feisty 50’s female leads who always seemed to have stronger wills than the men around them (seriously, do people who complain about the way women were portrayed in 50’s genre films ever actually WATCH such films?).

It’s sort of unusual for a film like this to have two distinct leads. In most films, one would ultimately be a subsidiary character (and I suppose you could argue that happens here, but not until the final reel, and then not as much as you’d think).

Here, though, Peter Gunn and Paul Drake are both leads, sharing equal importance. Parkman is the romantic lead, though, and he and Marge are almost never apart from the moment they meet at the North Pole.

Before leaving for the DEW line, Ned had narrowed the insect kingdom down to a single candidate: a colossal (and deadly) praying mantis. At night, the command station is attacked by what is indeed a monster of a mantis! The men open fire with rifles and flame throwers, but the creature proves too massive to be harmed by such puny weapons and it quickly escapes.

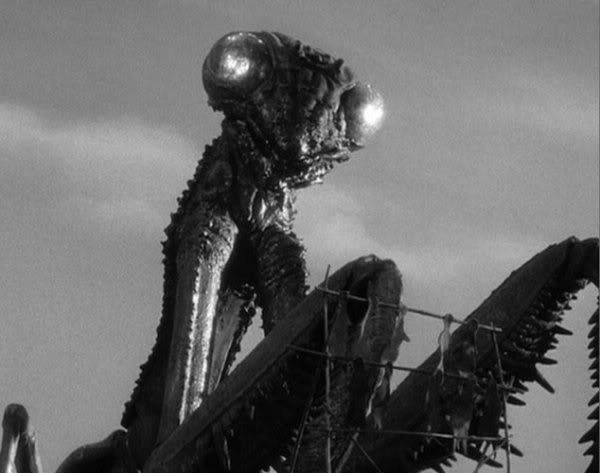

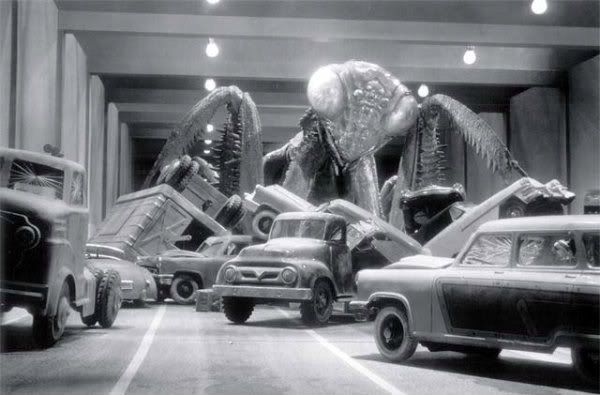

The mantis is really spectacular. The puppet used to realize the creature looks absolutely huge, it must have been about four feet long (and in fact I think I saw a publicity photo that more or less confirms these proportions, or even evidences the prop to be larger)!

It appears to be a marionette in some scenes and controlled by rods in others where the bulk of the body can remain off-screen. (The back legs aren’t as mobile as they could be, and the creature appears to float a bit during the climax.) Happily, the creature looks quite sleek and realistic (in one brief shot a real mantis is substituted and the match is rather good).

For flying scenes, they constructed a rather less impressive (and obviously much smaller) model. Even here, though, the magic of the movies shines bright. In reality, the prop had but one wing that would move. Here we see all four blurred with constant motion when the thing is in flight. Were the body not so static, the effect could have worked quite well.

There’s no dispute, though, the gigantic ‘hero’ prop is a work of art!

The mantis is flying south, seeking the warm and humid climate it desires (I never really understood how a creature that requires warmth and humidity operated so efficiently at the North Pole for so long).

The mantis is a menace and Washington decides to break the news of the creature. Since it can fly below the radar net, the Ground Observer Corps is placed on alert to keep an eye out for the monster (civil defense was once a more active citizen duty, and the film makes much of how important the Ground Observer Corps was to national defense -it could almost be seen as really cool recruitment film).

The Air Force manages to track and engage the beast. Even Col. Parkman takes up a jet. Although it requires ramming the beast with his plane, Parkman manages to wound the creature and it takes refuge in the Lincoln tunnel. There, the final confrontation between man and monster will ensue….

For whatever reason, The Deadly Mantis remains one of Universal’s more obscure releases today. One wonders why, given it’s one of the most giant monster-oriented films the studio ever made. Tarantula has become a much more respected effort, and reference books I’ve seen have never been particularly kind to The Deadly Mantis

.

.

The film is very documentary in feel, and the flow is less like a three-structure play than a police report that’s been committed to film. One gets the idea, in fact, that if Jack Webb produced a monster movie, the results might be something like this.

Another victim of the rapid development of ICBM’s, along with the DEW line and CONELRAD, the Ground Observer Corps was discontinued in 1959.

Rock Baker is a professional comic book artist and writer of Burma Shave verses.