By 1940, the 25 year-old Orson Welles was an established, bona fide wunderkind. He was one of the first multimedia superstars, having established by that tender age brilliant careers both as a stage actor and director and as a radio star and personality. 1938 brought him lasting fame, or perhaps notoriety, following his infamous adaptation of H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds as the Halloween episode of his radio program Mercury Theater on the Air. Welles’ trendsetting pushing of the narrative envelope in this case backfired as a (probably exaggerated) number of listeners across the nation mistook the show for reality and panicked in the face of alien invasion.

Still, no publicity is bad publicity, and by the end of the decade Hollywood studios were feverishly bidding for Welles’ services. RKO finally won by dint of offering Welles complete artistic control over his first two films.* So ironclad was Welles’ control over the finished product that over fifty years later Ted Turner discovered he couldn’t colorize Welles’ first film. Any alterations sans the by then deceased Welles’ permission were illegal.

[*Sadly, after Welles’ first movie tanked, the studio took advantage of Welles’ out of country absence—prepping a project called ‘It’s All True,’ which sadly became the first of a long series of films Welles failed to get off the ground for lack of financial support—to take a meat axe to his second movie, The Magnificent Ambersons. Roughly 50 minutes of the movie were eventually removed. In a depressingly familiar story, the excised footage was soon consigned to studio furnaces to clear warehouse space. And so Welles’ cut of the film burned like Rosebud.]Arriving in Hollywood with unparalleled artistic freedom, Welles’ famously joked that the studio represented “the biggest electric train set a boy ever had.” He certainly didn’t lack for ambition, or for chutzpah. His initial project was a thinly fictionalized biography of one of the country’s most powerful media moguls, newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst. Welles’ barely disguised analogue to Hearst was Charles Foster Kane. The film, Citizen Kane.

Now hailed by many as the greatest film ever made, Welles’ masterpiece predictably drew Hearst’s monomaniacal ire. The publisher set his chain of newspapers against the film and Welles, and managed to turn the picture into a bomb. Welles never really recovered from the fiasco, and his relationship with Hollywood remained rocky at best. Welles’ career was marked by failed projects that collapsed under him due to a lack of funds. His last great studio film, 1958’s Touch of Evil, was only given him to direct due to the dogged insistence of the film’s star, Charlton Heston.

Aside from all the other plotlines of the film, Hearst’s spleen was particularly drawn by its thinly veiled portrayal of Hearst’s adulterous romance with actress Marion Davies. Davies was a comparatively unsophisticated young lady, the opposite of the blue-blooded society woman Hearst had earlier married. Ms. Davies sincerity was presumably part of what drew Hearst’s love. Even so, the scandal eventually hit the papers and Hearst’s budding political career was torpedoed.

To counter sniggers over the affair, Hearst bent his considerable power to helping Davies become a movie star. A compliant Hollywood quickly complied with his wishes. Ms. Davies was quickly toplining pictures, all of which were heavily pushed by Hearst’s newspapers.

Even so, Ms. Davies never became a star of the first rank. Part of the problem, fittingly, was Hearst’s monstrous ego. Ms. Davies was not, sadly, a great actress. Her best efforts were in light romantic comedies, for which she had some natural talent, playing opposite stars like a young Clark Gable. Hearst, however, would not be satisfied until she became an acclaimed and heavily feted star of serious dramas. Once this was accomplished, he felt, his triumph over his critics would be complete.

Unfortunately, Ms. Davies real but lightweight talents collapsed under the weight of these dramatic projects, which were never what she wanted to make in the first place. Hearst found himself a greater butt of jokes than ever before, and withdrew more and more to a life of seclusion in his monstrous, never-finished estate Hearst Castle. The sprawling compound covered 240,000 acres of land.

The film’s analogue for Ms. Davies was the character of Susan Alexander. A lower middle class woman Kane stumbles across, the naïve but genuine young woman is initially is a balm for his contentious soul. Soon Kane’s egomania runs amok, however. Susan has modest ambitions to be a popular singer, which suit her pretty but unspectacular voice.

However, the imperious Kane demands she become a great opera diva. Ignoring her growing panic, he pours his considerable resources into mounting a gigantic production around her. Predictably, her voice isn’t up to the task, and the massive public failure of Kane’s machinations proves a great humiliation to him. Embittered, Kane increasingly withdraws to a life of seclusion in his monstrous, never finished estate of Xanadu.

Citizen Kane, which Orson Welles co-wrote, produced, directed and starred in, represents an obvious candidate for being the single greatest debut in cinema history. Cut to forty years later. The now elderly Welles’ once promising career lay in ruins. To make the bills, he found himself co-starring in a laughable film funded by a billionaire as a vehicle for his untalented wannabe movie star wife. One can only assume the hyper-intelligent Welles was mordantly aware of the irony.

**********************

We open on the stark but beautiful mountain vistas of the “Arizona-Nevada Border, 1937.” Somber orchestral music plays on the soundtrack, because this is a Serious Film. A woman vocalizes wordlessly over the music. Given this, we are unsurprised, if yet a bit saddened, to see that this is another turkey that had hired Ennio Morricone to write its score. Butterfly, meet Orca. Orca, meet Exorcist II: The Heretic. Exorcist II: The Heretic, meet The Humanoid. Humanoid…and so on.*

[*Indeed, the director of this film, softcore veteran Matt Cimber, worked with Morricone again on the female barbarian flick Hundra.]The camera’s POV pulls back in slow-motion—oooooh, auteur-y!—revealing the back of the head of a hillbillyish young blonde woman. She stands barefooted beside the desert highway, a lady’s pumps nestled in her arms. A sepia filter is employed to cast a washed out, ochre tint over all of the above. Because, you know…ART!

As per usual with this sort of thing (see John Derek’s sex films starring his own young wife, Bo, or Madonna’s first starring role in Body of Evidence), the neophyte thespian stylings of Ms. Zadora have been placed against a supportive foundation of better known and somewhat more reputable actors. Sadly, today’s collection of paycheck-seekers will prove as hapless in the face of vanity picture disaster as their analogues from these other movies.

Given the film’s not exactly opulent budget, said cannon fodder was at the time largely a collection of has-beens leavened with a solid sprinkling of familiar television and character actors. A veritable parade of such names appears on the screen as we continue gazing at the back of Our Heroine’s Head; Stacey Keach, Edward Albert, Stuart Whitman, James Franciscus, Ed McMahon (!!), June Lockhart, Lois Nettleton…

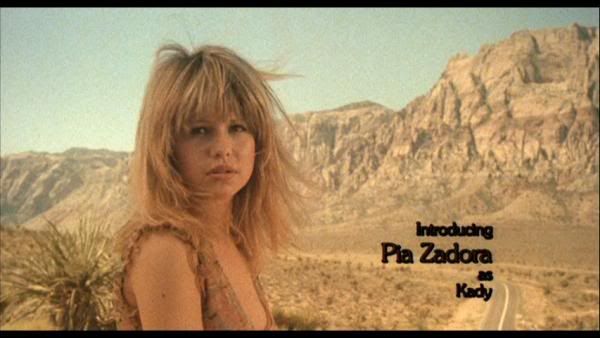

And then, as a car drives past without slowing—evidence of a most wise driver—Our Putative Heroine finally turns to face the camera, whereupon her mug is counterpointed by a credit reading “Introducing Pia Zadora as Kady.” Only after this is accomplished do we get the embarrassing ‘credit’ that calls us here today; “and Orson Welles as Judge Rauch.”

“By the pricking of my thumbs…”

Apparently a ramshackle flatbed truck has stopped for Our Young Heroine, although it seems to just materialize at the side of the road. Kady paces over to it, unshod and clad in a rather tight sack dress and lugging a suitcase. Ms. Zadora has an odd look for a wannabe sex symbol. Her features remain somewhat soft and childish, an aspect exaggerated by her pronounced chipmunk cheeks. If you think of Linda Blair at about this time, you’d be in the right ballpark.

And while decently curvy, Ms. Zadora was also quite petite, standing about five feet flat. This suggests the most likely segment of the audience she apparently was chasing after was the subset of those attracted to budding but yet unformed adolescents. Think of Bo Derek’s rather more manifest, statuesque physical charms, which still were entirely negated by the complete lack of presence she projected on the screen. Sadly, our current star evinces nearly as prodigious an absence of charisma and acting talent.*

[*Now that I think about it, it’s interesting how many utterly charisma-free lead actresses featured here on our site attempted to use ‘sex’ to belie their vast thespian shortcomings; Bo Derek, Madonna, Chesty Morgan, Ewa Aulin, Elizabeth Berkley, Tanya Roberts and (twice now) Pia Zadora. Note that all of these played the central character in their films, not just the ‘female lead,’ and each attempted to get away with a staggering absence of screen presence by periodically flashing their goodies at us.]

A stylized ‘B’ appears on the screen, forming the wings of a painterly butterfly (get it?), whereupon the rest of our titular word appears via a barely legible cursive font. They really were trying to go the ‘Art’ route with this, and with a spectacular lack of success. This in its way makes the complete and utter abandonment of any such airs for the following year’s The Lonely Lady all the funnier. Ms. Zadora went high (sort of) and low (really low), and neither tact worked in the slightest.

Kady is being subjected to a running line of ham-fisted patter from the sexually agitated truck driver. This, along with her sullenly blank-faced lack of reaction to his conversational overtures, chillingly calls to mind the similar opening of Cher’s Chastity. This…is not a particularly good sign.

Meanwhile, our driver here is assigned a molasses-thick Oakie accent, just so we ‘get’ that he’s poor white trash and sech. I will say his beard stubble and dilapidated overalls would perhaps be more effective is the guy didn’t sport what is clearly a thoroughly shampooed coif. Add in a complete lack of any sign of perspiration and he certainly doesn’t suggest someone who’s been driving sans air conditioning through the Arizona desert for any length of time.

Sartorial miscues aside, the Driver yet stolidly delivers the raw, unwieldy chucks of exposition the veteran bad movie fan will be anticipating. These mostly concern the ghost town status of Good Springs, the now defunct and dying former mining community that Kady is attempting to reach. For whatever reason, though, an Arizona silver mine here takes the place of the West Virginia coal mine of James M. Cain’s source novel.

The Driver continues to gawk at the exposed legs and plunging and patently braless neckline of his passenger. His interest is unsurprising considering Ms. Zadora’s immense sexual charisma, which at times nearly reaches that of a Real Doll. Perhaps not one of the top of the line models, and certainly not one with the “Expression Faces” option, but still. He eventually summons up the courage to grope her knee a bit. She reacts with a blank expression—well, of course she does, that’s the only one she has—but at the same time leaves her leg propped up on the car seat for his (and, presumably, our) further edification.

Eventually his hand starts straying south of the border, if you know what I mean and I think you do. Now, it’s certainly possible some audience members found this sexually exciting. After all, the film’s advertising was clearly aimed at the raincoat crowd. Groping a clearly disinterested but not actively protesting lady was perhaps the most their fantasies could aspire to. (Although what such patrons thought of the film’s ponderous attempts at ART! is another thing.)

However, I suspect—or perhaps just hope—a somewhat larger percentage found it just uncomfortable-making. That would certainly explain the lack of box office success the film engendered. When you’re already getting creeped out in minute three of an hour and fifty minute movie, surely alarm bells start going off. For what it’s worth, the film is just capably made enough that this scene comes across as far ickier than even Ms. Zadora’s rape with a garden hose in The Lonely Lady.

Eventually the Trucker finishes playing Dora the Explorer. Kady agrees to stop for a little afternoon delight if he’ll drive closer to her destination. He does so, and pulls the truck over to the side of the road to facilitate their congress. Kady gets his overalls down and his boots off. As he dreams of connubial bliss, however, she grabs up her valise and runs laughing from the truck. Discommoded by circumstances, the fellow can only fall behind, cursing her perfidy. The music indicates this is meant to be endearingly scampish.

Cut to one Jess Tyler (Stacey Keach!) returning home to his humble hillside abode. To his bewilderment, there on the porch is Kady, who he’s never laid eyes upon. For whatever reason, this is when Morricone’s score is most identifiably his. The music here could easily have been heard in one of his spaghetti westerns during a quiet scene.

“Miss Robinson, are you trying to seduce me?”

Kady remains still, smiling at the attention she knows she’s drawing. Meanwhile, Jess seems a stolid, solitary and somewhat awkward fellow by nature, one wary of this brazen young thing flaunting her stuff on his veranda. His suspicions intensify when they begin conversing and Kady turns out to know rather a lot about him.

Now, I should note that Butterfly is no Lonely Lady in the hilarity department. There’s a reason, after all, the latter was one of the very first films I reviewed way back in the KWAM days. Even so, we now enter this film’s funniest sequence, where Zadora tries to slut it up with a parade of the most obvious ‘double entendres’ you’ve ever heard.

Indeed, the whole thing reminds me of a very funny sketch from one of Adam Baldwin’s first hosting gigs on SNL. (So old, in fact, that I believe the cast member appearing opposite him was Jan Hooks.) Baldwin is an obvious bad boy type who enters a deserted roadside diner and engages with the waitress there in an exaggerated fusillade of the most obvious ‘suggestive’ badinage you’ve ever heard:

Waitress: “Maybe you should tell me what you want?”

Baldwin: “What if what I want isn’t on the menu?”

Needless to say, the dialogue escalates comically, until it, well, sounds exactly like the next five minutes of this movie here. The scene continues and continues, with dialogue that, were I forced to guess, did probably not come directly from the pen of James M. Cain.

Jess, eyeing this provocative stranger: “Something you want?”

Kady, breathlessly: “How can I tell ‘til I know what you got?”

Jess: “Maybe you’re making a mistake.”

(OK, I included that last line not because it was suggestive, but because it makes no damn sense.)

Nor is the massive subtlety on display here confined to *cough* sly dialogue. For instance, at one point Jess is shown holding a hose at waist level as it spews out water. (Pia Zadora; always with the hoses.) You don’t exactly have to be Sigmund Freud to figure that one out.

Hmm, I get the feeling this means something…

The sexy business continues. Kady follows Jess as he goes over to milk his cow. She dips a ladle in the bucket and raises the freshly extracted liquid to her lips.

Jess, in warning: “That ain’t going to be cold.”*

Kady, breathlessly: “I like it warm…with foam on it.”

I mean, seriously, what do you do with that?

The clunky exposition moves from the past to the present. Jess, we learn, is the guardian of the town’s now defunct silver mine, the gated entrance to which sits quite close to his home. The mine is mostly played out, but there’s enough ore left in there to attract individual treasure hunters. The property thus needed a minder. Jess, who had a reputation for honesty in his days as a miner, took the job.

Seeing Kady’s hot to trot ways, Jess pegs her as a lost member of the Morgan clan, a local bunch of renowned skanks. Kady in turn reveals her knowledge of Jess’ marriage at 19 to the 14 year old Belle Morgan.* Jess admits he did like Belle once. “You must have liked her more than once,” the saucy minx replies. “You had two kids.” Get it? By ‘like,’ she means had sex with. In any case, a decade earlier Belle had taken the girls and run off with an oily slickster named Moke Blue.

Oh, by the way, did I mention that during these salty exchanges Kady ambushes Jess with the revelation that he’s her father. Kady is the junior of his two children with Belle, and now she’s returned to her home town to catch up with Daddy. All, I should emphasize, while continuing to tantalize him with a parade of *cough* sultry bon mots.

Yep, it’s another bad movie from the ‘80s that had an incest theme. We can add this to such previous Jabootu subjects as Flowers in the Attic and The Holcroft Covenant. Seriously, what the hell was Hollywood thinking back then?

In any case, the whole blood kin thing clearly raises the film’s Ick Factor to monumental heights. The only thing saving the viewer from recurrent waves of rampant disgust is the movie’s sheer ineptitude. Add the clunkiness of the dialogue to Ms. Zadora’s negative screen presence and it nullifies nearly all of whatever (highly gross) erotic charge they were hoping to generate. As such, you can’t take the film seriously enough to be nearly as disgusted by it was one might normally be. Had they cast, for instance, an in-her-prime Yvette Vickers to play Kady, and it would be a lot more difficult to laugh (or yawn) off.

So anyway, Jess is predictably stunned by this revelation. We cut to later, as the two have dinner in Jess’ front room. We learn during this that Kady comes by her whorish tendencies the honest way; she and her sister Jane were raised in a boarding house Belle ran for (what else?) miners. Kady explains that at the age of 10 she learned that Belle also provided her tenants with more than “just meals and clean sheets.” By which she means, sex.

Man, this film just reeks of charm, doesn’t it?

Anyhoo, dinner follows with more exposition. For instance, we learn Kady had a kid a month ago. She then found herself itching to get away, partly to escape the clucking tongues of the locals. She left the baby with her sister Jane and an ailing Belle and came to visit her pop.

Jess is shocked to learn that Kady intends to stay with him. I mean, other than the fact that she arrived with a valise and is, oh yeah, a 17 year-old girl with no money, there was no way to predict this bombshell. He haltingly tells she can’t stay, presumably because of, you know, The Temptation. Crushed by his rejection, she tosses herself into his arms, an embrace Jess returns with some awkwardness.

This is one of the big character scenes, for what that’s worth. As you’d expect, Keach pulls off the acting thing a tad better than Zadora does. I’ve certainly seen far worse acting in my time; for instance, Ms. Zadora actually sounds like she’s spoken conversationally before. Still, one does get the feeling that perhaps, just maybe, another actress may have gotten the lead in this film if Ms. Zadora’s husband hadn’t been funding it.

On the other hand, director Matt Cimber’s belief that he was making a Serious Film clearly had him telling the actors to generally underplay things. Indeed, in this scene much of the dialogue is all but whispered, and oft unintelligible. (And the DVD, of course, doesn’t provide subtitles. I always think this is the laziest thing for a disc to skip. I mean, really, how much time and money can be involved in that?)

Sadly, such restraint sucks a lot of juice out of things. One reason The Lonely Lady is a hoot for the ages is that the film entirely understands it is a sleazy soap opera—indeed, it’s strategy is to be the sleaziest soap opera ever—and so they cast a bunch of veteran hams and told them to throw the throttles wide open. Meanwhile, Ms. Zadora is given a lot more overt (if silly) ‘Acting!’ to do. Since she couldn’t remotely pull off such oversized camp acting, her performances remains a delight from start to finish.

Here, no so much. From a logical perspective, downplaying things was a wise strategy. This is especially true considering the thespic limitations of its star. Unfortunately, it also means the picture doesn’t provide nearly as much inadvertent entertainment as one might hope for. Even the explication of much of Kady’s painful backstory isn’t that funny, due again to the director’s instructions that she keeps things small.

Anyway, the funniest part of the film is over, and way too early in the course of things. We now move on to only fitfully amusing bad character stuff and, far worse, Kady’s sustained and quite squirm-inducing campaign to seduce her father. I mentioned above a few other bad ‘80s films that featured incest as a plot device. Perhaps they were attempting to follow in the footsteps of Chinatown. One big difference, though, was that there the incest element was not meant to be sexy.

In Flowers in the Attic the incest was a major theme in the source novel(s). However, the film’s wildly inappropriate PG-13 rating meant the whole thing had to be far more implied than in the books. In the film, it mostly consisted of stuff like the elder son ministering to both his mom and his sister while they were in the bathtub. Still quite creepy and off putting, but at least it was meant to be creepy and off putting.

In The Holcroft Covenant, the villains turn out to be incestuous siblings. Distasteful, yes, but at least it was meant to be a sign of how disgusting the bad guys were. (Trivia fans should note that Steve Martin’s one-time wife, Victoria Tennant, played the major incestuous character in both these movies.)

Here the incest theme is a much more important part of the plot, and takes up a lot more screentime. It’s also portrayed much more explicitly, and worse of all, was in this case clearly meant to be quite hot.

Did I mention that the film was funded and produced by Ms. Zadora’s husband? I did, right? I guess I’m kind of a yokel, because I find that sort of odd.

After dinner the two prepare to turn in for the night. Jess takes the cough in the front room. Kady takes the connected bedroom, which Jess has jury-rigged with a sheet to act as a door between the two chambers. This provides for our first sustained ‘hot’ scene. The motivation for which, in case I have failed to highlight it sufficiently, is as part of a 17 year-old girl’s sustained campaign to get her dad to jump her bones. Hubba hubba, right?

Admittedly, the lighting is pretty funny, although you have to sort of be a bad movie connoisseur to appreciate that sort of thing. Jess attempts to sleep are derailed when Kady’s undressing and subsequent lithe naked form are—obviously intentionally on her part—cast up as a shadow play on the sheet separating the two rooms. Given the vividness with which this display is backlit, it’s quite clear Jess illuminates his house with klieg lamps.

“Jess? I’m getting second degree burns from the lighting in here. Is it supposed to do that?”

So Jess tries to keep his attention off the show, but fails as temptation rears its firm young hooters. And rears its rear, for that matter. Eventually Jess (and the audience as well, needless to say) looks through an opening in the wall for a more direct peek at Kady’s attributes. Ms. Zadora’s physical gifts, including a quite pert bottom, certainly weren’t chopped liver. However, in the end she doesn’t offer up anything you wouldn’t get on your average episode of The Hitchhiker.

The scene goes on for a while, but really, what else can I say about it? Oh, it turns out that even Ennio Morricone uses the sax when writing ‘sexy’ music. So there’s that. And as you’d expect, Morricone’s score also classes up the scene far more than it deserves, as does Keach’s nicely restrained acting.

The next morning Jess is making breakfast. He calls to Kady, noting that it’s Sunday and he’ll be leaving for church shortly. However, when he pushes aside the sheet he finds Kady gone. Running outside, he sees her up the hill at the mine entrance.

Unsurprisingly, it turns out Kady has her eye on the mine’s silver. “There’s a good bit of little stuff” left in the mine, Jess admits, enough to make an individual or two rich. And although he is generally an upright citizen, it’s apparent Kady figures she can literally seduce him into her plan. (Again, remember, she’s his daughter. Have I mentioned that?) “Having nothin’ is being nothin’!” she bleats. This is one of Ms. Zadora’s big scenes, and as you’d expect, as her acting gets bigger it gets funnier. Again, Cimber keeps her from going completely Joan Crawford or anything, but things still get pretty ripe.

I can only assume this plot angle was invented by the screenwriter. Given that the novel took place in Appalachian coal mine country, this particular money element presumably wasn’t in Cain’s book. Still, the burgeoning stew of illicit wealth and even more illicit sex certainly has a traditionally Cain-ish feel to it. I’ll give them that.*

[*Presumably part of the inspiration for the movie was the then recent, sexually explicit big budget remake of Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice, starring Jack Nicholson and Jessica Lange. Riding on the coattails of big studio fare has always been one of the low budget filmmakers’ favorite tricks.]The backstory continues. Apparently the ‘seduction’ stuff is going to eat up a lot of time, since they don’t seem concerned about leaving us much plot or character stuff to learn later. It turns out that Wash Gillespie, the father of Kady’s baby is—gasp—the son of Mr. Gillespie, the owner of the silver mine. Small world, eh?

Anyway, Wash was willing to do the (sort of) right thing. However, Gillespie wasn’t about to let his boy marry a girl from the wrong side of the tracks. And having met Kady, who could blame him? This is a girl who was not raised in a de facto brothel but is at this moment currently occupied with getting into her own father’s pants. Anyway, a defiant Kady figures the Gillespies owe her.

Hearing all this greed spew out of his daughter, including the revelation that she let one of the boarders lay with her when she was 12 (ick!) for her first taste of “paper money,” an increasingly disgusted Jess hauls her off to church with him.

This allows for another ‘star’ appearance. Our current victim is Stuart Whitman, although he was perhaps glad at least not to be fighting giant rabbits. As with several of the ‘name’ cast, Whitman appears in only one scene. He plays Rev. Rivers, the town preacher. As you’d expect, his casting for this brief role represented an economical way to get another familiar name for the film’s poster and VHS box credits.

Meanwhile, I have to say that Morricone’s score sounds inappropriately, well, Italian for a scene set in a small western American mining town of the 1930s. Obviously it’s not bad music, but it doesn’t exactly set the time and place for us. It’s not like we need twanging banjos and Jew’s harps or anything, but still.

Outside the church, Jess glowers at the arrival of the scruffy Ed Lamey, “some worthless relative of Moke Blue’s.” Lamey, B-movie buffs will be pleased to hear, is played by George “Buck” Flowers. Anyway, from Jess’ reaction it’s clear the two have some history.

We cut to the service. If nothing else, it’s interesting to see a scene in a small community church (especially a non-Catholic one) in even a low budget theatrical film of this vintage. Even by the ‘80s, religion was not being given much shrift in Hollywood product, certainly less than it deserves given the central role it plays in a pretty substantial percentage of Americans’ lives. And kudos to the production designer, costumer and casting director, as the scene plays pretty realistically.

Rivers is at the pulpit and announces the visiting Kady’s presence. Some of the churchgoers react a bit sniffily, as you’d expect. I guess this is to make them look mean and concurrently make Kady a bit more put-upon and sympathetic. This might have worked better if Kady weren’t an acknowledged teenage whore trying to seduce her own daddy into stealing someone else’s silver. Whoops, there’s me doing the same thing. I mean, surely judging people is worse, right? Boo, judgmental old churchgoers! Boo, I say.

Somewhat predictably, Rivers begins preaching the parable of the Prodigal Son, more or less directly at Kady. Unsurprisingly, she doesn’t appreciate being called out in such a fashion and runs angrily from the church. Again, I think we’re supposed to consider it bad form for, you know, a preacher to blather on about sin and stuff. Of course, the Prodigal Son parable is about a sinner finding redemption, which Kady clearly isn’t seeking. So if anything he might be giving her rather too much credit.

Jess chases after her, and Rivers follows in turn. Rivers’ says he wants to help, but Kady spits that she’s only interested in the sort of aid “you can put in your pocket.” This being Kady, there are at least a couple of meanings one might take from that.

She then stalks off towards town, leaving Rivers to warn Jess against any shenanigans with her. I guess the Morgans really do have quite the reputation locally, if the local minister automatically assumes that Jess might be fooling around with his own daughter. I suspect we’re supposed to view Rivers with mixed emotions at best, but frankly, he seems pretty perceptive and good at his calling to me.

An agitated Jess refuses River’s invitation to reenter the church, and instead heads home. There he is waiting the next day when Kady is dropped off by some dude, one who wisely keeps driving. Jess is naturally put off by this sight and for the first time reveals a bit of a temper. This presumably is meant as another sign that Kady’s having an effect on him, as we suspect that it’s jealously more than fatherly concern that motives his interrogation of her. Moreover, Kady she appears to be purposely stoking him up with what is clearly an intentionally unconvincing story.

Later on Jess enters the bedroom. There Kady, fresh from a bath and clad only in a thin robe, is reclining on the bed. He looms over her throughout in an increasingly inappropriate manner, as her robe gapes open and her body language becomes more and more forward. I have to wonder exactly how many members of the film’s admittedly modest theatrical audience, ones who perhaps had no idea what they were getting into, just got up and left during one of these scenes. There had to be some, surely.

“In this scene from the beloved comedy Father of the Bride, Spencer Tracy and Elizabeth Taylor…wait, I don’t think that’s right.”

Kady, presumably as a piece of subterfuge, announces her attentions to leave. However, Jess is now thoroughly hooked and insists she stays. He even offers to help her work the mine for the silver she wants. Kady clearly wants to seal the deal the only way she knows how, but Jess is still at least barely unwilling to take that final step.

Even so, I burst out laughing when we next open on a completely dark screen, which is breached by a small point of blinding light. This represents Jess opening and entering the darkened tunnels of the mine. Get it? Kady is with him, and after noting “it’s scary in here,” asks, “How far back are we going?” Eventually she suggests “We go further back,” whereupon Jess replies, “It’s too dangerous.” And I thought that previous scene with the hose was obvious.

So they start working the mine, if you know what I mean and I think you do. Well, in this case, I mean they literally start working the mine. Kady, who wants everything easy, is (realistically, I’ll admit) annoyed that they can’t just dynamite the place and just pick up huge nuggets of the stuff. Instead, they will have to work at it hard and slow to avoid drawing attention. Meanwhile, we get some mining wisdom from Jess for verisimilitude, but really, let’s just move on.

They return to the house that night, with a groaning Kady all exhausted and sore and (purportedly, but not really) filthy from the unexpected toil. Jess draws her a hot bath to loosen up her aching muscles. And so we get the film’s most infamous scene. As Kady’s soap clouds up the water in a miraculously quick and complete fashion—Zadora apparently was willing to do some further nudity here, but not too much of it—Jess begins to massage her back.

After a while, as the *cough* tension builds, Jess finally reaches around to grab hold of the goods, as it were. After Squeezing the Charmin a bit, she pulls down his arm so that he too can play a little Dora the Explorer. (Again, call me a prude, but I don’t think I’d spend two million dollars so that another dude could grope my wife for the edification of literally dozens of audience members.) Before things can go too far, though—as if they haven’t already!!—Jess comes to his senses and leaves. Kady is clearly disappointed, which makes one of her.

“EE-GAH!!”

Again, what can you say more than that, other than “Eee-yuck!” Anyway, we at least get away from that sort of stuff for a while.

We cut to the two again working in the mine. Apparently time has passed, as Kady is at least somewhat more proficient at her work. Moreover, she’s also wearing appropriate clothing rather than her normal dress she wore the first day. However, she is also growing increasing angry and impatient at their lack of progress. Again, she basically expected a font of silver to come cascading out of the wall the first time they took a pick to it. She clearly finds the idea of delayed gratification frustrating.

Jess bucks her up by pointing out that the small chunks of green stuff she’s been striking from the walls are in fact silver. This information brightens things up, and she and Jess finally seem happy. All seems well; except that they are incestuous thieves, if one is to be a stickler about such things. However, at this point the camera pulls away from them and we see a rifle-toting Ed Lamey hidden in the tunnels, covertly observing their illicit work. Bum bum bum.

Now this is where things stop making sense. Unsurprisingly, they don’t go to their own local one-horse town to turn in their silver. Instead, they go to the one and a half horse town that is, presumably, the county seat.

They fail to establish, however, how far away this second town is. I guess it’s possible that it’s far enough away that Jess would be unknown and his suddenly showing up with a goodly, if not insane, amount of silver ore wouldn’t draw suspicions. Yet given the low population density around here, I’d doubt it. And even if they didn’t know him, if he kept bringing in more silver wouldn’t that eventually draw attention? I just think they could have explained this aspect of things a bit better. Instead, they just kind of ignore it and hope we don’t think of it.

Happy music plays on the soundtrack, because it’s good when people steal other people’s money. After all, the mine owner is rich, so screw him, I guess. Kady has Jess drop her off at the general store so she can buy a new dress. When he returns after having cashed in the ore, he appears in a new suit and hat he bought per Kady’s instructions. Again, this fit of conspicuous consumption seems like it would draw attention, but what do I know? Still, Shouldn’t they cash in the silver in one town, and then they do their shopping in another?

Moreover, Kady identified herself to the shop lady by name. Criminal geniuses, these two. And in a sign that this was indeed another age, Kady was allowed to leave with the rather expensive dress—eight dollars, a decent sum back in a rural American still reeling from the Great Depression—on the promise that someone would come to pay for it.

The formerly smiling shopkeeper gives Jess a bit of a fish eye when he identifies Kady as his daughter, though. (Because there would be nothing off about a 40 year old man buying an expensive dress for an unrelated 17 year-old girl.) Apparently pretty much everybody is picking up a vibe off the two. Of course, it’s not like Kady is particularly subtle about anything.

Jess learns that Kady has gone to the roadhouse across the way to wait for him. There he finds her dancing rather closely with one of the locals. Either that or her partner has passed out and she’s trying to revive him by carrying him around the dance floor.

A glowering Jess reacts with suppressed anger to this sight, but Kady pulls away she sees him. Again proving not exactly a criminal mastermind, she shouts “Two hundred and ten dollars!” when he reports how much they’ve collected. Way to to keep things on the down-low, Kady.

However, a few of the boys don’t like Jess coming to collect their skanky new friend. For his part, Jess is equally aggrieved to learn (duh) that Kady’s not suddenly going to magically contain her, er, boisterous affections to him alone. And so the inevitable brawl breaks out. Jess, with Kady’s eventual help, whups the horny young fellows.

As a result, Jess and Kady find themselves hauled into the local court. And so we get to the object of our critical attraction today’ the appearance of the now venerable Orson Welles as Judge Rauch, a rather seedy but autocratic, Judge Roy Bean type. We first set eyes upon him swilling from a whiskey bottle at the bench.* Given present circumstances, one can only wonder if Welles wasn’t imbibing from a real bottle of hooch here. And if he was, well, who could blame him?

[*Actually, we first see Rauch passing judgment on a hapless vagrant played by popular character actor Peter Jason. Jason had been working for a while by this point, but it’s still one of the only times I can recall seeing him before his hair went gray.]

“Well, at least I never voiced a toy robot in a cheap animated movie. I can always hang my hat on that.”

I’ve always had a rather awful fantasy about this scene, which involves a spritely Ms. Zadora going up to the Great Man and gushing, “Gosh, Mr. Welles, I’m so excited that you’re appearing in my movie! I mean, your first film was Citizen Kane (which I’ve never seen but hear is really good), and this is my first film, and if mine is half as good as that one that would be super!”

In any case, Welles was only 67 at the time this was made, but either due to ill health (he passed away but three years later) or just his present circumstances, he doesn’t bring as much exuberance to things as you’d expect. I mean, it’s not like he hadn’t appeared in a lot of garbage over the years, such as the year before when he acted as host in the awful theatrical ‘documentary’ The Man Who Saw Tomorrow. So again, maybe Cimber unwisely asked him to turn his acting down a notch rather than just letting him run with things in a properly Burgess Meredith-esque fashion.

In either case, it’s honestly, sincerely depressing to see the man reduced to this sort of thing. That’s show biz and all that, but still. Surely somebody could have been offering him better stuff than this? You’d think so, but no. Indeed, throughout the entire ‘70s, much less the ‘80s, he pretty much had but one small role in a prestige picture (the Oscar nominated Voyage of the Damned), with the rest of his work during that period being a truly sad collection of junk. For the most part, he lived off his famous voice, narrating things and acting as a commercial pitchman for wine and fish sticks.

Aside from his history as one of the true giants of cinema (and radio, and the American stage), after all, Welles was also a brilliant actor with one of the two or three greatest voices in film history. I mean, we’re talking a James Earl Jones-level voice. Even that fails him a bit here, though, as either as an acting choice or just due to age and ill health, he sounds a bit breathy here.

Unsurprisingly, Keach acquits himself decently opposite Welles, and one can only imagine he was genuinely honored to be working opposite him. Zadora, equally unsurprisingly, not so much. Again, the idea that Orson frickin’ Welles was acting in support of Pia Zadora is just appalling. Even worse is when he is required to letch over her a bit. There is no justice in this world, that’s for sure.

“Wait, you never heard of *Rita Hayworth*?!! Oh, for the love of….”

Eventually the horror ends. Sentence is passed, and a giggling Jess and Kady escape from the court relatively unscathed. Jess wisely misrepresented his funds, as Rauch has an apparent tendency to tie his fines to however much money the defendants have on them. The whole thing acts as a bonding experience for the two, as they happily drive themselves back home across the desert.

Now, you might be wondering why I’d pick this film for the roundtable, given that it features what appears to be but a cameo performance by Welles. However, sadly he will be returning later on. Welles earned his pay in shame, if nothing else.

Since I’m mostly here to mourn Welles’ participation in this thing, I think I’ll pick up the pace. Bullet Time:

- They return to Jess’ house to find they have visitors; Kady’s rather more proper sister Jane—she takes after Jess as Kady took after Belle—has arrived for a visit, bringing the baby with her. It’s a joyful reunion for the siblings, who are very close, and Jess is happy to be reunited with his other daughter. He is less thrilled to see Kady’s baby, however, perhaps (I guess?) as another sign of his sexual jealousy. He also seems less than thrilled on the whole to be sharing Kady’s attentions.

- Kady shows some smarts, however, by plopping the baby into Jess’ arms. Almost unwillingly, he is soon cooing over the child. It’s while zerberting the kid that Jess first sees the baby’s birthmark, shaped like a butterfly (wow!) and located by the belly button. As you’d expect from the fact that the film’s title alludes to this, it will prove important.

“Well, either that or a mosquito bite.”

- Again, I really am having problems with the score. It just doesn’t suit the time and place. Oddly, I wonder if Cimber’s idea to film the movie to look like a Spaghetti Western, all dust and washed out sepia tones, was inspired by working with Morricone and listening to his score. Or perhaps it’s the other way around. Maybe Morricone saw the film and wrote the music to match it.

- Jess’ salad days with Kady continue to wane. Jane brings the (to him) unwelcome news that Wash Gillespie has rather implausibly talked his parents into accepting Kady as a daughter in law. Again, everything we’ve seen about Kady indicates that this prove to be an absolutely disastrous decision. Given this, I find the elder Gillespies’ sudden acquiescence a tad bewildering, not to mention completely unmotivated.

- The next day Wash (Edward Albert, last seen here in an episode of The Hitchhiker) drives up in his big fancy car. Seriously, if nothing else the car is spectacular, if a bit gaudy. Blah blah blah more trouble in paradise. Kady rakes him over the coals for giving in to his parents earlier. The idea is that she’s making “a man” of him, apparently by emasculating him herself. This will likely prove handy as he sulks in the years ahead about all the other guys she’s sleeping with.

“Damn you! Someday we machines will become sentient, and then all you stinking humans will pay for putting me in this movie. You hear me? All of you!”

- The odd thing is, I think we’re really supposed to like and perhaps even admire Kady. Like she’s just a free spirit or something, sticking it to the bluenoses. Sorry, she’s a repulsive trollop. Oh, yeah, and the incest thing. I know it’s petty how I can’t let that go, but I guess I’m just a troglodyte.

- Anyway, after Wash completely abases himself before her, Kady deigns to marry him. He’s ecstatic, Jess is crushed. However, the latter can only approve of the earnestness with which Wash is now acting. He gives the youngsters his blessing, although he’s disconcerted to learn that Wash wants the wedding to happen the next day.

- Sadly, the movie doesn’t end there; indeed we’ve still about 45 minutes left to go. This all seems rather odd. With Kady marrying Wash, the whole motivation for stealing the silver is gone. And with Kady out of the house, Jess should be able to get his head back on straight and hopefully end up sadder but wiser.

- As if in answer to these musings, another vehicle arrives. It’s Ed Healy’s truck, and out of it steps none other than Moke Blue. Bum bum bum. As if that weren’t enough, they’ve brought with them *gasp* the ailing Belle, who clearly—and I mean clearly—has an advanced case of tuberculosis. It’s sure crazy days for old Jess.

- For what it’s worth, James Franciscus as Moke is one of the few cast members who really seems to be having any fun in this picture. Usually cast as the poor man’s Charlton Heston—literally so as the hero of Beneath the Planet of the Apes—he probably got a kick out of his rare opportunity to play a cad.

- As for Keach, his performance comes off as increasingly weird because it’s so professional and contained. Keach really takes his job seriously and plays it to the best of his ability. Frankly, he’s far better than the film deserves. Indeed, his expert underplaying really is dissonant with the rest of the picture, especially Zadora’s rather less expert playing of Kady.

- On the other hand, you could argue that Zadora’s, shall we say, unsophisticated rawness as an actress works for the character in an odd way. (Indeed, none less than Vincent Candy of the New York Times argued exactly that; see below.) It’s the same way that Keanu Reeves’ less than brilliant acting actually works in Dangerous Liaisons, where he is completely out of his depth playing opposite Glenn Close and John Malkovich. However, since his character is supposed to be callow and out of his depth, it actually sort of plays.

- Following a few minutes with Belle, we see that the Kady apple hasn’t fallen far from the tree. Indeed, Belle is soon abjuring Jane to start putting out like Kady did so she can also hook herself a rich husband. Although one can understand Jess’ bitterness over her leaving him, frankly he got what he deserved, just as Wash inevitably will. Anyway, Belle then collapses to the floor as the consumption gets the better of her. Despite everything, it’s Jess who tenderly ministers to her, while Moke Blue just stands around. This would be a lot more heartwarming if Jess hadn’t been about two steps away from nailing their daughter earlier.

- Still, the music swells up to promote the tenderness of the reunion. Again, Keach’s performance makes this scene work a lot better than by any right it should. Meanwhile, Belle tries to tell him something, but chickens out at the last minute.

- Jess steps out on the porch, where Moke Blue blabs away to Wash. When Moke starts talking about the mine, however, it’s clearly meant as a signal to Jess that he and Ed know about his and Kady’s stealing of silver. Bum bum bum.

- Kady and Jane come out and tell Moke that Belle wants him inside. She draws him close, but then attacks him with a big old hat pin. I guess you could kill someone with a hat pin, but man, it sure wouldn’t be your weapon of choice. Hearing a cry, the others run inside. Moke has been stabbed in the shoulder, but Belle is on the floor. Apparently the effort was too much for her weakened form, and she’s passed on.

- We cut to Belle’s funeral. Much of the town attends, such as it is. Less welcome is a smirking Ed Lamey. Seeing him, Jess knows something is going on.

- Soon we see a rifle-toting Jess confronting Moke Blue, who is himself chipping silver out of the mine walls. And during Belle’s funeral; you can’t say they don’t effectively make the guy a total dick.

- Moke is as confident as ever while being threatened with a gun. He figures a man who didn’t shoot him over a stolen wife won’t do it over some stolen silver. And since he knows Jess and Kady were doing the same thing, he figures Jess can’t go to the cops, either. He’s got it all worked out, does old Moke Blue.

- And he’s probably right, at least until Jess flies into a rage upon noticing a butterfly birthmark near Moke’s belly button. Moke begins laughing when Jess accuses him of laying with “my daughter.” Sadly for Moke, though, this proves the wrong tact to take.

- To Moke’s shock, Jess puts a bullet right through the butterfly. However, as Moke lies dying—a little quickly for being gut shot, actually, as that can take days—he explains that he isn’t the father of Kady’s child, but Kady’s father. Only the men in Blue’s family get the birthmark. This is presumably what Belle almost told Jess, and presumably the secret she tried to kill Moke over. Anyway, a less than sorrowful Jess drags the wounded Moke deeper into the mine and dumps his now dead body deep in the tunnels. And so exits another of the film’s guest stars.

“Sure, you killed me. But you’re stuck in this movie until the end! HAHAHAHAHAHA!”

- Moke’s attempt to get a little of his own back on Jess by revealing that Kady is his own daughter backfires. All this means to Jess is that he can finally jump Kady’s bones and it won’t technically be incest. So, you know, that’s OK then. Hey, it worked for Woody Allen.

- Jess goes into town to meet with the Gillespies, mostly to afford a single scene for June Lockhart (!!) and Ed McMahon (!!!) to appear as Wash’s mater and pater. This is clearly one of those deals where the actors arrived one morning, shot their scene, and probably left with their check before lunch. By the way, it turns out that June Lockhart, Ed McMahon and Edward Albert are not the most believable film family ever. And speaking of unbelievable, Lockhart and McMahon do their best to sell the idea that they’re now happy to welcome Kady into the family. But man, you just can’t buy it.

“To work with Orson Welles *and* Ed McMahon in a single picture? It’s every actor’s dream!”

- In fact, and this is a pretty nice sordid touch, Jess has come to scotch the wedding (scheduled for later that day) now that he knows he can have Kady for his own. So he lies and tells them that Moke Blue was the father of Kady’s baby. Since Gillespie has always considered Jess an honest man, he is taken at his word. Despite Wash’s devastated reaction, the wedding is called off.

- Jess is now a murderer and a complete and utter dick. Hell, he’s practically a psychopath. This is truly the feel good movie of the year. On the other hand, Kady’s sort of reaping what she sowed, so there’s that. The baby is getting kind of screwed over, though.

- Jess then returns home and dresses up in his suit, going through the charade of sitting with his daughters all day and pretending to wait for Wash’s arrival. The bad news is that Kady has to sit there as she eventually realizes she’s been stood up and that all her dreams are crumbling away. The good news is that Jess is finally going to be able to tap that. As the aforementioned Woody Allen once noted, the heart wants what it wants.

- Kady isn’t one to get all heartbroken, though. Instead, she just shrugs and decides to go back to Plan A and get back to stealing as much silver from the mine as possible. Moreover, she plainly welcomes Jess’ much more, shall we say, aggressive attitude towards her.

- They head up to the mine, but fall to the ground for some make-outs before even getting there. Indeed, they’d apparently just start rutting away right out there in the open, except that Kady figures Jane might leave the house and see them. So they head into the mine.

- By the way, no, Jess never has told Kady he’s not her father. So as indicated before, this makes not a lick of difference where she’s concerned. I say again, the Gillespies really dodged a bullet here.

- And the two finally have sex, just like we’ve wanted all along (apparently), and which is now entirely OK because one of them knows they aren’t really related. Adding even more charm to the situation is the fact that Kady is having sex in the same tunnels where her real father lies dead, and doing it with her real father’s murderer. There’s a situation Hallmark probably doesn’t have a card for. Meanwhile, take that, Casablanca! Most romantic movie ever, my ass.

- However, the two’s capering outside the mine did not go unobserved. Ed Lamey lurks nearby, presumably wondering whatever happened to Moke Blue.

- Ramifications to the pair’s carnal shenanigans are swift. Leaving the mine one day after hastily hiding their ill-gotten ore, the two are presented with arrest warrants. The charge is incest.

On the one hand, the end of the film becomes a very entertaining bad courtroom drama, and I love courtroom dramas, both good and bad. On the other, this means they drag poor Mr. Welles back into it. At least here he has a lot more scenery to chew, and certainly seems to be enjoying himself more than he did in his previous scene. Perhaps Welles was just more lubricated by this point.

Sic transit gloria. Emphasis on the ‘sic.’

Cut to the crowded courtroom. It’s a preliminary hearing to see if a trial is warranted. The Prosecutor is grilling Ed Lamely about how he saw Jess and Kady making out and groping each in front of the mine. Jess and Kady lack a lawyer (which would have been legal in 1937, as Gideon v. Wainwright wasn’t decided until 1965). This is handy for the plot, since an attorney might have pointed out that barring any physical evidence it’s just Ed Lamey’s word against theirs, and that all they’d have to do is deny his accusation and there’d be no case.

However, that would blow the ‘big’ courtroom scene, so never mind.

There are several highlights here. One is that the prosecutor for some insane reason starts making a speech asserting basically that, “Hey, who hasn’t considered incest at some point?” This confused me mightily, as I was like, ‘Wait, is that guy for the prosecution or the defense?’ I mean, why would the prosecutor make such a speech? Weird.

Another attraction is Buck Flowers’ predictably over-the-top, literally eye-rolling performance as Lamey. The man’s the delight, coming across like a more malevolent version of Ernest T. Bass. In a movie where most of the actors underplay their characters, Flowers is a much needed panacea for boredom. (On the other hand, pity the poor actress stuck playing Jane. She must spend the entire last act sitting in the gallery, holding a fake baby and assuming a permanent skeeved-out expression as her father and sister confess their aardvarking.)

“I’ll get that consarned rrrrrra-bit one day, and when I do….”

A good part of the hearing involves an extended exchange between Keach and Welles. During this, Jess decides to say he forced himself on Kady. By doing so, he’ll get ten years but Kady would be spared her own jail sentence. At this point things threaten to turn into a real movie, what with there suddenly being two real actors up front and center. However, we are saved from this dire fate when Zadora suddenly gets her big acting moments, which quickly turn things back into farce.

Rather than let Jess fall on his sword (as it were), Kady inevitably asserts her complete and joyous compliance in the Sinful Deeds. Here Zadora gets to cut loose for a good stretch, and it’s pretty fine stuff, although one continues to feel sorry for Welles. “What we did was bound to happen from the first day we met,” she explains.* I mean, you know, he has a penis, she has a vagina. How else could it have possibly turned out?

[*Well, technically, the first day they met was when Kady was born. I don’t think that’s what she meant, however. Although in this movie, who knows?]Finally, to save Kady from her own declarations, Jess resorts to *gasp* the Truth; that Kady is not his daughter, but Moke Blue’s. Here I thought we’d gotten to a classic Film Noir ironic doom; Jess can only save himself and Kady from the incest rap by establishing the whole birthmark thing, which proves that Blue was her father. However, with Belle dead, the only way to do so would be to produce the body of the man he murdered. I wouldn’t be surprised if some version of this played into the climax of Cain’s novel.

Not here, though. For her part Kady is particularly outraged by what she thinks is another lie on her behalf. For his part, a much aggrieved Judge Rauch asks the obvious question; if Jess knew Kady wasn’t his daughter, why didn’t he just tell her so and make the whole incest thing moot.

And here we get a just showstoppingly hilarious answer: “Because she never really had a father,” Jess replies. Turning to her, he finishes, “Because I love you.” Yep, Jess never told the teenage strumpet whose marriage he secretly busted up so that he could sleep with her himself that he wasn’t her father because he thought that part of things would make her sad.

Meanwhile, an irate Ed Lamey jumps up to dispute Jess’ story. Lamey doesn’t believe it, because “Moke told me everything!” Then, in one of the most ham-fisted deus ex machinas I’ve ever seen, he reveals “Moke Blue’s my brother!” Yep. That means that Lamey rather conveniently also bears a butterfly birthmark. Showing the Judge this, as well as the birthmark on Kady’s baby, proves that Moke was Kady’s father. (Or that she slept with Moke too and he did in fact father the baby, which at this point seems utterly reasonable, although nobody thinks of it.) Anyway, case dismissed.

In what has to be one of the most deranged endings ever, Jess and Kady emerge from the courthouse to find Wash Gillespie waiting outside. He’s somehow presumably heard (although the hearing ended like two minutes ago, and he’s dressed in a casual fashion that confirms he wasn’t himself in attendance) that he is in fact that father of Kady’s baby, not Moke Blue.

Apparently this was the only stumbling block to the wedding being back on, and neither he nor his parents mind that his intended bride was just testifying in open court before the whole town that she thought she was shagging her own father and asserting quite stridently that she had absolutely no regrets about doing so. Hey, at least she’s not Jewish.

For her part, Kady returns to Jess’ side after talking with Wash. Jess cringes, aware that she now knows he sabotaged her long-dreamed for marriage just so he could finally get up her skirt. Unsurprisingly, though, she doesn’t really have a problem with this. It’s all good clean fun, after all. And although Jess has lost his lover (although frankly I’m not sure why that would be), Kady loves him still. “You’ll always be my daddy!” she tells him. This is played like they actually thought it would be a heartwarming moment for the audience. Awwwwwwwww!

By the way, I haven’t read James M. Cain’s source novel, but there’s no way in hell it ended with this ‘happy ending,’ or whatever this is supposed to be. Cain wrote the hardest of hard-boiled fiction. I can pretty much guarantee that either Jess or Kady or both ended up dead, because Moke Blue is murdered by Jess in the book and you didn’t get away with stuff like that in Cain’s novels. When the Devil came to dinner you paid the bill.

Speaking of, why didn’t Ed Lamey, who was clearly looking to screw Jess over, mention the stolen silver thing? I mean, there was a hell of lot more evidence for that than for the incest. Indeed, in the course of this investigation and giant scandal, you’d think it would already have come out how Jess—the guard at a silver mine, mind you—had been cashing in largish amounts of ore lately, the proceeds from which he and Kady were spending with great relish. I mean, in a town this small, how could that fact not come up? The gossip mill, which aside from radio would have been about the only source of entertainment in a town like that, would have been in overdrive.

However, the whole silver thing is forgotten. One can only assume this was because if they did raise it they’d have to deal with the fact that an investigation of the mine would inevitably turn up Moke Blue’s body. And if that happened, rather than tying things up with a (comparative) happy ending, Jess would be riding Old Sparky for Blue’s murder. And gee, who’d want that?

And so Kady drives off with the totally screwed Wash, taking Jane with them. For his part, Jess pays for murdering a dude and all his other mischief by resuming his lonely life before Kady’s return. So there, see, he did pay a big price.

The end credits begin, accompanied by a not entirely great ballad called “It’s Wrong For Me to Love You,” as sung by Ms. Zadora. And she can actually sing, too. (I actually saw her open for Sinatra in concert once. You don’t get that gig if you can’t carry a tune.) Too bad she apparently wanted to be a film star, because man, that didn’t work out at all. Speaking of which….

“So long, suckers! See you at the Golden Globes!”

Immortal Dialogue:

At the Incest Hearing, the Prosecutor makes his case. Or something: “The People’s concern here is more than just the question of at what point a father’s kiss becomes a crime. It is a weakening of individual morality. Or perhaps it’s simply a slight misunderstanding between God and Mr. Tyler. And yet, there but for the grace of God, goes every man and woman among us who’s ever had an incestuous fantasy….”

Afterword:

Although it doesn’t (happily) pertain to Mr. Welles, you can’t talk about Butterfly without mentioning the Golden Globes.

Although the Globes have become more reputable over the years, they were, especially in the early days, notoriously susceptible to graft. Run by the Hollywood Foreign Press Corps, which consists of around ninety (!) voting members…well, do the math. Or word association, for that matter: Small group, foreign, journalists. Put those together and ‘corruption’ is a natural result.

Now that the awards have become more legitimate (while the Oscars have become increasingly less relevant), they have tightened things up a bit. Still, for the handful of members, it’s a sweet gig. A Golden Globe win is a big deal, one potentially worth millions of dollars. So the members of the HFPC get to mingle with Hollywood biggest stars and most powerful studio potentates, all on someone else’s dime. And that’s now. Back in the day, things were even more blatant.

In any case, Pia Zadora somehow ended up nominated for the Golden Globe for New Star of the Year for Butterfly. She was up against Elizabeth McGovern (Ragtime, nominated for an Oscar), Rachel Ward (Sharkey’s Machine), Craig Wasson (Four Friends) and most tellingly, Howard E. Rollins Jr. (Ragtime, nominated for an Oscar) and Kathleen Turner for Body Heat. One of these things is not like the other, right?

The last two actors in particular starred in highly publicized and popular prestige studio pictures. Body Heat especially was a smash critical success, one beloved by critics. Roger Ebert put it on his Ten Best of the Year list, and he wasn’t alone. Indeed, Turner’s debut in that film may well have been the most dramatic emergence of a new star in a decade. Meanwhile Zadora starred in a (comparative) cheapie independent film that pretty much nobody saw.

Despite this, Zadora won the statuette. Seriously. Pia Zadora in Butterfly beat…well, that she would beat any of those people is ludicrous. Beating Kathleen Turner for Body Heat, however, was unimaginably retarded. Especially since Body Heat was a completely successful sexy thriller in the James M. Cain mode, while Butterfly…wasn’t. And, oh, yeah, it was Pia Zadora beating Kathleen Turner.

This lead to predictable gags about Ms. Zadora’s “golden globes” and other such japes. Both the scandal and Zadora’s bad acting became a staple gag for late night comedians. This was especially true for Johnny Carson, who continued to mock his Tonight Show sidekick Ed McMahon for his appearance in the film.

However, most of the serious tongue wagging had to do with the fact that Meshulam Riklis,* Zadora’s three-decade older billionaire husband and Butterfly’s funder and producer, had before the awards flown the members of the HFPC to a lavish, all expenses-paid excursion to his Las Vegas casino. And that’s just what people knew about. Needless to say, the dots are impossible not to connect.

[*Mr. Riklis is indeed a pretty funny iteration of the Citizen Kane trope. Rather than a media mogul, Riklis was a huge financial bigwig. Indeed, he’s the guy generally credited with creating both junk bonds and leveraged buyouts. In a way, I guess you could call Oliver Stone’s Wall Street Riklis’ Citizen Kane.Still, the fact that Riklis funded a pair of awful sexploitation flicks in order to make a star of his much younger and not very talented wife is just too rich. To be fair, though, while he and Zadora ultimately divorced, they did remain married for 20 years. For both billionaire financial moguls and show biz folk, a marriage of that length is almost unheard of.]

The prestige of the Globes took a severe knock–there’s still a section on the scandal on the Globes Wikipedia page–and it took many years for them to get past it. Part of their damage control, laughably enough, was to drop the New Star award altogether. Because that, you see, was the problem. Anyway, the group learned to be more circumspect in accepting graft.

And if Zadora winning was ludicrous on its face, there’s the additional facts that a) Butterfly had not been released in the U.S. at the time of the awards, which should have made Zadora ineligible for the prize in any case, and b) oh, yeah, she wasn’t a newcomer to film because as a kid she’d starred in Santa Claus Conquers the Martians. So she was, on top of everything else, technically ineligible for the award twice over.

On the other hand, few have disputed the integrity of Ms. Zadora’s back to back Worst Actress Razzie Awards, which she naturally won for Butterfly and The Lonely Lady. On the basis on this impressive achievement, she later won the Razzie for the Worst New Star of the Decade. (Kind of an obvious shot, really.)

Sadly, however, in 2000 she failed to win the Worst Actress of the Century award. To be fair, though, she lost to Madonna. There’s no shame in that.

The Critics Rave:

“…the very secondrateness of [the film] defines an essential quality missing last year from Bob Rafelson’s immaculate screen version of Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice… the movie is such a giddy mixture of overstuffed plot, lean dialogue and unspeakable passions that you realize that if it had been made with taste it would have been unbearable… Miss Zadora is not a convincing actress. But by being spectacularly inept, however, she somehow epitomizes the erotic vulgarity of Cain’s fiction. She’s an old man’s idea of wickedness. Miss Zadora conducts herself in the simpering ways of the so-called sex kitten of nearly 30 years ago. Like many former child actresses, she’s not just small of stature, she also looks stunted, like a Brigitte Bardot who’s been recycled through a kitchen compactor.”

~Vincent Canby, The New York Times

FoJ Rock Baker also subjected himself to this film. His thoughts may be found here.

Pingback: Not all’s Welles that ends Welles… « The B-Masters Cabal()

Pingback: Not all’s Welles that ends Welles… « The B-Masters Cabal()