Bela Lugosi played Dracula thousands of times on stage, but only twice onscreen. The first time was in 1931’s Dracula, the film that kicked off Universal Studio’s famous series of classic horror movies. After that, though, Universal handed the role off to John Carradine (pretty good) and Lon Chaney Jr. (woefully miscast). Lugosi was 66 years-old by the time he was allowed to assay the role on film again, in 1948’s Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein.

Bela Lugosi played Dracula thousands of times on stage, but only twice onscreen. The first time was in 1931’s Dracula, the film that kicked off Universal Studio’s famous series of classic horror movies. After that, though, Universal handed the role off to John Carradine (pretty good) and Lon Chaney Jr. (woefully miscast). Lugosi was 66 years-old by the time he was allowed to assay the role on film again, in 1948’s Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein.

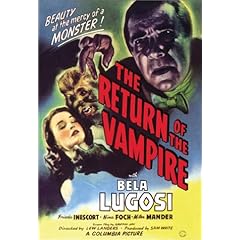

During the interim, however, Lugosi played Dracula-like vampires and pseudo-vampires in many other films. Return of the Vampire, made by rival studio Columbia, was the film that most heavily resembled Universal’s (and Lugosi’s) take on Dracula, to the point where a lawsuit must have at least been contemplated.

As with Universal’s The Mummy’s Tomb, Return of the Vampire was one of the few movies from this period to play with the idea that these monsters were immortal. The film opens in the London of 1918, and for the first fifteen minutes events very closely follow the events of Universal’s Dracula. Only minor details have been changed to keep Universal’s lawyers off their, er, necks.

A girl (basically Mina Harker) is in the sanitarium of Dr. Jane Ainsley (a female Dr. Seward), suffering from a mysterious case of anemia. Ainsley calls in an older colleague, Dr. Saunders (the Van Helsing analogue), who declares the situation the work of a vampire. This is Armand Telsa, a Romanian investigator of the occult who centuries earlier had become one of the undead. He’s in London now, and using mind-controlled underling Andreas (i.e., his Renfield) to serve him.

When Tesla’s original victim dies, he turns his attention to Saunder’s eight-year old granddaughter, Nicki. (Nicki is also a playmate of Ainsley’s slightly older son, John.) Saunders convinces Ainsley of Tesla’s existence, and they track down Tesla’s coffin and drive a metal spike through his heart. They are almost stopped by Andreas, but Tesla’s destruction frees him.

As you can see, only minor changes have been made from the events in Dracula. Dr. Ainsley is a woman instead of a man. The vampire is dispatched with a metal spike rather than a wooden stake. Most noticeably, Andreas is, for no real reason, a talking, non-feral werewolf. (!!) Only with Tesla’s destruction does he become a normal man again.

Twenty-three years later, the Blitz hits London, and Tesla’s body is disinterred. Two woefully unfunny comic relief cockneys remove the spike before reburying him (thinking it a piece of bomb shrapnel), with obvious results. Tesla stalks the land once more, and tragically, the weak-willed Andreas is again brought under his spell. Meanwhile, the vampire seeks vengeance against Jane, and also to claim the now adult Vicki as his undead bride.

The film moves along steadily as is necessitated by its 70-minute running time, albiet often via a series of plot-advancing, if credulity-straining, coincidences. Even so, the action is often torpidly paced, although not as much as the London scenes in the 1931 Dracula. What it comes down to is that a majority of the film’s characters are pretty dull. When they are holding the screen, viewer interest tends to flag.

The film has its share of outright goofiness, too, especially the pointlessness of Andreas being a werewolf who never really acts like a werewolf. (Of course, the real reason he’s a lycanthrope is so that his furry visage could be featured on the film’s poster art.) Even when he’s jumped by a pair of cops, Werewolf Andreas escapes by pasting one of them with a haymaker (!). Even funnier is that in nearly every scene featuring Werewolf Andreas, he is carrying a neatly-tied bundle of Tesla’s laundry. (!!!) So much for a vampire’s clothes being supernaturally clean.

Despite all that, though, the sub-plot featuring the tragically ensnared Andreas sub-plot is quite affecting, and easily the best part of the movie. Much of the credit for this must go to the fine, understated performance by actor Matt Willis.

The adult Nicki, meanwhile, is played by Nina Foch (who played a werewolf—an actual four-legged one—in the same year’s Cry of the Werewolf, another film I’d like to see hit DVD). Foch is OK, being about as good as one can expect given the slightness of the writing, but she is at least highly beautiful. (The woman playing Jane Ainsley must have thought so too. She has a disconcerting habit of putting her hand upon Foch’s, er, chest.)

The rest of the cast is pretty lame, though. The comic relief is generally painful, and several of the characters, including Jane, Saunders and a Scotland Yard Inspector, are played with several helpings of British reserve too many. Given the nature of what we’re dealing with here, their placid demeanors become increasingly comical.

The film belongs to Lugosi, naturally, although he doesn’t have a huge amount of screentime. Still, his presence here, playing Dracula in all but name, definitely earns the movie a place in horror film history.

Several plot devices here, meanwhile, were to be recycled in later Dracula pictures. The Count killing a man and then assuming his identify occurred also in The Return of Dracula (1958) and the hideously bad but hilarious Billy the Kid Meets Dracula (1966). Dracula seeking revenge by striking at his target(s) through their children was the plot of Hammer’s Taste the Blood of Dracula. Meanwhile, Dracula reestablishing control of a former Renfieldian servant to advance his agenda happens again in Dracula, Prince of Darkness.

Tech credits are decent, with heavy use of the fog machine to help obscure some obvious, if suitably gothic, sets. The film was directed by Lew Landers, a journeyman director who helmed over 150 films (!) in his career. Notably, he had earlier directed Lugosi (and Karloff) in Universal’s The Raven (1935). Landers brings an occasional touch of flair to the proceedings, but mostly is merely efficient.

Return of the Vampire is available on a bare boned DVD. The presentation is solid, if not sparkling, although it’s good to have the film available after decades of relative obscurity.