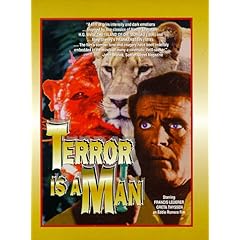

Producer / director Eddie (credited here as “Edgar”) Romero was born in the Philippines in 1924, and is fondly remembered by horror and B-movie buffs for a series of sleazy horror films he produced and often co-directed in the ’60s and ’70s. Terror Is a Man was his first such effort. As a neophyte, it’s perhaps natural that Romero cribbed from one of the most famous horror tales set on a remote, verdant island; H. G. Wells’ oft-adapted novel The Island of Dr. Moreau.

Producer / director Eddie (credited here as “Edgar”) Romero was born in the Philippines in 1924, and is fondly remembered by horror and B-movie buffs for a series of sleazy horror films he produced and often co-directed in the ’60s and ’70s. Terror Is a Man was his first such effort. As a neophyte, it’s perhaps natural that Romero cribbed from one of the most famous horror tales set on a remote, verdant island; H. G. Wells’ oft-adapted novel The Island of Dr. Moreau.

Shot in typically atmospheric black and white, and in an era that wasn’t conducive for the gore and tits he was later known for, it’s yet obvious that Romero’s exploitation instincts were already firmly in place. The film thus opens with a William Castle-esque text card. This warns that one scene is so shocking that it will be signaled with a bell—shades of the more famous ‘Horror Horn’ from Chamber of Horrors—and helpfully suggests that “the squeamish and faint-hearted close their eyes” at this juncture.

As usual with the period, the film doesn’t waste much time. The opening shot (under a bad superimposed ‘fog’ effect’) shows a dingy floating towards an island shore. Two men pause from combing the beach, and discover an unconscious man in the boat. They carry him off, but pause first as an ominous animal howl sounds elsewhere on the island.

From there we meet our limited cast. The marooned sailor is one William Fitzgerald, the man who saved him is Dr. Charles Girard. Girald has a statuesque blonde wife, Frances; a violence-prone henchman, Walter; and a few servants, sexy island girl Selene and her young brother Tiago.

Fitzgerald recovers, and of course gradually uncovers the Awful Truth: Girard is conducting surgical and chemical experiments in accelerated evolution. His subject is a panther that years of work have gradually transformed into a quasi-man. However, the beast, unsurprisingly terrified and bewildered by what is happening to it (and, in the best tradition of deranged henchmen, regularly tormented by Walter), periodically escapes and uses its still be-clawed hands to wreak murderous havoc.*

[*The make-up is minimal, and the film is smart enough to swath the creature in mummy-like bandages in order to disguise this. Even so, one evident marker of the beast’s origin, along with the clawed hands and cat-like whiskers pushing out from its bandaged face, are a pair of pointy little cat ears. Had Gerard made a cat-woman instead of a cat-man, and kept not only the ears but the tail, he presumably could have gotten himself a lot more funding, from Japan if nowhere else.]

Terror is a Man (the title refers more to Girard, presumably, than his piteous if murderous creation) is a quite good example of how solid execution is more important than a novel concept or characters. The dialogue is consistently efficient and interesting, which is especially helpful in that the movie can be a bit talky in-between the monster bits.

Meanwhile, a cast of talented actors (ah, the days in which the casts of horror movies were made up of, you know, adults), along with a script that ably limns the characters, avoids plaguing us with what could easily have been a tiresome parade of the usual stereotypes; the mad scientist, his neglected, frightened but sympathetic (to the ‘monster’) wife, the stolid hero, etc.

One element that clearly marks this as one of Romero’s films is the air of open sensuality. Westerners, especially sailors, have for centuries been enraptured by island populations of handsome people who were quite casual about sex. This sexuality marks Romero’s oeuvre, with naturally greater explicitness as the years went on. Even here, however, Selene is portrayed as Walter’s mistress with a frankness that is a little surprising, given the production date.

Moreover, Frances’ wishes to get off the island are motivated not only her fear, but by the lack of attentions she’s been getting from her work-obsessed husband. Fitzgerald, naturally, is instantly smitten with her, and (again for the time) is surprisingly quick to make a clearly sexual move on her. “I’m not lonely,” she replies, rebuking his overtures. “I’m frightened.”

However, we know that this is not entirely true, given an earlier scene where she—unknowingly watched by the then at-large monster—writhes alone in her bed in erotic frustration. Later, though, after spurning his advances, she watches Selene go off with Walter one night, whereupon she finally breaks down and seeks out Fitzgerald for a little release.

The end of the film is especially interesting. (SPOILERS!)

The monster, badly wounded, is aided by Tiago (which is kind of weird, given events, although it plays into the idea of the creature as an innocent victim.) The kid apparently—I’m not sure why this isn’t directly shown, perhaps they shot it and the film didn’t come out—ships the seemingly dying beast out in the small boat the similarly incapacitated Fitzgerald arrived in. It’s a nicely bookend to the beginning of the film.

However, assuming Romero was already thinking in terms of sequels, this climax also calls to mind his later Beast of Blood, the second of two films centered on the creature who became known as the Chlorophyll Monster. The Monster is apparently destroyed at the end of his first outing, but the sequel begins with the creature springing from a lifeboat and gruesomely slaughtering the crew of a freighter. It certainly seems possible that Romero was already thinking of a sequence like that with the end of this movie, and merely filed it away until he had a chance to use it.

(SPOILERS OVER.)

As noted, things are definitely helped by a good cast, who in underplaying their parts manage to ground them with a nice sense of reality. The budget for the film was obviously small, but the interior sets are pretty good (if obviously still sets), and the authentic jungle / island exteriors lend the film an expansiveness not often found in films of this nature.

I watched the film on the old Image DVD. Much of it is quite sharp (as only black and white is on DVD), although some of the exterior night scenes are noticeably washed out. Moreover, the sound is pretty poor. These faults probably are inherent to the film itself, although it would have been nice if Image had provided subtitles, given the weakness of the soundtrack. Wellspring later put out another DVD version, utilizing the same print and featuring supposedly better sound. That disc is cheaper, as well, and features a couple of extras, so anyone seeking to pick up the film should probably go with that version.

Fitzgerald is portrayed with quiet conviction by genre veteran Richard Dix, who has a sort of William Holden thing going. He invests his character with a natural intelligence and curiosity, so that his obstinate investigation of Girard’s work seems motivated more by his nature than the necessities of the plot.

Dix is best remembered as the star of When Worlds Collide, and played Lamont Cranston, the Shadow, in The Invisible Avenger. He also appeared in a lot of genre TV shows spanning several decades, including Lights Out (several episodes), Tales of Tomorrow, the original The Outer Limits, Project UFO and Automan. He played Adm. Fitzgerald—no relation, presumably—in “The Mark of Gideon” episode of the original Star Trek, and appeared in another episode, “The Alternative Factor”, as well.

Girard, meanwhile, is equally well assayed by the suave Austrian actor Francis Lederer. Lederer had, presumably unknown to himself, achieved a low-grade immortality the year before this by playing the Count in 1958’s Return of Dracula, a similarly efficient low-budget film that was one of the first to bring Stoker’s character to then modern America.

Lederer apparently actively resented being in movie, thinking it beneath him as a classical actor, although again it’s the one that he’ll always be remembered for. (And, indeed, he would play the Count again in The Night Gallery segment “The Devil is Not Mocked.”) Thus is the passion of the horror movie community, who never forget a credit. Happily, Return of Dracula itself is scheduled to hit DVD in December.

Lederer’s work here is equally good. Girard is clearly nuts, but it’s a quiet nuts and all the more credible for it. We all like a guy who just goes for it and chews up the scenery, but Lederer’s performance here matches the understated tone of the rest of the movie, and helps to sell it in a surprisingly credible manner.

Director Gerardo de Leon was a mentor to Eddie Romero, and directed and co-directed (with Romero) many of Romero’s horror films, including Blood Drinkers (1966), The Mad Doctor of Blood Island (1968), Brides of Blood (1968) and Curse of the Vampires (1971). Mr. de Leon passed away in 1981.

Eddie Romero found his commercial niche, as noted, in a series of increasingly lurid horror films. His most memorable creation by far was the green-blooded and grotesque “Chlorophyll Monster,” a beast that gained notoriety from drive-in fans for his tendency to dispatch his victims in what was for the time an extremely gory fashion.

In the course of making his films, Romero worked with several work-seeking American actors (Patrick Wayne, Sig Haig, Angelique Pettyjohn), much as genre filmmakers in Japan and Europe did. One-time teen idol John Ashley was his regular star, and the two made eight pictures together. Ashley apparently prepared for such assignments with roles in earlier works such as Frankenstein’s Daughter and Larry Buchanan’s The Eye Creatures.

It’s too bad, really (although many others will obviously disagree), that Romero’s later films went so enthusiastically in the blood ‘n’ babes direction. Terror is a Man proves that he could easily have emulated Val Lewton instead of Al Adamson.