While I think my reputation for lambasting hippie movies is a tad exaggerated. I’ve done, what, four now? This, the two Billy Jacks and Chastity? Maybe The Harrad Experiment, I guess. Anyway, this is indeed another. If you don’t dig hippie-bashing, please move on for your own sake. Meanwhile, the Jabootu Pointing Finger of Blame is oriented accusingly in the direction of Jabootu contributor Pip Vandergeld, who

foisted this horror on merequested I review this film. How could I refuse? The woman endured Dirty Love for us.

There’s a weirdly persistent tradition of American film studios hiring foreign directors to make essentially anti-American movies. I’d like to think it’s because American directors are less likely to want to make pictures like that, but I rather doubt it. More likely, the idea is that as outsiders these foreigners see America more clearly than the natives do, although the actual cinema results suggest this is not the case. In any case, especially in the 1960s and ’70s, for every satire and critique of America and its essential institutions (M*A*S*H) shot by an American, it seemed like several others were made by foreign-born directors.

The Platonic ideal for this sort of thing was English director Stanley Kubrick. [OOPS!! Kubrick was actually American, a fact several readers in the message section properly chastised me on. He moved to Britain at the age of 34 and stayed there the rest of his days. This obviously is a major flaw in my argument, although it’s notable that Kubrick commenced his films directly critiquing America immediately after the move, filming Lolita and Dr. Strangelove during that period. He directed his first officially British-set film, A Clockwork Orange, in 1971. Kubrick continued to direct films ostensibly set in America, but actually shot them in England: The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, and his last film, Eyes Wide Shut.]

He examined and dissected America, with varying degrees of success, in a series of films ranging from Lolita to Full Metal Jacket. His masterwork, however, and still the high water mark for political satire, was Dr. Strangelove. This is probably because, in direct contravention of most similar films of that (or any) era, it fails to demonize either America’s political structure or even its military. The problem, the film tells us, is not so much the American system, as the fact that there are crazy people in every system.

Indeed, Kubrick pays our military an essential respect. Dr. Strangelove portrays our forces as dangerous to a possibly apocalyptic degree exactly because they are so professional and competent. The film continues to speak to modern audiences because it posits that the real problem is that humans will always find a way to screw things up, no matter how elaborate the precautions set in place. This dire but strangely affectionate view of Man’s Folly is why Strangelove remains important and relatable over forty-plus years later, while it’s more smugly hectoring and straight-laced counterpart, Fail Safe, seems so staid and didactic.

However, Strangelove remains a rare bird, especially for its time. With ‘counterculture’ films all the rage back in the day, Hollywood produced an array of triumphantly awful films about What Was Wrong with America. And, as noted, many, perhaps most, were directed by non-Americans. (Not that the homegrown talent couldn’t make a bad satire on America; see Roger Corman’s Gas! -Or- It Became Necessary to Destroy the World in Order to Save It, or the Monkee’s movie Head.)

Texan novelist and screenwriter Terry Southern specialized in this sort of material, often collaborating with foreign directors in bringing his jaundiced (and generally retarded) view of America to the screen. While he worked with Kubrick on Strangelove, his efforts sans the Maestro’s discipline were generally hideously bad. Southern’s novel was the basis of the epic misfire Candy (directed by a Frenchman), legitimately one of the very worst films ever. In fact, it seems amazing that Southern didn’t work on Englishman Michael Sarne’s legendary misfire Myra Breckinridge (1970).

It wasn’t just satires, either. Overstuffed and ludicrous ‘exposés’ of our racial climate was another popular topic for visitors to these shores to lecture us on. The Klansman (1974) was directed by a Brit, and starred one, too. Indeed, aside from the matter of directors, major English thespians also got into the act; actors such as Richard Burton (The Klansman), Michael Caine (Hurry Sundown; directed by Austrian immigrant Otto Preminger) and James Mason (Mandingo). Indeed, the ‘name’ star of this film, Rod Taylor, is Australian. (Hi, Lyz.)

On an odd side note, the only two even somewhat recent major studio films about the American Revolution were also helmed by imported directors. 1985’s Revolution was overseen by Englishman Hugh “Chariots of Fire” Hudson. Meanwhile, 2000’s The Patriot (which avoided the political dimensions of the revolution by depicting a man waging war against the British for personal motives) was directed by Roland Emmerich, a German.

In 1969, Easy Rider, a film the Hollywood studio establishment had basically viewed as a ragged home movie, made a gigantic amount of money. Confused by the film but hypnotized by its profits, the studios cast about for Young Artistes to make something similar. The problem being, since they couldn’t figure out Easy Rider for the life of them, that they had no basis for judging any of the pictures they hoped would repeat its success. All they could do was hope that the quite evident messes they were funding would, through some weird hippie alchemy, similarly tap into the Youth Movement Zeitgeist.

The results were predictably appalling, both artistically and certainly financially.* For example, Dennis Hopper, one of the stars of Easy Rider, was approached by Universal following that film’s success. Hopper grabbed a million of Universal’s dollars and carted all his friends to

[*This is not to say that the studio’s hopes in this regard were entirely wrong. Tom Laughlin made staggeringly huge amounts of money with his first three Billy Jack movies, including the legendary three-hour turkey The Trial of Billy Jack. Laughlin’s moment went as fast as it came, however. The tanking of his fourth trip to the well, Billy Jack Goes to Washington, effectively killed his career.]

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, like all the major studios, jumped in with both feet. For their part, they already had Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni under contract, and he still owed them two films. Antonioni was at the forefront of the modernist film movement, having helmed the existential ‘trilogy’ of L’Avventura, La Notte and L’Eclisse in his native country.

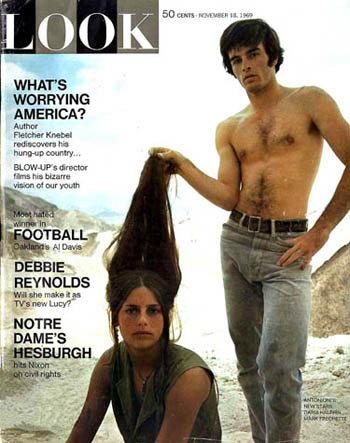

In 1966, Antonioni directed his first English language film for MGM, Blowup, which had been set and shot in England. The film was a critical and box office smash, the latter probably fueled by the film’s racy sex scenes. Antonioni was even nominated for a Best Director Oscar for the film. This combination of factors—his seemingly unassailable artistic credentials, previous box office success, trademark exploitable elements (i.e., sex and nudity) and the fact that he was already on contract and had already shot a film in English—undoubtedly made Antonioni seem a slam-dunk to produce a successful ‘youth’ flick.

Best laid plans, and all that.

We open in a large room, one packed with an assortment of Student Radicals (and, it must be said, realistically dorky ones) and Hippies. They are conducting a meeting, wherein they rap about Injustice and Taking It to the Man and suchlike. Because it’s a law or something, this sequence is shot in a highly fragmented style. The camera meanders around and offers forth a collage of Severe Close-Ups, all whilst the shots go in and out of focus. Ah, ersatz cinéma vérité. It provides all the calculation and artifice of a big budget studio film, yet seasoned with the technical incompetence of an amateur one, and marinated with several ladlefuls of rich, creamy pretension. Yum!

Meanwhile, the, er, credits unspool, with soft music playing on the soundtrack. To my admittedly unschooled ear, this sounds like a bongo drum tattoo mated with Moog synthesizer noodlings, random bits of incidental noise, and ethereal “Oo-ooo” scat singing.

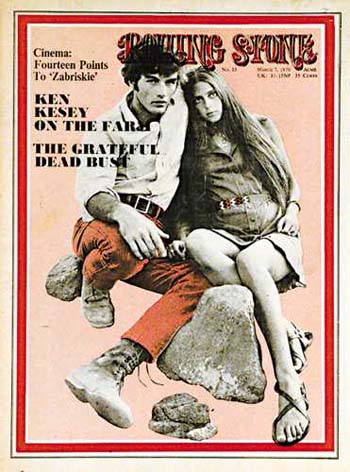

Indeed, Zabriskie Point may well remain better known for its soundtrack than the film itself. The bulk of the original score was provided by Pink Floyd, and other such luminaries as Jerry Garcia, The Grateful Dead, Patti Page (!), Kaleidoscope, and Youngblood also contributed. As I know (and care) very little about music, I’ll leave the explication and illumination of this aspect of things to Jabootu reviewer Pip Vandergeld, who in fact requested I write this review. Her thoughts can be found in the review’s Afterword section.

Per my introduction, the first two credited names we see associated with this scathing exposé of Amerikkka’s moral downfall are Italian; producer Carlo Ponti and director Michael Antonioni. Indeed, the latter received a possessory credit, although I doubt anyone much disputed with him for the honor. Mr. Antonioni is most often described as a “modernist” director, by which they apparently mean his films seldom attempt anything so vulgar or mundane as making linear sense.

The credits roll on. In an appalling breach of Hippie Movie Etiquette, we apparently are to be denied the stylings of one of the era’s notorious Improv Comedy Groups. (See Billy Jack, The Harrad Experiment). In compensation, however, we are threatened with alerted to the participation of an Improv Drama Group, i.e., the credited Open Theatre of Joe Chaikin.* We can tell this is an assembly of profound intellectuals and artistes, because they spell ‘theater’ with an ‘re.’

[*Hark thee, for thus sayeth Wikipedia: “The group’s intent was to continue [acting teacher Nola] Chilton’s exploration of a “post-method”, post-absurd acting technique, by way of a collaborative and wide-ranging process that included exploration of political, artistic, and social issues, which were felt to be critical to the success of avant-garde theatre. The company, developing work through an improvisational process drawn from Chilton and Viola Spolin, created well-known exercises, such as “sound and movement” and “transformations”, and originated radical forms and techniques that anticipated or were contemporaneous with Jerzy Grotowski’s “poor theater” in Poland.”]

The screenplay was provided by Mr. Antonioni, who as far as I know had never visited the United States prior to making this film. (Although to be fair, he had probably seen quite a few John Ford movies.) In order to help him understand the intricacies of the nation he was trashing, presumably, he is joined in this effort by four other writers, only two of whom were themselves Italian. Of the remaining pair, Claire Peploe was born in Tanzania, although she had apparently relocated to Italy at some point, since in 1978 she married director Bernardo Bertolucci. Meanwhile, the final remaining contributor was an honest-to-Jabootu American; playwright and actor Sam Shepard.

The meeting continues apace. Indeed, this ‘abstract’ sequence proceeds to eat up three solid minutes of screentime. I will admit, this didn’t exactly make me look forward to the nearly two hours of movie waiting to unspool. Eventually, however, the scene’s relative silence is shattered (wow!) by an Angry Black Dude, who is dunning the whites in the room with the aid of Another Angry Black Dude and, even more fearsomely, an Angry Black Woman. The first Angry Black Dude yells “That’s the same old jive we’ve, that’s running now for the past three hundred years!” Actually, as I have noted, it’s actually only been three minutes. Having also sat through them myself, though, I sympathize with the sentiment.

Impressed and all atingle to be sharing a moment with some Authentic Angry Black Personsâ„¢, the group’s overwhelmingly pasty-pale majority fervently applauds this outburst. Take that, Fascists! Then one wan white chick invites further instruction from her more Melanin-enriched superiors, suggesting that the group work to force the ROTC off-campus. Angry Black Man #2 has a suggestion in that regard: “Take a bottle, fill it full of gasoline, plug it with a rag…”

This suggestion is met with jeers from the more hippie-ish members of the assembly, whereupon I suffered several unfortunate flashbacks to the month-plus I once spent reviewing the Billy Jack series. Meanwhile, another young man responds with a line of dialogue that has been dubbed in with the sort of robust lack of technical expertise generally associated with Americanized Godzilla movies. “Yeah, man,” he retorts. “But what if you want to end sociology?” Ha! Who hasn’t asked that question during one all-night bull session or other?

One harbinger of things to come, and a main reason the film was met with so much disdain even during The Coming Age of the Revolution, is that everyone here is, uh, clearly not a professional actor. Indeed, they were all ‘real,’ because, like, you know, Art is Real, Man!! Screw your Uncle Fred’s bourgeois hang-ups about, liking, acting and scripts and stuff. Sure, you fascists might try to oppress the Enlightened Viewer with queries about why it cost $7,000,000 to make this film, then. And yes, to put it in context, that’s over five million more than it cost to make The French Connection a year later. However…SHUT UP, PIG!!

By the way, Harrison Ford is supposedly among the many dozens of people packed into this assembly hall. I think he may be the fellow with a heavy beard and blue long-sleeved shirt. Even if he isn’t, playing the cinematic alternate to “Where’s Waldo?” at least distracts one from paying attention to this scene. Sadly, after that I kind of ran out of ideas.

Watching events unfold, it becomes pretty apparent why The Revolution never came to be. It’s because whenever you assembled any group of self-labeled radicals, they invariably blew the entire meeting playing a vigorous round of “I’m More Authentic!“:

Authentic Angry Black Guyâ„¢: “Listen to me, a Molotov cocktail is a mixture of gasoline and kerosene. A white ‘radical’ is a mixture of bullshit and jive!”

Authentic Suburban White Chick Attending College on Her Fascist Parents’ Dimeâ„¢: “You know, I don’t have to prove my revolutionary credentials to you! You know, there’s a lot of whites who are already out on the Streets, fighting, just, just like you guys do in the Ghetto!”

Oh, and another reason the Revolution never happened? While the majority of attending white students sit there and takes the insults and jeremiads of the Angry Authentic Black Personsâ„¢ in stride…ah, the joys of self-flagellation…they also tend to politely raise their hands and wait to be recognized whenever they actually gird their loins enough to ask a question or attempt to deflect some particular piece of criticism. (“No, no, we’re the good white people! Like Leonard Bernstein!“)

This whole magilla goes on for another good long stretch. And I’m not kidding, you could cut ten minutes out of this, switch it with a nearly identical section from The Trial of Billy Jack, and no one would be the wiser. And that’s especially true if this hypothetical viewer actually tried to follow the rhetoric flying around these scenes. I can only quote from Adam Sandler’s Billy Madison, a film with rather more intellectual integrity than this one:

“What you’ve just said is one of the most insanely idiotic things I have ever heard. At no point in your rambling, incoherent response were you even close to anything that could be considered a rational thought. Everyone in this room is now dumber for having listened to it. I award you no points, and may God have mercy on your soul.”

During the assorted tirades, the angriest of which naturally are presented by the three Authentic Angry Black Personsâ„¢* (their status confirmed by their dashikis, clunky Malcolm X eyeglasses and humungous afros), the point is naturally made that if the attending whites are to indeed prove that they are radicals in good standing, they must close down the college until it is reopened according to their own demands.

Meanwhile, while loudly decrying (of course) the “Pigs” and the “Fascists,” Authentic Angry Black Womanâ„¢ boldly states that said obligations includes interfering with those other students who actually want to, you know, attend class and stuff, because “they in our way!” Yeah, that will show the Fascists, what with their goal of interfering with and attempting to control how other people live! (You know, there’s a lot to hate about the present Age of Irony, but…)

Things quickly descend into the inevitable shrill shouting match about whether violence should be used to shut down the campus. (Scenes like this, by the way, should serve to answer those who yet maintain that student radicals of the period were invariably non-violent). Finally, the ‘action’ is capped when Mark,* an Intrepid White Guy, stands and declares that he is ready to die for The Cause. If he’s lucky, perhaps this film takes place in the Billy Jack universe, where the Guv’ment was mowing down student activists by the hundreds.

[*In another indication of the film’s lust for Authenticity, Man, the names of the lead characters correspond to the non-actors playing them. Thus Mark Frechette plays ‘Mark,’ and Daria Halprin plays ‘Daria.’ Sadly, the film’s token professional actor, Rod “The Time Machine” Taylor—who MGM was no doubt praying would bring in a vast contingent of ticket-buying squares—was so caught up in his artificial plastic bring-down that he actually ‘played’ a ‘character’ with another ‘name.’]

Having said his brief piece, Mark splits. His fellow radicals consider this rude, presumably because they still have a full itinerary involving several hours of quoting Che Guevara and Chairman Mao to one another, before the ceremonial Smoking of the Pot and the shagging of unshaven hippie chicks.

“I guess meetings just aren’t his trip,” Mark’s roommate says by way of explanation. “Look man,” responds another fellow, who resembles a somewhat less-macho Sonny Bono. “If he didn’t come to join us, he shouldn’t have come at all!” (Uhm, I didn’t come to join you, either. Can I go now?) This sets off another bespectacled, doctrinaire nerd, who starts, and I kid you not, spouting off about Lenin and Castro. This in turn has one of the Angry Black Dudes going off about the Bourgeoisie, and really, what could I possible add at this point?

And so, nearly nine minutes into the film, we finally leave that room. And so we cut from These Earnest Idealists. (The ones planning various acts of revolutionary violence and who immediately expressed a profound loathing and suspicion upon witnessing even the slightest manifestation of individuality, I mean.)

We cut instead to a young woman presently being plagued by the forces of Petite Fascism. The victim is our eventual heroine, Daria. Dressed like a square in the chains of The Man’s fas[cism]hions, she is seen being thoughtlessly repressed by a *gasp* security guard—i.e., a thug in a uniform—who sits inside a monitoring desk in the sterile, marble-laden lobby of some Soulless Temple of Commerce or other.

Just to establish how repressive all this is, as Daria runs over to the security desk (presumably she runs as a sign of her Quiet Desperation), a *gasp* woman in a security uniform enters the shot. She’s older than Daria and not attractive, and hence clearly a part of the problem rather than the solution. She awkwardly hits her cue by stepping up to the main guard. “We had an open door on the third floor,” she stiltedly reports. “It’s secure now.” AN OPEN DOOR?! Why, The Man can’t allow that sort of thing! Open Doors allow people to escape!

Her moment of film immortality thus secured, the security woman walks out of shot. Daria then herself meekly approaches the first guard. He sits isolated inside his circular desk, seeming less a human being than a robot, a Cog in the Machine. (Wow!) Daria requests permission to go up to the building’s roof. As if parodying the Essential Life Force that the Idealistic Young Revolutionaries seen earlier so brimmed over with, the guard replies with a wooden shake of his head. He then mindlessly parrots the ominous phrase, “Company rules.” Yes, all tyrants rule. They rule by rules…wow, my head just exploded!

Daria explains that she had left a book up on the roof during lunch and would like to retrieve it. Of course, this display of independence is met with suspicion by the pocket Hitler before her. “What book?” he barks, puckering up his face. It’s true. The Running Dogs of the Establishment must perforce regard book-reading with hostility. After all, Daria might Learn the Truth, Awaken from her False Consciousness and Rise Up Against The Man.* You know, like in The Matrix. And look what that led to. The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions.

[*Or maybe he’s concerned that if she goes up to the roof and jumps off, the building owners will get sued and he’ll lose his job. Nah. It’s probably the repression thing.]

Still confused and angered by someone expressing independence of any sort—but angry in a bad way, not like the righteous anger of the Idealistic Revolutionaries earlier—he barks, “Why don’t you eat in the cafeteria?” Meanwhile, we cut to a seemingly pointless shot of one of his monitors, which shows two women walking down a hallway. It’s, like, they’re being monitored, man. DON’T YOU GET IT?! This is why he is so upset that Daria hasn’t been eating in the cafeteria. If she doesn’t go where she’s supposed to go, then how can they monitor…wow, my head just exploded again!!

Daria asks who can grant her permission to return to the roof. The Guard points to a screen monitoring the elevator—even the elevators are being monitored, man—in which rides Sleek Corporate Sellout Lee Allen (Rod Taylor). And while the guard’s been all dismissive and unhelpful with Daria, he rises obsequiously when Allen emerges into view. Yep, definite Running Dog. Oh, woe, Amerikkka. Woe unto you!

Noticing an Attractive Powerless Young Woman who his Corrupt Status might Allow Him to Exploit, Allen turns smiling to Daria. She explains how she left something on the roof during her lunch break. “A book!” the Guard warns. (See my prior note on books and such.) Allen asks if she does secretarial work. “It’s not something I really dig to do,” Daria admits. “I just work when I need the bread.” Ohmygosh, that’s exactly how The Man gets you! Despite being warned about the book and all, Allen is Arrogant in his Power, and deigns to give Daria the permission she seeks.

Cut to The Street. The camera pans over a large exterior mural of cattle; a shot I presume is Fraught with Significance in some manner or other. Along comes a dilapidated old pickup truck, driven by Mark and with his roommate at his side. As is often the case, they never bother (at least as I caught it) to mention the roommate’s name. I’m assuming he’s Morty, one of the few character names listed on the IMBD.

As they drive around, the camera begins a series of shock cuts to various advertising and business signs. I mean, you don’t know the meaning of being oppressed until you are innocently tooling along, minding your own business, only to suddenly find yourself assaulted by signage blaring “Ladewig Company Water Meters Valves.” It’s chilling.

During this extended montage (which oddly doesn’t feature any billboards advertising the latest movies), the soundtrack explodes with alternately grinding and percussive industrial noises. Some of these sound like screams or roaring beasts, others like gunfire. Oh, the Horror. The Horror. Meanwhile, two motorcycle cops ride by. Mark flashes them a peace sign, then goes to one finger after they have passed by. Way to Give It to The Man, dude! They also drive past a junkyard, which is also Symbolic of Something, I’m sure. Sadly, any hopes that Fred Sanford will make an appearance are quickly dashed.

I must admit that this takes place in a rather unattractive industrial area. If only Amerikkka offered other sorts of places for those as alienated as Mark to go. Perhaps the countryside? Yet I imagine these urbanites would react with similar discordant horror to an endless swath of rural pastureland. And the suburbs are, of course, all soulless and plastic and teeming with Hypocrisy and stuff. So where can you go? Where can you go to escape The Man? WHERE?!

Mark next drives through a palm tree-laden boulevard in what is presumably Beverly Hills or some similarly chi-chi location. Even as we’re barely recovered from the horror of the aforementioned barrage o’ signs, the camera rather jerkily pans to a traffic light up ahead that is just turning red. Mark, of course, is a Free Soul and Nobody’s Puppet. So he plows through the intersection, causing several other vehicles to brake and swerve to avoid hitting him. One young lady in a sports car, however, waves at him pleasantly.

Morty: “Who was that?”

Mark: “A girl from my long gone past.”

Morty: “What’s her name?”

Mark: “Alice. [Shrugs.] My sister.”

Dude, YOU HAVE OFFICIALLY BLOWN MY MIND!!

Morty pulls a form sheet from of his pocket and starts filling it out. He tells Mark that it’s a police report. “It’s an OR form, in case of a mass bust,” Morty explains. “They release you early if you fill one out in advance.” From this I assume they are going to a protest.

Mark frowns on the defeatism this implies. “Look, man, the day you don’t count on losing,” he replies, “is the day I’ll join the Movement.” “What if joining isn’t a matter of choice?” Morty retorts. “For lots of people it’s a matter of survival.” (Oh, brother.) Mark agrees that it’s not a game. “I’m tired of it, man,” he says. “Kids rapping about violence, and cops doing it. That guy at the meeting said people only act when they need to. But I need to sooner than that.” Yeah, it’s annoying the way the killing and arson and mass property destruction keeps getting put off.

They arrive at the campus, where students march around with signs and such. (Sadly, it wasn’t until decades later that progressive protesters learned of the importance of giant papier-mâché heads.) Morty is dropped off and Mark continues on his way.

We cut to a police station. The first people seen are some women clerical workers, who aren’t young or in any way attractive. Really, is that the sort of person you want to be? Mark shows up, asking the desk sergeant whether Morty’s case has been settled yet.

Whether it was the film’s intent, this does at least touch upon the play-acting element of all this. Getting arrested in this manner was a rather painless way for a student to get themselves some hipster cred. It was pleasing to the ego (“There I was, man, spitting right in The Man’s eye!”), and helped many score with the ladies. Better yet, the agitators knew going in that they’d be let out after an hour or two with few, if any, further ramifications.

Perhaps realizing this—although probably not—they attempt to make the ‘pigs’ look all, like, mean and stuff. When told to take a seat, Mark asks how long he can expect to wait. “Maybe five minutes,” the Sergeant snarls. “Maybe five hours.” Needless to say, we’re meant to marvel and quail at the rudeness the sergeant projects.

However, movies of this era seldom, if ever, told the story from the cops’ perspective. Imagine the endless task of arresting privileged, often upper-class punks for whom being jailed was a lark, then seeing them off on their merry way a few hours later. Meanwhile, you’re left facing mountains of paperwork and court appearances generated by this useless activity. No wonder the police seemed surly. I’m sure in fact some of them were brutes, but their side certainly had no monopoly on assholes.

Again, though, we won’t be seeing that side of things. (Or rather we will, albeit not where the filmmakers intended us to.) So Mark leaves, as we take a moment to have a Significant Look at a police helicopter lifting off next to the station. Then it’s back inside the police station, only in the booking area. A line of protesters stands against a wall, waiting to be processed. Morty is one of them, while another is festooned with an artfully bloody bandage.

The next fellow to be processed is a middle-aged sad sack in a bad suit and worse beard. As a cop types up his arrest report, he is asked his profession. “Associate professor of history,” the man replies. “That’s too long,” the cop barks. “I’ll just put down ‘clerk.'” I think this is meant to be an example of the ‘pigs’ being all insulting and dismissive. However, I suspect the cop was just embarrassed for the guy and sought to assign him a more dignified job title.*

[*I’m not into that whole red state / blue state thing, but I think you could probably separate into two sharply discrete groups those who think associate professors are more beneficial to society than cops—or clerks, for that matter—and vice versa.]

Meanwhile, the Professor is searched, manhandled and casually insulted by these retrograde Tools of the State, who naturally lack the empathy of this noble, socially conscious soul. “Some of these people over here need medical attention,” the Professor observes, bravely yet vainly attempting to Speak Truth to Power. His pleas inevitably fall on deaf ears. (And, no doubt, curly little tails.) “You didn’t say you was a doctor,” the cop japes, speaking with the sort of grammar you would expect from one of his barbaric ilk.*

[*Of course, when the black agitators mangle their syntax, it’s only because they’re throwing off the chains of the White Man’s language. So, you know, that’s completely different.]

Another bus load of prisoners arrive. (Again, that this might represent more of a hassle for the cops than the students doesn’t seem to have struck anyone.) Mark, seeing this, follows the vehicle to the back parking lot and attempts to enter the booking department through the rear door. He is warned off by a cop, but when he fails to comply, is himself arrested. Again, this is meant to be a Sign of Nazi-Like Evil, but seriously, what did he expect? Perhaps realizing this presents a rather lame Portrait of Oppression, the cop puts Mark in an unnecessary choke hold, thus furthering the film’s Searing Indictment of the System.

Mark is processed next. (What kind of a lesson is that? Making him wait in the back of the line would more sense.) When asked his name, he answers “Karl Marx.” All the students laugh, but the thuggish, uneducated cops fail to get the reference. (Oh, please.) Indeed, Mark is asked to spell Marx (!), and when the cop types the first name, it’s with a ‘C.’ The camera helpfully zooms in on the form as he types, to make sure we ‘get’ how dumb cops are compared to Idealistic Youthful Student Agitators.

Hardened by this Gross Perversion of Justice, Mark and a pal are next seen entering a massive gun shop.* They are told there is a four day waiting period, but are easily able to talk the salesman into breaking the rules. They do this by playing off the (of course) casual but deeply ingrained racism of the staff, by explaining that they live in a mixed-race neighborhood. “We’ve got to protect our women,” Mark tells the guy, who immediately falls into line.

[*I’m not into that whole red state / blue state thing, but I think you could probably separate into two sharply discrete groups those who think gun shops are more beneficial to society than ‘politically-engaged’ college students, and vice versa.]

The gun shop and its workers, of course, are meant to represent Bad Amerikkka, although not because they illegally expedite selling guns to dangerous young thugs. This jobbing of The Man’s rules, you see, is instead meant to establish Our Hero’s canny street smarts. See, Mark is using the Tools of the Reaction against the State itself. Get it? In any case, he and his friends leave with a couple of revolvers and a long gun.

Next we cut to a roomful of squares. They are all sleek-looking men in expensive suits, except for one woman who has a sort of mannish bull dyke vibe about her. Assuming that’s actually the vibe Antonioni was going for—and that certainly seems to be the case—then all I can say is “Nice.”

The group is vetting a TV ad for their company, the Sunny Dunes Land Development Company. The commercial touts a major new home development project in Arizona, and uses stylishly-clad manikins to portray the imagined happy homeowners. In case you don’t get it, the use of manikins is Fraught with Meaning and Symbolism. Most, er, tellingly, the camera keeps quick cutting between the posed, plastic manikins and the executives watching the ad. Man, what an ingenious artistic stroke.

We then cut to Allen in his car. This, unlike Mark’s rusty old Proletariatmobile, is all nice and stuff. (Boo! Hiss) As Allen drives around, news stories are heard on the radio, which conflate the (supposed) evil we were doing in Viet Nam with the (putative) evil The Man was performing right here in the good ol’ USA. For instance, there’s a story about homes being displaced by *gasp!* suburban sprawl. Like the Sunny Dunes Estates project Allen works on. See how it all ties together?

This item is followed by statistics of our soldiers killed in the War, and then a blurb on the arrests resulting from the still continuing campus demonstration. I suspect that in the longer director’s cut, there was also a news story about the erection of a new advertising signs for In ‘n’ Out Burger and a local locksmith. In any case, it’s all one big old Ball o’ Evil, I reckon.

Cut to the Authentically Low-Rent Digs of Mark and his roomies—no bourgeoisies neat freak these!—who are listening to the same news report. My, what a brilliant segue! My hat is off to Mr. Antonioni. It’s that sort of radical filmmaking technique which necessitated bringing him in from Italy to make this film, I guess.

Needless to say, while for Allen the radio reports were just background noise, their Evil Import is all too well understood by these Engaged Youths. Hearing that the authorities are about to step things up on campus, Mark heads over there for a look-see. First, though, he pauses to tuck a revolver into his boot.

Allen returns to work, walking past a Sinister Giant Computer Room. (Remember those?) I mean, it’s in a corporation, and the computer has all of these blinky lights and things, so it must be malign in some way. Then he pauses in front of a huge board that displays all the current stock prices. As a gag (I guess), the camera noticeably passes over the section of the board listing MGM. Allen enters the aforementioned board room and it is established he’s flying to Phoenix, the site of Sunny Dunes Estates, in a few hours.

We cut to a cloverleaf somewhere in the California desert, near a town called Desert Spring. This location is established via a nearby billboard, which, need I spell it out, is a large SIGN. I’m assuming this is on the way to the aforementioned housing project. Sitting in a car is Daria, who peruses a map before tossing it into the back seat and driving off.

Then it’s back to Allen. He enters his own mammoth over-decorated office, which sports a TV monitor running over what seem to be a series of clocks. Directly outside of the large bay window behind his desk flies a huge American flag. Boy, that’s some Subtle Art there, let me tell you. Getting on the phone, he tries to find out if Daria is still working in the building, as he’s apparently besotted with her. However, as we know, Daria has hit the road.

Allen learns this when he calls her home number and gets, well, some dude. The guy instantly displays his radical anti-establishmentarianism when he answers the phone by saying “Goodbye?” Then, when he’s about to hang up, he says “Hello.” Seriously, there was a time when somebody thought that was some sort of in-your-face political statement. Yeah, wow. Like, what if you went to some burger place, only then you ask the counterperson “What is your order?” Wow, I have now officially just BLOWN MY OWN MIND!

Cut to a weird, circular object. Pulling back, we see that it’s the bottom of a gasmask canister. The wearer of this, between his mask, goggles and helmet, looks more like a robot than a man. (Get it?) From this we pull back further to see a mammoth line of cops arrayed across the campus grounds. Milling close by are thousands of students. Pretty clearly, some of this footage was taken at an actual demonstration.

In some of the shots we see cops hitting protestors. Since fake footage is mixed with documentary stuff, I’m not sure what to make of this. We do see what look like some actual bloodied people, though. Even so, a little context would be nice. I know some cops beat on people with little or no cause. However, I also know that some students assaulted cops or committed arson and other criminal acts. Needless to say, we see little of that in these movies. Also, I can’t help noticing that these films all, some tacitly but most forthrightly, champion exactly the sort of confrontations that result in this sort of carnage. So…good job with that.

Mark trots around, gazing upon the stock footage demonstration in much the manner that Sabu looked upon stock footage elephants in Jungle Hell. Eventually he comes across the Black Radicals from earlier in the movie, now hiding behind a wall from some nearby cops. In doing so, they have left those they talked into ‘taking action’ to suffer the consequences. But, you know, although they themselves desperately crave to directly confront these Imperialist Running Dogs, well, you can’t allow the Intellectual Vanguard to come to harm. It’s only their solemn Duty to Dialectical Historical Forces that has them fiercely cowering in their current position.

Meanwhile, the cops call for the students still holding the adjacent administration building to surrender. When they fail to do so, a tear gas canister is tossed inside. As the students stumble out, one cop thinks he sees a gun. (Whether there actually is a gun or not is kept unclear from us.) In response, another cop shoots the student down. The student was black, by the way, and I can guess the inferences we’re to draw from that.

Looking to be in some sort of fog, Mark leans down to reach for his revolver, which remains below camera range. A shot rings out and a cop falls dead to the ground. Did Mark shoot him? We aren’t told, just as we’ll never know if the fallen student was actually armed. Art, you see, is all about Ambiguity. (Wow!) In any case, having struck this Blow for The People…maybe…Mark beats feet.

Our Hero takes a bus, er, somewhere. When he gets off, the driver portentously announces, “This is the end of the line.” (Wow!) Mark walks into a deli to use the payphone. He calls his roommate, and if you listen real close, you can hear Morty’s name being used for the first and probably only time, half an hour into things.

Morty excitedly warns Mark that his picture is all over the news. None too thrilled with this intelligence, Mark hangs up. On his way out, he tries to cadge a sandwich from the deli man, but naturally is oppressed by demands that he ‘pay’ for it. Sadly, if Mark lived in the sort of Socialist Utopia he no doubt dreams of, free deli subs and matzah ball soup would be widely available, as they were in Cuba and the former Soviet Union.

We cut outside, where Mark stares at a billboard blighting the landscape. Who’s the real criminal, I wonder; those who shoot cops, or those who put up ugly, ubiquitous signage…oh, wait. It’s the ones who shoot cops. Never mind. Anyway, then Our Disaffected Hero stares upward at a low-flying plane. Since he keeps looking at planes and helicopters, I think we can assume something of the like will come into play later.

More shots of billboards and signage. (Yes, we get it.) In one spotlit billboard for New York City, happy tourists beam as they gawk at the view from inside the crown of the Statue of Liberty. To our eye, however, the grill they gaze through seems like bars imprisoning them inside ‘Lady’ ‘Liberty.’ (Wow!) Meanwhile, Mark looks up again at the plane. (Yes, we get that too.) Then he wanders to a small airfield, looking over yet more small private jets. Man, that’s just dynamite filmmaking. Except for Coleman Francis, no director I can think of has so ably exploited the magic that is light aircraft.

Standing before a Piper Cub (or whatever), and after easily throwing off the only guy in sight—that’s some good security there—Mark clambers into the cockpit and, sure enough, proves to know how to fly it. And off he goes, much to the consternation of the staff in the flight tower. Noodling ‘rock’ instrumentals play as he flies to freedom. Er, I mean, to Freedom. Then it’s back to the desert, where Daria is driving around in her beat-up old sedan. It’s like she and Mark are converging on a Road to Destiny. (Wow!)

Next Allen gets a call from Daria, who’s now in some desert dive bar. She tells him she’s looking for a town she hears is good for meditation (if she wants to clear her mind, she should try watching this movie), and will be late meeting him in

[*Going back to the scene where the two ‘met,’ it really does seem like they’d never seen each other before. So I really don’t get why they now seem to have this sort of relationship all of the sudden. It’s like some hunk of the movie was excised prior to its release. On the one hand, it’s not like I want the film to be even longer. On the other, though, it would be nice if we could follow what is happening.]

Daria hangs up, then pauses at the bar for a beer and burger. She asks the owner (familiar character actor Paul Fix, veteran of about a billion westerns, cop dramas and TV episodes) where the meditating town might be. He says she’s in it. The barkeep is irked at the guy she’s planning to meet though, one Jimmy Patterson. Who, I should note, we’ve never heard of prior to now. I guess wanting a movie to make ‘sense’ just again illustrates my philistine hang-ups.

In any case, Jimmy apparently runs a camp or something for troubled kids—like the Freedom School!—and of course the redneck locals don’t like it. However, I can’t say I blame the bartender for his animosity. He no sooner says his piece then a rock comes smashing through a window, presumably courtesy of one of Jimmy’s charges. In fact, I’m not even sure what the film is trying to say here, other then I’m pretty sure it’s something Dire about America. I guess it’s that we abandon our kids to live in junk heaps and chickens come home to roost and that sort of thing.

Daria goes across the road to see what’s going on. She finds a gang of kids apparently living in a shanty town and running wild like something out of Lord of the Flies. One youngster sits and plunks out notes on the exposed strings of a demolished piano, presumably an example of a gentle artistic nature snuffed out by Brutal American Materialism.

Daria, venturing forward again, finds herself surrounded by a bunch of boys. At first she doesn’t take their sexualized taunts seriously, given their young ages. “Can we have a piece of that?” one lout asks. “Would you know what to do with it?” she laughs. She soon stops laughing, however, when they start grabbing at her in a sexual way. I’m talking about what looks to be a gang of ten year-olds here, and it’s a genuinely unpleasant and unsettling sequence. It also demonstrates that a mini-skirt is not a particularly good defense against this sort of behavior.

Daria, having more or less ascertained that Jimmy brought the kids here and then dumped them to fend for themselves, beats a hasty retreat. Then, after she drives away from the town, the camera peeks in the bar window to show an Unconcerned White Man sitting in placid isolation, ignoring the antics of the feral youngsters outside. See, it’s Fortress America writ large. (Of course, when we’re not isolationist, we’re imperialistic, so we’re really kind of screwed either way.)

Just in case we don’t ‘get’ that this latter fellow is an avatar for the willfully ignorant and disengaged Middle America, Patsy Cline’s “Tennessee Waltz” is heard playing in the background. You know, the exact kind of music that squares listen to. I mean, sure, Daria didn’t stay or try to help the kids either. And this Jimmy guy brought the kids out to the middle of nowhere and then apparently abandoned them. But that’s different. They are part of the Young and Beautiful Generation, and thus beyond reproach.

It should be noted that we’ve now officially entered that part of the film where it abandons any sense of ‘narrative.’ At some point in these things, you inevitably hit the Meandering Point.* From then on it’s all ‘incident’ and ‘symbolism’ and ‘deep social commentary,’ coupled with pacing that assumes a molasses-esque consistency. The idea being that it wouldn’t be ART if you pander to the audience by trying to ‘entertain’ it. From that standpoint, by the way…Mission Accomplished, Mr. Antonioni!

[*Note: The Billy Jack movies generally hit the Meandering Point about two seconds in, which admittedly makes this film seem like Casablanca.]

Back to Mark, flying over this selfsame desert. Because deserts tend to be really small, he naturally soon flies over Daria’s car. Being a playful scamp, he decides to repeatedly buzz her vehicle. (The stunt work here looks pretty dangerous, with the plane flying quite close to the car.) Needless to say, this puckish prank reveals not that Mark is a dangerous psychotic, but instead a free spirit. You know, like when he (maybe) killed that cop.

Anyway, during the actual buzzing, Daria naturally looks frightened and angry. This carries over when Mark continues to buzz her personally after she pulls over to the side of the road, leaves her car and lies down in the sand.* In response to this latter affront, however, she jumps up and writes out a message in the sand. We don’t see what this is (?), so I’m assuming it’s a more colorful form of ‘Up Yours!’ (I’m moreover assuming the presumed profanity was cut to secure the film an ‘R’ rating.)

[*You can’t say the cast wasn’t game. The actress playing Daria does her own stunt work here, and the plane really does fly only four or five feet directly over her.]

Mark answers by dropping a red marking sheet, or something, from the cockpit. Daria dutifully runs over, picks it up, and waves at the plane. Then she climbs back into her vehicle and continues driving. A few miles down the road, however, she sees he’s landed his plane to the side of the road. This discovery is marked by the sort of rambunctious country music you normally associate with the Bandit leading Smokey on another car chase.

Naturally Daria pulls over to go meet him, while assuming an interested, flirtatious expression. After all, think how cool his random terrorizing of her makes Mark seems. Not like that uptight square Allen. You don’t see *him* buzzing strangers’ cars with a stolen airplane. What a prig that guy is.

Daria returns the red cloth he through from the plane, which I guess is a nightie (?), and notes that she can’t use it. “Why not?” Mark quips. “Wrong color?” Or maybe they’re BVDs, since she replies, “Wrong sex.” Or it’s a sleeveless sweater. There’s a slogan on it, but the way the shot is framed you can’t read anything past “MEMBER.” It sure is freeing the way they’re ignoring the elementary and confiningly arbitrary rules of filmmaking, which can be shed like so many chains when you don’t care if the audience knows what the hell is going on.

Suddenly they’re at an old man’s desert shack. Or maybe that’s where Mark landed his plane. Frankly, I’m barely paying attention at this point. It sure is freeing the way the viewer can ignore the elementary and confiningly arbitrary rules about film watching, which can be shed like so many chains when you give up on trying to figure out what the hell is going on.

Mark asks Daria where she’s headed. She says Phoenix, and he replies, “Why? There’s nothing there.” The life of the party, that one. Since Daria has no destination in mind that Mark considers important, he says she may as well take him to get some gas for the plane. Of course, she finds his boorishness irresistible. Sadly, that’s not entirely unbelievable, even if the plane buzzing incident strains credulity a bit.

However, as a bit of flirting, she tells him about hearing on the news about a plane being stolen. “Did you really steal that thing?” she asks. “How come?” He smirks. “I needed to get off the ground,” he replies. She’s suitably impressed, and smiles. Boy, if he actually did shoot that cop, he’s like totally in. In any case, they pile into her car and drive off.

By the way, I really should pause to emphasize the fact that the two leads are not actors, and moreover, cannot act. There’s a difference between underplaying and not playing at all, as the stilted, deadpan ‘performances’ here pretty clearly establish. In this, the two are like all the various pals and hangers-on that Tom Laughlin would put his Billy Jack movies, although normally even he didn’t assign them lead roles. (Well, except for his wife and daughter.)

We’re now officially entered the ennui portion of the film. Shots of arid desert terrain are stretched out. Shots of Daria’s car driving down desolate desert highways are stretched out. And soon we get to the long section of the film dedicated to watching the leads cavort in these remote wastes. It’s totally groovy, man! This all lasts a while, since we’ve a full hour of movie left, and not overmuch to do until the film’s climax.

Soon, the kids arrive at a point overlooking a canyon. Daria reads from a granite tourist marker, and we learn they are at (are you ready?) Zabriskie Point. Wow, it’s the movie’s title! Zabriskie Point is, by the way, literally the lowest point in the country. As a metaphor it might be a bit closer to the mark than the filmmakers had been thinking.

They sit on the ledge, and Daria is all appreciating Mother Gaia and stuff, because you know…Wow! “How do these plants make it in the sand?” she wonders. Then she asks Mark about himself. We get a rundown of his rebellious acts, like “making phone calls on the [campus] Chancellor’s stolen credit card number.”

His big Act of Defiance, however—I assume we’re not supposed to know if he really did any of this or is just telling tales—was re-programming the Dean’s computer. To what effect? “I made all the engineers take art course,” he explains. (Dude, don’t even try and tell me that your mind has not now been OFFICIALLY BLOWN.) He passes over mention of the cop killing, though. You know, first date.

Daria interjects comments to prove that she also is Hip to the Scene. “Did you hear the Mexican Air Force is bombing grass on the border?” she asks. “I wonder what else is happening in the Real World?” Mark replies. He then slyly asks if she’s heard anything about the campus unrest. She explains that she prefers to listen to music. “It’s like they don’t even report it unless two or three hundred people get hurt,” he sneers.* Yeah, that’s what happens when you hold demonstrations every day of the week. They acquire that whole “dog bites man” feel. Er, wait, I mean, the Truth is being Suppressed by the Media Oligarchy!

[*”Two or three hundred“? And so does the film inevitably fall pray to The Trial of Billy Jack-level exaggeration.]

Mark does manage, however, to raise the matter of the cop being shot without rousing Daria’s suspicions. (On the other hand, she isn’t exactly Sherlock Holmes, if you take my meaning.) “Oh, a cop did get killed,” Our Heroine laughs. “And some bushes got trampled.” I’d again like to point out; these are the film’s identification figures. You know, the good guys.

Daria notes that the suspected killer is white. Mark laughs about a white guy killing the oppressors of the blacks. “Just like John Brown,” he says, tacitly comparing himself that that figure. Yeah, it’s exactly the same thing. And people wonder why I hate hippie movies so much.

Then they begin running around the pristine landscape (which I believe would be frowned upon now by a certain type of environmentalist). Again, you can’t say the actors weren’t game, because this includes the guy playing Mark running down a very high and steep grade. He kicks up a trail of dust to mark his path, rather like the Road Runner. Still, while the lady playing Daria may have been up—or down, technically—to having a plane fly directly over her prone body, she seems to have decided to skip this particular endeavor, since she suddenly just appears at the bottom.

Daria has fetched some weed from her purse, and she lights up. They indulge in a looong scene of hippie conversation (see IMMORTAL DIALOGUE, below), which is meant to make the chemical altered among us nods our heads violently on several occasions and shout, “Yeah, man!” Mark thanks Daria, meanwhile, for understanding that he’s on a Reality Trip [i.e., he doesn’t do drugs]. “It was nice of you to come with a guy who doesn’t turn on,” he says. “I’m pretty tolerant,” she shrugs. And there we have it, the definition of Hippie Tolerance: they’ll even hang out with people who don’t do drugs. Wow, it is like a utopia!

Mark and Daria walk through the landscape—and walk, and walk—hand in hand. “Pretend your thoughts are like plants,” Daria muses. (Oh, for the love of….) “What do you see?” I don’t know, somebody beating your head in with a rock? Oh, she’s talking to Mark. “A neat rose,” she continues, “like a garden, or wild things, like ferns and weeds and vines?” Mark, of course, thinks deeply on this provocative line of questioning. “I see a jungle,” he answers. (Wow!)

“It would be nice if they could plant thoughts in our head,” Daria natters on, “so that nobody would have bad memories.” If so, I could use some of that after I get done with this movie. “We could plant, you know,” she continues, “wonderful things we did.” (Seriously, where’s that rock?) “Like a happy childhood. Real groovy parents. Only good things.” Mark isn’t digging it, though. “Then we would forget how terrible things really were,” he carps. “That’s the point,” Daria heatedly retorts. “Nothing’s terrible!“ Mark finally begins to groove on her, like, totally radical vibe. “Far out!” he admits.

These are the people who were going to remake Western Civilization. As far as I can understand it, here was their carefully formulated plan:

Step 1: Tear down the existing order.

Step 2: _______________________

Step 3: Super Utopia, Baby!

We’ve been wandering around the desert for barely over five minutes now, which frankly gives me a whole new appreciation for Moses and the Israelites. On the other hand, they didn’t have to listen to these two natter away the whole time, so our experiences may be more equal than they appear at first glance. This is especially true given that there’s still no sign of this portion of the film ending any time soon.

More chatter. Mark hollers into the empty wilderness, and then stands listening to his own echo. (Now there’s an apt metaphor for this movie.) Daria, for her part, stands in place and twirls madly, like she was trying to turn into Wonder Woman. Fat chance, thinks I: Wonder Woman was both entertaining and interesting. Then she staggers off screaming in glee. Mark runs down more hills and does somersaults. Daria squeals in happiness.

Again, this ‘innocent’ behavior is supposed to make us like, and even more implausibly, admire these characters. And to be fair, it accomplishes that task better than the scenes of cop killing and grand theft airplane. At least I assume it does, although lacking an electron microscope, I can’t really say for sure.

Still, the film has mastered something. For just when I’m all but tearing out my own eyeballs to make all this cavorting stop, it does. Whereupon…we get back to the hippie chatter. Hostel has nothing on this movie, let me tell you.

Daria: “So anyway…so anyway…”

Mark: “What?”

Daria: “Soanyway oughta be one word. The name of some place. Or a river. Soanyway River.” [And…scene!]

Hard to believe this movie wasn’t a gigantic hit, isn’t it? It’s like a blackout sketch review from Hell.

And so on. They stand outside an abandoned mine. They examine gypsum crystals. Then…another sit and talk. Seriously, what the hell. WHAT THE FRIGGIN’ HELL?!!! Damn you, Pip Vandergeld!!

Eventually even this thing has to move on, and so we get to the scene that MGM was now doubt desperately hoping would sell this film: The sex scene. Please realize that back in the day, sex and nudity were still pretty rare commodities in American films. So much so that the presence of a European director alone was often a winking promise that for audiences that the picture would be a ‘dirty movie.’ MGM, however, left little to the imagination in this regard, selling this aspect unabashedly in the theatrical trailer.*

[*Portentous Narrator: “Zabriskie Point, where a boy, and a girl, meet…and touch…and blow their minds!“]

Needless to say, it’s a dragged out affair, so much so that it goes from honestly somewhat erotic and sexy to downright tiresome. Then we get to the element that made the scene forever infamous. As Mark and Daria first canoodle and cavort and then make love in the desert, suddenly they are surrounded by dozens of other couples (and trios, and foursomes). These additional participants are themselves frolicking and rolling around in the dust and (discretely) coupling, their ash-clad writhing bodies dotting the landscape.

What does it mean? Dude, seriously, like I’d know. Anyhoo, this goes on for over seven straight minutes of screentime. The scene offers forth a fair amount of nudity, if not a lot of action. And in case you’re wondering if it’s all as boring as it sounds, well, IT IS. Seriously, I cannot imagine what it was like being stuck in a theater with this thing, barred by the rules of cinema-going from just taking your leave. Again, I can only assume that a wide array of intoxicants came into play for those lonely souls who actually sought this movie out. For those who did, I hope the smattering of Ts and As afforded them at least some solace, no matter how goofy the manner with which they were presented.

Eventually somebody must have said, “Oh, yeah, the movie” and we get back to things. Not very exciting things, but things nonetheless. For instance, we cut away to see a pickup truck hauling a teeny trailer unit and a boat, and which is arriving at the spot where they left Daria’s car.

The people who get out of it are dumpy and middle-aged and wear bad clothes. Meanwhile, the camera zooms in at length upon the garish, touristy stickers that adorn their vehicle’s rear passenger window. This no doubt was enough to draw superior, self-satisfied chortles from the film’s target audience. The guy talks (of course) like a hick, and surveying all this natural beauty, opines that “Someone should build a drive-in up here!”

Then, having delivered this crass remark, he and his portly wife climb back into their Bourgeoismoblie and drive off. Thus is Middle Amerikkka exposed for the vulgar brute it is. Take that, Joe Sixpack! Writhe under the penetrating gaze of an Italian film director you’ve never even heard of, your sins elucidated for the amusement and edification of a bunch of pampered, smug stoners who’ve never done a damn thing in their lives!! Ha, ha!

Our Two Young Lovers, meanwhile, have made their way back to the road. However, Mark sees a police car, and scrambles to hide inside a roadside portapotty. Daria, getting that something is up, makes for the other, but is spotted by the cop. He pulls over, because…I don’t know, man. He’s a pig. He probably just wants to hassle somebody.

Anyway, Daria approaches his car, hoping to keep him away from where Mark is hiding. (He’s framed from below when we first see him, so his gun is emphasized in the shot. See, cops’ guns are bad.) Daria gets all sassy with him, which seems dumb, but maybe she’s trying to keep his attention away from Mark’s location. Of maybe she’s just Speaking Truth to Power or some crap like that. Whatever. Damn, isn’t this movie ever going to end?

Anyway, the cop reacts to her ‘wit’ with a look of long-suffering hangdog expression. Wow, what a fascist. Meanwhile, Mark leaves the port-a-john and draws down his gun on the cop. What a moron. As if he’d hit anything from that range with a snub-nosed revolver. However, the cop, unaware of his supposed peril, just climbs back into his car and drives off.

Daria, however, did notice, and runs over to chastise Mark. “Are you crazy?” she sputters. She also seems surprised to she the gun, although where he hid it during their recent, uh, exertions remains something of a mystery. Anyhoo, she asks if it’s loaded, and he says no, but then opens the cylinder and drops the cartridges into the dirt at their feet. (This actually seems significant concerning what happened to actor Mark Frechette a few years later. More on that in the Afterword.)

Daria puts the piece together and asks if he killed the cop at the protest. “No,” he answers. “I wanted to, but somebody else was there.” Again, you can see why this film didn’t do very well. For most people, this innocence-by-timing is hardly going to make Mark a more sympathetic, much less admirable, character. For the True Believers, meanwhile, this hedging on the character must have smelled like a sell-out.

Mark apparently also feels untested, however. Daria offers to help him escape—”If you cut your hair, they’d never recognize you”—but Mark has a plan. Here we cut to them, and they’ve paint Mark’s stolen plane in groovy colors. Where’d they get the paint? How long would this take two people? OK, three people, since the Old Man seen earlier apparently is helping. Even so.

The wings, by the way, are decorated with two giant bare breasts, while Mark is painting what might be a huge scrotum. Take that, Middle America!! “They might not even think it’s a plane,” Mark joshes. [Imitating newscaster] “Strange prehistoric bird spotted over Mohave Desert , with it’s genitals out!” The other two laugh, indicating the presence of some high-end pharmaceutical products. Meanwhile, the plane’s identification number has been altered with paint to read “NO WAR”. Chew on that, Nixon! (Actually, Kennedy started the war, although it’s weird how little attention that fact got.)

Daria is concerned with Mark’s plan to return the plane. After all, though, we’ve got to get to our tragic ending sooner or later. (Oops, sorry.) When she points out that he can skip the risk entirely, he replies, “I want to take risks.” Which pretty much sums up the film’s philosophy, such as it is. No matter how pointless or corrupt or counterproductive action might be, take a risk. Sadly, Mark Frechette followed this idea in real life, too. More on that later.

Cut to the propeller starting, over the painted face of a grinning, befanged pig (I think). Daria waves Mark him off, and in one of a number of beautifully composed shots—there’s nothing wrong with Antonioni’s eye, anyway—he lifts off and flies away. Then we cut to the airport, where a news crew and some cops are on hand, covering the robbery. In what I think is meant to be a humorous moment, the plane’s petite bourgeois owner notes, as he talks to a cop, that he had to paint the plane pink at his wife’s insistence. Then we cut to the plane in flight, with its new zany paintjob. Boy, what until she sees how it’s painted now, huh? Oh, my sides.

Meanwhile, the worker who let Mark take the plane admits to a TV reporter than he wasn’t actually convinced that Mark owned the plane when he let him take it. I guess this is meant to signal that he recognized, on some level, Mark’s moral and spiritual purity. I hope that consoles him when this on the record confession inevitably gets him fired, and hopefully sued by the plane’s real owner.

I was truly annoyed to see that there was still a half hour of film left, especially since in those days you couldn’t count on the endless end credits that eat up a lot of those clock now. However, I needn’t have worried. We now are treated to a protracted montage that cuts back and forth from Daria driving through the desert in her car, and Mark flying back to LA in his plane. Extended is not the word. This lasts, with one fairly brief cut back to the airfield, over four straight minutes of screentime. Four minutes of nearly nothing but shots of a car and a plane traveling along. That’s some gripping cinema there, let me tell you.

Eventually Mark makes it back to the airfield, and he does some crazy wing tilts and stuff to show off. When he lands, the number of police cars on hand (??) converge on his position. Mark taxis down and briefly ‘drives’ the plane around the tarmac. Then, for no apparent good reason, naturally, and despite the fact that the squad cars have his plane more or less boxed in, one uniformed cop rather needlessly opens fire on the plane. When they approached the now stalled vehicle, Mark is dead. Oh, the Humanity. Thus is Hope and Goodness snuffed out in our despotic country.

Daria hears this reported on the radio, and is predictably devastated. She stands on the side of the road (oddly already parked before the news blurb is even finished), stonefacedly heartbroken. Well, stonefacedly, anyway. Again, acting wasn’t Ms. Halprin’s strong suit. Then she begins to rock back and forth. Then she gets into the car and nearly turns around to head back to LA (I guess), before finally continuing on to Phoenix.

Daria eventually arrives at a huge and really quite gorgeous house situated up upon a red rock hillside. This is apparently the model home / headquarters for the prospective Sunny Dune development. The place includes a rather beautiful swimming pool, which is being used by several attractive, if presumably shallow and materialistic, young ladies. Daria pauses to listen to their empty chatter, then moves on, struck by the soullessness of it all.

She enters a little rock passage between the pool and the main house, and pauses under a little waterfall to dip her head in its purifying waters. No unnatural, chlorinated pool for Our Heroine; nosiree, Bob! (Although surely this is artificial too, right? You wouldn’t have cascading running water in the desert.) When she draws back her head, now dripping with water, she finally allows herself to shed some tears over Mark’s fate.

Inside the main house, Allen stands in short-sleeved casual ware, pitching the development to an investor. This collection of fat cats is being served drinks by a tired looking Old Black Woman. So there’s the oppression, right there. Plus, the room is decorated with hanging displays of guns. Oh, the Horror, the Horror. Allen is having a tough time of it at first.

Meanwhile, Daria continues to walk around the place, which is really beautiful, if ridiculously huge. I’m not a Homes & Gardens kind of guy, but wow. Meanwhile, the meeting takes a break. Wandering outside onto the extended terrace, Allen notices Dari and joins her. He sends her off to her assigned room to change her clothes, being so Wrapped Up in his Evil (I guess) that he doesn’t notice her sadness.

Downstairs, Daria sees another Oppressed Woman in White Starched Uniform, this one either Hispanic or maybe an American Indian. In any case, this wakes her from her fugue and she flees in horror. She dashes out to her car, and drives a little bit down the road.

Then she stops, and we get the sequences that really made the film famous. Or infamous. A small distance from the house, Daria parks and climbs out of the car. She then stars at the house, which represents (I guess) All That is Wrong with Amerikkka. The fierceness of her glare calls to mind such other great art films as Richard Burton’s The Medusa Touch or John Agar in The Brain from Planet Arous. And sure enough (although presumably only in her fevered imagination), the house and all its contents massively and spectacularly explode…for the next five plus minutes. I shit you not.

Presumably a great deal of the film’s giant budget was spent here. They built an entire one-to-one scale exterior model of the entire house, and blew it up. They shot from a large number of angles—it’s not like they were going to get a second chance at filming this—and we see them all. A huge mushroom cloud appears over the house, and we watch it explode again and again. Then we watch the interior stuff explode, in frenzied yet oddly detached slow-motion.

This sequence is amazing, and the slow-motion photography must have been, at the time, unprecedented and entirely stunning. Indeed, even now it’s quite impressive. We’re used to these sorts of pyrotechnics in the present day. However, this might have been the biggest movie explosion ever up until that time, and there’s no computer trickery at all. It’s all real.

As the sequence finally nears its end, we get some Pink Floyd music, which starts as subtle and hypnotic, and eventually becomes raging—the latter stuff calls to mind passages from the album The Wall, still nearly a decade off. However, as with almost anything, too much of a good thing proves, well, too much. By the time we see lovingly shot footage of a rack of clothes explode, and then (of course) a TV, and a refrigerator, and finally such hilariously cliché items as a loaf of Wonder Bread (!!!!) all exploding in exquisite detail, the effect becomes inadvertently hilarious. Frankly, my only question is how Antonioni could have possibly neglected to toss an exploding Coca-Cola machine in there.

In the end, I could only think of the Monty Python bit “Le Fromage Grand,” a skit about a French art film (all the funnier because it’s performed in French, with English subtitles) in which a disaffected young revolutionary and an emotionally distant young woman continuously meet in a series of junkyards. The woman always bears a cabbage, which represents Materialism. Eventually the two abruptly declare their love for each other, only to have the cabbage suddenly explode and kill them both.

The film is hosted by a hilariously pompous commenter, who occasionally breaks into the movie with ludicrously overblown analysis. I really wonder if they weren’t specifically poking fun at Zabriskie Point here: “Brian Distel and Brianette Zatapathique there in an improvised scene from Jean Kenneth Longueur’s new movie ‘Le Fromage Grand’. Brian and Brianette symbolize the breakdown in communication in our modern society in this exciting new film and Longueur is saying to us, his audience, ‘go on, protest, do something about it, assault the manager, demand your money back’. Later on in the film, in a brilliantly conceived montage, Longueur mercilessly exposes the violence underlying our society when Brian and Brianerte again meet on yet another rubbish dump.”

Satisfied with her again presumably imaginary victory (which in the end accomplished about as much as Mark did, and without anyone actually getting killed), a smiling Daria turns and reenters her car, whereupon she drives into the sunset. And then, finally, The End.

******

IMMORTAL DIALOUGE:

WARNING: THE EXTENSIVE DIALOGUE SCENE REFERENCED BELOW WAS NOT MEANT TO BE EXPERIENCED UNLESS UNDER THE INFLUENCE OF VARIOUS INTOXICANTS AND/OR NARCOTICS.

Daria: “Want some smoke?”

Mark: “You know you’re talking to a guy who’s under discipline?”

Daria: “What’s that?”

Mark: “This group I was in had rules about smoking. They were on a, uh, “Reality Trip.””

Daria, snorting: “What a drag!”

A Pause.

Daria, toking her reefer: “What do you mean, a “Reality Trip”? Oh, yeah, they can’t imagine things! Were you in with that group? Why didn’t you get out?”

Mark: “I wasn’t really in the group. I just couldn’t stand their bullshit talk. It bored the hell out of me. But, when it gets down to it, you have to choose one side or the other.”

Daria, her consciousness expanded: “There’s a thousand sides, not just heroes and villains!”

Mark: “The point is, if you don’t see them as villains, you can’t get rid of them.”

Another Pause.

Daria: “You think if we get rid of them, we’ll have a whole new scene?”

Mark: “Why not? Can you think of any other way we can go about it?”

Daria: “Who’s “we”? Your group?”

Mark, laughing: “You and me, babe.”

Another Pause.

Daria, surveying the Natural Beauty: “It’s peaceful.”

Mark: “It’s dead.”

Daria, laughing: “OK, it’s dead. So let’s play a Death Game. You start at one end of the valley, and I’ll start at the other, and we’ll see who can kill the most. We’ll start on lizards and snakes, and then move up to mice and rabbits. At the end, we’ll count up how many deaths each of us has. And the winner will get to kill the loser! [She notices Mark is not playing along.] Did I make a mistake? Do you not want to play that game?”

Mark: “I don’t want to play any games at all.”

And so on. And so on….

In the aftermath of passion:

Taciturn Mark: “I always knew it would be like this.”

Daria: “Love?”

Mark: “No, the desert.”

******

Re: The Music, or Pip Vandergeld Speaks:

Ken asked if there was a movie on his list of requestable movies that I would like him to review. I picked Zabriskie Point because of its genre, the free-love hippy days of yore. (After watching it, Ken said he’d like to punch me or something.) As I have waxed discordantly about before, I am the older daughter of two hippies, born as the overall movement was losing steam among the braying herd of Boomer sheeple. My folks were on the tail end of the scene, meeting in a Comparative Literature class my bio-dad taught at Morgan State and later living in a commune of sorts north of Berryville, Virginia, where my sister and I first blinked at the world.

It may not be apparent here, but I have a sort of contrarian’s nature. As I grew up (well, older, anyway) I was encouraged to break the chains of “European culture” thought to be smothering the pastoral loafer in us all and the “gender roles” thought to be restraining women. I took one look at the layabout refuse my folks surrounded themselves with and said “I want to play classical piano and get a professional degree and a career!” But I’ve always had a slinking fascination with the wide-eyed idealism of “intentional communities” and the bucolic frolicking these modern-day grasshoppers indulged in. Hence, my choice in the movie.

The Zabriskie Point soundtrack used to be one disc of music (or one record, for you oldsters). Later, when someone was really bored and they decided to wring a couple more nickels from the die-hard Grateful Dead and Pink Floyd fans out there, they released a second disc made up of Jerry Garcia and Pink Floyd cast offs. I will comment on both discs.

The first one starts off with Pink Floyd, who put out more albums and soundtracks before The Dark Side of the Moon than after it. Words of warning from a biased reviewer: Pink Floyd’s continuing popularity has always made me a little unhappy. To my ear, the band has always struck me as cynical, callous and cruel. I probably focus more on the lyrics than most of their fan base, who likely are floating in the clouds with David Gilmour’s breathless lisp and keening guitar or Roger Water’s tormented yowling. But under the Olympian production values and fret board heroics are paeans to beating your wife senseless just for kicks (“One of My Turns”), openly scorning their slavishly worshipful fans (“Have A Cigar”), murdering people in various ways (“Careful with that Axe”, “Murder”, “One of These Days I’m Going to Cut You into Little Pieces”, “Sheep”) and taking pleasure in stabbing people who trusted you in the back (“Dogs”). Success made me a scary, isolated narcissist! Pity me!

In any event, the first song is the aptly-titled “Heart Beat, Pig Meat.” It’s bad and dated, being a sort of a sixties version of the effect-laden atmospheric stuff that Floyd likes to start their CDs with. Voices fade in an out, there’s a “heartbeat” effect thumpin’ away, and a dated keyboard plays haunted house noises. There are no lyrics. “Crumbling Land” is the second Floyd track on Disc One and is significantly better. Sung by (I think) Gilmour with harmonies from the rest of the quartet, it is Floyd doing tradition ’60s folk, circa Crosby, Stills & Nash, with a psychedelic freak out at the end. It sounds like a more up-tempo version of “A Pillow of Winds” off the Meddle disc.

Tracks two and nine are from Kaleidoscope, a psychedelic folk band primarily active from 1966 to 1970. And that description says it all: they are right in the middle of that category—a band attached to a time and no other like A Flock of Seagulls or Nirvana. One mention of them to the folks starts an avalanche of Grandpa Simpson-esque reminiscing about a band that had largely folded by the time they had gotten into them. Track two is “Brother Mary” is classic stoner hippy country tune with fiddles and lyrics about a long-haired drifter. Just listening to it makes you want to get a job, even if you already have one. Track nine—”Mickey’s Tune”—is better, an upbeat instrumental featuring a fiddle on one side and a jingly guitar providing the other half of the melody.

Track three is also pretty good, being a 2½ minute excerpt from the Dead epic “Dark Star”—probably the single version, come to think of it. I went to a Dead show with family once somewhere in eastern Ohio; I was a little too young to remember anything except people dancing in circles.

Track five has Director Antonioni reaching for hip incongruousness by including the Patti Page standard “Tennessee Waltz” from 1950. We’ve all heard this, generally in the back seat on road trips with gramps at the wheel. Not surprisingly, her voice is the best single thing on this collection, just ahead of Jessie Colin Young (supra). Incidentally, it is the only piece in this collection I can play on piano.

Track six is “Sugar Babe” from the Youngbloods and is probably the best song on the first disc; you can really triple step to this at your friendly neighborhood barn dance. This is partially because of Jessie Colin Young’s vocals, among the best in the folk-rock genre, and the whip-smart rhythm section that stands up with that of Creedence Clearwater Revival, particularly on this upbeat country-rock standard. The Youngbloods were a natural choice for this soundtrack as one of the most-often cited “summer of love” groups and with their seminal hit “Come Together” and my favorite, “Darkness, Darkness.” (Aside: Check out the Cowboy Junkies cover of “Darkness, Darkness”; Brother Mary Dalton says to try the Robert Plant version.)