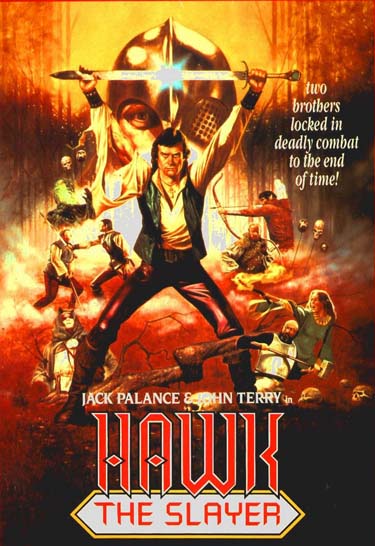

We open with a text card that apparently came from a discount bin “Fantasy Movie Software Pack.” It’s so generic, in fact, that I assume the instructions said you should personalize it in some way before using it, only no one bothered. It doesn’t help that after the card appears, a solemn voice begins reading to us the text right before our eyes, as if we’re so dumb we…would pay money to see a movie like Hawk the Slayer.

All right, never mind.

“This is a story of Heroic Deeds and the bitter struggle for the triumph of Good over Evil and of [run-on sentences?] a wondrous Sword wielded by a mighty Hero when the Legions of Darkness stalk the land.”

So, you know, when you hear something about magic swords and heroic deeds and Good fighting Evil, I’m sure you’ll invariably think of this movie.

In any case, our briefly-heard narrator—who sadly really isn’t up to the task, and makes one appreciate exactly how much an Ian McKellen or Richard Burton brings to the table—is clearly British. Fittingly, Hawk the Slayer was filmed at Buckinghamshire’s Pinewood Studios. It thus served as a precursor to the more lavish but equally lame Krull, shot there three years later. I ascertained this after checking on that very thing, when after four of five minutes of our current subject I found myself thinking unavoidably of that latter picture.

>While Hawk‘s smaller budget brings its own cheerfully threadbare feel to the affair, the fact is that the films are entirely too similar. This is particularly true in the way both pictures sacrifice several decent Brit actors (some of the same ones, in fact) in a woefully failed attempt to class up their respective joints.

The sad fact of things is that Krull‘s producers clearly did not strive hard enough to learn the lessons offered them by Hawk‘s manifold cinematic failings. Indeed, by larding on another ponderous half hour to their picture, they even failed to learn from the scant areas in which Hawk got things right.

Our film proper opens in some woods, with a man in medieval garb riding a horse. His metal helm and black clothes clearly mark him as a villain. Soon he arrives at an obvious miniature—sorry, I mean a castle—while comically generic ’80s-style music booms on the soundtrack. The complete score will entail several of the era’s most familiar musical tropes, including a heavy use of drum machines and synthesizers. On occasion, we even get some laser beam “PWEW PWEW!” sounds. An all too-inadequate bit of period-appropriate ass-covering, meanwhile, via use of the synthesizer’s “HARPSICHORD” function, only adds to the hilarity.

>What most caught my amused fancy, however, was the intermittent but unmistakable disco beat. The aggressively modernistic tone of the score (if little else about it) called to mind that provided the film Ladyhawke by Andrew Powell of the Alan Parsons Project. In that case, though, you could at least make an argument that it worked. Here…not so much.

Inside the *ahem* castle, the Old Man—that’s how he’s credited—stands in a chamber with the obligatory Mystic Pool (we can tell from the dry ice fog emanating from it, as well as the purple lights they’ve sunk beneath its surface), which is guarded by twin gargoyles. Fittingly, the gargoyles have been carved holding their heads in their hands, and thus project an entirely too understandable impression of vast boredom.

What most catches the eye, though, is that a presumably insane set designer apparently blew 15% of the film’s budget on gold foil and gold spray paint, with which every single square inch and object in the room, barring only the Old Man himself, has been coated. Presumably the intent was to project a feeling of opulence, in much the same way that a kid’s gumball machine trinket similarly adorned might suggest some lost, fabled possession of King Midas.

The aforementioned villain stabs a guard in the back, and makes his way into the chamber. He is Voltan (the top-billed Jack Palance), and as he addresses the Old Man, we learn that he is meant to be that fellow’s son. Even with the metal pot obscuring his entire head and half his face—due to some much-referenced but presently unseen disfigurement (thank you, Doctor Doom)—this is pretty humorous, given that the gnarled Jack Palance is all too obviously of much the same age as his ‘father.’*

[*In fact, the Old Man is played by genre vet Ferdy Mayne, most famously the head nosferatu in Roman Polanski’s The Fearless Vampire Killers, who was indeed but a spare three years older than his purported offspring.]

By the way, watch when Palance enters the chamber and shuts the door behind him. A pink, baseball-sized orb of what seems to be putty, perhaps something used to help hold the set together, falls through the camera shot after apparently being dislodged by the slamming door. Even if everyone somehow failed to notice this during filming, thus explaining why they didn’t reshoot the short sequence, you have to wonder why they didn’t bother to edit this out in post-production.

“The secret, Old Man!” Voltan demands, a sword pointed at his father’s chest. “I demand the Key to the Ancient Power!” (Man, they really spent a lot of time on this script, hashing out all the mystical details, didn’t they?) “The Ancient Power must never fall into the hands of the Devil’s Agents,” the Old Man responds. Indeed, you don’t want those guys getting 10% of it. They’re the ones who got Kevin Costner the lead role in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves.

Having either read his Joseph Campbell or seen Star Wars or a zillion other knock-offs thereof, the Old Man awaits his inevitable fate calmly. The moment soon arrives as the Old Man’s other son, Hawk, begins to pound on the door. Stymied, Voltan runs his father through and departs via a rather convenient back exit. Hawk forces his way inside, and except for a bit of sparkly flair adorning his vest, proves to be rather a bit too obviously modeled on Han Solo.

Needless to say, the Old Man has received the Expositor’s Mortal Woundâ„¢. This allows one to live however long is required to provide even the vastest amount of backstory information, only to then immediately expire upon completing this task. This, of course, is the direct opposite of the Failed Expositor’s Mortal Woundâ„¢, which kills a dying person the exact millisecond he is about to communicate some important bit of data: “The killer is…is…is…is AAAUUUGH!”

Dying, the Old Man avers “The prophecy’s fulfilled, my son!” This is the first and only mention of such a prophecy. However, you have to have a prophecy in movies like this, it’s a rule. The Old Man then gives Hawk a small leather pouch and tells him to take up the The Great Sword from its nearby wall bracket. I have to say, even given that Voltan has been successfully kept in the dark as to the nature of the Ancient Power, you have to be a pretty dense sort of adventurer not to grab something called The Great Sword when the opportunity presents itself. I mean, c’mon, that’s just common sense:

Dungeon Master: “You now enter a golden chamber, bare but for an ornately decorated broadsword hung upon the wall, spotlit by a roaring brazier. A plaque names it to be The Great Sword. What do you do?”

First Level Fighter: “Hmm. There’s no treasure?”

Dungeon Master: “Well, no, not as such, but…you know, the sign says The Great Sword.”

First Level Fighter: “Wait, is the sword made of gold or covered in rubies or something?”

Dungeon Master: “No, but…”

First Level Fighter: “Well, I’ve already got a sword, and it’s +1 against sandworms and Daleks. I’ll move on to the next room.”

Dungeon Master, mumbling: “14 intelligence, my ass….”

Following his father’s instructions, Hawk stabs the sword point down into the floor, so that it stands between them. This is unfortunate, as the hilt end of the sword is adorned with a carved, life-sized closed fist. Although we soon see why this is so, our initial conjecture upon viewing this is that The Great Sword was procured from Ye Olde Sexe & Fetishe Shoppe.

Hawk next removes a palm-sized rock from the pouch, which upon his concentrating upon it begins to glow a cartoonish green. The rock levitates into the air, the metallic fist on the sword unclenches—the camera first cutting to an angle safely above the ‘wrist,’ as we, uh, marvel at how this amazing piece of cinema wizardly was accomplished—and closes again after the brightly glowing emerald stone places itself in its embrace. Presumably this is a mystical rite that ensures the sword is so unbalanced that it can’t be wielded for crap.

Proclaiming the rock “the last, great Elfin Mindstone” (oh, brother), the fading Old Man commands Hawk to imagine The Great Sword in his hand. He apparently does, and the sword flies into his mitt, just in time to allow him to kill the yeti-like Wampa who…oh, sorry, wrong movie. (Actually, I’m sorry it’s the wrong movie.)

The Old Man says “The Mindsword is now yours, my son.” (Really? “Mindsword”? Whatever, dude.) Then, having reached the end of his scripted purpose, he kicks the bucket. Hawk mourns a good three seconds, and then turns to try out his spiffy new toy. It works as advertised, although I hope he learns to control it better later, because it takes about five times longer to fly into his hand than if he had just stepped over and grabbed the damned thing. “Voltan,” he cries—and wow, this guy is not a good actor, “you will die by The Sword!”

Cue credits, where for the first time the musical score really gives forth in all its cheesy glory, with the Buck Rogers in the 25th Century-esque ‘laser’ sound effects and the pounding disco beat definitely being the highlights. Moreover, we also get a flute solo that sounds like something a bleary Jeff Wayne wadded up and tossed away during a late night session composing his musical version of The War of the Worlds. Finally, just to really cap things off, the music’s presumably unintentional comic vibe is immeasurably multiplied by a very badly animated hawk (get it?!) that with no warning whatsoever suddenly appears screeching towards the camera.

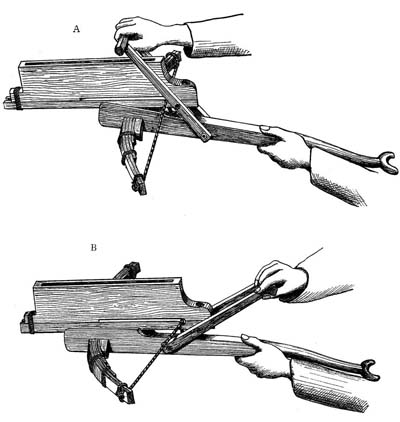

Credits over, we open on a wounded man, one equipped with a suspiciously machine made-looking metal crossbow, complete with pistol grip. He is crawling away from what sounds to be a battle of some sort, although this melee is kept strictly, not to mention economically, off-camera. He soon comes across a matte painting—sorry, I mean a Convent—and drags himself to the door. The nuns answer his knock and haul him inside.

The wounded man is Ranulf, as played by the too-good-for-this-movie William Morgan Sheppard, who nearly ruins the film’s general vibe with his expert underplaying. Sheppard is one of those actors you’re more likely to know by face than by name.

The actress playing the Abbess is rather too good for the movie. The scene the two subsequently share quite frankly seems like something from another picture entire, an impression deepened by the fact that it largely consists of Ranulf grimly describing the brutal massacre of his village. The effect is weird, as if they all suddenly thought they were making a film here or something. Luckily, however, Palance shows up before too long to set things a’right. (Or a’wrong, as may be the case here.)

However, we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Voltan is first seen standing outside a cave lit with crimson light, calling for a wizard within to aid him. “Enter, dark one,” bids the Dark Wizard (or so I assume from the credit listings), a rather silly-looking darkly robed and hooded figure who for some reason also sports glowing fingertips. (?) I hate to say it, but I assume he is meant to be the movie’s stand-in for the Emperor, just as Voltan is its Darth Vader.

The Dark Wizard stands before a big animated dot of red light, and during this sequence they’ve smeared Vaseline over the camera lens for an additional ‘otherworldly’ feel. As a final touch, the Wizard speaks in a whispery hiss processed through a voice synthesizer. All in all, the extremely goofy result most calls to mind the hilarious

Voltan bitches about how painful his face is, and removes his helmet in such a way that it draws attention to the fact that the damaged part remains off-camera. Given the amount of attention the film lavishes on his aspect, the inevitable Phantom of the Opera moment had better pay off, although clearly the viewer has little expectation that this will prove the case. In the meantime, the filmmakers continue adding zeros to a check that their artistic bank account can’t possibly hope to redeem.

The Wizard informs Voltan that his face is beyond all normal ability to repair, although his pain can be temporarily eased with “the

Voltan soon invades the Convent, accompanied by his grown son, Drogo. The performance of the actor playing Drogo, who apparently operated under the theory that hammy acting would be passed along in the genes, finally solves the mystery of what Sting thought he was doing four years later in Dune. Pretty clearly, it was this guy. In any case, Drogo could be replaced by a particularly bombastic Muppet with little noticeable effect.

Apparently the Abbess is a well known figure, and Voltan decides to kidnap her and demand a ransom from the Church coffers. This is actually sort of realistic, and thus completely out of whack with the rest of the movie. Once you introduce magical swords and Dark Wizards who lurk in caves, something as mundane as seeking a few thousand gold pieces seems entirely too humdrum.*

[*Actually, this all seems to be a Dark Wizard plot to draw in Hawk, who we are told stands in the way of his evil plan. Even assuming that’s true—and this really seems like one of those situation where if the villain had just ignored the hero everything would have gone his way—really, wouldn’t just sending him word of Voltan’s location bring him running? You’d think. In any case, the whole ransom thing is apparently just a ploy to burn off running time before the inevitable Final Confrontation.]

They grab the Abbess. When a barely recovered and now one-handed Ranulf attempts to intervene, he takes a knife in the chest for his trouble. Since any presumed damage from this pretty much entirely fails to manifest itself the next time we see Ranulf, I can only assume the point of this bit is to establish Voltan as a master of the throwing knife. Oh, and I’m sure you already assumed this part, but Voltan was the guy who oversaw the slaughter of Ranulf’s fellow villagers. In any case, Ranulf decides to travel to “the Holy Fortress at Daneford” to plead with the High Abbot for assistance.

So saying, the (again somehow unwounded) Ranulf is next seen galloping through the woods, before finally fetching up before an even grander—if no more convincing—matte painting. However, upon meeting the Abbot, Ranulf has it confirmed that Church edicts disallow the paying of ransoms, lest it establish a precedent. In lieu of this, the Abbot sends Ranulf forth again, now bearing a gold token that will ensure the assistance of Hawk (remember him?) when Ranulf finds him.

We now cut to Hawk, riding through the forest (oh, for Pete’s sake), which he proceeds to do for a couple of minutes. Hey, when you have some woods, some horses, and not a whole lot of money, well, do the math. Speaking of, and having already paid to rent the damn thing, they crank the fog machine up to 11. Here, and in much of the rest of the picture as well. Indeed, the movie The Fog barely had this much fog in it.

Hawk rides through the landscape. A further “unearthly” tone is set with mysterious bubbling in a pond, or at least mysterious to those who have never heard of dry ice. We also get to see a snake draped over a tree branch. As an Ominous Sign, this pretty much went out of fashion after the jungle movies of the ’30s, but there you go.

Meanwhile, the score here sounded like such a rip-off of the aforementioned Jeff Wayne that I actually checked the IMDB to ascertain whether he worked on the film’s music. He didn’t, of course, although the similarity certainly casts some doubt on how warranted composer Harry Robertson’s “original” music credit was.

One inevitably in movies of the Epic Fantasy (so to speak) variety is the Miscellaneous Adventures phase. The various films of this sort I’ve previously reviewed—Ator the Fighting Eagle, Wizards of the Lost World—have of necessity featured such an interlude. This portion of things presents a string of unconnected exploits, which are solely used to keep the hero busy until such a time as he can finally confront and kill the main villain without ending the film too early.

The problem, as one sits watching one dull, entirely random ‘adventure’ after another, and all while hoping and praying for the picture to bloody well get on with things, is the grim knowledge that this portion of the movie can, at least theoretically, last forever. Other than the fact that the producers will eventually run out of film, there’s no real reason this sort of thing ever has to end. After all, there can always be one more rubbery troll or haunted cave or Giant Muppet Spider or bewitching siren around the next bend.

And so Hawk naturally comes across some sort of Miscellaneous Injustice, in this case two chortling miscreants about to burn a supposed witch tied between two trees. Hawk calls for the men to stand down, a command they naturally refuse. One of the men fires an arrow at Our Hero, but at a thought (and some awkward editing) The Great Sword is in his hand, and he batters away the arrow in mid-flight. (!!)

Whether because their opponent has a magic sword with a big honking glowing stone in it, or more pertinently, because he has just seen the guy intercept a speeding arrow with it, the archer wisely beats feet. His friend, however, is more of a dumbass, and challenges Hawk after an exceedingly lame series of purportedly Leone-esque eye close-ups. Hawk quickly gets the better of the varlet and again bids him to depart in peace, only to be set upon once more. His hand forced, Hawk slays the fellow by, it seems, lightly running the blade along the outside of the varlet’s stomach. It’s a magic sword indeed!

Hawk frees the woman. She is both a Sorceress (conveniently enough) and blind, and so has Hawk lead her back to her cave. This is, it should be noted, a rather more modest affair than the one occupied by the Dark Wizard. Good guys, you know, aren’t all materialistic and stuff about their caves. Anyway, she naturally is employed to tell Hawk that he’s about to embark on a dangerous quest, and the final confrontation with his brother. She sends him off to intercept Ranulf, thus cursing the viewer with the illusion that the film intends to move things along swiftly.

Hawk is next seen riding his horse through the woods (kind of a motif, isn’t it?), and…UNMOTIVATED CLOSE-UP SHOT OF A LIZARD! Wow, that’s even cooler than the snake we saw before! Right, guys? Guys? Anyway, we then get a slo-mo shot of Hawk riding his horse through the woods, because there wasn’t enough footage like this in the film and they needed to stretch it out, apparently.

Proving I was on to something with this theory, they then layer different slow-motion shots of Hawk riding his horse through the woods on top of one another. Aside from being purely as cinematically exciting as it sounds, this apparently also inspired director John Derek, whose Tarzan the Ape Man came out the year after this. Assuming my now nearly 30 year-old (yikes!!) memories are correct, I seem to recall a, uh, battle between Tarzan and a big snake, during which the editor layered so many different slo-mo shots of the fight on top of one another that the whole mess soon become nearly opaque and impossible to decipher.

With (gaak!) an hour and ten minutes left to go, it’s again time to employ the Melville Discursion Engineâ„¢. So Ranulf is hailed by a pair of fellows in the woods—Ranulf was riding his horse through these, did I mention that?—and only his alertness allows him to put a crossbow dart into an archer preparing to ambush him. (By the way, I’m now getting a better look at the crossbow, and it’s not only clearly machined, but has a plastic pistol grip! Not since Ator’s medieval hang glider have I espied such a technological conundrum.)

Sadly, the other two varlets get the better of Ranulf. They knock him off his horse—which, lest the import of this has failed to sink in, means he cannot at this moment in time ride it through the woods—and tie him to a tree. They relieve him of his cash, and then decide to have some sport before finishing him off. This takes the form of throwing knives in his direction, to see who can come the closest without actually hitting him. Oh, the suspense!

Meanwhile, and I don’t want to shock the hell out of you, but we occasionally cut away to scenes of Hawk riding his horse through the woods…in slow motion!! And then—YES!!—shots of Hawk riding his horse through the woods in slow motion…layered upon one another!! Wow, this is like the greatest movie ever!

Anyhoo, the villains take turns with the knife-tossing, with the blades inching ever closer to their target. However, just in the nick (hmm, poor choice of words there) of time, Hawk appears and orders the two men to release their captive. I should note that this scene is completely different from when Hawk came across two men who had tied the Sorceress to a tree in preparation of killing her, because a) she was a woman, and b) she was actually tied between two trees. As you can see, the actual similarities between the two sequences are so slight that I’m not even sure why I bothered to bring up the whole thing.

Hawk and his two foes face each other in a triangle, and again the shade of Sergio Leone is evoked, although only if you squint really hard and repeatedly jab an ice pick in your ear. The two miscreants spread out, and after a *ahem* tense standoff, just when our nerves can stand no more and we risk falling into a catatonia of raw excitement, they go for their weapons. However, The Great Sword flies into Hawk’s hand, at which point he tosses it at one guy and impales him. (I don’t care how magic his sword is, that’s just retarded, because it’s clearly not weighted properly to be thrown in such a fashion.) Then Hawk grabs the other guy’s blade in mid-flight (!) and heaves it back, killing him as well.

Hawk frees Ranulf, and introduces himself. Ranulf, per the Abbot’s instructions, presents Hawk with the gold token. This ensures him of receiving Hawk’s aid, as well as a free game of Skee-Ball. It should be noted here that even in the few lines they exchange, you can readily appreciate the difference between someone who can act (the guy playing Ranulf) and one who cannot.

Cut to a realistically half-assed hovel of a medieval ‘tavern.’ Voltan is interrogating the innkeeper, as played by a barely recognizable Roy Kinnear. (And that’s true even if you’re the type of person who would normally recognize Roy Kinnear.) Meanwhile, Drogo, still camping it up like a Monty Python sketch, orders two nearby toughs to pay his father the respect he deserves.

Hmm, this is sort of instructive, really. Charisma is a difficult attribute to define. However, when Palance chews the scenery—as he surely does in this picture—he manages it with a weird sort of integrity. In contrast, when the guy playing his son tries it, it’s just comical. That’s the difference between a bonafide cult actor and just a bad one, I guess. Although to be fair, the fellow playing Drogo isn’t a bad actor; he’s merely out of his depth when acting this broadly.

In any case, the toughs don’t snap to with sufficient alacrity, and Voltan kacks one of them. When the other expresses his displeasure at this development, Voltan orders his tongue cut out. (Off-camera, thankfully.)

Back to Ranulf and Hawk. Here we learn that Ranulf’s crossbow comes equipped with a ammunition magazine and, moreover, has an automatic firing mode, like a machine gun. Why, yes, that is utterly and completely moronic. (As is the similar weapon used by the hero of Van Helsing.) Needless to say, no one else seems to have this technology, which would be laughably futuristic if it weren’t flat out ridiculous. How would this thing possibly work? Gunpowder provides the kinetic energy to not just launch a bullet, but to bring the next shell up into firing position. How would a crossbow do that?

And again, why is Ranulf is the only guy to have one of these things? Did he invent it? If so, isn’t that interesting enough to rate a mention? And shouldn’t such an extraordinary artifact get some sort of explanation? Also, did Ranulf use it when Voltan attacked his village? (It’s hard to believe he wouldn’t.) Wouldn’t such an advanced weapon have drawn Voltan’s attention? For that matter, wouldn’t Hawk display something other than a rather tepid curiosity at seeing it demonstrated? I mean, seriously, you can’t just stick something like this into a movie and not deal with any of the issues raised. Or, actually, I guess you can. You just probably shouldn’t.

Meanwhile, the movie makes the crippling error of occasionally trying to get all artistic on us. Here this involves a convoluted flashback involving Hawk, the woman he once loved, and the event that first caused strife between the brothers. We get this in spaced-out segments, as if it weren’t entirely obvious where things are headed during the first ten seconds of the first hunk. Instead, it’s slowly ‘revealed’ to us so that, when the shock twist climax of it all finally unspools, we will gasp at the way all the pieces have come together.

However, why should I spare you losers when I have to sit through all of it? The initial flashback opens In Happier Days, as Hawk and Eliane

In fact, let me try something here. Open up a Web connection…go to YouTube…let’s see, how about “Endless Love”…there we go…mute the sound on the TV and start the movie again…yep, it’s a perfect match. In fact, it’s downright friggin’ hilarious! Lionel Ritchie, is there anything you can’t do?

Anyway, the mood is broken when Palance enters the shot (unless, I suppose, you have very outre tastes in the romance department). So I turned off the video and, with a certain heaviness of heart, turned the sound in the movie back up. Anyway, Voltan still has his whole face here, and is madly jealous at Hawk ‘stealing’ Eliane, who he considered to be his woman. Voltan issues a warning and stalks off. Gee, I’m all on pins and needles. Where can all this possibly be going?

I guess we’ll just have to wait—I hope I can stand the suspense—as we cut back to the present day. Ominously, Hawk announces that he and Ranulf must now find some old friends of his, “Comrades who have fought at my side before.” Clearly this is where the dreaded Miscellaneous Adventures will come fully into play, as Hawk tracks down each of these in turn. “We have little time left,” Ranulf cautions. Sadly, though, at least according to the time code display on my DVD player, we have entirely too much time left.

My deepest, or at least dreariest, fears immediately come true when Hawk notes that, in order to assemble this band in time, the two of them will be forced to travel through the

“The shortest route is often the most dangerous,” Hawk explains. I don’t know about that, but it’s invariably the most boring. And sure enough, the two now set off, allowing for us to savor the sight of two guys riding horses through the woods and accompanied by a driving disco beat. Amazingly, though, they lay off the slo-mo here, probably because you don’t want to overuse such a powerful device. Once you have more than twenty or thirty minutes of it, you rather diminish its effectiveness. Better to save it for another five or ten scenes later on in the picture.

Soon they reach some trees that have been festooned with aerosol spray-on cobwebs and the sort of plastic skulls generally obtained in the Halloween decoration section of one’s neighborhood Target store. Then they approach a large, albeit probably Styrofoam, ‘stone’ gate that is just sitting there in the middle of the woods. They approach this, and magically disappear, an effect realized via the highly sophisticated Turn Off the Camera, Remove the Actors From Shot, Turn the Camera Back On technique. And except for the *cough* scarcely noticeable Background Stuff That Has Patently Shifted In Between Shots,* the effect is seamless.

[*Here’s a hint for budding filmmakers: If you’re going to employ this technique, don’t also put a big honking dry ice fog bank into the shot, because guess what, it will shift during the time you have the camera off.]

Warning that it is dark in the Forest of Weir—the better to hide the lame set-dressing, one might guess—Hawk intends to illuminate their way with the glow from his *snort* Mindsword. “Leave this circle of light,” he warns, “and I may be powerless to help you.” This almost makes it sound like something interesting is about to happen, although the unlikeliness of this is probably more apparent to those who have actually watched the movie so far.

So they ride past a bunch of fake webs, all mood-lit with the green glow from the Mindstone, as pre-recorded shrieks are heard. Hawk tells Ranulf of the three comrades they seek, who just happen to be, respectively, the very last Giant, Dwarf and Elf.* So all three races petered out at the exact same time? That’s weird.

He and Ranulf proceed through the forest, as the camera quickly (albeit not quickly enough) cuts elliptically away to some creatures that are obviously just a couple of hilariously bad hand puppets. I mean, these puppets are Rock ‘n’ Roll Nightmare bad. They make the titular puppet in Troll look like freakin’ E.T.

This goes on for about thirty seconds, and then…they emerge safely from the fearsome

[*When speaking of the Elf, Hawk describes him as, “An Elfin bowman from the

After riding through some more Halloween decorations, the pair arrives at the Sorceress’ cave. She demonstrates her awesome powers by lighting a candle merely by pointing at it. By this same logic, I could become a powerful wizard by buying the Clapper.

Anyway, she already knows of Hawk’s quest (ooooooh!). She will send him off through mystical means—which at least means a brief respite from the endless horse riding—and then the man he seeks may chose to return with him. That pain that you just felt in your head means that you have rightly deduced that we’ll now fart around for 15 minutes or so as Hawk seeks out each one of his three former companions, who obviously will all be introduced in some purportedly colorful fashion.

The ‘magical’ mechanism by which these journeys are achieved is a pair of shiny silver barrel-hoops conjoined at an angle. Frankly, it looks like an abstract sculpture of Mr. Pacman. Hawk sits inside this thing and it twirls around him accompanied by a silly sound effect, and looking rather like some oversized novelty purchased off the discontinued merchandise table at Spencer Gifts. Adding to the ‘awesome’ factor is that the rings are animated to glow in a succession of colors. The incredible majesty of this bit of special effects magic was summed up by our learned colleague Andrew Borntreger, who aptly described the result as “glowing hula hoops.”

Hawk first teleports off to seek Gort, the Giant. The guy playing Gort, Bernard Bresslaw, stands an impressive 6′ 7″, but I’m not sure that really qualifies him as being a ‘giant.’ On the other hand, the ‘dwarf’ we get later is Dudley Moore size, so maybe these things get exaggerated in the press.

Setting up his character, the genial but somewhat dense Gort is tricked into repairing the wagon wheel of Sparrow, a passing merchant, a task meant to demonstrate Gort’s immense strength. However, when Sparrows attempts to cheat him of his promised recompense, Gort retaliates by undoing his repair work. Although this takes place in an apparently isolated and remote forest clearing, six soldiers (of what army, exactly?) are conveniently on hand when Sparrow begins to squawk. Gort, wielding an immense war hammer, quickly puts them down, just in time to see Hawk standing in the inevitable dry ice fog cloud. He joins Our Hero, and they zap back to the Sorceress’ cave.

Sparrow, I should mention, is played by Graham Stark, a veteran comic actor perhaps best known as a regular presence in Blake Edwards’ films. Many scenes in the movie, in fact, present us with some well-known (to those conversant with British TV and films of the period, anyway) character actor, generally a comedic one. On the one hand, you want to applaud this general impulse, as it caters to the kick movie fans tend to get upon seeing a familiar face. However, in this case the impressive roster of actors is given so little to do that the effect is pretty much completely nullified. A for effort, but D for execution.

With Gort settled, Hawk whisks off to fetch Crow, the Elf. Wearing a red suede hooded affair, Crow is also sitting around in the middle of a forest, in a remote spot where an arrowhead-making blacksmith has set up his anvil. (?) Two disreputable fellows—are you starting to see a pattern develop here?—appear. One of the men, like Crow, carries a long bow, and naturally they mistake the lone stranger for an easy mark.

The glibber of the two, Fitzwalter (Christopher Benjamin), sends the blacksmith off on a fake task and then approaches Crow. To be fair, they actually attempt to draw these two with a bit more depth than most of the film’s gallery of miscellaneous characters. Fitzwalter is the talker, and as the cautious of the two, is the one who first feels they may be picking on the wrong guy here. However, his bowman partner Ralf is the inevitable arrogant hothead who brings disaster down on their heads.

When the talkative Fitzwalter doesn’t take the hint proffered by his silence, Crow doffs his hood. Because he is an Elf, he has a thin face, pointed ears and dark hair. Because he is an Elf in a bad movie with a limited budget, he looks like a Vulcan from somebody’s homemade Star Trek fan film. This aspect is exaggerated, moreover, by the director’s apparent instruction that the actor should talk in the manner of a five year-old impersonating a robot.

Fitzwalter takes the pointed ears as evidence that his doubts were justified. However, Ralf’s blood is up, and he won’t take no for an answer. He attempts to shame (I guess) Crow into a match by throwing an apple up in the air and spitting it on an arrow in mid-flight. I’m not sure why you’d demonstrate such skill if you’re trying to con somebody into a bet, but there you go.

Back in the game, Fitzwalter again goes into his patter. Crow remains aloof, but reacts angrily when Ralf fires an arrow down at his feet. Fitzwalter pacifies him, and upon seeing the color of the pair’s gold, Crow bows to the inevitable.

The contest involves shooting at a pair of cords tied around a distant tree. However, we soon see why the pair contrived to send off the blacksmith. As Crow bends his concentration to the task at hand, Fitzwalter moves behind him with dagger in hand. Crow is about to lose his “last of the Elves” status when, naturally, Hawk appears and dissuades Fitzwalter from his appointed task.

I should note, though, that is completely different from the time when Hawk came upon ruffians about to do in the Sorceress, and interceded to save her life. Or that other time when Hawk came upon ruffians about to do in Ranulf, and interceded to save his life.

Anyway, Hawk comes across ruffians about to do in Crow, and intercedes to save his life. Fitzwalter backs away from Hawk’s sword, and the archery contest continues. Inevitably, Ralf nicks one cord without quite parting it, while Crow’s arrow completely sunders the other. Ralf reacts badly to losing, and of course demands a duel. He and Crow face each other, bows in hand. Before Ralf can even nock his shaft, however, he is impaled by his opponent’s arrow, leaving Crow triump…OMG, I FORGOT TO GIVE A “SPOILER ALERT” ON THAT! I’m so sorry! I hope I haven’t ruined the movie for you now.

Back to the cave. I just noticed that when Hawk and Crow make their sudden appearance there, Hawk is still inside the Magic Hula Hoops, while Crow is just sitting off to the side. So…what, they couldn’t afford two sets of rotating barrel hoops?

As you may have imagined from my general description of all this, this section of the film somehow manages to be both still goofy as hell and yet extremely tedious. The goofiness, meanwhile, is not exactly assuaged by the woman playing the Sorceress. First, she speaks in an irritating whisper—because, you know…the Spooky…while over-annunciating her lines. Her H’s in particular are overly stressed, so that every time she say “Lord Haaawk” it sounds like she’s trying to (no pun intended) hawk up some phlegm.

Her appearance is little better, and fails at the evident attempt to make her all mysterious and stuff. She wears a hooded shawl, while her eyes are covered with a wide headband imprinted with a drawing of an eye. It’s sort of like a medieval version of when Curly Howard used to paint eyes on his eyelids so that nobody would know he was sleeping. Frankly, I had to wonder if it wasn’t the actress who herself suggested that she whisper and have her head and face obscured. If so, actress Patricia Quinn, better known to cult movie fans as Magenta from The Rocky Horror Picture Show, never counted on the All-Seeing Eye of the Internet Movie Database. Ha, ha!

Oh, anyway, on to finding Hawk’s last comrade, Baldin the Dwarf. We cut to some ruffians about to do in Baldin, whereupon Hawk intercedes to save his life. Baldin is *groan* the film’s Odious Comic Relief. (In this case, he’s literally odious, in fact, being a right little dirt bag.) How unfunny is he, you ask? Remember how borderline unfunny Gimli the Dwarf was in the Peter Jackson Lord of the Rings trilogy? Well, Gimli was in Lord of the Rings, and Baldin is in Hawk the Slayer. You do the math.

Since Baldin is the ‘comic’ relief, his predicament is ‘humorous.’ He’s tied to a raft floating in a small lake, the prisoner of a daffy religious cult. The head Priest of this is, sadly, played by actor Patrick Magee, veteran of a zillion Brit horror pictures. If Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee are sort of modern British analogues to Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi, then Magee would be their George Zucco. In any case, I’m sorry he couldn’t find a paycheck elsewhere. For his part, though, Magee wisely had obviously decided to partake of the film’s extensive scenery buffet, given the enthusiastic masticating he performs upon it.

Anyway, in order to “purify” Baldin, Magee’s acolytes will shoot flaming arrows at the raft, and Baldin will go down with the ship, as it were. Believe me, the movie and certainly those watching it would be better off if they had succeeded in their task. However, as noted, Hawk appears and screws the whole thing up. Thanks a lot, jerk.

Baldin, you see, is the group’s zany, wisecracking con man guy. He alternates between making pleas and hurling insults, and is, I think I can honestly say, equally funny in either case.

In truth, Baldin frees himself from the ropes binding him as soon as Hawk appears, so I’m not even sure what the point was. Maybe this was supposed to be ‘funny.’ Since, in fact, it is not funny, that’s actually a pretty good bet. Oh, and when Baldin jumps off the raft and into the lake, he holds his nose. I hope you don’t crush your knee into a fine powder with all the slapping thereupon inspired by that hilarious bit of drollery.

Giving us a display of his mirth-inspiring grossness, Baldin fetches a fish from the lake with his trusty whip (!), and proceeds to eat it raw, head and all. Oh, what a scamp that one is. Apparently it was beyond those making this film to procure a fake fish made out of something edible, however. So instead the camera rather lamely cuts away just as

And so back to the cave once more. Hawk is seen quickly filling his team in on their mission and the perils they will face. “Remember, Voltan has many men….” he claims. To be fair, he may just have a different definition of the word ‘many’ than I do. However, his old comrades, faced with being the last of each of their respective races—again, that seems a tad unlikely—all embrace the idea of a final adventure.

The Fellowship’s first task is to procure the ransom Voltan has demanded. Since they know he won’t honor his agreement, this seems somewhat pointless. However, there are still nearly fifty minutes of running time left, and they have to do something, I suppose. Even in this film they can’t just cut to thirty straight minutes of men riding through a forest in slow-motion. (I hope.)

The Sorceress alludes to a hunchbacked slave trader previously mentioned in the film. Since all of Our Heroes are enlightened on the issue of slavery—weird for the time period, maybe, but there you go—they decide this would be a fitting place from which to get their funds.

First, though, Hawk has another flashback to the mysterious tale of what could have possibly happened to the woman he once loved, and to the unguessable source of his feud with Voltan. Romantic music plays in the background as Hawk and Eliane stroll through the woods. They express their deep and abiding love for one another as music, perhaps provided by the less talented brother of Zamfir, Master of the Pan Flute, plays in the background.

However, their declarations are interrupted by a mysterious figure in black, who steps into shot and levels a crossbow at them. WHO COULD THIS MYSTERY FIGURE POSSIBLY BE?! WHAT WILL TRANSPIRE AS THIS TALE CONCLUDES?! However, the solution to these questions is again denied us, as the flashback ends. I’m on the edge of my seat, though, let me assure you.

With this, we bid farewell to both the Magic Hula Hoops and the Sorceress. Goodbye! We’ll never remember you!

We cut to the Fellowship riding through the forest. They spare us the slo-mo this time, although they do crank up the disco-inflected theme music. At one point, we see that Baldin, being a dwarf (sort of), is riding a donkey instead of a horse. If I had to hazard a guess, I’d say this was meant to be funny, although I’m not sure why. And also, where did they get these animals? The three companions were teleported onto the scene. Were steeds, saddles, bridles, etc., really that easy to procure in those times?

The Fellowship returns to the Convent, where they are greeted warmly by Sister Monica and the rest of the nuns. However, Sister Monica is aghast to learn they do not have the ransom yet, and flies into a hysterical tizzy each time Our Heroes opine that Voltan intends to kill the Abbess even after getting the ransom, and that their only recourse is to fight him. We get numerous scenes to this effect, to the point where you just want them to start slapping Sister Monica around. Were she around today, she’d no doubt be putting her faith in the United Nations to peacefully resolve the matter.

Anyway, Hawk’s assurance of Voltan’s perfidy segues into the next part of his ongoing flashback. (By the way, isn’t it weird for somebody to flashback to a central event of their life in chapter format?) It turns out—and I advise you to sit down before reading this explosive revelation—that it was NONE OTHER THAN VOLTAN who was the mysterious figure with the crossbow seen earlier.

Anyhoo, we join the action next to a lake, with Hawk now tied to a tree. (People tied to things being right up there with people riding horses in this picture). So not only are his flashbacks presented in segments, but edited for our convenience as well. A raving Voltan (Palance really goes to town here) tortures his younger brother by putting a crossbow bolt in his shoulder. However, Our Villain has underestimated the Princess Eliane, who retaliates by shoving a blazing torch into his face. HEY, THAT EXPLAINS WHY HE KEEPS HIS FACE COVERED! IT’S ALL COMING TOGETHER!!

Sadly, although valiant, Eliane is none too bright. Rather than taking advantage of the opportunity to kill the writhing Voltan, she (accompanied by some especially bad music) instead hurries to free the half-conscious Hawk and manhandle him into a nearby boat. Before they can get to safety, however, the anguished Voltan manages to fire another crossbow bolt. This strikes and kills the fair Eliane, in slow-motion, of course, and leaves Voltan horribly disfigured and his brother bereft and vengeful. Wow, that story explains a lot, doesn’t it?

Rousing from the (thank goodness) conclusion of his serial reminiscence, Hawk assures Sister Monica of Voltan’s ill intentions. Indicating that she was perhaps a distant ancestor of Neville Chamberlain, Sister Monica will not brook such an idea. “He gave his word,” she insists, continuing to insist that the paying of the ransom will ensure peace in their time.

However, as Sister Monica suppresses her own fears, our worst ones are realized as we move on to an extended bit of ‘comic relief.’ A Sister brings the men a platter of roasted chicken and potatoes*—pretty fine fare for a medieval Convent, actually—and Gort says, “That will be sufficient for me. Please bring some food for my friends.” See, he’s a giant (kind of), and he eats a lot. HA HA HA HA!

[*Proofreader Carl Fink provides this produce puzzler: “Potatoes are from Peru. In Medieval Europe, no potatoes, they didn’t get to the Old World until the middle to late Renaissance. This is right up there with Ator fighting Samurai.”]

However, the hilarity doesn’t stop there. (No matter how much we may pray it does.) Baldin, being a crafty rapscallion—a prime example of Ye Olde Implied Attribute—makes to con the slow-witted Gort out of his comestibles. Given that they are supposedly old associates, and that Gort has presumably been scammed many times by Baldin in the past, he yet proves a suspiciously easy mark. The scene ends with a dubiously glowering Gort watching Baldin scarf down his chicken.

We cut to the, uhm, camp of the Hunchback, who we can instantly tell is a miscreant because a) he’s a big fat disgusting slob who dribbles food out of his mouth when he eats, b) is a hunchback, and c) wears an eye-patch. He also casually wields a big iron mace that would weigh 50 pounds if it were real. Some customers appear to look over his wares, which amount to around eight suspiciously well-fed white guys in loincloths.

This leads into our first legitimate battle (sort of), as Hawk confronts the Hunchback and his dozen henchmen. Hawk coolly demands the Hunchback’s money, and needless to say, a melee (kind of) results. It’s really not much of a fight, though. Crow the Elf has the magic ability to fire arrows at a fantastic rate—an ‘effect’ realized by repeating the same shot of him shooting an arrow in quick succession—and of course Ranulf has his machine gun crossbow. Not very sporting, you’d think, but there you go.

In this manner, the two of them quickly account for, by my count, about twice as many guys as the Hunchback had in the first place. With all the henchmen—and more—quickly slain, Hawk orders the slaves freed while Gort collects the gold. Our hero even tosses a bag of gold to the freed men, thus ensuring that their village will have such an inappropriately huge amount of money that bandits will surely raid it and kill everybody.

The Hunchback, meanwhile, is left to Gort’s tender mercies. The end result is that the Hunchback is tied to the ground with his own huge mace suspended high over this head, held aloft by a rope the end of which is secured by having the Hunchback bite down on it. The scene ends when (off-camera, thankfully) the Hunchback can not keep from issuing vows of revenge, and the mace plummets. “Some people can never keep their mouths shut,” Gort quips. A regular Oscar Wilde, that guy.

We cut to Voltan’s tent, where Drogo, who seems to suffer from a Daddy complex, is requesting permission to raid some northern lands. Voltan refuses, being obviously aware that Drogo is an inept, blustering numbnuts. I fear the scriptwriters had the Dauphin from Shakespeare’s Henry V in mind when writing Drogo. If they actually made that comparison themselves, they should be severally slapped for a good, long while. On the other hand, it explains the exaggerated acting technique of the guy playing Drogo, who indeed seems like he’s trying to project out to the cheap seats.

Voltan denies his son with a violent display, of course, meant to demonstrate how deadly a Real Man is. Drogo is throttled and tossed on the floor, and Voltan turns his back in disgust. Tired of being humiliated by his pop, Drogo begins pulling his knife from its sheath. Without looking around, Voltan promises to kill his son himself should that dagger be drawn another inch. Needless to say, Drogo wimps out and runs away.

Later, Drogo is (everyone together now) Riding Through the Woods when he comes across one of Hunchback’s would-be customers. Drogo is pleased to find easier prey to prove his manhood on, and threatens the fellow. The latter attempts to bargain for his life, and more, with the information he has on the Hunchback’s demise. He describes the warriors who killed the slaver, and and of hearing mention that they were staying at the Convent.

Realizing that the man speaks of Hawk, Drogo naturally pretends that he will reward the fellow, but instead kills him—oops, sorry—so that no one else will have this intelligence. I doubt I have to spell this out, but his plan is to prove himself to Daddy by killing Hawk himself and bringing Voltan the gold. “We’ll see, Voltan,” Drogo mutters portentously, “who is the Lord of the Dance.”* (??) Three guesses how this all turns out.

[*What, you were expecting a Michael Flatley joke? Please. How juvenile do you think my sense of humor…. OK, never mind.]Meanwhile, Voltan has again repaired to the cave of the Dark Wizard, seeking temporary respite for his face, which we still haven’t seen. Wow, the suspense. The Wizard again employs the Goofy Glowing Crystal to shot little animated bolts at Voltan’s face. I mean, surely they could have come up with a better idea than that? And considering how much agony the process causes Voltan, you wonder why he bothers in the first place.

Back to the Convent. With the money in hand, Sister Monica is again luxuriating in the fantasy that soon all will be well. She again freaks out when Hawk and the others continue talking about Voltan’s untrustworthiness, and tries to order them to leave. Obviously, though, she doesn’t really have any way to enforce this edict. Ignored, she leaves in a huff.

Hawk orders Baldin to determine how defense worthy the Convent is, leading to—and I’m not exaggerating—a literally fifteen second reconnoiter. Following this extensive survey, Baldin reports on the single side door he peeked into and declares the Central Chamber (which pretty much comprises the entire Convent set) “is as you see.” Good job! I can see why Hawk wanted these savvy, war-hardened veterans at his side. This bit of business concluded, we segue into another ‘humorous’ scene with Baldin scamming Gort. I’ll spare you.

Meanwhile, Drogo is leading a mighty force of, uh, maybe eight or nine guys to the Convent. You’d think a despotic, marauding warlord like Voltan would have some horses or something, but the guys are on foot. Because of this, they don’t arrive at the Convent until that night. Crow, on watch, hears their approach, probably because of the pointed ears.

He reports to Hawk. Sister Monica again begs them to just hand over the gold and end this all peacefully, a plot device that is increasingly wearisome. Hawk sends the sisters off, and his men place themselves in positions of ambush as Hawk himself stands in plain sight. Drogo, with his *cough* dozen men, throws the door open and strides inside.

Hawk tells Drogo to run off and tell his father he can have the ransom when he returns the Abbess. “I am no messenger!” Drogo sneers. “But I will give you a message! [??] A Message of Death!” (Wow, that kid clearly needs a speechwriter.) And so a melee begins, and soon everyone is crossing swords and war mallets and whatnot. Meanwhile, Crow and Ranulf again employ their rapid-fire weaponry to decimate far more men than Drogo had brought with him.

Most of the men (and more) are quickly dispatched, with the remaining pair bade to return the severely wounded Drogo to Voltan’s camp. Then Sister Monica once more runs out and bitches about how they didn’t just hand over the gold. Seriously, we get it. She’s an idiot. Point taken. Move along, please.

The lackeys bear the dying Drogo back to camp, setting up a big Hamola scene for Palance, which naturally he takes full advantage of. (Although his supposedly bereft cry of “DROGOOOOOO!!” is laughably bad.) “My son lies dead!” he hisses, and I couldn’t help but think of Lear mourning Cordelia, which was rather similar but with a lot less sucking. To assuage his grief, Voltan cuts down the men who brought his son back. Perhaps it was the only way to get out of tipping them.

Back to the Convent, where Hawk’s crew is again (still?) dining from the place’s weirdly well-stocked larder. Seriously, where are the Sisters getting all this prime grub? The Fellowship is pensive. “The gold is here,” Hawk observes, “and I am here.” That’s why he’s the leader, I guess; nothing gets past the guy. And then we cut away. Well, that was a great scene.

A huge bonfire is lit by…somebody. I don’t know. We see Voltan by the fire, so maybe he’s…I don’t know. Then we cut back to the Convent. Well, that was a great scene. Seriously, did somebody misorder the reel changes or something?

So back to the Convent, where the Fellowship broods in stony anticipation. They say in war that the waiting is the most difficult part. Apparently that’s true for movie-watching, too. Suddenly, Crow’s head rears up, and he breaks the silence. “One man,” he reports, “on a horse.” It’s Voltan, approaching the Convent.

Voltan hails the Convent, and Sister Monica goes outside to parlay. Voltan tells her to have the gold ready by the following night—oh, brother, could you just get on with it already?—or else the Abbess will return to the Convent in a less than pristine condition. Sister Monica then returns to again castigate Hawk for not paying the ransom in the first place. Man, it’s hard to keep up with this movie, the way it keeps shooting off in all different directions.

Hawk again looks particularly pensive, and the camera glides in for a severe close-up. Then, just as I’m pleading “Oh, please, not another friggin’ flashback!” we get another friggin’ flashback. I mean, really, didn’t we sort of get the point from the previous three flashbacks? Guess not.

In this latest chapter in what threatens to become a never-ending series, Hawk is holding Eliane in his arms as she dies. The only real thing we learn from this is that these events take place not in the distant past, but apparently right before the movie started. (I’m not sure how Hawk healed from the crossbow bolt in his shoulder so quickly then, but there you go.) “Voltan goes to destroy your father,” Eliane gasps. Uhm, how the hell would she know that?

When Hawk finally stops daydreaming, his men ask for his instructions. “We are few,” Hawk notes. “Voltan has too many men.” Particularly if you count all the ones who stay off-camera. “If you’re being stung by wasps,” Gort replies, giving forth with a folksy metaphor, “you can either cover your head, or you can search out their nest and destroy them.” I don’t know if many people search out wasp nests while they are actually in the process of being stung by them, but then I’m not much for the folksy metaphors. Still, Hawk digs it. “Let us find ourselves a nest,” he agrees, “and bring the odds in our favor.”

Crow is sent off to fetch the Sorceress for her continued aid. For the love of Pete, would you guys just get on with it already?! Apparently not, because we then cut to Crow running through the forest in slow-motion. He was riding a horse earlier, so I’m not sure why he’d be on foot now, but then I’m not the Last of the Elves. At least they don’t drag this out, though, as Crow returns to the Convent with the Sorceress in about five seconds.

With the last piece (we hope) in place, we cut to the Fellowship surreptitiously spying upon Voltan’s camp. In an awesome special effect, Crow is seen to effortlessly jump high into a tree while his comrades stand stock still in the foreground. I don’t want to blow the Movie Magic here, but this cinematic wizardry was achieved by having the actor jump out of the tree and then processing the film backward. It’s amazing to think that such an eye-poppingly sophisticated effect could have been executed as early as 1980, isn’t it?

From his vantage point, easily four or five feet higher than Gort stands, Crow reports that the Abbess is not in apparent view. “I am ready,” the Sorceress exclaims, and then Magic Glowing Potatoes or something appear in her hands, and the dry ice machine goes positively berserk. The camp is soon covered with a dense fog, which not only aids the Fellowship’s cause, but helps to disguise the fact that Voltan has nowhere near as many men at his command as has been claimed throughout the picture.

The fog is so thick, in fact, that we can barely make out the action. (Not, however, that this prevents Crow and Ranulf from unerringly mowing down their barely seen opponents from a distance.) Even so, the Fellowship not only manage to slaughter a goodly portion of Voltan’s soldiers, but to kill most of the same ones a good half dozen times each. In fact, not only are the same guys presumably being slain numerous times, but I’d bet the same fellows had already been kacked several times earlier in the proceedings.

By the way, not to be a kibitzer, but wouldn’t the large glowing stone in Hawk’s sword be sort of disadvantageous when committing a commando raid in a thick fog? He sticks out like Rudolf the Red Nosed Reindeer.

In the end, the Fellowship massacres a significant number of Voltan’s weirdly multiplied forces. However, when Hawk enters Voltan’s tent, he finds his brother holding the Abbess at sword point. It’s a stalemate. Since the enemy’s *cough* still mighty (if conveniently unseen) numbers are starting to regroup, Ranulf grabs Hawk and drags him off. That’s right, we still haven’t gotten to the final showdown yet. Man, this is one sadistic frickin’ movie.

Back to the Convent. Good grief, Last Year at Marienbad moved faster than this. “He will be here soon enough,” Hawk mutters. “This is where the final struggle will be.” Yeah, promises, promises. Meanwhile, my final struggle involved trying to keep my eyes open for the film’s remaining twenty-one minutes. (This was a struggle I lost, by the way. With six minutes left of movie left, I turned in for the night, utterly exhausted.)

However, it appears that something audience-pleasing is finally going to happen. Since the film’s gone to some great effort to make Sister Monica an annoying retard, they finally make it clear they intend to kill her. She sneaks off to try to make peace with Voltan. She is shown into his tent, and conspires to betray Hawk if Voltan will spare the Abbess. Hmm, Sister Monica just went from annoying retard to the Greatest Movie Character Ever, at least assuming she can actually help get all the heroes killed. Now *that* would be an audience-pleasing ending. (OK, that’s not going to happen, but still, it’s a nice thought.)

Back to the Convent. You know, I’m really starting to hate typing that sentence. Since the film has so much time left to blow, Crow starts up with the melancholy philosophizing about being the last of his kind. Then Baldin announces that the doors are secure, and that it would take a “thousand men to get into here now.” Really? Man, that’s a well-fortified Convent. Also, since one of the two entrances is a nice large double-door secured solely with a two by four, I’m not sure Baldin’s engineering skills are really up to par.

Soon all the men are sleeping, save Gort, who is standing guard. Sister Monica slips him Ye Olde Mickey, and the trap is sprung. This is accomplished by her slipping the super-invulnerable two by four from its wall brackets. Truly this was otherwise an impregnable fortress.

Hawk wakes to find Voltan’s sword at this throat. Needless to say, Voltan wants Hawks’ death to be nice and slow, thus explaining why, as is always the case in these things, the villain doesn’t just kill his nemesis and get it over with. However, (SUPER TOP LEVEL SPOILER ALERT) Sister Monica then pays for her perfidy with her life. Frankly, it would have been far more cruel to let her live after telling her that he’d already slain the Abbess in some horrible fashion, but that sort of thinking is a bit too sophisticated for films like this.

Vowing that Hawk’s death will be slow and painful—much like this movie, really—Voltan commences with the Villain’s Rant, and Hawk with the Hero’s Retorts, and seriously, can we just move on here? It’s amazing how some films find it such a chore to fill a scant 90 minutes.

So Voltan calls for fire (although several of his men are already standing around with lit torches), the better to make Hawk suffer as he did. And then he ambles around the room, having sport with his brother’s comrades. I have to say, though, the film actually flirts with being entertaining here, because man, Palance just pulls out all the stops. It will take some mighty casks of mustard to adorn all the ham he’s serving.

Hawk is about to get a hot poker shoved into his face when Baldin announces that he knows where the ransom money is hidden. Voltan approaches, and the dwarf kicks him right in the still-unseen Skeletor half of his face. For this Baldin gets a dagger in his chest. However, that might have been his plan. I’d have been trying to get out of this movie, too.

Voltan runs off, hoping to alleviate his own agony while prolonging ours. Meanwhile, the men he leaves behind—somewhat less than a thousand, you may be sure—are quickly distracted by the urns of wines fetched in by the nuns. Then, seemingly seconds later, Voltan is seen in the Dark Wizard’s cave. Either the editing here is really bad—not exactly a shocking accusation, I’ll admit—or the Convent is but a couple of dozens yards away from the Wizard’s domicile.

I guess it’s the former, though, because when we return to the Convent, it seems like several hours must have passed. All of Voltan’s men are passed out drunk, except for one swaying, bleary-eyed sentry. (You wouldn’t think discipline would be so lax, considering that Voltan kills his men at the drop of a hat, but there you go.) This naturally allows Hawk and the others to scheme their escape.

Luckily, the Sorceress shows up in deus ex machina fashion, and removes the board barring the door by levitating it in a highly wobbly fashion on some highly mystical wires. This is a good thing, because our heroes are obviously too inept to have possibly escaped on their own.

The Sentry, rather than raising the alarm, just approaches the doorway to stare quizzically at the blow dart-like muzzle that peeks through the now open panels. This goes off with a gun-like report, but instead of a bullet, it cocoons him with—and I’m not kidding—several cans’ worth of Silly String. (!!!) Wow. It takes a lot of balls to call that a special effect, let me tell you.

We catch up with the Fellowship later, standing in the woods at the break of dawn. There they, and we, supposedly, will mourn the imminent death of the unconscious Baldin. (Yeah, right. For my part, I’m mourning the non-death of the rest of them.) Needless to say, even this happy occasion is ruined when Baldin rouses for a Final Goodbye. Great Jabootu, this film drags more than RuPaul. He gasps out a last, thankfully brief speech, which is accompanied by a syrupy violin. (!) Let no cliché be left unturned!

Leaving their comrade buried under a big soap bubble with glowing stuff in it, the remaining heroes plot their revenge. If we’re lucky this will only involve returning to the Convent maybe another half a dozen times, interspersed with several scenes of slow-motion horse riding through the woods.

Meanwhile, Voltan is threatening to kill all the nuns if Hawk isn’t in his hands by dawn. Since in the burial scene it was already daylight out, apparently he means dawn of the next day. Voltan is really responsible for how long all of this is taking, because he gives way too much time for people to obey his demands.

Then it’s back to the Fellowship in the woods. Seriously, this film is about 75% padding, and that might be a generous estimate. Again the Sorceress is used as a convenient plot crutch. “My magic powers will not harm you,” she whispers, “but just for a short while, my powders will create a whirlpool of flying firebolts to blind their eyes!” Their eyes?! Wow, those are the worst thing to blind!

Sure enough, she applies a generous amount of Whooshing Powder to their campfire, and the result is some of the most ridiculous animated ‘effects’ work I’ve ever seen. The ‘firebolts’ burst through the door of the Convent, and pelt Voltan’s men. If I had to guess, I’d say they fired several hundred ping-pong balls from an air cannon, and then painstakingly animated all of them with a greenish glow. I can’t even begin to describe how stupid this looks. Peewee’s Playhouse had better special effects than this, and that was a kid’s TV show made a mere half a dozen years later.

Then a huge, thick cloud of fake movie snow or some crap blows into the room. Using this as cover, Hawk and his men race into the room to kill this same crowd of extras another five or six times each. Note that the fake snowstorm serves the same purpose as the earlier dense fog, in purportedly disguising this fact from the audience.

The down side, naturally, is that we can barely make out what the hell is happening. Indeed, we only know that Voltan is (AGAIN!!!!) planning to escape with the Abbess because they dub Palance’s voice talking over a blurry blob shape that could really be just about anything. Meanwhile, one barely visible sequence involves a Miscellaneous Sister saving Gort by taking a knife in his stead, and then Voltan knocking out the giant as he mourns her death.

Then it’s outside, where it’s again foggy (!), and all sorts of highly annoying editing tricks are used to ‘hide’ the fact that Hawk is again killing some of the exact same ten guys for about the twentieth time. In the end, though, he saves the Abbess, as if anyone cared.

Then, with ‘all’ of his brother’s men finally dispatched, he reenters the now clear Convent for, FINALLY!!!, the Final Showdown. I almost weeped upon realizing that the movie might actually end someday. I was starting to regard the chances of it ever coming to a conclusion with the same lack of hope I have of ever seeing the Cubs in a World Series.

However, just to prove once more than nobody here knew what the hell they were doing, Hawk walks through the chamber to find the dead bodies of Crow and Ranulf. So the film spent all of this time introducing us to both of them, and trying to get us to ‘care’ about them, and then kills them both off-camera!! I mean, seriously, what the hell were they thinking?! I mean, yeah, it establishes Voltan as a bad-ass (sort of), but they could have done that even more effectively by showing him killing them. I seriously don’t know what to make of this.

ANY-HOO, Voltan still has some remaining Sisters and Gort left to threaten, and so he does. He commands Hawk to lay down his sword, and so Hawk does, because—and admittedly, many audience members may have forgotten this during the film’s interminable eight hour running time—he can call it to hand by thought alone. Gee, convenient that Voltan doesn’t know that, eh?

Even now, though, with only eight minutes of running time left, everybody moves like they were swimming in molasses. It’s like some demonic version of Speed where people are trapped in a movie that will explode if it moves at faster than one-quarter time.

Anyway, Hawk divests himself of his sword. Then, when Voltan bids him to pray to his god, he does. Because heaven forbid this movie should, even as it nears its end, actually get on with things. So Hawk kneels, and prays. Only this is a stratagem, it seems. For in doing he pulls out a heavy cross Eliane had given him. This (rather retardedly) turns out to have a little blade hidden in it, which he tosses across the room and impossibly uses to cleave the rope holding Gort.

Voltan seeks to strike, but pulls up in amazement when Hawk levitates the Mindsword into his hand. (He’s a bit of a show-off, really, because it was at his feet and he could have easily bent over and just picked it up.) Voltan then tries to trick him with one of his throwing knives—which again isn’t the sort of knife one could reasonably throw; it’s like they just didn’t care—but Hawk bats it aside with his sword.

Then, and I swear—in more ways than one, actually—the long-delayed swordfight begins (and proceeds throughout)…IN SLOW-MOTION!! For the love of Pete! It’s like the director was getting paid by the minute. And boy, nothing adds drama to a swordfight like slo-mo. The fact that this is accompanied by another of the film’s awful music cues doesn’t help any, either. I don’t want to surprise the hell out of you, but in the end Hawk stands triumphant.

As Voltan lies dying, his helmet finally falls off to reveal some not entirely interesting burn make-up, which they didn’t even care enough about to highlight with a close-up. And this wasn’t playing up his hideous disfigurement about twenty different times. “Brother,” Voltan gasps, “I shall wait for you at the Gates of Hell!” As The Film Began With Embarrassingly Generic Clichés, So Doth It End.

Next we see sole survivors Gort and Hawk preparing to leave the Convent. (Oh, yes, I’m sure this coda will prove entirely necessary and interesting.) The Abbess and the sisters bid them well. Then, in the currently empty Convent, we see a transparent overlay of the Dark Wizard entering the room.

In one of the most appalling displays I can honestly remember, he makes off with Voltan’s corpse, noting “Your sleep of death will not last long!” That’s right, after all this, they had the sheer, unmitigated balls to promise a sequel! And not only that, but they were going to bring Voltan back and basically start again from ground zero. Seriously, everybody connected with this film should be burned to ashes, and the soil on which they stand sewn with salt.

Ironically, however, while it is promised that Voltan’s death will not last long, the movie still won’t frigging end. Sure enough, we cut to Hawk and Gort meeting with the High Abbot, to whom they have given the gold. Then they are in the woods, bidding each other farewell. First, though, the Sorceress issues a warning about the Forces of Evil gathering to the south. And so, with a quip (sort of) on their lips, Gort and Hawk turn their horses in that direction. “We shall meet again!” the Sorceress cries as they ride off. Thankfully, though, that is one evil prophecy that has yet to come true.

And, cue badly animated hawk again, and…FREEDOM!!!!!!!

Afterthoughts:

First, let’s give Hawk the Slayer points for being ahead of the curve. The big boom in ’80s sword and sorcery films came two years after its release when 1982’s Conan the Barbarian was released. This resulted in a predictable wave of generally lousy low-budget fantasy knock-offs, including The Beastmaster, Deathstalker, Barbarian Queen, The Adventures of Hercules, Hundra, Krull, The Sword and the Sorcerer, Ator the Fighting Eagle, and quite a few others. The big difference between today’s world and that one? You could have seen all those movies in theaters. Sigh.

So Hawk was, at least, a bit of a trendsetter. It obviously was hoping to cash in on a perceived market for ‘old-fashioned’ entertainment fueled by the massive success of Star Wars. (Certainly Voltan, with his bell-shaped, face-covering helmet, seems a nod to Darth Vader, not to mention the ‘magic’ swords.) Even so, it got to this variant well before the competition, so good on them. The film also references (if none too well) Tolkien in assembling a fellowship including elves and dwarves. In fact, they even *cough* go Tolkien one better by including a ‘giant’ in the mix.

Sadly, it also introduces several tropes that were to become all too familiar in the deluge of fantasy dreck to follow: the way the film goes off-point during its entire middle section, the repetition of those scenes, horrible comic relief, the over reliance on slow-motion shots, goofy ‘magical’ weapons, the ill thought-out use of magic in general, the silly beasties (although there’s only a small bit of this here), and a tonality problem perhaps best typified by the wildly varying acting styles on display Most obviously, the wooden acting of John Terry (Hawk) and the scenery-chewing antics of Jack Palance contrast wildly, albeit in diametrically different ways, with the solid, understated acting provided by the array of seasoned character actors.

This manages to undermine the proficiency of the supporting cast, which is too bad, because by all measures this should be much more of a strength then it ends up being. Another problem in this regard is that the episodic nature of the film, presumably meant to lend the film as much of an ‘epic’ feel as a low production budget would allow, means that this surfeit of fine actors are individually given little to do. Only William Morgan Sheppard as Ranulf has enough screen time to really flesh his character out at all, and since he often shares the screen with Terry, he serves mostly to emphasize the lead actor’s thespian limitations.

So again, you admire the impulse to hire a raft of familiar veteran actors (Sheppard, Patrick Magee, Patricia Quinn, Harry Andrews, Roy Kinnear, Ferdy Mayne, Graham Stark, Christopher Benjamin, etc.) to appear in the various vignettes. However, since they are generally onscreen for but a minute or two, you have to wonder if there was really any point to it. It obviously doesn’t make things worse, but it doesn’t lend the film nearly as much advantage as you’d instinctively believe.

Hawk avoids the camp approach found in The Sword and the Sorcerer and The Barbarian Brothers, but features just enough of it to again toss off-balance the generally too-serious tone found in the bulk of the film. In particular, the attempt to ape Spaghetti Westerns for many of the numerous “showdowns” fails signally. Even Sam Raimi couldn’t quite pull this off in The Quick and the Dead, so you can imagine how successful it is here.

This was the first film for director Terry Marcel, who also co-wrote the picture. (Actually, the amazing thing is that it wasn’t his last picture.) He who went on to work mostly in British television, which isn’t much surprise.

He played off his experience with this film in future projects like the telepicture Prisoners of the Lost Universe (1983), a sword and sorcery TV movie; episodes of something called The New Adventures of Robin Hood; and a more recent (2000) attempt at a Xena-type adventure show called Dark Knight. Prisoner of the Lost Universe even employed the actors who played Baldin and Crow.

Joining Marcel on the writing chores was film veteran Harry Robertson. The two apparently enjoyed working well together, as they also teamed up on in various capacities on later Marcel pictures like Prisoners of the Lost Universe and the camp adventure flick Jane and the Lost City.

However, although he on occasion worked as a writer (as here) and producer (here also), Mr. Robertson was primarily a composer. He indeed provided this film’s music, which as I’ve noted I’m not overmuch a fan of. However, he also scored such pictures as The Oblong Box (1969); The Vampire Lovers (1970); Fright (1971); Lust for a Vampire (1971), Twins of Evil (1971), Countess Dracula (1971), Demons of the Mind (1972), Legend of the Werewolf (1975), The Ghoul (1975) and a host of non-genre films. Meanwhile, his most Jabootu worthy credit is that he was the music arranger on the legendary 1969 turkey Can Hieronymus Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humppe and Find True Happiness?

I’m not going to go into the careers of all the actors, because so many of them have so many credits it would take forever. Obviously one of these is Jack Palance, who certainly needs no introduction here, but also the array of character actors mentioned above.

John Terry, with the lead in the picture being basically his first acting gig, nonetheless went on to a successful career. Notable roles include that of Lt. Lockhart in Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket; his appearance as one of a zillion Felix Leiters, in the James Bond entry The Living Daylights; and recurring roles on programs like E.R. and 24. However, his real claim to pop culture immortality is his occasional role as Dr. Christian Shephard, the father of the main character on Lost.

Bernard Bresslaw (Gort) parlayed his size into a solid career. Fittingly, he appeared early on in a couple of Robin Hood projects, played a comical Jekyll & Hyde analogue in 1959’s The Ugly Duckling (opposite Jon Pertwee, no less), and appeared in such genre films as Blood of the Vampire (1958), Carry on Screaming! (one of a zillion ‘Carry On’ films he did), Moon Zero Two, Old Dracula (with David Niven), and even Krull. He also appeared in a Doctor Who serial (Troughton’s, not Pertwee’s), and the Loch Ness Monster episode of The Goodies.

Shane Briant notably played the bored aristocratic son in the superior Hammer flick Captain Kronos – Vampire Hunter, where his languid performance indicates that his overacting here was perhaps at the behest of the director. Mr. Briant appeared in Demons of the Mind (1972), played the titular role in a 1973 telepic version of The Portrait of Dorian Gray, Hammer’s Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974); and has since remained busy playing a wide variety of movie and TV parts.

Catriona MacColl (Eliane, Hawk’s lost love) is most famous for starring in a trio of Lucio Fulci’s most famous films; City of the Living Dead, The Beyond and The House by the Cemetery. She also appeared in an episode of The Hitchhiker, and continues to work in French TV.

Other than that, almost everyone has a billion credits, and you’ll have to investigate them yourselves.

By the way, I guess I should always check YouTube these days. Many of the film’s ‘special effects’ scenes can be found there, as well as this “making of” documentary (!).